Warren Moon and Andre Ware share plenty in common.

NIL

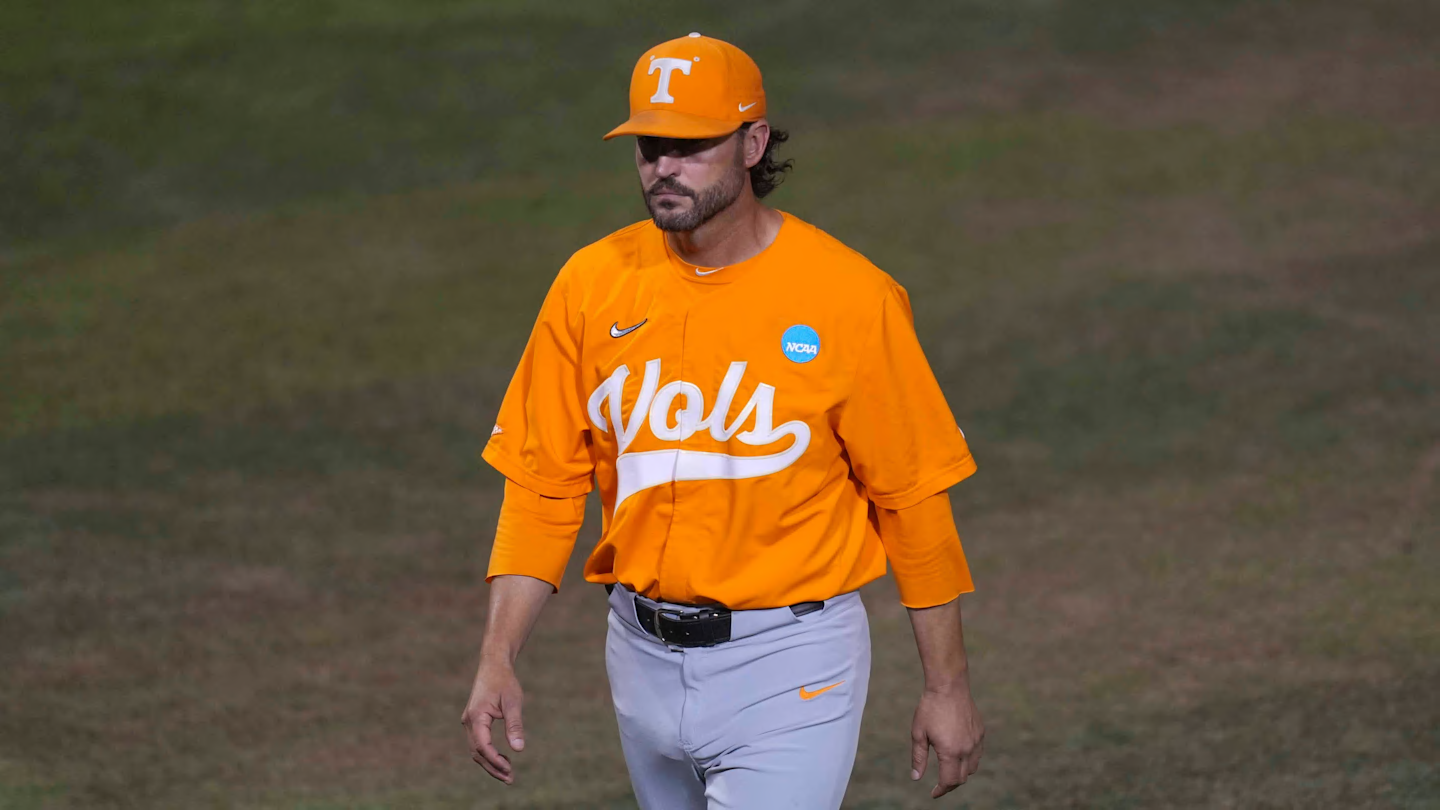

Tennessee Baseball Lands Second

The Tennessee Volunteers have landed the second-best transfer portal class in college baseball.

Transfer portal season has officially died down for college baseball, and the official transfer portal recruiting class rankings have been revealed. The Tennessee Volunteers brought in the second-best transfer class in college baseball, only behind the Georgia Bulldogs.

The Volunteers brought in nine players from the portal this offseason with all nine of those players being ranked inside of the top 250. Five of them rank inside the top 50. The best player they brought in, according to 64analytics rankings, was Henry Ford out of Virginia.

🚨 Final Team Portal Rankings

Here are teams 1-10. @BaseballUGA is number one in our Top 25 Portal Classes for 2025 pic.twitter.com/1oZSSM1jd1

— 64Analytics (@64Analytics) August 8, 2025

Last season at Virginia, Ford smacked 11 home runs, had nine doubles and 46 RBI. He finished the season with a .362 batting average and struck out 30 times compared to 21 walks.

The Volunteers also had a good number of players transfer out of the program, with 24 total electing to do so this offseason, but head coach Tony Vitello and his staff have certainly reloaded the roster with some very talented players.

Follow Our X and Facebook Page

• Follow us on X HERE

• Follow us on Facebook HERE

Follow Our Staff:

Follow Our Website

Make sure to follow our website Tennessee on SI.

OTHER TENNESSEE NEWS

NIL

How To Build A Competitive College Football Roster In The NIL Era

Let’s face it, college football in today’s day and age is nothing like it was even five years ago.

