Rec Sports

An NFL player was against ‘shrink dudes.’ Then he started working with one

Editor’s note: This story is a part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and success through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

When Doug Baldwin first met the sports psychologist who would have a profound impact on his life, he was skeptical about working with him.

“Skeptical is kind of a nice way of putting it,” Baldwin said. “I was against it.”

It was 2011, and Baldwin had just joined the Seattle Seahawks as an undrafted rookie. The draft snub fed his intensity and insecurities. For years, he had used the feeling that he wasn’t good enough to prove that he was. That combination had helped him reach the pros, going from an unheralded two-star prospect out of high school to Stanford’s leading receiver as a senior. When he made a mistake, he dwelt on it and used it to knock his self-worth, prompting him to work even harder.

Only later, as he learned how to frame and consider his internal thoughts, did he truly understand the personal costs of that mindset.

So when Baldwin met Dr. Michael Gervais, a sports psychologist that Seahawks coach Pete Carroll had brought in to work with players, he wasn’t sold. Baldwin believed the way he had always carried himself was what made him a successful football player. And when Gervais walked in with his fluffy hair, polished style and frequent smile, Baldwin thought he looked like a Tom Cruise clone.

A teammate in Seattle, running back Marshawn Lynch, had a name for people like Gervais: “shrink dudes.”

Yet when Gervais explained the intent of his work — to unlock the best versions of players through training their minds — and the goals it could help them achieve, Baldwin decided to give him a shot.

If this is what he says it is, Baldwin thought, then why not just try it?

For Gervais, that initial meeting came as he was returning to the sports world after his first attempt to work with athletes a decade earlier had frustrated him.

He had earned a Ph.D in sports psychology with the belief that all athletes could benefit from his work. But he became deflated when he felt like some of his athletes didn’t fully believe in the correlation between mental skills training and performance, and even more so when they didn’t match his investment.

So instead, he spent time at Microsoft, helping high-performers develop mental skills and playing a crucial role in the Red Bull Stratos project, where he counseled Felix Baumgartner before his record-setting skydive from 128,000 feet.

In 2011, Gervais had dinner with Carroll before his second season as the Seahawks’ head coach. Carroll explained that he was looking to instill a culture built around training players’ minds as much as their bodies, and he assured Gervais it would be different from his previous experiences. So Gervais decided to give pro sports another chance.

The first time Gervais worked with Baldwin was during a group session about basic breathing exercises. He started the session with box breathing. Baldwin and his teammates inhaled for five seconds, paused at the top for five seconds, exhaled for five seconds, then paused at the bottom for five seconds before breathing in again.

Next, they switched to down-regulation breathing: inhaling for eight seconds, pausing, exhaling for 16 seconds, then pausing again.

Before the session finished, Gervais asked the group to participate in a “gratitude meditation.”

“It’s completely attuning to one thing you’re grateful for,” Gervais said.

Afterward, as Gervais exchanged goodbyes with players, Baldwin slowly made his way to the front of the room. Gervais wasn’t sure what Baldwin was going to say. When they were face to face, Baldwin just stood there, grinning and nodding his head up and down.

“OK,” Baldwin finally said. “Yep. OK.”

Gervais didn’t have to say anything back.

“I knew and he knew what that stood for,” Gervais said. “OK, I just went somewhere. I just felt something.”

