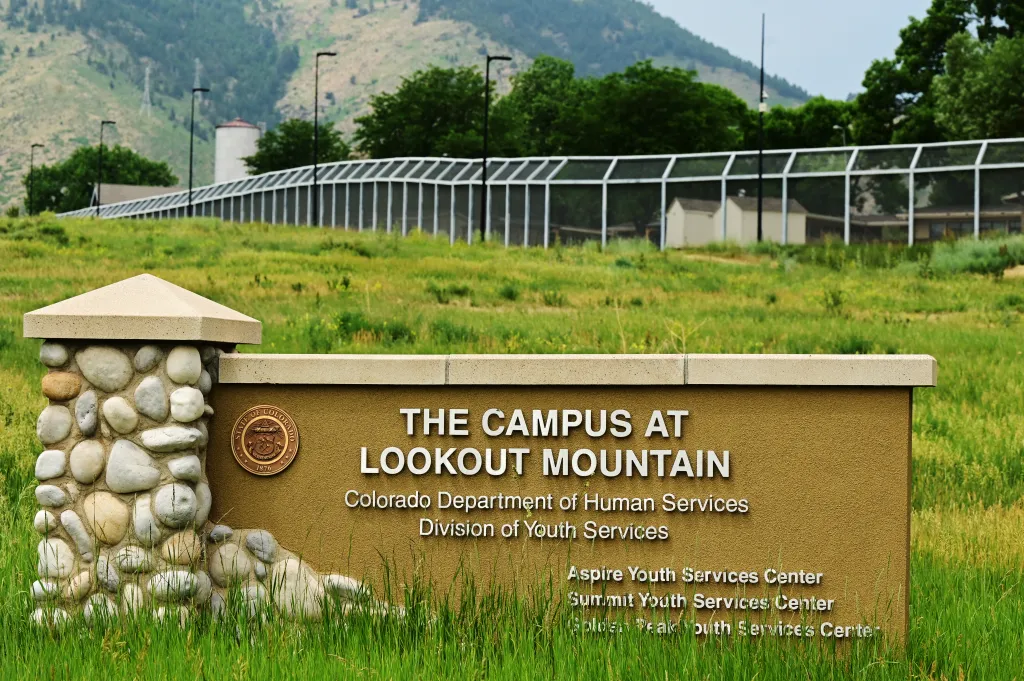

Carissa Wallace started working at the Lookout Mountain Youth Services Center in Golden two years ago because she felt strongly about helping rehabilitate young people convicted of crimes.

She loved the teens and loved the work.

But staffing shortages began to take a toll. Management routinely mandated employees pull 16-hour shifts multiple days a week because they were so short-staffed. Fewer workers meant there was nobody to respond to crises or adequately monitor the young people in their care, she said. Safety concerns mounted.

Wallace said she came home every day and cried. She went to the doctor for medication to help deal with all the anxiety the job brought.

“After two years, I was mentally broken from that place,” she said in an interview. “When I had to think about my safety every second of the day, I could no longer make a difference. I could no longer help the kids.”

Colorado’s youth detention centers are facing a staffing crisis, leading to serious safety concerns for employees and youth and low worker morale, current and former staffers told The Denver Post. The Division of Youth Services, which oversees the state’s 12 detention and commitment facilities, employs more than 1,000 employees, according to state data. Nearly 500 additional jobs remain vacant.

Some facilities, such as the Mount View Youth Services Center in Lakewood, reported a 57% staff vacancy rate, according to June figures compiled by the state. At the Spring Creek Youth Services Center in Colorado Springs, nearly 10% of its staff at one point in November were out due to injuries sustained on the job.

Current and former staff say leadership deserves a large chunk of the blame. Employees say they don’t feel management supports them or listens to their concerns. Higher-ups aren’t on the floor dealing with riots, they say, or leading programs. When situations do get out of control, staff say the brass simply looks for someone to blame.