NIL and the transfer portal have introduced new wrinkles – and headaches – for coaches and programs to have to navigate, so building a roster is as complex as it has ever been.

READ: “College Football Is Sick” With NIL Buyouts And Beyond.

I have often found myself gnashing my teeth over the direction of the sport, but today I decided to focus that energy on how exactly to build a roster in this modern era of college football.

Let’s break this down into some key components.

Follow the NFL Model

General manager Howie Roseman of the Philadelphia Eagles. (Photo by Stacy Revere/Getty Images)

It’s not a new development to say that college football is becoming more like the NFL.

With new roles like general manager being created to help deal with the transient and transactional nature of the college game, more and more schools are starting to treat their rosters like NFL operations.

That means abandoning the outdated idea of an 85-man scholarship roster and instead viewing it as a 53-man roster.

Gone are the days of stacking and shelving five-star talent just to keep them waiting in the wings. Most teams are realistically operating with a two-deep at most positions, with the occasional three-deep at high-attrition spots (think trenches).

In reality, you’re paying big money to roughly 35–45 players. Think of the rest as cost-controlled development.

Recruiting now functions more like a draft: cheaper, unproven talent you hope will provide depth and develop without immediately chasing a payday elsewhere.

Which brings us to money.

Budget Allocation and the Tier System

UCLA quarterback Nico Iamaleava. Mandatory Credit: Gary A. Vasquez-Imagn Images

The average Power Four football budget — combining revenue sharing, boosters, and collectives — now sits north of $25 million.

That number is only going up, but for now, it’s a clean baseline.

READ: NIL Wars Between SEC And Big Ten.

The question becomes how to allocate that money without overspending on one player or undervaluing another.

Many general managers use a tier system rooted in NFL positional value, and since college football is mirroring the pros more each year, it makes sense to adopt it.

Tier One

- Starting quarterback

- Edge rusher

- Left tackle

- Cornerback

- X receiver

You could argue WR1 and CB1 sit in a Tier 1.5, but the idea is simple: quarterback is king, and the next most important positions are those that protect your QB and hunt the opposing one.

Tier Two

- Starting running back

- Slot receiver

- Backup quarterback

- Interior offensive and defensive linemen

Linebackers and safeties likely fall into Tier 2.5, if we’re splitting hairs.

A note on running backs: unless you’re dealing with a truly special player (think Saquon Barkley), they sit near the bottom of Tier Two. Their positional value just isn’t very high in today’s game and they wear down quicker than most other positions.

Tier Three

This is a developmental and depth tier, and where a lot of your high school recruiting budget should be spent outside five-star or top-100 high school talent (think low four-star and high three-star players who could develop into quality starters).

Tier Three is where a staff that is great at identifying and evaluating talent earns its pay; anyone can tell you a five-star WR will be a monster, but can you pick out the three-star kid and make him the next Puka Nacua?

Spending Breakdown

Now that we have our position groups identified, it’s time to breakdown where that money will go.

If we stick to the $25 million budget, it would look a little something like this:

Tier One is where roughly half of your funds will go ($11.25 million).

A QB gets 18% of the budget in the NFL, and it’s no different in college, as a high-level P4 starter will pull down a minimum of $3 million, more than likely 4.

Having an elite QB is almost a non-negotiable, but an elite edge rusher and left tackle is almost as important.

You’re probably going to end up spending $1.5 million on two game-wrecking edge rushers and a brick wall at left tackle.

A true WR1 that every defensive coordinator has to game plan for and lose sleep over will also fetch north of $1 million, as will a lockdown CB1.

From there, Tier Two gets a little under $9 million to play with, with your slot receivers and interior linemen eating most of the budget there just through quantity alone.

Tier Three is going to cost around $3–4 million and will be allocated to roughly 40% of your roster, so a lot of these guys will be cheaper depth pieces and younger developmental players.

It seems gross to breakdown college athletes based on what they are worth, but that is just the world we live in these days.

Recruiting vs. Transfer Portal

Finally, we get to my favorite part of the experiment: talent acquisition.

Those of you that are recruiting freaks like myself will be happy to know high school talent acquisition still plays a big role in building a roster, but the transfer portal is vital to any successful college program.

Your high school recruiting philosophy should prioritize Tier One players with super high upside, meaning you should spend on five-star and top-100 level quarterbacks, edge rushers, left tackles, and CB/WR1s.

Other players like interior linemen, safeties, and linebackers should still be recruited out of high school, but you shouldn’t reach for a high-priced talent when a kid who is 80% as good comes at half the cost.

When it comes to the transfer portal, treat it like free agency.

One-year rentals are fine, and you should never portal for depth. This should be to fill glaring holes on the roster.

Tier One is the priority in the portal, especially if you are deficient at a spot like tackle, edge rusher, or receiver.

By having a healthy balance of high school recruiting and the portal (probably a 70-30 split for programs with strong NIL), you can prevent your roster from hollowing out.

And there you have it!

NIL and the transfer portal have made college football almost unrecognizable, and I hate it, but if your team starts to adapt to the new model, they should be fine.

You will start to see more and more teams adapt a model that is similar to the NFL, and although that makes me sad to see, it doesn’t mean college football is mirroring the NFL, rather, it is just mirroring the NFL’s positional value structure.

Hang in there, college football fans. The sport is getting weirder by the day, so let’s all just weather the storm at this point.

