Rec Sports

Edward Anthony Marn – The Dominion Post

Edward Anthony Marn, 93, passed away peacefully on Monday, December 1, 2025, at Madison Rehab and Nursing Home, in Morgantown.

Born on December 26, 1931, in Lansing, Ohio, Edward’s life was marked by dedication to his family, his community, and his country.

As a young man, Ed served with honor in the United States Air Force. His patriotic service was a point of great pride and set the foundation for his lifelong commitments to both leadership and mentorship.

After his military service, he embarked on a distinguished career in banking and became a well-respected figure during his 17-year tenure as President of the New Martinsville Bank, as well as an executive at Ormet Credit Union until his retirement. His professional integrity and approachable leadership style left a long-lasting imprint on the industry and those who worked alongside him.

Ed met the love of his life, Helen Hundley, at Keesler Air Force Base and they shared a blissful marriage of 71 years. The legacy of their enduring partnership includes children: Cindy Marn of Westover, Karen Biggs (Jimmy) of Aberdeen, Md., Michael Marn (Patty) of Red Lion, Pa., Mary Eberhardt (Keith Bayles) of Uniontown, Pa., and Beth Monroe (Terry) of Alma. He also has seven grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

A devout Catholic, Ed was an active member of Mater Dolorosa Roman Catholic Church in Paden City, where he served as a Minister of the Eucharist and shared his faith as a teacher of CCD and Acolytes for many years. Later, he continued his worship at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Star City. His faith was a cornerstone of his life, guiding him through both trials and celebrations.

Beyond his professional and spiritual contributions, Ed had a vivacious passion for life and culture. He was an avid golfer and fisherman, a devoted Mountaineers fan, and enjoyed following Ohio State, Duke and Notre Dame in various sports.

Ed was also a gifted storyteller, with many enthralled by his knowledge of history, especially military history. His voice was one of harmony, not only in life but literally as a member of his Barbershop Quartet, “The Mason Dixonaires.”

His philanthropic spirit was evident in his contribution to youth sports, where he coached softball for his daughters. He believed in nurturing the potential of the young and was a positive influence on many young lives.

Ed was preceded in death by his parents, Anthony Sylvester Marn and Mary Zoladz Marn; as well as his brother, Anthony “Babe” Marn.

Friends may gather at Mater Dolorosa Roman Catholic Church in Paden City, from 3 to 4 p.m., the time of a Mass of Celebration, on Friday, December 26, with Father Joseph Abraham as celebrant.

McCulla Funeral Home is in charge of arrangements and online condolences may be sent to the family at www.McCulla.com

Rec Sports

Michigan parent files Title IX complaint with allegations over transgender athlete playing in volleyball game

A southeast Michigan parent has filed a Title IX complaint with the U.S. Department of Education over claims a transgender student athlete played against his daughter’s volleyball team.

The complaint alleges the opposing school didn’t submit the proper waiver for the child to play, that parents didn’t get notice ahead of the match, and that both teams shared a locker room while playing in Monroe.

Monroe High School student Briley Lechner plays on the volleyball team. She said her team was caught off guard by the player.

“Nobody would have expected that. That would’ve been the last thought because as I was looking at this person, admiring how amazing they were, admiring how high they could jump, I was kind of getting down on myself. Like, I wonder why I’m not capable of that,” Lechner said during a press conference to announce the complaint in Monroe Monday.

The Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA) says it received one waiver for a transgender child to play sports this past fall but that it couldn’t give more information for privacy reasons.

MHSAA spokesperson Geoff Kimmerly said those waivers are granted on a case-by-case basis, using factors like medical records and whether the student has gone through hormone therapy or gender-affirming surgery.

“We look at every athlete individually,” Kimmerly said. “We’re talking about one individual student, so they’re all going to be different a little bit in some way and so they’re all going to be unique.”

Kimmerly said that’s been the practice for several years. Sometimes sports seasons don’t get any requests for transgender students to play.

The stated goal of the Title IX complaint is to stop all transgender kids from competing in girls’ sports.

Sean Lechner, Briley’s father, said he believed a student assigned male at birth would always have a competitive edge when competing against athletes assigned female at birth.

“It’s not fair, it’s not equal, and it’s not right. It takes every bit of dignity and privacy away from our girls,” Sean Lechner said.

Michigan civil rights law bans discrimination based on gender identity. But, in February, President Donald Trump issued a federal executive order banning trans athletes from girls’ sports.

Kimmerly said the MHSAA, a private non-profit that coordinates Michigan’s school sports, needs state lawmakers to give it more guidance about what to do with the conflicting policies.

“We know that they recognize these issues. We have reinforced over and over again that we have to follow the law. And when there are conflicts in the law, we rely on the Legislature and the courts to provide clarity,” Kimmerly said.

Several Republican state lawmakers and candidates for state and federal office attended Monday’s press conference.

In May, the Republican-led state House of Representatives passed bills to exempt school sports from that anti-gender identity discrimination law.

Package co-sponsor State Representative Rylee Linting (R-Grosse Ile Twp) said the new complaint was about keeping student athletes safe.

“To be clear, this is not about singling out a particular student, this is about calling out the individuals that are allowing this to happen,” Linting said.

The bills have stalled in the Democratic-led state Senate where they’re not likely to see any movement.

Meanwhile, LGBTQ rights advocates say transgender children should have equal chances to play youth sports. They argue zeroing in on one students’ case takes away from their teams’ accomplishments and makes them a target for adults to harass and bully them both online and in person.

The U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear arguments over whether trans athletes should be allowed to play in girls’ and women’s sports next year.

Rec Sports

Improving on-field decision making using video-based training – A pilot study with young volleyball players

Abstract

Decision making is a crucial skill in several sports, which researchers and practitioners have for a long time sought to improve. Recent studies have focused on the potential of video-based training, but most examined adult athletes and did not typically measure transfer to on-field performance. Therefore, we investigated the effect of a 4-week video-based training on youth volleyball players’ on-field decision making. Twenty female volleyball players between 13 and 15 years old were initially assigned to either an experimental or control group, of whom 16 (eight per group) completed the entire study. Decision making skill was assessed on a video-based task, as well as an on-field task. The results of our pilot study demonstrated that only the experimental group significantly improved their decision making skills on both the video-based assessment and on-field test (motor decision) between baseline and retention. This pilot study indicates that video-based training can be an effective way to improve young players’ on-field decision making skills, although improvements in motor execution may require intermittent physical practice.