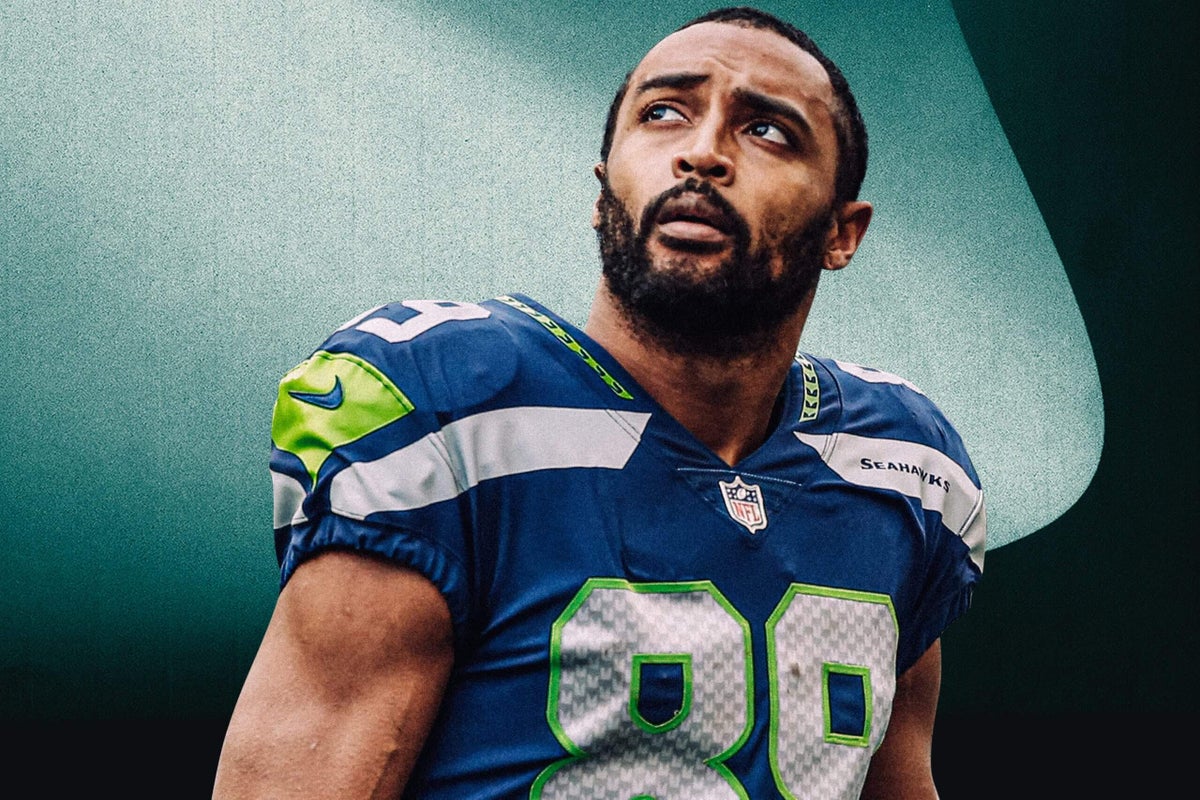

Baldwin was never the biggest or fastest receiver, but he was always one of the most prepared players on the Seahawks. (Abbie Parr / Getty Images)

Baldwin’s work with Gervais came at a time when athletes across sports started to more publicly consider their mental health and how it influenced their performance. Baldwin felt the stigma against showing signs of vulnerability. However, the revolution has continued and has changed how athletes discuss their struggles, with many more publicly acknowledging the ways they are seeking help.

“Being able to do that opened up a whole different realm for me,” Baldwin said.

The first breath-work session had been a “gate opener,” the first time that he felt like he could control his intense emotions.

“My body had never felt that type of stillness and that type of relaxation,” he said.

Still, Baldwin’s skepticism didn’t vanish overnight. Gervais chipped away at it by painting a picture. As thoughts came into his mind, Gervais suggested viewing them as clouds: Just like a cloud, the thought is here right now, but it’s simply passing through the sky. Just because a thought existed didn’t mean Baldwin needed to have judgment of it. It’s not a bad thought or a good thought. It’s just a thought. And it floats by just as a cloud does.

He also connected with Baldwin on a personal level. It wasn’t unusual for their check-ins to turn into hours-long conversations, or for shared meals in the lunchroom to extend into a long walk-and-talk session to practice.

“It was basically counseling sessions,” Baldwin said. “It was about finding a deeper understanding of myself and what I’m capable of.”

Gervais helped Baldwin understand his intense emotions and energy with an analogy: “It’s like you’re trying to dictate which way a herd of mustangs is going. You’re not going to be able to do that. What you can try to do is try to guide them in the general direction that you want to go.”

Baldwin gained a deeper understanding of himself and his thought processes. Conversations with Gervais helped Baldwin connect many aspects of his mindset to the difficulties of his childhood and his insecurities, which gave him the awareness to make adjustments. By getting to the source and working to improve his thoughts, he began to see his relationships and life off the field improve as well.

Baldwin began breath work twice a day, and the physical and mental benefits surprised him. He could stay calm under pressure moments on the football field, but he also felt more peaceful and relaxed in his regular life.

Gervais helped him establish a pre-performance routine, a pregame routine and a pre-snap routine. Most importantly, from Gervais’ perspective, each part of every routine put Baldwin in control. Baldwin could not control scoring touchdowns, for example, but he could control the way he caught the ball or moved his feet.

This, Gervais explained, allowed Baldwin to “put himself in the best position to be himself.”

The purpose was to master how to stay calm under stress, generate confidence, envision performance excellence, let go of mistakes and be a better teammate.

“Thoughts drive actions,” Gervais said. “Thoughts impact emotions. Thoughts and emotions together impact behavior. And thoughts, emotions and behavior stacked up is what creates performance.”

Baldwin incorporated visualization into his routine. He would imagine himself making specific plays to convince his mind that the moment had already happened — another way to give himself a sense of control.

Baldwin’s insecurity-fueled drive didn’t disappear. He was always one of the Seahawks’ most prepared players. He studied film for hours and prioritized going into games, confident that he had done everything to give himself the best chance to be successful.

Still …

“No matter how hard you prepare,” Baldwin said, “there’s always something that comes up that you weren’t prepared for or makes you question your preparation.”

That’s where the work with Gervais kicked in.

During a big playoff game, Baldwin’s heart pounded so rapidly that he began to feel anxious.

“Just get grounded,” he told himself. “Get grounded.”

As he pressed his thumbs to each of his fingertips, he continued to take deep breaths, reminding himself of where he was and the techniques he had learned from Gervais.

“I’m in control of my body, I’m connected to it,” he recited.

Then the game started and Baldwin began to feel like himself. His training with Gervais didn’t always yield immediate results.

In 2016, when the Seahawks played the Green Bay Packers, Baldwin struggled. Nothing he tried was successful. He couldn’t bring himself to be balanced and grounded. But he didn’t give up.

“It’s consistency and discipline with it, but then also persevering through those times where it may feel like it’s not working,” he said. That paid off in a major way that year, when he had the most catches and most receiving yards of his career and made his first Pro Bowl.

“It’s somewhat similar to a muscle,” Baldwin said. “You have to work it out in order to strengthen it, and there are going to be times where it fails because that’s the only way that it grows and gets stronger.”

After big games that season, he sat on the sideline and thought: Damn. He didn’t feel tired; everything felt effortless.