“The administration says they care,” said Kim Espinoza, a former Lookout Mountain staffer, “but their actions say otherwise.”

Alex Stojsavljevic, the Division of Youth Services’ new director, acknowledged in an interview that working in youth detention is difficult. Retaining staff is a big priority with ample opportunities for improvement, he said. The division plans to be intentional about the people it hires into these roles, making sure that candidates know what they’re signing up for.

He hopes to sell a vision that one can make youth corrections a long, fulfilling career.

“Change is afoot in our department,” said Stojsavljevic, who took the mantle in October. “Just because we’ve done something for 20 or 30 years doesn’t mean we have to continue to do it that way.”

Critical staffing levels

Staffing shortages at Colorado prisons and youth centers have remained a persistent problem in recent years, though vacancy rates at the DYS facilities far outpace those at the state’s adult prisons.

A lack of adequate employees means adult inmates can’t access essential services like medical, dental and mental health care, according to a 2024 report from the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition. Education, employment and treatment programs lag.

“Simply put, because of the staff shortage, the (Department of Corrections) is not able to fulfill its organizational mission, responsibilities and constitutional mandates,” the report’s authors wrote.

Studies point to a litany of physical and mental health issues facing corrections workers.

Custody staff have a post-traumatic stress disorder rate of 34%, 10 times higher than the national average, according to One Voice United, a national organization of corrections officers. The average life expectancy for a corrections worker is 60, compared to 75 for the general population. Divorce and substance abuse rates are higher than in any other public safety profession, the organization noted, while suicide rates are double that of police officers.

The Colorado Department of Corrections has a 12.6% overall department vacancy rate, according to state figures. Correctional officer vacancies sit at 11%, while clinical and medical staff openings are nearly 20%.

Meanwhile, nearly one in three DYS positions is vacant.

The most common open positions are for the lowest level correctional workers, called youth services specialists. The Betty. K. Marler Youth Services Center in Lakewood currently has 23 vacant positions for this classification of employee out of 63 total slots. The facility is also short 10 teachers. Platte Valley Youth Services Center in Greeley has 21 open positions for the lowest-tier youth services specialist role out of 71 total jobs.

The same candidates who might work at DYS are also being recruited by adult corrections, public safety departments and behavioral health employers, Stojsavljevic said, leading to fierce competition for these applicants.

Current and former DYS workers say the staffing issues serve as a vicious cycle: The fewer employees there are, the more mandated overtime and extra shifts that the current staff are forced to take on. Those people, then, quickly burn out from the long hours and dangerous working conditions, they say.

Wallace, the former Lookout Mountain worker, said almost every day for the past year, leadership mandated staff stay late or work double shifts. This routinely meant working 16-hour days.

“It got to the point where people weren’t answering their phones,” she said. “People were calling out sick because they were overworked and exhausted.”

Wallace estimated that 80% of the time, the facility operated at critical staffing levels or below. State law requires juvenile detention facilities to have one staff member for every eight teens, but workers say that wasn’t always the case.

Many days, staffers said, there weren’t enough employees to respond to emergencies. In some cases, that meant the young men themselves assisted staff in breaking up fights with their peers.

One night, some of the teens set off the fire alarm at Lookout Mountain, which unlocked the doors and allowed the young people to run around campus, climb on buildings and break windows, workers said. Without enough staff to rein in the chaos, employees wanted to call 911.

But they said they were told they would be fired if they did. Leadership, they learned, didn’t want it covered by the press.

“Our jobs, our lives were threatened because they didn’t want media coverage,” Espinoza said.

Stojsavljevic said the department is “acutely aware” of the mandated work problem, though he admitted that in 24-hour facilities, staff will occasionally be told to work certain shifts.

The division has implemented a volunteer sign-up list, where staff can earn additional incentives for working these extra shifts.

Since he’s been in the job, the state’s juvenile facilities have never dropped below minimum staffing standards, Stojsavljevic said.