Citation: De Waelle S, Bennett SJ, Scott MA, Lenoir M, Deconinck FJA (2025) Improving on-field decision making using video-based training – A pilot study with young volleyball players. PLoS One 20(12):

e0338523.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0338523

Editor: Gustavo De Conti Teixeira Costa, Universidade Federal de Goias, BRAZIL

Received: April 4, 2025; Accepted: November 24, 2025; Published: December 9, 2025

Copyright: © 2025 De Waelle et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

To make appropriate decisions in team sports such as soccer, volleyball or basketball, it is necessary to process and monitor multiple sources of information from opponents, teammates and the ball [1]. Expert athletes in these sports exhibit superior decision making skills than sub-elite athletes or novices [2,3]. This expert advantage is even present in young athletes (i.e., during adolescence), with high-level soccer players outperforming lower-level athletes on decision making skills [4]. The implication is that decision making is already an important aspect of expertise in young athletes, and that its development at this crucial period for talent identification warrants consideration [5,6].

On-field decision making in team sports can be trained by manipulating task constraints that influence the number or nature of decisions to be made [7,8]. This is often done by means of small-sided games, which usually involve fewer opponents and a smaller pitch size in order to reduce the number of decision making options. Despite the success of this on-field training method, it is not simple and/or efficient to implement, and is not individualized. Therefore, researchers have considered how to improve decision making through off-field training [9], such as watching sport-specific videos outside of their regular practice sessions. Typically, this would involve watching an unfolding sequence of play, with the video being stopped at a key point of interest (e.g., ball-foot contact in soccer), after which the participant is required to select the best possible decision (e.g., where to pass the ball) by means of a button press, verbal report or the appropriate sport-specific movement [10].

In sports such as softball [11], cricket [12] and basketball [13], most studies have shown task-specific improvements in adult participants decision making after sports-specific video-based training. However, the extent to which the positive effects of off-field, video-based training transfer to on-field performance remains unclear [14], in part because transfer is rarely measured [15,16]. Of the few studies that did examine transfer, the evidence is equivocal [12,13,17,18]. For example, Gorman and Farrow [18] found that a four-week, video-based training intervention in basketball improved decision making of all groups of adult participants (including the control and placebo group) on the video-based test, but not in on-field, match situations. Conversely, Pagé and colleagues [13] reported transfer of video-based training effects to on-field decision making in basketball, but only when the on-field situations matched those presented during the training (near transfer). Moreover, when practice occurred in virtual reality using a head mounted display instead of 2D videos displayed on a computer monitor, the training effect was extended to untrained situations (far transfer).

With youth athletes there are a similarly small number of studies that have investigated the effect of video-based training on decision making skills [17]. As with the adult studies, findings are mixed and little consideration is given to on-field transfer. Nimmerichter and colleagues [14] reported that 6 weeks of video-based training improved the video-based decision making skills of 14-year-old soccer players, but transfer to on-field performance was not measured. Panchuk and colleagues [18] found that 17-year-old female basketball players (n = 6) significantly improved their decision making following 3-weeks of immersive training on a video-based decision making test, but only to a similar extent as the control group (n = 3) (15). The male counterparts showed no improvements in video-based decision making irrespective of whether they took part in the intervention (n = 5) or control protocol (n = 4). No significant improvements were found in on-field performance for either group. More positive effects initially seem apparent in a recent meta-analysis on the effectiveness of decision making training in volleyball players [19]. However, closer inspection of the six original articles that studied youth players indicates that only four used off-field video-based training, and that of those only one found a 20% positive transfer to on-field performance [20].

At present, therefore, despite there being some evidence that video-based training can be a useful tool for the improvement of video-based decision making abilities, the extent of transfer to on-field performance remains unclear, particularly in youth athletes. The current pilot study aims to explore the effects of a four-week, video-based decision making intervention on on-field performance in youth female volleyball players. As commented above, decision making in volleyball requires the athlete to process and monitor multiple sources of information from opponents, teammates and the ball. The constant movement of the ball (i.e., it is not allowed to be caught and held) and the speed at which it travels (e.g., in excess of 100 km/h), combined with the dynamic player positioning, means that quick, accurate decisions on where and how to spike the ball are essential to capitalize on scoring opportunities. Simple and efficient training methods that improve decision making of youth athletes could have meaningful impact on their enjoyment and progression, as well as match outcome. To assess learning and transfer in these athletes, baseline and retention tests on video-based and on-field decision making tasks in volleyball were performed either side of the training phase. To permit a comprehensive analysis of on-field decision making [21], three measures were included: verbal decision, motor decision and motor execution. The general hypothesis was that the experimental group would improve their decision making performance on both the video-based task and on-field decision making task, while we expected no improvements in the control group on either task.

Materials and methods

Participants

Assuming an effect size of Cohen’s f = 0.25 (ηp² = 0.059), a power of 0.8 and a correlation between repeated measurements of 0.25, it was determined that a total sample of N = 50 would be required for the interaction effect of our mixed design ANOVA (G*Power 3.1). Despite only being able to recruit 20 participants, it was decided to proceed with this sample on the basis that the initial effect size estimation could have been too conservative compared to previous similar work [12,13,18], and that any findings could still contribute to subsequent meta-analysis.

The recruitment period started on 03/08/2020 and ended on 25/09/2020. Participants of the under 15 age category were recruited from four different teams within three Flemish youth volleyball clubs and were either assigned to the control group that would be receiving the placebo training (n = 9), or the experimental group that would be receiving the decision making training (n = 11). To limit baseline difference between groups, the selected volleyball teams were all playing at the same competition level. Participants were unaware of the fact that there were two different groups, and were randomly assigned to the experimental or control group per team. Prior to the study, participants and their parents provided written informed consent and were made aware of the fact that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ghent University Hospital ethics committee (registration number: B670201836811).

Procedure

Participants completed baseline assessments of video-based and on-field decision making skill, followed by a 4-week intervention involving different types of video-based training. The initial study design included measurements of both the video-based and on-field tests immediately following the intervention. However, it was only possible to administer the video-based test at the participant’s home without the supervision of a trained researcher (NB. These data are not reported). Between 28 and 31 days after the intervention ended, participants completed retention assessments of both the video-based and the on-field tests. Neither of the groups took part in any on-field practice during the study.