As his work with Gervais continued, Baldwin noticed changes off the field. He felt more confident and reliable as a friend, husband, brother and son.

Baldwin retired at 30 after the 2018 season. He wanted to ensure that the adverse side effects of his many years playing football did not interfere with his kids and family. He and his wife, Tara, have three daughters, and he feeds his competitive side with pickup basketball games.

Without football, he finds himself occasionally tempted to fall back into old habits because deep down they still feel safer to him, and more familiar. But he still relies on the blueprint Gervais gave him years ago to catch himself.

On his phone, he has one of Gervais’ guided meditation recordings. When he wakes up some mornings, he does breathing exercises and visualizes how his day is going to go — the same tools he used to catch passes and score touchdowns.

“And that’s been profound in my life,” Baldwin said.

Elise Devlin is a writer for Peak. She last wrote about the best ways to coach youth sports. Follow Peak here.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Otto Greule Jr / Getty Images)

Rec Sports

Ace Austin doesn’t play in Alabama women’s basketball’s season opener

Alabama women’s basketball was without its highly-recruited guard Ace Austin during its season opener Monday, Nov. 3, at Coleman Coliseum.

Austin is day-to-day with a quad injury, a source close to the freshman standout confirmed to The Tuscaloosa News.

Austin last saw the court in the 91-71 win over Florida State on Oct. 16 in Birmingham. She was one of four double-digit scorers, racking up 10 points in her first collegiate game exhibition.

She is coming off an ankle injury sustained in last year’s Alabama high school basketball playoffs at Spring Garden. In that senior season, Austin became the first girl to win the ASWA Miss Basketball in back-to-back years.

Amelia Hurley covers high school sports and Alabama softball for The Tuscaloosa News. She can be reached through DM on X at ameliahurley_ or via email at ahurley@gannett.com.

Rec Sports

The Lonely New Vices of American Life

One minor but arresting fact of U.S. history is the huge amount of alcohol the average American consumed in 1830: 7.1 undiluted gallons a year, the equivalent of four shots of 80-proof whiskey every day. Assuming some children wimped out after the first drink, this statistic suggests that large numbers of Jacksonian-era adults were rolling eight belts deep seven days a week, with all the attendant implications for social and political life. Imagine what it was like resolving a buggy accident, let alone conducting a presidential election.

Much has been said about Americans’ supposed national virtues—the mercantile ambition, the Protestant work ethic, the rugged individualism—and the particular character they lend the United States, but comparatively little has been said about national vices. Give your 19th-century plowman a dozen hard ciders, though, and see whether that plays a more significant role in his evening than his urge to pull himself up by his bootstraps. Just as personal vices can shape the course of an individual life, so too can national vices influence our collective experience, maybe as much as our virtues—or possibly even more. And those vices are changing.

Compared with our forebears, Americans barely drink now: a mere 2.5 gallons per capita in 2022. The more striking change, though, is that in a Gallup poll released in August, only 54 percent of respondents said they drank at all—the lowest portion since the analytics company started asking the question in 1939. Although doctors surely approve, this downturn is bad news for those of us who use alcohol for its intended purpose—improving the company of others—to say nothing of its off-label uses in dancing, youth-sports spectating, karaoke, etc.

The decline in drinking coincides with a decline in social activity more broadly. A variety of causes have been blamed for this trend toward isolation, phones chief among them. Maybe the phone theory is correct, and maybe it is not; the forces behind broad national trends are endlessly debatable. At the micro level, however, the influences of different vices become more clear. Consider a night out with friends, and the diverging consequences of buying a round of shots versus opening up Instagram.

The systemic effects of millions more people looking at their phones and millions fewer getting drunk remain to be seen. These are not the only changing national vices, however; more Americans are also gambling online, consuming marijuana, and watching pornography than ever before. And these new, ascendant vices are likely to shape American life in the 21st century as much as mass day drinking shaped life in the 19th.

Nearly half of U.S. states have legalized recreational marijuana since 2012, a change that seems to be causing a massive rise in the number of Americans who use cannabis. Although evidence does not indicate how many people who have given up booze are taking up weed, the percentage of Americans ages 19 to 30 who reported consuming marijuana within the past year went up by 56 percent from 2009 to 2023, according to a University of Michigan report. The increase was even higher in the 35-to-50 cohort, whose portion of marijuana users more than doubled during the same period. These statistics do not include use by minors, which my own unscientific observations suggest has increased approximately one million percent since recreational marijuana became legal in my town in 2023.

Again, these numbers don’t mean that Americans are turning to marijuana instead of alcohol. But marijuana consumption has gone up at the same time that alcohol consumption has gone down, and the qualitative differences between being high and being drunk translate to differences in social behavior. For instance, alcohol can legally be consumed in bars, where one often meets and even talks to other people; meanwhile many states that have legalized recreational marijuana prohibit its use where it is sold, forcing the purchaser to take an additional step in order to get high in company. People can still get high together, obviously, but people who drink in bars are more likely to find themselves socializing whether they mean to or not. Customs surrounding the two drugs differ meaningfully, too. Drinking alone on a regular basis is widely stigmatized as a symptom of alcoholism; the stigma against getting high alone, maybe while you listen to your vinyl copy of G N’ R Lies and look for that goat you saw in the wood paneling one time, is anecdotally weaker.