NIL

Diego Pavia, JUCO Plaintiffs Seek Another Year of College Football

As he and the Vanderbilt Commodores prepare to play the Iowa Hawkeyes in Wednesday’s ReliaQuest Bowl, quarterback Diego Pavia and 26 other former JUCO football players on Friday asked a federal judge in Tennessee to let them play in 2026 and potentially 2027.

Through attorneys Ryan Downton and Salvador Hernandez, Pavia’s group wants Chief U.S. District Judge William L. Campbell Jr. to issue a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction that would block the NCAA from enforcing applicable eligibility rules pending a final judgment in Pavia v. NCAA. Final judgment means the case would be completed at the trial court level and appealable; no trial date has been set yet for Pavia v. NCAA, with the two sides suggesting trial dates to Campbell ranging from June 2026 to February 2027.

Pavia’s group desires for former JUCO football players to be able to compete in D-I “without regard to years of eligibility or seasons of competition at junior colleges.” The NCAA limits eligibility in one sport to four seasons of intercollegiate competition—including JUCO and D-II competition—within a five-year period. It also generally restricts former JUCO players to three years of D-I football. Pavia has proposed that the D-I eligibility clock begin when a player first registers at an NCAA member school, not when they first register at a “collegiate institution,” which includes non-NCAA schools.

In a related antitrust litigation brought by Pavia’s attorneys, Vanderbilt senior linebacker Langston Patterson is among players suing the NCAA over eligibility rules, and in particular the ones that govern redshirt. Patterson argues that since redshirt players have five years to practice and graduate, there’s no persuasive reason to limit them to four seasons of D-I play. These players seek to expand their maximum number of D-I seasons from four to five. Patterson’s case is before the same judge, Campbell, who is weighing whether to grant a preliminary injunction to authorize a fifth season of play.

Pavia, 23, is a seasoned college football player. He’s playing in his sixth season of college football, with his first two seasons at JUCO New Mexico Military Institute and the last four at New Mexico State and Vanderbilt. Pavia is also one of the best quarterbacks in college football and recently finished second to Indiana’s Fernando Mendoza in the 2025 Heisman Trophy voting. Pavia is earning a great deal as a power conference QB, too. In June, he said he was offered $4-$4.5 million by other colleges to transfer.

Pavia has publicly indicated he intends to participate in the 2026 NFL draft. With more than two dozen other former JUCO players as co-plaintiffs, the case brought by Pavia against the NCAA could continue without him. The NFL’s deadline for underclassmen to declare is Jan. 14. If Pavia gains the choice to remain in college, it’s plausible he might stick around.

After all, Pavia’s NFL draft prospects are mixed. Listed at 6-foot and regarded as relatively slight, Pavia would be on the smaller side for an NFL quarterback. Although it is early for draft prognostications and the NFL combine isn’t until February, Pavia is generally regarded as a late-round draft pick or priority free agent. He also doesn’t project as a likely NFL starter, at least early in his NFL career. Those outlooks have financial implications. A sixth-round pick will sign a four-year contract worth in the ballpark of $4 million. With NIL and House settlement revenue share, Pavia could probably earn more, and potentially much more, by staying in college and dominating.

Last year at around this time, Campbell granted Pavia a preliminary injunction to play in 2025. Shortly thereafter, the NCAA issued a one-time waiver for the 2025–26 academic year that allowed qualified former JUCO players the chance to remain in school. Since that time, more than three dozen “Pavia lawsuits” have been filed by former JUCO and Division II players who want to keep playing in college. Also, in October, a three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit on Wednesday dismissed as moot the NCAA’s appeal of Campbell’s order on grounds that Pavia was already playing, and the NCAA had granted a waiver. The Sixth Circuit remanded the case back to Campbell.

In Friday’s court filing, Pavia describes this arrangement as unfair and unlawful under antitrust law. He notes how other categories of relatively older players receive five years of eligibility to play four seasons, a longer window than ex-JUCO players. Those categories include:

• A player who graduates from high school, then plays football at a prep school for a post-grad year before joining a D-I college.

• A player who plays another professional sport (Chris Weinke became a football player at Florida State in 1997 as a 25-year-old after a six-year pro baseball career).

• As of 2025, the NCAA allows former pro basketball players to play college basketball even though they are former pros in the G League and Europe. As noted by Pavia, former NBA draft pick James Nnaji, who grew up in Nigeria and has played professionally in Europe but not in an NBA regular season game, will soon join Baylor’s men’s basketball team. Sportico examined the topic of pro basketball players joining NCAA teams and its impact on Pavia v. NCAA in depth last summer.

Pavia insists that if the NCAA was worried about the impact that he and other seasoned college players have on competitive balance, “it would preclude other older athletes from competing in Division I NCAA sports.”

The antitrust argument leveled by Pavia depicts the NCAA and its member schools and conferences as engaging in a group boycott of former JUCO football players. By limiting how long these players can play D-I, those players are denied potential NIL and revenue-share compensation. Pavia’s expert witness, Dr. Joel Maxcy, is quoted as saying NCAA member schools enjoy a “financial advantage by moving older players out and replacing them with younger players,” since “an outgoing star would be considerably more costly to the school than an incoming player.”

The underlying logic is that football players of Pavia’s caliber, experience and fame can demand more in compensation from colleges than a teenage high school student who might not play a featured role in college until his sophomore or junior year. Pavia says by pushing “older, more experienced players” out of NCAA football, “schools will have the ability to bring in additional freshmen at a much lower cost.”