Measurements

Video-based test.

The video-based decision making task was based on the decision making task developed by De Waelle and colleagues [4] and validated for use in youth volleyball players. In this task, players viewed a series of 38 video clips of a progressing offensive sequence that was occluded 66ms before ball contact by the spiker. Participants were asked to imagine themselves as the spiker, and to decide on the most optimal zone to play the ball (i.e., with the highest chance of scoring a point). They then indicated their decision by pressing the corresponding key on a keyboard as fast as possible. To ensure face validity of the task, the video scenarios were developed in close collaboration with three certified volleyball coaches. The test included four different viewing conditions with 2, 3, 4 and 6 opponents, thereby reflecting realistic volleyball training and match situations. For the first two conditions, with 2 and 3 opponents, participants could choose between 6 zones, while for the last two conditions (with 4 and 6 opponents), there were 9 zones to choose from. The inclusion of more players resulted in progressively more complex conditions requiring a larger field size and more zones. This also ensured that zone size was similar across all conditions. The number of opponents, the size of the field, the number of zones and the number of clips per condition are displayed in Table 1. Each video clip lasted about 5 seconds, after which participants had 5 seconds to execute their response. However, participants did not have to wait until the screen was occluded to make their decision. A screenshot of exemplar video clips is presented in Fig 1, and a schematic of the test setting is shown in Fig 2.

The test took place in a separate and quiet room, with only the participant and the experimenter present. The video clips were projected on a 1.07m (w) x 0.6m (l) projection screen using an LED HD video projector (LG PH550G, Seoul, South Korea) that was placed on a table 1.50m from the screen. Subjects were instructed to stand behind this table at 2.00m from the screen. Video clips were displayed with OpenSesame software [22], which was also used to record the responses using a regular USB-connected keyboard.

At the start of the decision making test, participants received detailed instruction, as well as an example and two practice trials. All participants completed the different viewing conditions in the same order, and within each condition trials were randomized for each participant separately. For each new viewing condition, a familiarization clip was shown, as the number of players and size of the court would change. The decision making test lasted about 10 minutes.

On-field test.

A series of simulated offensive sequences using actual players that represented the video-based test was used for the on-field decision making test, but only with six opponents as this relates closely to the actual game setting. Eight experienced volleyball players were recruited as ‘actors’ to play the roles of the six defenders on the defensive side, as well as the libero (who plays the ball towards the setter) and setter (who passes the ball to the participant) on the side of the participant. This did not reproduce exactly the video-based test but it did ensure that the participants received high-quality passes that provided them with optimal scoring conditions in terms of time and space. Before the test, the six defenders were given explanations and time to practice the different defence patterns they would have to execute. These defence patterns were the same as in the video-based test, and prior to each trial, one of the researchers would indicate through a sign which defence pattern was to be executed. The defence patterns were presented in a random order that was the same for all participants. The field of the defenders was divided in 9 zones using orange tape and zones were marked with colours to facilitate the participant’s verbal response. The net was a regulation height of 2.24m and the ball was a Mikasa V020W size 5. A schematic is provided in Fig 3.

Prior to the test the participant was given time 15 minutes to warm-up, including light jogging, dynamic stretches and volleyball-specific passing and attacking drills. Each trial of the test started with a free ball tossed to the libero on the participant’s side. The libero would then play the ball to the setter, who would pass the ball to the participant acting as the spiker. The participant was instructed to play the ball where they were most likely to score on the opposing side of the field, using any technique. They were also asked to call out the zone where they intended to play the ball (i.e., verbal reports). This was done because participants between 13 and 15 years old are not always technically skilled enough to play the ball where they actually intend to play, and thus verbal reports provide information on intended behaviour. If the defenders were able to defend the ball, they played a free-ball back to the libero on the participant’s side to start a new trial. If the ball was not defended, a new trial was started by a free-ball toss to the libero. Verbal reports were noted on paper by one of the researchers at the time of testing, and two cameras (see Fig 3) recorded the test from different angles to allow for analyses of (1) each decision, based on the landing location of the ball as well as the execution of the action, and (2) the correctness of the actors’ defence positions. Participants completed 20 trials as the left wing spiker and 20 trials as the right wing spiker. Rest periods between trials were not included, other than the time it took to prepare for the next trial, which reflects an actual game situation. The entire on-field test lasted 15–20 minutes, and there were no obvious signs or reports of fatigue from the participants. While a participant was actively performing the on-field task, no other participant were present.

Intervention

Both groups received 4 weeks of video-based training, with 4 sessions of 15 minutes per week, resulting in a total of 16 training sessions. The training sessions were conducted at home using the OpenSesame software, and commenced during the first week of the 2020–2021 season. Participants received a detailed manual before the study and were contacted by one of the research team to check that the software had been correctly installed and that they understood when and how to use it. Participants were instructed to spread out their training sessions over the week, and to not perform two sessions during the same day. This was checked in the log-files created by the OpenSesame software, which the participant sent by email to the research team after each training session. The log-files contained information about the participants’ responses and response times during training, as well as when they executed each session. While it is feasible that someone other than the participant could have completed the training, it is highly unlikely given that they would need access to the participants computer and email.

Experimental group.

The experimental group received training sessions that were highly similar to the video-based test, with the same instructions and manner of response. However, training sessions became gradually more difficult, starting with 2 opponents in the first week, 3 and 4 opponents in the second week, and ending with 6 opponents during the last two weeks. At the beginning of each training session, detailed instruction was given about which areas of the display players should pay attention to in order to make optimal decisions. Different topics were addressed within each of the difficulty levels. For example, it was explained that the role of the setter is to pass the ball to the left wing or the right wing spiker to ensure they have the time and space to score a point, and that the defending team will try to block the ball played by the spiker, usually with two players at the net in a position relative to each other that limits the zones available to the spiker that are not covered by remaining four defenders. It was also clarified what to do when receiving a pass that is difficult for the spiker to reach, or does not provide optimal scoring conditions. In this way, the intervention aimed to improve the participants’ decision making in standard, but also in non-standard situations (e.g., when you get a bad pass, or when the block has not formed correctly). Per training session, each participant completed 20 trials, i.e., 20 different video clips of 20 different volleyball scenarios. They were provided with feedback after each trial about the outcome of their response.