Is the confluence of decreasing interest in alcohol and increasing interest in marijuana making Americans socialize less? The question cannot responsibly be answered with any certainty, even if one feels that incidents of people getting riled up and burning down the mill owner’s house have gone way down since 1830.

But what is the national character if not a vague feeling? My feeling is that our vices have become more furtive and alone. Consider the massive rise in the most depressing vice I can think of: online gambling. A poll by the Siena College Research Institute found that 48 percent of men ages 18 to 49 have an account with an online sportsbook, an astonishing number that probably has something to do with 39 states having legalized sports betting since 2018. Whereas other forms of gaming require people to sit around the same table, crouch in the same alley, or gather at the same racetrack, online-sportsbook users can gamble in total isolation. Say what you will about gambling’s ruinous effects on fortune and family—at least it has historically brought people together. The poker craze of the aughts, for example, created untold numbers of problem gamblers; it also led them to sit with one another for hours at a time. The difference between millions of Americans trying to read one another’s facial expressions while they reinforce compulsive behavior and millions hunching over their phones to incur a similar risk is not negligible.

Perhaps the phrase hunching over their phones is better applied, though, to another, lonelier 21st-century vice: internet pornography. Some people watch porn together, of course, but one can reasonably assume that most porn is consumed alone. And although erotic images have existed since the dawn of visual representation, internet video pornography and the multibillion-dollar industry that has developed around it make porn at once more available and more potentially time-consuming than ever before. A single DVD or issue of Penthouse gets old; the supply of free porn on the web is bottomless.

People of different moral persuasions have different perspectives on what constitutes sexual vice and how serious a problem it presents, but at least the analog sexual behaviors that are often frowned upon, such as adultery and promiscuity, require meeting people face-to-face. The combination of erotic and parasocial gratification available on a platform such as OnlyFans makes it possible to spend hours a day on sex without ever touching anyone else—a phenomenon to which the emergence of the term pornosexual attests.

I would like to note here that vice persists for a reason. The simple explanation, favored by both clinicians and moral paragons, is that human beings have evolved poor systems for weighing the immediate pleasures of vice against the long-term costs—so we give in. This psychological mechanism is evident in the serious problems of addiction that can emerge from vices, particularly from alcohol and drug use but also from gambling and, in some assessments, compulsive consumption of porn. Because these individual problems are well known, vice is often blamed for so-called social problems: ongoing crises in public health, increased household debt, broken relationships, and other costs, both quantifiable and uncountable, of people pursuing things that feel good but are ultimately bad for them.

At the same time, I hope some readers will agree that although the old vices had net negative effects on some people’s lives, their benefits—for those who pursued vice in moderation—went beyond instant gratification to something more valuable. To spend Saturday night at the bar is, in many cases, to spend time with friends and meet new people. To give in to one’s carnal urges is to experience increased oxytocin levels in the short term and, in certain cases, to find lasting companionship. And gambling at a casino, while it is almost never a smart investment, is at least an excuse to get out of the house, chat, and experience the particular type of empathy that comes from losing alongside strangers. Vice can bring people out of themselves to be with others, even if that means coming together to do what they probably should not.

That the new vices are so uniformly solitary suggests that the national character might become more solitary, too. This trend is unsettling, but perhaps more alarming is that large numbers of people could become so oblivious to the upside of vice as to decide that it is better pursued alone. I would hate to think that, in our collective understanding of sex and gambling and getting wasted, so many Americans would conclude that the endorphins are the only point.

Rec Sports

City of Lawrence wanted almost $1,700 for Sports Pavilion Lawrence financial info – The Lawrence Times

Share this post or save for later

As part of the reporting for an article about fees coming soon to the city’s rec centers, this publication filed an open record request weeks before the commission’s vote to approve the fees, seeking information about Sports Pavilion Lawrence’s revenue and expenses.

The City of Lawrence asked for $1,680 and 30 days to complete the request. City Clerk Sherri Riedemann said the records were housed in multiple systems and would take 48 staff hours to compile.

After asking for a way to lower the cost of the request, the city offered to provide financial data for the past two years at no charge. That information was supplied more than a month later.

But because of the city’s budgeting system, that data doesn’t account for revenue from all activities that take place at the facility, making accurate tracking of the financial status of SPL challenging.

The data provided showed that the facility was running deficits of approximately $925,000 and $1 million in 2023 and 2024, respectively, but those numbers didn’t include revenue from youth sports and other activities that are accounted for in other places.

Don’t miss a beat … Click here to sign up for our email newsletters

Click here to learn more about our newsletters first

The city’s Sound Fiscal Stewardship commitment says: “We provide transparent, easy access to relevant, accurate data for budgeting and decision making.”

Holly Krebs, lead organizer for the Coalition for Collaborative Governance, said the group has had its own challenges seeking transparent financial information from the city. The advocacy group has done work investigating the city’s budget priorities.

She said the city does not consistently provide accessible financial data.

In one example, Krebs said the coalition was unable to find the city’s treasurer’s reports, which document revenue, investments, debt and more, and the city is legally required to publish. After asking the city for them, Krebs said, they were provided the most recent report, but not past years’.

“Our coalition has asked the city to clarify many details of their budget, and we have often had to ask the same question multiple times over weeks or months in order to receive an answer,” she said.

The city’s communications department did not respond to a request for comment on the open record request.

Read the main article at this link.

If local news matters to you, please help us keep doing this work.