As Pavia tells it, D-I college football players constitute a labor market, meaning a group of players who seek to sell their (relatively) elite football services to colleges. Colleges, as competitors to buy players’ services, can run afoul of antitrust law by limiting how they compete.

To advance that point, Pavia draws extensively from former Ohio State football star Maurice Clarett’s antitrust litigation against the NFL. Clarett challenged an eligibility rule that requires players be three years out of high school. As a disclosure, I was one of the attorneys representing Clarett in the litigation.

Clarett argued that the relevant market for his case was the market for NFL players, with NFL teams as the buyer of players’ services. That market is distinct and there are no reasonable substitutes; no one would credibly say the XFL, UFL, CFL, AAF or any other non-NFL pro league is a credible substitute. Pavia analogizes that point to say that the market for his services is D-I football, especially since “more than 99% of NIL dollars are paid to those athletes.” Neither playing in JUCO nor playing in the NFL is a substitute to D-I football, Pavia insists. He cites data showing how “less than 1% of Division I football players get drafted into the NFL each year.”

An NCAA spokesperson responded to a request for comment on Pavia’s latest court filing by providing context on the Nnaji eligibility decision. As discussed above, Pavia contends the NCAA allowing Nnaji and other former pro basketball players to play D-I undercuts the association’s justification to limit the number of eligible seasons.

“Each eligibility case is evaluated and decided individually based on the facts presented,” the spokesperson said in a statement. “Schools continue to recruit and enroll individuals with professional playing experience, which NCAA rules allow with parameters.”

The spokesperson added that “as NCAA eligibility rules continue to face repeated lawsuits with differing outcomes, these cases are likely to continue, which underscores the importance of our collaboration with Congress to enable the Association to enforce reasonable eligibility standards and preserve opportunities to compete for future high school student-athletes.”

Attorneys for the NCAA will have the opportunity to try to rebut Pavia’s arguments.

Expect NCAA attorneys to argue, as they have in other court filings, that eligibility rules ought to fall outside the scope of antitrust law since they concern how long a college student can play a sport—a primarily educational, rather than economic, matter.

The NCAA will also assert that eligibility rules are designed to link an athlete’s athletic experiences with the normal trajectory of a college student. Usually after four years of college courses, athletes and non-athlete students graduate and move on to another phase of life, usually a job.

In addition, the NCAA will likely maintain that Division I college football is a unique product and the closer it resembles an inferior version of the NFL, the more it will seem like minor league football. Fans, consumers, broadcasters, media and others, so the theory goes, could then tune out.

NIL

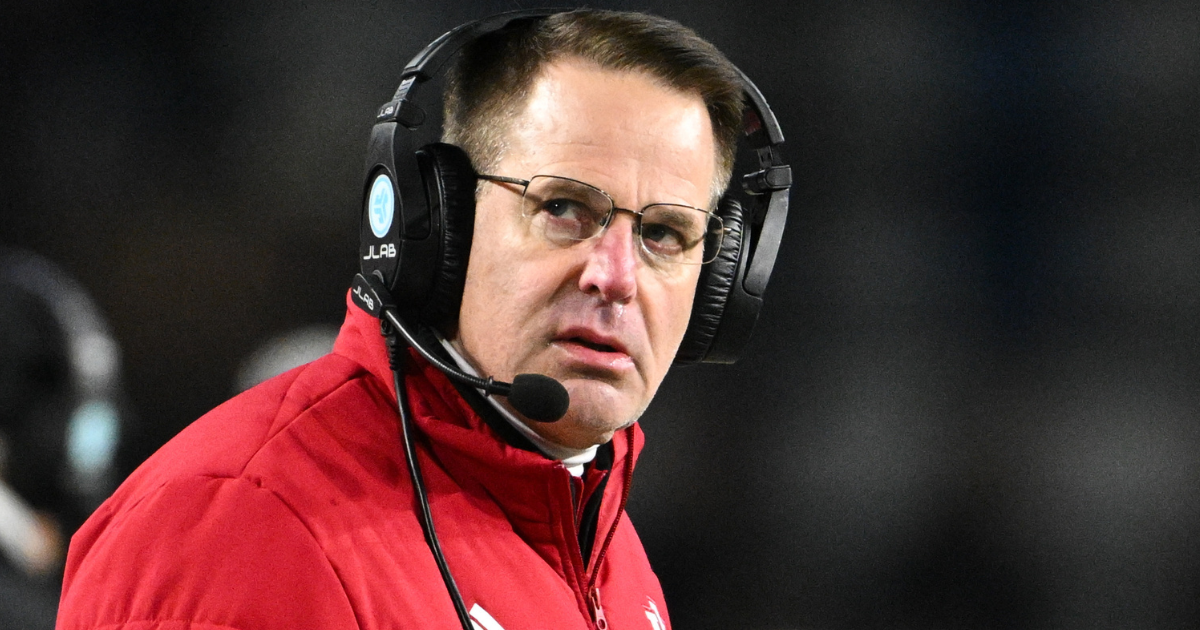

Curt Cignetti expresses frustration with college football calendar amid playoff schedule

The eight teams still remaining in the College Football Playoff are going to see a quick turnaround following their games and the start of the NCAA transfer portal. The quarterfinals will be played on Dec. 31 and Jan. 1, and the portal opens on Jan. 2.