Control group.

The structure of the placebo training was similar to the experimental group, as they too completed 16 sessions (4 weeks x 4 sessions/week) that included detailed instructions followed by video clips to which they had to respond using the keyboard. The clips and responses were designed such that participants engaged in game settings. In the first two weeks, participants had to judge the quality of the first ball reception as quickly as possible, and in the third week, they had to judge the quality of the pass given by the setter. In the last week, they had to predict the direction of set-up. Accordingly, these tasks required participants to focus on the ball’s flight path, and not the positioning of blockers and defenders, which is considered critical for offensive decision making. As the control group did not receive feedback between trials, they completed 30 trials each training session to ensure they spent a similar amount of time performing the training task.

Dependent variables

Video-based decision making.

Prior to the study, a panel of three expert coaches viewed the video clips for the decision making test and selected the most optimal zone (i.e., the zone with the highest scoring probability, based on the position of the block and the defenders). Only the clips for which all three experts agreed were included in the test. Each participant’s performance on the video-based decision making task was assessed using the percentage accuracy of the 6×6 condition (i.e., percentage of times the optimal zone was selected). The 6×6 condition was chosen because this relates most closely to the on-field test and to the actual game that is played by this age group.

On-field performance.

This was assessed using 3 separate measures. First, the on-field verbal decision, i.e., where participants said they were going to play, was registered. Second, the on-field motor decision was recorded, i.e., where participants intended to play the ball, regardless of the quality of their execution and final ball landing location [21]. To this end, two experienced volleyball coaches analysed the direction in which the ball was played, in combination with the technique used, to decide on the player’s intended action. Interrater reliability of this judgement was examined by having 2 coaches evaluate all trials (n = 40) from 4 participants (2 from each group). This analysis indicated excellent agreement (Cohen’s unweighted kappa = 0.814). Finally, the on-field motor execution, i.e. what participants ended up doing, for which actual ball landing location was analysed from the video footage from the on-field test. For each of the three measurements, percentage accuracy was calculated per participant for the baseline and retention test.

Data analysis

Of the initial 20 participants, three from the experimental group dropped out during the study as they found it too time-consuming. In addition, one participant from the control group was unable to complete the retention test. Therefore, for both the video-based tests and on-field tests, we had complete data sets (baseline and retention) for 8 participants in each group (see Table 2).

To assess whether the intervention influenced learning of the video-based decision making task, the percentage accuracy scores were submitted to a mixed ANOVA, with group as the between-subjects factor and phase as the within-subjects factor (baseline, retention). To assess learning of the on-field task, the three dependent measures (verbal decision, motor decision and motor execution) were submitted to a mixed MANOVA, followed by mixed ANOVA, with group as the between-subjects factor and phase (baseline, retention) as the within-subjects factor. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were confirmed using QQ plots and Levene’s test. Significant interaction effects were further analysed using pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means with Bonferroni correction. The alpha level was set to 0.05 and partial eta square effect sizes are reported. Statistical tests were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0.

Results

Video-based decision making task

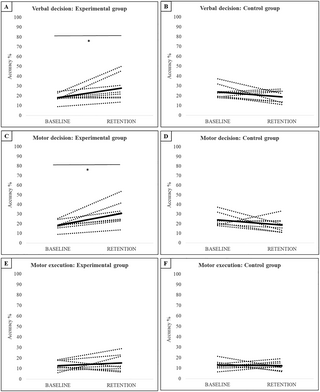

Mixed ANOVA indicated a main effect for phase, F(1,14) = 10.93, p = 0.005, ηp² = 0.44, as well as a significant phase x group interaction, F(1, 14) = 9.43, p = 0.008, ηp² = 0.40. There was no significant main effect of group, F(1, 14) = 0.69, p = 0.42, ηp² = 0.05. While performance of the control group did not differ between baseline and retention (Fig 4B), there was a significant improvement (p = 0.003) exhibited by the experimental group (Fig 4A). Importantly, no between-group differences were apparent at baseline.

Fig 4. Accuracy scores for the video-based decision making (6×6 condition).

Dotted lines represent individual results, the black line represents the group mean. *significant difference in the group mean, p < 0.05.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0338523.g004

On-field task

Mixed MANOVA revealed no significant multivariate main effect for phase, F(3, 12) = 1.29, p = 0.332, ηp² = 0.22, or group, F(3, 12) = 1.89, p = 0.185, ηp² = 0.32, but there was a significant multivariate phase x group interaction, F(3, 12) = 4.65, p = 0.022, ηp² = 0.54. Univariate tests also indicated no significant main effect for phase or group for any of the dependent variables. However, there was a significant phase x group interaction for verbal decision, F(1, 14) = 9.19, p = 0.009, ηp² = 0.40, and motor decision, F(1, 14) = 13.39, p = 0.003, ηp² = 0.49, but not for motor execution, F(1, 14) = 0.631, p = 0.44, ηp² = 0.04. There was no difference between the groups at baseline or retention for any of the dependent measures. However, the experimental group did significantly improve their motor decisions (Fig 5C, p = 0.017), but not their verbal (Fig 5A, p = 0.085) and motor execution (Fig 5E p = 1.00), between baseline and retention. The control group did not show any improvement in their verbal decision (Fig 5B), motor decision (Fig 5D), or motor execution (Fig 5F), with negative group mean differences between baseline and retention for each measure.

Fig 5. Accuracy scores for the on-field decision making variables.

Dotted lines represent individual results, the black line represents the group mean. *significant difference in the group mean, p < 0.05.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0338523.g005

Discussion

This pilot study investigated the effect of a 4-week video-based training intervention on the decision making skills of youth volleyball players. Consistent with the general hypothesis, only the experimental group exhibited improved decision making in the video-based task, as well as the controlled and representative on-field task (motor decision only). This latter finding is in line with some previous studies [13], and suggests that video-based training can indeed be useful to improve decision making skills in youth team sports athletes. Contrasting effects have been reported [18,23] but there are notable differences in the methodologies. For example, the aforementioned studies measured on-field decision making in small-sided games or actual match performance (far transfer), whereas both the current study and Pagé et al. [13] used a controlled, on-field test designed specifically to replicate the situations of the video-based test (near transfer). In addition, we found evidence for improved on-field decision making skills when video-based training employed a first-person perspective and provided feedback after each trial (see also [13]), implying that these may be crucial elements for a successful video-based training intervention.