Don’t miss a beat — get the latest news from the Times delivered to your inbox:

Click here to learn more about our newsletters first

Cuyler Dunn (he/him), a contributor to The Lawrence Times since April 2022, is a student at the University of Kansas School of Journalism. He is a graduate of Lawrence High School where he was the editor-in-chief of the school’s newspaper, The Budget, and was named the 2022 Kansas High School Journalist of the Year. Read his complete bio here. Read more of his work for the Times here.

Latest Lawrence news:

Contributed photo

Contributed photo

Share this post or save for later

Local author R.B. Lemberg has won a World Fantasy Award —one of the most prestigious awards for science fiction, fantasy and speculative titles — for a novella in their ongoing speculative fiction series.

Share this post or save for later

The Lawrence school district has launched a food drive to help meet its students’ immediate needs.

August Rudisell/Lawrence Times

August Rudisell/Lawrence Times

Share this post or save for later

A lot of people recall a promise from the city that when Sports Pavilion Lawrence opened, it would forever be free to use. But a dozen years later, there appears to be no solid proof that such a pledge was made, and fees are set to go into effect in January.

Molly Adams / Lawrence Times

Molly Adams / Lawrence Times

Share this post or save for later

Lawrence voters on Tuesday will elect two city commissioners and three school board members. Here’s what voters should know about how and when to cast their ballots, plus where to learn about the candidates.

MORE …

Rec Sports

Champion of the underdogs: Youth soccer coach’s commitment to kids spans 47 years

QuickTake:

Mario Lobo Hernandez has coached kindergarteners through high school seniors. Beyond the soccer pitch, his lifelong political activism and service work, especially in the Latino community, has touched lives.

It was his last championship game, but definitely not his first.

Mario Lobo Hernandez paced the sideline of the Spencer Butte Middle School soccer field, yelling instructions as his seventh- and eighth-grade players neared the goal. They were playing Cottage Grove on the afternoon of Oct. 19.

Hernandez been coaching the oldest boys on his North Eugene Kidsports team for the past five years. Next year, they will move on to high school, and Hernandez will retire from his 47-year run as a Eugene youth soccer coach.

That is, if he can stay off the field.

Hernandez, 81, is known in the Eugene youth soccer world for his rigorous coaching and his passion for the game.

His co-coach, Andrea Pierce, jokes that through his strong Honduran accent “pass the ball” is sometimes all players can make out — and maybe it’s all they need.

“He can be quirky and intimidating in the same breath,” said Gabriel Hernandez, his older son. “It’s a weird mix, but it does somehow unite teams.”

Hernandez coached at North Eugene High School in the 1990s and early 2000s and has since stuck to coaching through the youth sports program Kidsports. Altogether, he’s led 15 recreational and high school teams to championship wins. All of his teams have been on the north side of town, an area not known for its soccer prowess.

Hernandez’s commitment to serving the underdogs isn’t just limited to youth sports, however. It’s been a through line of his whole life.

Beginnings in Honduras

Hernandez doesn’t go by “Mario” in his hometown of Tela, Honduras. There, he’s “Mayito” or “little Mario,” despite his age.

Mayito was raised by his grandmother. He grew up in a home with a dirt floor and got his first shoes when he was 13.

Though he was poor, he made good grades, played several sports and got a scholarship to go to college for journalism in the capital city. He sold fallen mangos to buy his bus fare from Tela to Tegucigalpa.

Tegucigalpa was also where Hernandez got serious about soccer. He played in a semi-professional league during his time in college, but eventually he stopped playing to focus on his studies.

After Hernandez graduated, he took the oath that every journalist in Honduras had to take in order to be a professional in a country where freedom of the press was not guaranteed. He put one hand on the constitution and the other in the air as a man read the journalists their responsibilities.

“Are you ready to lose friends and family?” the man asked them. “Are you ready to be arrested? Are you ready to be beaten? Are you ready to be killed?”

Hernandez was lucky. He wrote plenty of inflammatory stories about the government during his time as a journalist in Honduras, got seven death threats and was arrested three times, but his detentions were brief. He was most proud of his coverage of the Black community in Honduras. Hernandez’s stories held landlords accountable for the community’s miserable living conditions. He still has a copy of tenant rights that he memorized.

Hernandez met his wife, a PeaceCorp volunteer in Honduras, while working as a journalist, and he later moved to Eugene to be with her in 1977.

Just as his older son, Gabriel, inherited Hernandez’s love of playing and coaching soccer, his younger son, Javier, caught the bug for truth-telling. Javier Hernandez is now the Tokyo bureau chief for The New York Times.

The Honduran journalist oath also charged reporters with being the “lawyers of the people,” a commitment to community that Mario Hernandez carries with him to this day.

Friends and family still report back to him about political happenings, like the upcoming election in Honduras. Hernandez writes pieces about national politics, both in Honduras and the United States, in the style of news articles and columns on his Facebook page. Sometimes debates break out in the comments section; other times compliments.

“Magnífico comentario, Mayito,” wrote one commenter in response to an opinion piece on “coward politicians.”

An old-school approach

Nearly halfway through the championship game, Hernandez’s team was winning but only by one goal. The opponent, Cottage Grove, was putting up a fight.

Hernandez paced and yelled while Pierce strategized with her field diagram.

Across the field, parents were invested.

“Oh man, I don’t know about that,” muttered Burke Smejkal, after a referee made a questionable out-of-bounds call against the North Eugene team.