Indiana head coach Curt Cignetti is one of the several head coaches having to deal with CFP fallout, followed by the portal opening a few hours later. Ahead of the Rose Bowl, Cignetti expressed his frustration with the current schedule in college football.

“I definitely think the calendar could be improved,” Cignetti said. “And that would be unanimous amongst the coaches. Whether you got to move the start of the regular season up a week and start playing in the playoffs when the season ends so there’s a little bit better time to devote to high school recruiting and portal recruiting, we’re all looking, I think, for that solution.

“What you’re doing within college football is just you don’t have one guy in charge. If you had one person calling the shots, I think it would be a lot cleaner. So hopefully we’ll make some progress in that regard.”

In the Hoosiers’ case, they have a 4 p.m. ET kickoff vs. Alabama in the Rose Bowl. Regardless of the outcome, the transfer portal opens at midnight for both teams. Either Cignetti, or Alabama head coach Kalen DeBoer, will be dealing with major disappointment after a loss. The other will be starting bowl prep for the national semifinal.

The overlap has shaped the decision-making process in the coaching carousel following the regular season. Three head coaches — Lane Kiffin (Ole Miss–LSU), Jon Sumrall (Tulane–Florida) and Bob Chesney (James Madison–UCLA) –ended up taking their next job before their team played in the College Football Playoff.

Sumrall and Chesney wore two hats during their respective CFP preparation in order to build their staff and maintain recruits in time for the portal to open. Kiffin, who was not allowed to coach Ole Miss in the playoff, has had his sole focus on LSU since being hired earlier this month.

The NCAA transfer portal will be open for 15 days, closing on Jan. 16 — three days before the national championship on Jan. 19. Additionally, the transfer portal is open for five extra days for players competing in the title game.

Cignetti isn’t the first coach to take issue with the current college football schedule this season. That said, if changes aren’t made — he won’t be the last.

NIL

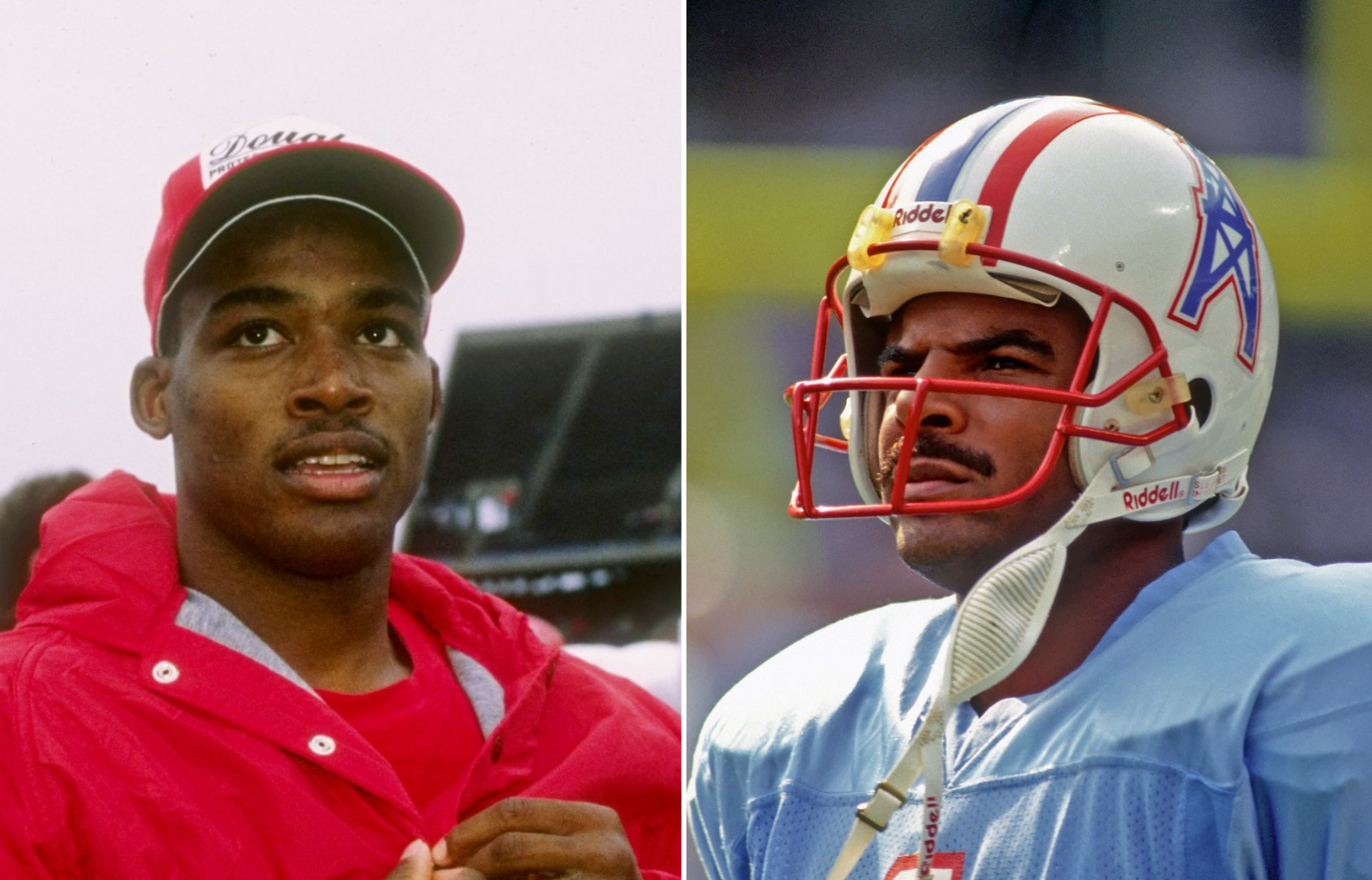

Houston’s most legendary QBs detest this element of modern football

Andre Ware and Warren Moon are two Houston legends with plenty to say on the state of college football.