Although there was a significant interaction for verbal decision making in the on-field task, there was no improvement by the experimental group after Bonferroni correction for multiple pairwise comparisons. Verbalizing a motor plan is a common approach in perceptual-cognitive research, but is a somewhat artificial task that is rarely practiced in an on-field setting. This could have posed an additional challenge for the youth volleyball players in the current study, thereby limiting their improvement. Observation of the individual data (Fig 5A) shows that while none of the participants in the experimental group exhibited a decrease in verbal decision making accuracy from baseline to retention, 2 participants exhibited less than 1% change. The lack of improvement by the experimental group in on-field motor execution was more robust, with no significant main or interaction effects. Observation of the individual data (Fig 5E) shows that 3 of 8 participants in the experimental group exhibited a decrease between baseline and retention. This finding is partly consistent with a recent systematic review that showed programs designed to train decision making usually only benefit perceptual-cognitive measures, and not perceptual-motor measures [17]. This could simply be due to the fact that perception and action are uncoupled in video-based training, with no or a non-representative motor execution required when responding to the video clips. However, the lack of perception-action coupling in the current study did not prevent participants from improving on the motor decision task, indicating that they were better able to correctly identify where and how to respond following the intervention. An alternative interpretation could be that not having the opportunity to physically practice the motor task, such as during 2 months of the current intervention, prevented participants from applying what they learned during the video-based training. Similar effects are found in work on voluntary imitation, with observational practice alone being less beneficial to subsequent motor execution compared to observational practice interspersed with physical practice [24,25]. As is the case for observational practice [26], it is possible that video-based training enables participants to perceive and represent relevant information, but it does not engage feedforward and feedback processes that are critical for skilled motor execution. The implication for future studies on decision making in sport is that video-based training should be combined with physical training, although the frequency and volume of each type of training remains to be determined. That said, if an individual is unable to take part in on-field practice sessions, video-based training can provide a valuable alternative by which decision making skills, and in particular motor decision making, can still be improved. Indeed, when looking at the individual data (Fig 5C and 5D), it can be seen that the majority of participants in the control group showed a decline or no change in performance, whereas all participants in the experimental group showed an increase in performance. This implies that video-based training might also be important in avoiding performance decline when athletes cannot physically train, for example when they are injured [27].

While this pilot study provides valuable insights into the use of individualized video-based training, it is important to acknowledge that there are some limitations. As noted in the methods, we initially planned to recruit 50 participants, but were only able to recruit 20 participants, of whom 4 did not complete the retention test, leaving us with 8 participants per group. Although this meant a reduction in power to detect smaller and moderate effects, a post-hoc sensitivity analysis indicated that this sample size was sufficient to detect an effect size of at least ηp² = 0.175 with a power of 80%. Notably, the effect size of ηp² = 0.04 found for motor execution was lower than both the a-priori and post-hoc critical thresholds, thus indicating that the finding of no significant improvement in this dependent measure by the experimental group was not due to insufficient power. As with some previous studies [20,28], the small sample size not only highlights the difficulty recruiting participants for training studies involving several sessions over several weeks (16 in total) followed by a delayed-retention, in which there are measures of off-field and on-field performance, but also raises a question about generalizability of the findings and the need for a replication study with a larger sample. Ideally, this would include a longer term follow-up to determine if there is any consolidation of the learning effects having resumed typical practice procedures. It could also be interesting to include more sequences of offensive play to better reflect the dynamic complexity of real competitions, and to determine transfer to the field in actual volleyball matches. Indeed, our use of simulated 6×6 offensive sequences with actual players in the on-field test was intended to closely reproduce the video-based test, and as such did not allow us to determine transfer to novel attacking sequences. Conducting such a study would benefit from collaboration with coaches of larger teams, allowing decision-making training to be integrated into regular practice activities, while also reducing the risk of participant drop-out.

In conclusion, this pilot study provides preliminary support for the effectiveness of video-based training for improving and retaining on-field motor decision making in youth volleyball players. Although the quality of motor execution did not improve, we suggest that this could be overcome by providing intermittent on-field training. Video-based training is easily accessible and low cost compared to virtual reality training, and could thus be an effective tool to maintain or improve the decision making abilities of youth players from grassroots to club level.

References

- 1.

Davids K, Savelsbergh GJP, Bennett SJ, Va der Kamp J. Interceptive actions in sport: information and movement. London: Routledge; 2002. - 2.

Bar-Eli M, Plessner H, Raab M. Judgement, decision-making and success in sport. Hoboken, New Jersey, US: John Wiley and Sons; 2011. - 3.

Williams AM, Jackson RC. Anticipation in sport: fifty years on, what have we learned and what research still needs to be undertaken? Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;42:16–24. - 4.

De Waelle S, Warlop G, Lenoir M, Bennett SJ, Deconinck FJA, Waelle SD. The development of perceptual-cognitive skills in youth volleyball players. J Sports Sci. 2021:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1907903 - 5.

Bennett KJM, Novak AR, Pluss MA, Coutts AJ, Fransen J. Assessing the validity of a video-based decision-making assessment for talent identification in youth soccer. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(6):729–34. pmid:30587435 - 6.

de Joode T, Tebbes DJJ, Savelsbergh GJP. Game insight skills as a predictor of talent for youth soccer players. Front Sports Act Living. 2021;2:609112. pmid:33521633 - 7.

Timmerman EA, Savelsbergh GJP, Farrow D. Creating appropriate training environments to improve technical, decision-making, and physical skills in field hockey. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2019;90(2):180–9. pmid:30794115 - 8.

Turner AP, Martinek TJ. An investigation into teaching games for understanding: effects on skill, knowledge, and game play. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(3):286–96. pmid:10522286 - 9.

Larkin P, Mesagno C, Berry J, Spittle M, Harvey J. Video-based training to improve perceptual-cognitive decision-making performance of Australian football umpires. J Sports Sci. 2018;36(3):239–46. pmid:28282740 - 10.