Smejkal is dad to seventh-grader Bodie Smejkal-Alameda on Hernandez’s team. Hernandez’s coaching is old-school, but effective, and he provides at a recreational level the same level of coaching that kids get on expensive club soccer teams, Smejkal said.

In Tela, Hernandez played soccer on the beach all the time with his friends. Soccer was woven into everyday life, unlike the structured kids’ leagues in Eugene.

Gabriel Hernandez remembers his dad taking him to the beach in Florence every Saturday morning to re-create the experience — both for nostalgia and for training. Mario Hernandez took one of his high school teams to Florence one year as well.

“You don’t realize you’re working as hard because you’re on the beach, but it is definitely harder to move and you definitely build strength,” Gabriel Hernandez said.

Rain or shine, Mario Hernandez would always jump in the water at the end of their beach training, forever a kid at heart, his son said.

Back on the championship game field, the referee pulled a yellow card on eighth grader Genki Monteagudo and a chorus of surprise rose from North Eugene parents. Monteagudo was not a player who usually received yellow cards.

“Genki?”

Hernandez raised his arms in the air in protest. He spoke to the referee before letting the matter go.

Malena Simmons, mom of eighth grade forward Lakai Simmons, held her phone up to capture the game for her husband, who was FaceTiming from his military deployment across the world. Simmons coached alongside Hernandez for two seasons when he coached her younger son Maddox.

“‘What are you doing?’ is his famous line,” Simmons said. “It’s complete love, but it’s like high, high expectations.”

Hernandez taught her that getting a skill right is more important than doing lots of different drills during practice, and patience is paramount. During the fall 2025 season, Simmons saw him work his magic to bring the younger half of the team up to the level of the other kids Hernandez had been coaching for years. It took some work to get the older kids to pass the ball to the younger kids, but it finally happened.

A soccer coach himself for Eugene Metro Fútbol Club, Gabriel Hernandez sees the bigger picture of Eugene youth soccer and his dad’s important role in an underserved area.

“Our side of town isn’t really a soccer-friendly side of town — I think that’s more of a south Eugene thing,” Hernandez said. “And yet he produces a lot of youth teams out of north Eugene that tend to do pretty well.”

Mario Hernandez’s players are from a diverse array of backgrounds. During a game in a recent season, one of his players came to the sideline in tears. He told Hernandez that a player on the other team had called him “a monkey,” a racial slur. Standing up for his player, Hernandez later demanded that the league expel the player and the coach. League officials reprimanded the player.

Soccer on Sundays

Hernandez started coaching soccer when he moved to Eugene before he could speak English.

Gabriel Hernandez remembers the early challenges his dad faced as an immigrant in the 1980s and ’90s, including many incidents of racism. He would visit the factory that his dad worked in and see messages like “Go back home” on his dad’s locker. Mario purposefully did not clean the messages off.

“He would make sure that we, as children, saw it, and knew that he wasn’t flustered or angry at it, but it existed,” Gabriel Hernandez said.

After Mario Hernandez passed his English test, he got certified through Lane Community College in drug and alcohol counseling and domestic violence counseling. He then went on to work with inmates as a counselor in the Oregon State Correctional Institution in Salem.

Hernandez’s main clients were men who had beaten or killed their wives and women who had killed their husbands. He figured out how to do small things for them, like sneak a man’s broken glasses out, get them fixed and sneak them back in.

“I treated them like humans,” he said.

Hernandez was a natural leader in his home town in Honduras, always the master of ceremonies for holidays and the organizer of the annual fair. In Eugene, he became a similar figure within the Latino community.

He volunteered for a time at Centro Latino Americano, a mental health center for the Latino community, teaching court-ordered parenting classes for people charged with domestic violence. At other points of his career, he worked for Lane County and the University of Oregon connecting migrant farm workers to resources and education opportunities.

Hernandez also ran the Latino soccer league in Eugene in the late ’90s and early 2000s. Gabriel Hernandez said his dad was able to recreate a feeling of home for many people through the league’s Sunday games at Maurie Jacobs Park, where there were food vendors and Spanish was the predominant spoken language.

“I played with and met a lot of people that had nothing when they came here, but they did have soccer on Sunday, and he made that accessible and affordable,” Gabriel Hernandez said.

Hernandez helped start a Spanish newspaper in Lane County called Noticiero Informativo, which has since been discontinued. He parted ways with the organization because of a disagreement about editorial direction. The newspaper closed soon after he left.

Hernandez is, by nature, political, but he believes in the power of sports to bring people together across party lines. The current political climate has taken a toll on some of his friendships, however.

Hernandez goes to The Keg on West 11th Avenue every Sunday to watch his favorite football team, the Las Vegas Raiders, and spend time with other bar regulars. Recently, however, a couple whom he has been friends with for 24 years stopped talking to him after Hernandez shared his views on President Trump and his crackdown on immigration.

Hernandez himself was stopped by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers in a Fred Meyer parking lot on River Road, even though he is a U.S. citizen.

“I talked about how they treat us like dogs,” Hernandez said.

‘See you on the field’

Hernandez’s team won the Oct. 19 championship, 6-1. The game’s conclusion did not come with jumping and screaming, however. Hernandez hates when teams rub their victories in opponents’ faces.

Instead they had an orderly medal ceremony and four days later, a pizza party at Putters. There was a raffle for Costco-sized food items that Hernandez brought, including a massive box of Frosted Flakes, and parents presented a gift for Hernandez: a new Raiders jacket — complete with a hood for rainy Oregon days.