Both are former quarterbacks who shined in the Bayou City. Both led college and pro football in an assortment of passing stats in the 1980s, helping revolutionize the sport with high-flying, high-scoring offenses. What do the two share in 2025? Frustration with the state of modern college football.

Article continues below this ad

“It’s like the Wild West out there right now,” Moon, a star at Washington in the late-1970s before his 1980s dominance with the Houston Oilers, told Chron this month. “There need to be restrictions on some of the things that are going on right now where it’s not just free-free fall every six months.”

Moon, now 69, played his college games on the west coast at Washington when Pac-8 games were watched by a small fraction of the country each week. Ware had more fanfare as a collegiate player. He took college football by storm in his senior season with the Houston Cougars in 1989, earning the Heisman Trophy with nearly 4,700 yards passing and 46 touchdowns (both NCAA highs) in 11 games.

Ware became a major celebrity in Houston and nationwide in 1989. The Galveston kid became something of a local hero. For Ware, there was no absence of fanfare. But he insists there’s still a crucial difference between his collegiate career and that of many recent Heisman-worthy quarterbacks, who log stints at multiple programs and secure major gains in NIL contracts as a result. Ware says his greatest joy as a quarterback didn’t come from awards or esteem. Rather, a bond with his teammates, forged over multiple years of mutual growth.

Ware didn’t attend the Heisman Trophy ceremony in New York in 1989. Instead, he remained in Houston before a season-finale against Rice, where he famously watched the ceremony with his Houston offensive lineman. Ware insists no amount of NIL money could have poached him from Houston. When a quarterback makes a commitment, he’s obliged to keep it.

Article continues below this ad

“All someone has to do now is open a wallet and a kid will switch,” Ware said. “It’s one of the things coaches always tell me. But if you commit, stay committed. It says a lot about your character.”

Former Houston Cougars quarterback Andre Ware spent his Heisman Trophy ceremony not in New York, but with his offensive linemen in Houston.

Moon admits he isn’t quite so much of a hardliner as his fellow Houston legend. Moon’s career, in some ways, is defined by its winding course. He started his collegiate career at West Los Angeles College before making the leap to major college football at Washington. He won four straight championships in the Canadian Football League from 1978-81, and his NFL career included four franchises from 1984-2000. Moon doesn’t want an overly-strict approach. He just wants to fortify the currently crumbling guardrails.

“I understand why guys end up leaving, but I don’t really like it. I think there should be some more parameters behind it,” Moon said. “Parameters should be put on how much you can move around, if you have to sit out a year after you transfer. … There are plenty of things [the NCAA] can do.

Article continues below this ad

“The old structure wasn’t perfect. It works better than this.”

Warren Moon starred at the University of Washington before starting his winding professional career.

Moon then removes his metaphorical soap box for a moment, offering understanding through a more personal moment of reflection. Moon was a young quarterback once, widely considered one of the top upcoming passers during his time at Washington. “If I was playing today, everything would be different. I would command top dollar,” Moon says.

The actual money is important, of course, but Moon hints at something deeper in the NIL and college compensation game these days, especially among top quarterbacks. Just as chasing passing records is a competition, so is the jockeying for contract dollars. That battle was previously waged professionally. It’s now done collegiately, a system Moon and Ware can understand given their own superstar journeys.

Article continues below this ad

“If I was the same type of caliber player today as I was back then, yeah, I’d be a big time earner,” Moon says. “I’d be at the top with just about any other player.”

NIL

Can UW Sports Compete In Division I As Lower Divisions Offer More NIL Money?

Scott Ortiz watched from the stands at War Memorial Stadium on Nov. 22 as the University of Wyoming Cowboys faced Nevada in what should have been a season-defining moment for the school’s football program.

The atmosphere was electric — one of the most charged Ortiz had experienced since star quarterback Josh Allen was slinging passes for the Brown and Gold.

The crowd roared.

The energy crackled through the crisp November air.

On the field, however, the Cowboys couldn’t convert when it mattered.

“You’re watching the game and you’re realizing that if we had money to spend at certain skill positions, we could easily convert these third downs, we could keep drives alive, and we just don’t,” Ortiz told Cowboy State Daily. “Our inability to move the ball to score in that electric atmosphere was just painful.”

The 13-7 loss to Nevada was only the beginning.

Wyoming went on to score just seven points total in its final four games — a stunning collapse that left the Cowboys out of bowl eligibility and left the Casper attorney and longtime UW booster convinced that without action, Wyoming athletics faces an existential crisis.

The Pokes’ dismal end to the 2025 season kept them out of a bowl game.

Now in the heart of football bowl season and the college football playoffs, sports fans around Wyoming will continue to debate how best to shape the future of UW football.