Routine violence in DYS facilities

Staff say violence is an almost daily occurrence inside DYS facilities, which contributes to poor staff retention.

The division, since Jan. 1, recorded 35 fights and 94 assaults at the Lookout Mountain complex, The Post reported in September. Since March 1, police officers have responded 77 times to the Golden campus for a variety of calls, including assaults on youth and staff, sexual assault, riots, criminal mischief and contraband, Golden Police Department records show.

Twenty of these cases concerned assaults on staff by youth in their care.

Multiple employees suffered concussions after being punched repeatedly in the head, the reports detailed. Others were spit on, bitten, placed in headlocks and verbally threatened with violence.

Chaz Chapman, a former Lookout Mountain worker, previously told The Post that he reported three or four assaults to police during his tenure, adding, “I was expecting to get jumped every day.”

“We were basically never able to handle situations physically, and the kids knew that; they were stronger than 90% of their staff,” Chapman told The Post in September. “The ones who stood in their way would get assaulted, such as myself.”

Staff said leadership still expected them to show up to work, even while injured.

Espinoza said she injured her knee during a restraint, requiring crutches. DYS continued to put her on the schedule, she said. So the staffer hobbled around the large Golden campus through the snow and ice.

One supervisor had his head cracked open at work this year, Espinoza said. He went to the hospital and returned to Lookout. Wallace said she’s been to the doctor 20 times since she started the job due to injuries sustained at work. She said she still has long-lasting shoulder pain.

“If they’re gonna keep hiring women who can’t restrain teenage boys, people are going to get hurt,” she said. “That was an everyday thing.”

In November, 28 DYS employees were out of work on injury leave, according to data provided by the state. Spring Creek Youth Services Center in Colorado Springs had nine workers injured out of 91 total staff. The state did not divulge how these people were hurt.

Stojsavljevic said safety is the division’s No. 1 focus area. If staff are injured on the job, he said, it’s important that they’re supported.

“Staff have to be both physically healthy and emotionally healthy to do this work,” the director said.

Division policies allow injured employees to take leave if they need it. Depending on the level of injury, some staff can return to work without having youth contact, Stojsavljevic said.

‘That place takes your soul’

But workers interviewed by The Post overwhelmingly blamed management for the division’s poor staffing levels.

As staff worked 16-hour days and were mandated to come in on their days off, they said administrators wouldn’t pitch in.

“A lot of people felt it’s unfair,” Wallace said. “The people making a good amount of money weren’t truly being leaders. They were forcing us to pick up the slack, but they didn’t want to deal with youth. They wanted to sit at a desk, collect their check, and go home for the day.”

New recruits were thrown into the deep end with barely any training or support, employees said. Those new staffers quickly saw the grueling hours and how tired their coworkers were all the time. Many left within weeks of starting the gig.

“I could see their souls were literally gone,” Wallace said. “That place takes your soul.”

After safety, Stojsavljevic said the department is prioritizing quality and innovation. Leadership wants to make sure that programs and policies are actually getting better results.

The director, meanwhile, said he wants to hear directly from staff for new ideas.

“We’re more than willing to try things out,” he said. “We can’t just continue operations the way they have been just because that’s the way we’ve always done it.”

Wallace said her experience at Lookout Mountain traumatized her. The job prompted her to go to therapy and to start taking medication for anxiety.

When state officials emptied Lookout Mountain due to deteriorating safety conditions in August, Wallace was sent to work at Platte Valley. Leadership promised to retrain staff so they could eventually reopen the Golden campus.

But when Wallace showed up on her first day of work at Platte Valley, security never checked her for contraband, she said. Staff were being mandated to work overtime shifts. Within 20 minutes of starting, she was put alone with a young person she didn’t know.

The following day, Wallace called her boss. She couldn’t work for DYS anymore.

At the end of the day, Wallace said, it’s the young people who suffer.

“I hope they make some changes because these boys deserve so much better than what they’re getting,” she said.

Sign up to get crime news sent straight to your inbox each day.