While he’s told everyone that the short spring season will be his last with Kidsports, Hernandez now questions his decision. Gabriel Hernandez doubts his dad can step away.

“It’s an obsession,” he said. “He has to be out there doing something.”

Even if he doesn’t coach, Mario Hernandez will be around. Parents always spot him at school sports games. Whether it’s a North Eugene High School soccer game or a Kelly Middle School track meet, he shows up to support his current and former players.

As kids chowed down on pizza, Hernandez told the seventh and eighth graders how proud of them he was and apologized, with a smile, for all the yelling. He closed with a promise to the eighth-graders that he has fulfilled for decades of former players.

“I will see you on the field for the next four years,” he said. “I will be there.”

Rec Sports

Safeway Community Services uplifts people with disabilities, youth

Six years ago, Christina Jordan was focused on becoming a tennis star.

At West Virginia University, the Detroit native played on the college team and majored in biochemistry. But, as Jordan entered her senior year, her interest in human behavior took precedence over studying living organisms.

The decision to switch her major to psychology was personal – Jordan’s twin brothers Christopher and Christian have intellectual disabilities and she wanted to find a way to assist them with life’s challenges, she told BridgeDetroit.

“I’m definitely inspired by my family, and I have a purpose that I’m trying to carry out,” Christina Jordan said.

After graduating from WVU in 2020, Jordan found that purpose by teaming up with her mother, Anisha Jordan, to establish Safeway Community Services, a nonprofit organization dedicated to serving youth in underserved communities and individuals with disabilities. In the past three years, Safeway has served around 1,000 people through its autism awareness training, special education support and community events, Chrstina Jordan said, including around 700 people in Detroit.

The organization also offers an independent living program for adults with disabilities.

“My mom and I created (Safeway) to help them (Christopher and Christian), and now we have them semi-independently living on their own,” Christina Jordan, 27, said. “They have support services, they are able to go to school and things like that. Once we figured out that the system that we created works, we wanted to be able to share that with other people.”

One of Safeway’s signature initiatives is a free youth summer sports camp, where kids can learn how to play football, tennis, track and field, as well as cheer and dance. The camp has taken place at West Bloomfield High School and Metropolitan Racquet Club in past years. While the program was not offered in 2025, Christina Jordan said she hopes to bring it back next year.

Safeway has programming for a broad range of age groups, Christina Jordan said. About 80% of the children served come from Detroit Public Schools Community District, with others coming from nearby cities like Redford and Southfield.

“For the autism awareness program, those are typically all ages because we’re spreading awareness to not only the kids, but to the caregivers,” she said. “Our programs range from youth as small as three and it goes all the way up until 35.”

Another Safeway program is designed for people with or without disabilities who were formerly enrolled in college and wish to return.

“We’re working on bridging the gap and helping individuals go back to college,” added Anisha Jordan, a special education teacher. “We partner with Talladega University in Alabama, and we’re looking to expand that and get more colleges on board.

“We want to provide extended services to these individuals, whether it’s into homes, education, transportation.”

The majority of the nonprofit’s programming and events are self-funded by the Jordans. However, the organization has started to receive interest from donors this year, Christina Jordan said.

Safeway does not currently have a physical location open to the public, the organization meets the community in schools, libraries and online, Christina Jordan said. She hopes to eventually open an office space in downtown Detroit.

On the Jordans’ agenda for next year is a plan to expand Safeway’s teen mentorship program, Safe Track. Along with the existing program in Detroit, Safe Track will be offered in Houston, Pittsburgh and Charleston, West Virginia.

Houston has been home for Christina Jordan for the last three years and she has ties to Charlestown and Pittsburgh from her college years. In August, Safeway held a back-to-school drive in South Charleston and a financial literacy workshop for Pittsburgh Public Schools in September.

“I just noticed that those kids are eager to learn, and being able to spread and share the support that we have with other people is super important,” Christina Jordan said. “I want to be able to expand that across the US.”

On Nov. 7, Safeway is hosting its “Seeds of Tomorrow” gala in Houston, where funds will go toward launching its expanded mentorship programs. The organization plans to hold a gala in Detroit next year, Christina Jordan said.

“The focal point of the fundraiser is helping each kid (in the mentorship program) be able to have a mentor for whatever they want to do, whether that’s a football career or they want to be a scientist,” Thomas said. “We’re really excited, and I think it’ll be a good opportunity to show people what Safeway is all about.”

Creating a safe space

Anisha Jordan began her teaching career more than 20 years ago at DPSCD, working with students at the Drew Transition Center and the now-closed Cooley High School. She’s now with the Redford Union School District.

The Jordans came up with the name Safeway because they want to provide a safe space for the people they serve, she said.

“That’s how I’ve always built my environments,” Anisha Jordan said. “It’s about safety first, whether they’re at home or in the schools. When working with people with disabilities, you gotta have the right people around you.”

The Jordans mostly work with people with cognitive disabilities like autism, as well as people with physical disabilities. People can sign up for the organization’s programs by calling or sending a message through the website. Donations to Safeway can be made via its Zeffy page.

Since the mother and daughter can’t handle everything on their own, they hire contract staffers and interns to facilitate programs and events, Christina Jordan said.

Safeway’s program lead Gia Thomas was initially brought on for graphic design work and to build the organization’s website. Thomas’ responsibilities have since expanded to event planning.