Should UW do all it can to pay for the best players in an effort to climb the totem pole of television ratings and one day contend for a playoff berth in big-time Division I competition?

Or should Wyoming go the way of Saint Francis University, one of a growing number of schools voluntarily dropping out of the rat race for TV revenue and voluntarily leaving the Division 1 ranks?

College Is Pro

Chase Horsley has watched college athletics transform from his perch at “The 5 Horsemen” podcast in Gillette, where he covers Wyoming sports for Horseman Broadcasting and Entertainment.

“Nothing is the same anymore,” Horsley told Cowboy State Daily. “It kind of feels like more of the NFL type of thing.”

The NIL era of paying players has created a new reality where talent flows toward money.

Horsley sees it affecting Wyoming’s ability to keep homegrown talent and recruit out-of-state prospects to choose UW. Then there’s the challenge of keeping talented players from being lured away by other universities with larger NIL war chests.

“The Wyoming kids aren’t really trying to go to the University of Wyoming,” Horsley said. “Some of them are going, some of them aren’t going.”

The lure is obvious.

“Would you not want to go play if you’re going to get paid, like, a million bucks or $500,000?” Horsley asked. “I mean, we’ve got college kids that are getting out of college and are millionaires.”

For Ortiz, the comparison to schools within Wyoming’s own competitive tier is damning.

Research shows that Montana and Montana State — schools competing in the Football Championship Subdivision, a tier below Wyoming’s Football Bowl Subdivision — are spending about $2.2 million on NIL, while Wyoming hovers around $1.4 million.

“Isn’t that shockingly embarrassing to think about?” Ortiz said. “Schools that don’t sit on the wealth of money we do are outspending us.”

Ortiz said he’s speaking with legislators about tapping into a tiny fraction of the state’s mineral-wealth rainy day fund to help back UW athletics.

He points to what he considers a wake-up call from neighboring Utah: Brigham Young University reportedly paying $7 million to one basketball player.

Left Behind

Not everyone in Wyoming is convinced the answer is more spending. Some voices have quietly suggested the Cowboys consider stepping down in the Division I ranks and from FBS competition entirely.

Alan Stuber, a Gillette Police Department patrol officer and lifelong Wyoming fan who wrestled collegiately at Dakota Wesleyan, has heard the arguments.

“There’s always been an argument of, ‘Well, why don’t we just go to the Big Sky (Conference) and kind of deal with the South Dakota States,'” Stuber told Cowboy State Daily. “Their football program is very successful year after year at making the (FCS) playoffs.”

But Stuber rejects that reasoning.

“In my mind, it’s still a step down,” he said. “Those are the schools that have the least amount of NIL money. So they’re going to be content where they’re at.”

Stuber points to the career trajectory of former Wyoming head coach Craig Bohl as evidence of Division I’s value.

“If it wasn’t such a big deal to be a D-1 college, why did Coach Bohl make the move from North Dakota State to Wyoming?” Stuber asked.

For Stuber, the choice is binary: “You either roll with the changes or get left behind. And I feel that Wyoming is kind of on that verge of getting left behind.”

Cautious Dissent

One Laramie resident who contacted Cowboy State Daily took the opposite view, arguing Wyoming should follow the lead of Saint Francis University in Pennsylvania, which announced in March it would transition from Division I to Division III.

“That is exactly what Wyoming should do,” the reader wrote, suggesting the university examine “the zero athletic scholarship Division III” model or even “club sports.”

The reader, who asked to remain anonymous, explained the reason for his reluctance to go public.

“I do not wish to stimulate even more harassment or other adverse actions from the university’s administration by being made part of this story,” he wrote.

Saint Francis is part of a small but growing list of schools reconsidering their Division I commitments. The University of Hartford completed its transition from D-I to D-III in September 2025.

Another St. Francis — St. Francis College in Brooklyn — eliminated all athletics programs entirely in 2023. Sonoma State University in California cut all 11 intercollegiate athletic programs in January 2025.

But such moves remain the exception.

Before 2025, only two schools in the previous quarter-century had voluntarily dropped from Division I to Division III: Centenary College in Louisiana (2009) and Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama (2006).

Begging To Get In

UW Athletic Director Tom Burman offered a pointed rebuttal to those suggesting Wyoming consider the FCS route.

“The better question is, why are Montana, Montana State begging to get into the Mountain West?” Burman told Cowboy State Daily. “I can tell you that the top tier of the FCS is willing to pay money to join the Mountain West.”

Horsley, despite his concerns about NIL pressures, agrees that dropping down would be a mistake.

“I think they would do well with the Big Sky,” Horsley said. “But I think revenue-wise and like booster clubs, things like that, I think they would want to just keep D-1 and in the FBS.”

The financial gap between the two levels remains substantial.

Mountain West schools receive about $3.5 million annually from the conference’s television deal with CBS and Fox — a six-year, $270 million agreement running through 2025-26, according to The Associated Press.

The Big Sky Conference’s ESPN deal, while recently extended through 2029-30, does not publicly disclose per-school distributions, though Big Sky Commissioner Tom Wistrcill has said the new contract includes a “very nice increase in dollars.”

New upstart members like Utah Tech have agreed to receive no media revenue until 2030-31, according to membership agreements obtained through public records requests by the sports website Hero Sports.

Total athletic department budgets tell a similar story.