Piggott B, Müller S, Chivers P, Cripps A, Hoyne G. Small-sided games can discriminate perceptual-cognitive-motor capability and predict disposal efficiency in match performance of skilled Australian footballers. J Sports Sci. 2019;37(10):1139–45. pmid:30424715 - 11.

Gabbett T, Rubinoff M, Thorburn L, Farrow D. Testing and training anticipation skills in softball fielders. Int J Sport Sci Coach. 2007;2(1):12–7. https://doi.org/10.1260/174795407780367159 - 12.

Hopwood MJ, Mann DL, Farrow D, Nielsen T. Does visual-perceptual training augment the fielding performance of skilled cricketers? Int J Sport Sci Coach. 2011;6(4):523–36. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.4.523 - 13.

Pagé C, Bernier P-M, Trempe M. Using video simulations and virtual reality to improve decision-making skills in basketball. J Sports Sci. 2019;37(21):2403–10. pmid:31280685 - 14.

Nimmerichter A, Weber N, Wirth K, Haller A. Effects of video-based visual training on decision-making and reactive agility in adolescent football players. Sports. 2016;4(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports4010001 - 15.

Green CS, Strobach T, Schubert T. On methodological standards in training and transfer experiments. Psychol Res. 2014;78(6):756–72. pmid:24346424 - 16.

Alsharji KE, Wade MG. Perceptual training effects on anticipation of direct and deceptive 7-m throws in handball. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(2):155–62. pmid:25917061 - 17.

Silva AF, Ramirez-Campillo R, Sarmento H, Afonso J, Clemente FM. Effects of training programs on decision-making in youth team sports players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:663867. pmid:34135822 - 18.

Panchuk D, Klusemann MJ, Hadlow SM. Exploring the effectiveness of immersive video for training decision-making capability in elite, youth basketball players. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2315. pmid:30538652 - 19.

Conejero Suárez M, Prado Serenini AL, Fernández-Echeverría C, Collado-Mateo D, Moreno Arroyo MP. The effect of decision training, from a cognitive perspective, on decision-making in volleyball: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3628. pmid:32455852 - 20.

Gil-Arias A, Moreno MP, García-Mas A, Moreno A, García-González L, Del Villar F. Reasoning and action: implementation of a decision-making program in sport. Span J Psychol. 2016;19:E60. pmid:27644584 - 21.

Bruce L, Farrow D, Raynor A, Mann D. But I can’t pass that far! The influence of motor skill on decision making. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13(2):152–61. - 22.

Mathôt S, Schreij D, Theeuwes J. OpenSesame: an open-source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2012;44(2):314–24. pmid:22083660 - 23.

Gorman AD, Farrow D. Perceptual training using explicit and implicit instructional techniques: does it benefit skilled performers? Int J Sport Sci Coach. 2009;4(2):193–208. https://doi.org/10.1260/174795409788549526 - 24.

Hayes SJ, Elliott D, Andrew M, Roberts JW, Bennett SJ. Dissociable contributions of motor-execution and action-observation to intramanual transfer. Exp Brain Res. 2012;221(4):459–66. pmid:22821082 - 25.

Maslovat D, Hodges NJ, Krigolson OE, Handy TC. Observational practice benefits are limited to perceptual improvements in the acquisition of a novel coordination skill. Exp Brain Res. 2010;204(1):119–30. pmid:20496059 - 26.

Foster NC, Bennett SJ, Pullar K, Causer J, Becchio C, Clowes DP, et al. Observational learning of atypical biological kinematics in autism. Autism Res. 2023;16(9):1799–810. pmid:37534381 - 27.

Van Pelt KL, Lapointe AP, Galdys MC, Dougherty LA, Buckley TA, Broglio SP. Evaluating performance of National Hockey League players after a concussion versus lower body injury. J Athl Train. 2019;54(5):534–40. pmid:31084502 - 28.

Gil-Arias A, Garcia-Gonzalez L, Del Villar Alvarez F, Iglesias Gallego D. Developing sport expertise in youth sport: a decision training program in basketball. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7392. pmid:31423354

Rec Sports

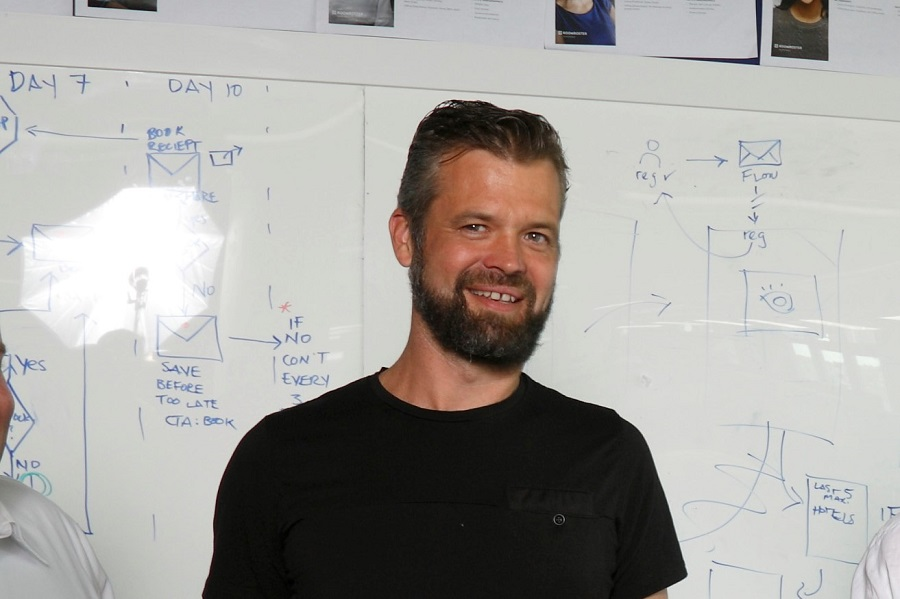

How a Former Rockstar Rebuilt the Business of Youth Sports Travel

When a former rock musician steps in to fix an $11 billion industry problem, you pay attention.

Meet John D’Orsay. Long before he became a tech founder, he spent his late teens and early twenties chasing a career in music. But when the touring life didn’t pan out, he pivoted to his other passion: building software. That shift ended up transforming one of the most overlooked sectors in youth sports.