“They recently had a celebrity softball game where I was able to really show what I can do,” Thomas said. “The program went really well, so they brought me on for the rest of the events since then.”

Keeping the faith

As an athlete, Christina Jordan knew she had to incorporate sports into Safeway’s programming.

One of the biggest events the nonprofit has hosted so far is its inaugural celebrity softball game in June at The Corner Ballpark in Corktown. The all-star local roster included R&B artist Ronnie “Detroit Zeus” Irons, Minnesota Vikings player Tavierre Thomas, former Detroit Lions player Joique Bell and rapper Vae Vanilla.

For her part, Thomas organized the softball media team, sponsorship team and grant specialist team. She also prepared for the organization’s first $1,000 scholarship, which was awarded during the event to Lincoln Neely, a Plymouth Canton graduate who was part of the Safe Track program.

Neely, 18, is now studying computer science at Michigan State University. He said Safeway provided him with so much more than the funds. Christina Jordan worked with Neely to help him figure out where he wanted to apply to college, helped him with his essays and explained the financial aid process. She also helped him with time management, which was essential since Neely was a high school swimmer and had trouble balancing practices with classes. As an athlete herself, Christina was able to help him prioritize.

“I faced some challenges adapting to AP classes in high school. I was going to drop them. Christina and the Safeway program helped me stick with it,” he said. “It felt good to know I had people behind me who wanted to see me be successful. Whenever I had a low point, I could go to her for help.”

Neely says he aspires to work for a company like Microsoft or Google to help create or adapt technology to make it easier for everyone to use.

Thomas said it’s important that Safeway donors are able to see the impact of their contributions, whether it’s helping get someone like Neely into a good college or assisting other kids with confidence through sports.

“People will really support you when it’s a good cause,” Thomas said. “And a lot of people, when they’re donating their time and money, they sometimes don’t know where the money’s going. We make sure you see what we’re doing and that’s really important for our events.”

Christina Jordan wants to make the celebrity softball game an annual event and offer more scholarship opportunities in the future.

“I wanted to get people that have a strong influence in the community,” she said about the lineup for the event. “We have a lot of local musicians, artists, rappers, athletes. These are people that our kids look up to, so we tried to get those types of people so they can inspire the younger generation and spread that positivity. Maybe that can influence them to stay on the right path.”

Christina Jordan is already seeing how Safeway is impacting her brothers.

Christopher Jordan is enrolled at Lawrence Technological University in its business management program and Christian is showing an interest in going to the college, she said.

“Seeing how much he’s (Christopher) grown, it really makes me super proud,” Christina Jordan said. “And my other brother, he’s making strides every single day.”

The Jordans said they are excited to see what comes next for Safeway.

“Just to see how far we have come is exciting and inspiring and it motivates us because now we know that we can do this. We only want to keep pushing forward,” Christina Jordan said. “Initially, our goal was to just serve the community in Detroit, but we said over the last year, we noticed that there’s a need in the US and all over the world, so we want to be able to grow as much as possible and serve as many people as possible.”

Meanwhile, Anisha Jordan is enjoying serving others with her daughter by her side.

“Being able to have Christina on my team really helps me,” she said. “I’m happy to be able to teach her to expand herself into the community and be able to help others.”

Related

Rec Sports

WA AG joins multi-state coalition supporting transgender student-athletes’ rights

Washington’s attorney general is backing Minnesota in a fight over transgender student-athletes.

Attorney General Nick Brown officially joined 12 other states in a court brief supporting trans-inclusive sports policies. The coalition is arguing that banning transgender youth from teams that match their gender identity is discriminatory.

“I believe strongly in protecting the rights of all Washington kids — including transgender youth,” Brown said. “Equal access to participation in sports is important to kids’ wellbeing, both emotionally and physically, and barring kids from school athletics because of their gender identity perpetuates the kind of discrimination our state has long sought to abolish.”

The coalition also stated that there is no evidence that transgender girls participating in girls’ contact and competitive skill sports harms cisgender girls, arguing the inclusive culture “creates a more welcoming school and athletic environment for all kids.”

On the flip side, the coalition believes transgender youth are vulnerable to both negative educational outcomes and higher levels of depression due to facing discrimination, threats, harassment, and bullying. Excluding transgender student-athletes from participating in sports that align with their gender identity would increase these risks, according to the coalition.

The states in the coalition — currently comprised of California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington — argued that participation improves mental health and school outcomes for all children.

The case is now before the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals.

This is a developing story, check back for updates

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoThe Woman of the Year Selection Committee has announced the Top 30 honorees for the 2025 NCAA Woman of the Year Award

-

NIL2 weeks ago

NIL2 weeks agoBaylor QB Sawyer Robertson releases Bass Pro Shop trading cards

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoMotorsports and the Growing Accessibility PROBLEM

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoSlow Start Dooms No. 17 Women’s Volleyball in 3-2 Loss at Washington – Penn State

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoMeasles case confirmed in Olmsted County

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoMen’s Cross Country Competes At Princeton Fall Classic

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoCasey Mears Talladega NASCAR Cup Series Notes and Quotes – Speedway Digest

-

Motorsports1 week ago

Motorsports1 week agoWilliam Byron wins pole position for NASCAR Cup elimination race at Martinsville – Speedway Digest

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoCCIW Women’s Volleyball Honors Manojlovic, Britton and Tellor for Standout Week

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoVolleyball Resumes SEC Play With South Carolina and Georgia