Wyoming’s annual budget sits around $50 million, according to NCAA financial reports compiled by USA Today.

In the Big Sky, budgets range from Sacramento State’s $35.8 million down to Idaho State’s $12.1 million, with Montana and Idaho around $22-23 million, according to the USA Today database.

Yet on NIL specifically, the picture is more complicated.

Montana’s estimated $2.2 million in collective spending actually exceeds Wyoming’s, according to NIL tracking data compiled by nil-ncaa.com, placing it ahead of even some Big 12 teams in the NIL arms race.

“We struggled from the time NIL started really in ’22 until the end of June this past year,” Burman said. “We struggled getting people — Wyoming fans, alumni, donors — to invest in the collective.

“It’s just not something Wyoming people embraced.”

At A Crossroads

For Ortiz, the stakes extend beyond wins and losses. He sees Wyoming at a historical crossroads, comparing the current moment to the program’s darkest chapter.

“We are now at probably the biggest low point since the Black 14 in 1970,” Ortiz said.

The Black 14 incident actually happened in October 1969, when 14 Black players planned to wear black armbands during an upcoming game against Brigham Young University.

They sought to protest the LDS Church’s policy barring Black men from the priesthood, amid broader racial tensions that included racist taunts directed at Wyoming’s Black players during BYU games.

When the players approached head coach Lloyd Eaton for permission, he expelled them on the spot, citing team rules against demonstrations.

“It took Wyoming a decade to recover from that when they lost all those players,” Ortiz said. “And I see this as exponentially more dangerous.”

Without action, Ortiz fears a spiral that could fundamentally alter Wyoming’s place in college athletics.

“Once people say, ‘OK, you’re on a losing slide anyway, and you’re not an exciting team, and you’ve already been passed over to go to a better conference, and you don’t have any money to pay us anyway’ — I mean, we could become the doormat of the Mountain West,” he said. “Or worse.”

Does worse mean dropping down to the Big Sky Conference?

“Maybe the Big Sky doesn’t want us,” Ortiz said. “Maybe we’re in a league with Chadron State. From an enrollment standpoint, there’s a lot of Division II and Division III schools that have the same enrollment as Laramie does.”

He warns those calling for self-relegation that, “You literally might as well say, ‘Fine, we’ll just be a rodeo school and have a good science department.’”

Contact David Madison at david@cowboystatedaily.com

David Madison can be reached at david@cowboystatedaily.com.

NIL

Texas RB Quintrevion ‘Tre’ Wisner plans to enter the NCAA Transfer Portal

Texas running back Quintrevion Wisner plans to enter the NCAA Transfer Portal, according to On3’s Pete Nakos. Wisner’s agent Grayson Sheena of AiC.Sports confirmed the decision to Nakos.

Wisner has spent the past three seasons at Texas, where he’s rushed for 1,734 yards on 369 carries, averaging 45.6 yards per game, with 20 starts in 38 career games in Austin. He’s also caught 66 passes for 457 yards and two more scores.

After appearing mostly on special teams as a freshman, Wisner broke out over the past two seasons as the Longhorns’ leading rusher, posting 357 carries for 1,661 yards, averaging 69.2 per game and 4.7 per rush, with eight touchdowns along with all of his receiving production.

Following a breakout sophomore season where he earned a place on the All-SEC third-team with 1,375 yards from scrimmage, including 1,064 rushing yards and six total touchdowns, Wisner struggled through a difficult junior season this past year. Appearing in nine games, Wisner managed just 597 rushing yards and three scores on the ground in 2025.

A native of Glenn Heights (Texas), Wisner played his high school football at DeSoto, where he was a Top-450 overall recruit as a three-star prospect in the 2023 recruiting cycle. He also rated as the No. 30 RB in the class and just inside the Top-75 of players that year coming out of the state of Texas. That’s according to Rivals’ Industry Ranking, a weighted average that utilizes all four major recruiting media companies.

This transfer news comes as Texas is preparing to play Michigan in the Citrus Bowl on New Year’s Eve. With Wisner’s departure, the Longhorns lose their top two running backs from this fall after CJ Baxter also revealed plans to enter back on December 8th. Those, along with the others so far, will then become official once the one-time portal window opens on Jan. 2nd.

Wisner has been a key part of the offense the last two seasons for Texas. He, however, will be spending his final season of eligibility elsewhere, with him intending to be in once the two-week portal window opens on January 2nd.

To keep up with the latest players on the move, check out On3’s Transfer Portal wire.

The On3 Transfer Portal Instagram account and Twitter account are excellent resources to stay up to date with the latest moves.

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoSoundGear Named Entitlement Sponsor of Spears CARS Tour Southwest Opener

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoDonny Schatz finds new home for 2026, inks full-time deal with CJB Motorsports – InForum

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoDavid Blitzer, Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment

-

NIL2 weeks ago

NIL2 weeks agoDeSantis Talks College Football, Calls for Reforms to NIL and Transfer Portal · The Floridian

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoRick Ware Racing switching to Chevrolet for 2026

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks ago#11 Volleyball Practices, Then Meets Media Prior to #2 Kentucky Match

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoWearable Gaming Accessories Market Growth Outlook

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoSunoco to sponsor No. 8 Ganassi Honda IndyCar in multi-year deal

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoNASCAR owes $364.7M to teams in antitrust case

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoNascar legal saga ends as 23XI, Front Row secure settlement