Back in 2013, as John and his co-founder, Eric, were shuttling their kids across the country for tournaments, they kept running into the same frustrating reality: booking hotels for youth sports travel was a mess. Each event used a different system or no system at all. Families jumped between clunky websites, spreadsheets, and unofficial “group links,” all while knowing they probably weren’t getting the best rates.

So John built a solution.

What started as a simple, free tool to help organizers and families coordinate lodging has since evolved into EventConnect, a platform that centralizes hotel bookings for youth tournaments nationwide.

The model is straightforward but powerful: by aggregating demand from entire teams, EventConnect negotiates lower, guaranteed rates with hotel partners. Families benefit from better pricing, closer proximity to venues, and more reliable amenities. Hotels benefit from thousands of room nights secured months in advance. Tournament operators get real-time reporting and a smoother travel experience for every attending team.

And the market responded fast. Even in its earliest form, EventConnect signed 15 clients within a single month of launching.

But the real significance lies in what the company foreshadowed. When John and Eric started, youth sports travel was still seen as a niche side segment. Today, lodging alone in the youth sports economy represents nearly $11 billion annually a staggering figure for an industry many still underestimate.

Not bad for a former rockstar with a backup plan.

About Youth Sports Business Report

Youth Sports Business Report is the largest and most trusted source for youth sports industry news, insights, and analysis covering the $54 billion youth sports market. Trusted by over 50,000 followers including industry executives, investors, youth sports parents and sports business professionals, we are the premier destination for comprehensive youth sports business intelligence.

Our core mission: Make Youth Sports Better. As the leading authority in youth sports business reporting, we deliver unparalleled coverage of sports business trends, youth athletics, and emerging opportunities across the youth sports ecosystem.

Our expert editorial team provides authoritative, in-depth reporting on key youth sports industry verticals including:

- Sports sponsorship and institutional capital (Private Equity, Venture Capital)

- Youth Sports events and tournament management

- NIL (Name, Image, Likeness) developments and compliance

- Youth sports coaching and sports recruitment strategies

- Sports technology and data analytics innovation

- Youth sports facilities development and management

- Sports content creation and digital media monetization

Whether you’re a sports industry executive, institutional investor, youth sports parent, coach, or sports business enthusiast, Youth Sports Business Report is your most reliable source for the actionable sports business insights you need to stay ahead of youth athletics trends and make informed decisions in the rapidly evolving youth sports landscape.

Join our growing community of 50,000+ industry leaders who depend on our trusted youth sports business analysis to drive success in the youth sports industry.

Stay connected with the pulse of the youth sports business – where industry expertise meets actionable intelligence.

Sign up for the biggest newsletter in Youth Sports – Youth Sports HQ – The best youth sports newsletter in the industry

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow Youth Sports Business Report Founder Cameron Korab on LinkedIn

Are you a brand looking to tap into the world’s most passionate fanbase… youth sports?

Introducing Play Up Partners, a leading youth sports marketing agency connecting brands with the power of youth sports. We specialize in youth sports sponsorships, partnerships, and activations that drive measurable results.

About Play Up Partners

Play Up Partners is a leading youth sports marketing agency connecting brands with the power of youth sports. We specialize in youth sports sponsorships, partnerships, and activations that drive measurable results.

Why Sponsor Youth Sports?

Youth sports represents one of the most engaged and passionate audiences in sports marketing. With over 70 million young athletes and their families participating annually, the youth sports industry offers brands unparalleled access to motivated communities with strong purchasing power and loyalty.

What Does Play Up Partners Do?

We’ve done the heavy lifting to untangle the complex youth sports landscape so our brand partners can engage with clarity, confidence, and impact. Our vetted network of accredited youth sports organizations (from local leagues to national tournaments and operators) allows us to create flexible, scalable programs that evolve with the market.

Our Approach

Every partnership we build is rooted in authenticity and value creation. We don’t just broker deals. We craft youth sports marketing strategies that:

- Deliver measurable ROI for brand partners

- Create meaningful experiences for athletes and families

- Elevate the youth sports ecosystem

Our Vision

We’re positioning youth sports as the most desirable and effective platform in sports marketing. Our mission is simple: MAKE YOUTH SPORTS BETTER for athletes, families, organizations, and brand partners.

Common Questions About Youth Sports Marketing

Where can I sponsor youth sports? How do I activate in youth sports? What is the ROI of youth sports marketing? How much does youth sports sponsorship cost?

We have answers. Reach out to info@playuppartners.com to learn how Play Up Partners can help your brand navigate the youth sports landscape.

Youth sports organizations: Interested in partnership opportunities? Reach out to learn about our accreditation process.

Rec Sports

Kodiak and U.S. Ski & Snowboard Partner to Fuel Athletes with Nutrition and Training Support Ahead of Milano Cortina 2026

The leader in protein-packed, whole grain products will stock the U.S. Ski & Snowboard USANA Center of Excellence powered by iFIT kitchen, support athlete nutrition and expand its presence across winter sports as athletes prepare for the 2026 Olympic & Paralympic Winter Games

PARK CITY, Utah, Dec. 9, 2025 /PRNewswire/ — Kodiak, the brand known for its high-protein, whole-grain breakfast and snack products, today announces its partnership with U.S. Ski & Snowboard as they gear up for the 2026 Milano Cortino Olympic & Paralympic Winter Games in February and March.

Through the partnership, Kodiak will broaden its presence in winter sports and add to its established network of athlete relationships in trail running, cycling, climbing and more. As part of the agreement, Kodiak will support upgrading the U.S. Ski and Snowboard kitchen at the USANA Center of Excellence powered by iFIT. This will help to ensure the athletes have access to whole-grain, protein-packed foods essential for sustaining the demanding training loads essential to world-class performance.

“U.S. Ski & Snowboard embodies the drive, resilience and love of the outdoors that also inspires us and our commitment to feeding epic days and wilder lives,” said Val Oswalt, Chief Executive Officer of Kodiak. “We are honored to stand behind these world-class athletes in our home of Park City and provide the fuel they need to secure their next podium win.”

“We are delighted to partner with our friends just down the road in Park City,” said Sophie Goldschmidt, President & CEO of U.S. Ski & Snowboard. “Its a natural fit – their product is already a staple with our athletes, and their experience in the industry in a bonus. We’re also looking forward to revitalizing our newly named “Kodiak Kitchen” at our headquarters.”

About Kodiak

On a mission to “Feed Epic Days and Wilder Lives,” Kodiak inspires people to live wilder, wide-open lives by feeding epic days through real breakfasts. Mountain raised among the Wasatch Mountains of Park City, UT, Kodiak strives to make breakfast un-boring – outfitting everyone who is hungry to get out and expand the day’s range with delicious, filling, whole grain greatness while nourishing the land, lives and wildlife that sustain us. For over 30 years, Kodiak has created real, protein-packed breakfasts with honest and carefully selected ingredients, with no artificial preservatives, flavors, or colors. For more information about Kodiak, please visit www.kodiakcakes.com or follow the adventure on Instagram @KodiakCakes.

About U.S. Ski & Snowboard

U.S. Ski & Snowboard is the Olympic and Paralympic National Governing Body of ski and snowboard sports in the USA, based in Park City, Utah. Started in 1905, the organization now represents nearly 240 elite skiers and snowboarders competing on 10 teams, including the Stifel U.S. Ski Team: alpine, cross country, freestyle moguls, freestyle aerials, freeski, nordic combined, Para alpine and ski jumping, the Toyota U.S. Para Snowboard Team and the Hydro Flask U.S. Snowboard Team. In addition to the elite teams, U.S. Ski & Snowboard also provides leadership and direction for tens of thousands of young skiers and snowboarders across the USA, encouraging and supporting them in achieving excellence. By empowering national teams, clubs, coaches, parents, officials, volunteers and fans, U.S. Ski & Snowboard is committed to the progression of its sports, athlete success and the value of team. For more information, visit www.usskiandsnowboard.org.

Kodiak Media Contact

[email protected]

[email protected]

SOURCE Kodiak

Rec Sports

Unrivaled Sports Announces Long-Term Investment in Twin Creeks Sports Complex

Twin Creeks Sports Complex to undergo major enhancements as Unrivaled Sports deepens its commitment to Bay Area youth sports

SUNNYVALE, Calif., Dec. 9, 2025 /PRNewswire/ — Unrivaled Sports, the nation’s leader in youth sports experiences, today announced the acquisition of Twin Creeks Sports Complex, a recreational landmark in Santa Clara County and the broader South Bay community.

As new leaders of this complex, Unrivaled Sports will invest in Twin Creeks and partner with the communities in Santa Clara County to enhance and expand local and national youth sports opportunities at the facility. Unrivaled Sports plans to preserve the legacy of Twin Creeks while elevating the venue through thoughtful property improvements and diverse sports programming to welcome even more athletes and their families.

“We are thrilled to welcome the Twin Creeks Sports Complex into our growing network of premier youth sports venues and to work hand-in-hand with the communities in Santa Clara County to usher in the next chapter of this long-standing facility,” said Wade Martin, Chief Commercial Officer and CEO, Baseball of Unrivaled Sports. “Our commitment is to elevate Twin Creeks into a truly top-tier sports venue — investing in the improvements and enhancements needed to create a best-in-class experience for athletes, families and fans for years to come.”

Unrivaled Sports plans to invest millions in targeted facility upgrades that will elevate the quality of play and improve the overall experience for athletes and families at Twin Creeks. The company has a proven record of transforming and revitalizing youth sports venues — including recent enhancements across Ripken Baseball facilities and Big League Dreams in Manteca, California — and is ready to bring that same level of investment and care to the next chapter of Twin Creeks.

“The Santa Clara County Parks Department welcomes Unrivaled Sports as our new partner to operate Twin Creeks,” said Todd Lofgren, Director of Santa Clara County Parks. “This partnership reaffirms the Department’s commitment to providing and increasing access to outstanding recreational opportunities within a diverse regional park system for all Santa Clara County residents. Twin Creeks provides local youth spaces to recreate, supporting healthy lifestyles and better public health outcomes for all.”

As part of the Unrivaled Sports family, Twin Creeks will offer a diverse range of programming for local youth athletes, including leagues, clinics and multi-sport opportunities. By expanding the youth sports programming at the facility, Unrivaled Sports aims to enrich the recreational landscape of the South Bay while supporting the next generation of athletes.

Rec Sports

Recreation association announces 2026 sponsorship tiers for youth sports

Click the + Icon To See Additional Sharing Options

The Green Hills Recreation Association has released its sponsorship opportunities for 2026, offering four levels of support for youth sports programs.

The bronze package, priced at $399 or less, provides sponsors with a group banner.

The silver package, set at $400, includes exclusive team sponsorship for one sports season, a name and logo displayed on player shirts, and one individual banner for the summer league.

The gold package, available for $550, offers exclusive team sponsorship for two sports seasons, a name and logo on player shirts, and one individual banner for the summer league.

The platinum package, listed at $750, includes exclusive team sponsorship for three sports seasons, a name and logo on player shirts, and two individual banners for summer leagues.

All sponsorship levels include recognition on the Green Hills Recreation Association’s website and social media platforms.

Sponsorships help offset the cost of equipment, uniforms, facility and field rentals, maintenance, and other expenses associated with youth sports. Scholarships are available to ensure participation across all income levels.

Sponsorship requests are filled on a first-come, first-served basis.

Anyone interested in a sponsorship is asked to contact Cara McClellan by December 31 with a requested sponsorship level. She can be reached at 660-359-3973 or 660-359-1301.

Post Views: 0

Related

Click the + Icon To See Additional Sharing Options

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoFirst Tee Winter Registration is open

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoFargo girl, 13, dies after collapsing during school basketball game – Grand Forks Herald

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoCPG Brands Like Allegra Are Betting on F1 for the First Time

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoF1 Las Vegas: Verstappen win, Norris and Piastri DQ tighten 2025 title fight

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoTwo Pro Volleyball Leagues Serve Up Plans for Minnesota Teams

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoUtah State Announces 2025-26 Indoor Track & Field Schedule

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoSycamores unveil 2026 track and field schedule

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoRedemption Means First Pro Stock World Championship for Dallas Glenn

-

NIL1 week ago

NIL1 week agoBowl Projections: ESPN predicts 12-team College Football Playoff bracket, full bowl slate after Week 14

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoTexas volleyball vs Kentucky game score: Live SEC tournament updates