It’s a regular season rematch with a national championship on the line.

Sports

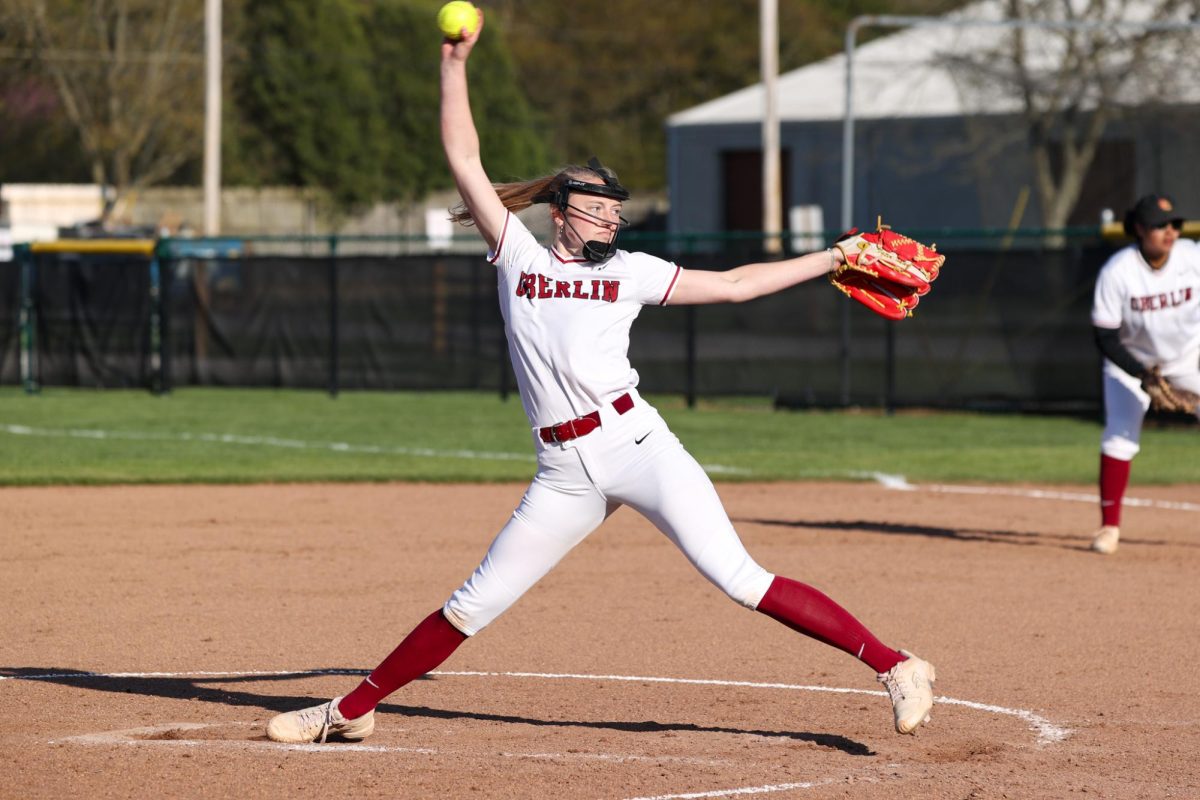

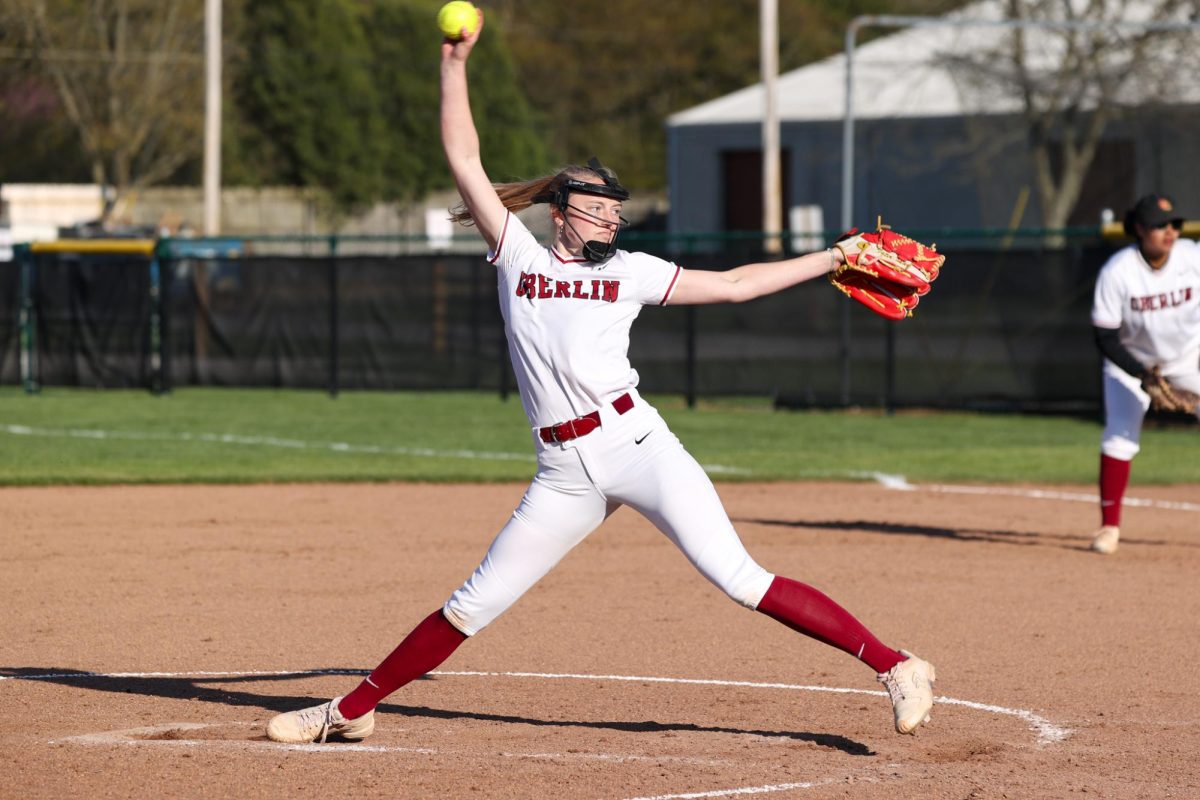

She's Softball's First $1 Million Pitcher—and She Could Be the Last

The Texas Tech softball team is just two wins away from the Women’s College World Series for one spectacular reason.

It has a pitcher worth $1 million.

That’s not hyperbole. Texas Tech’s booster collective actually paid NiJaree Canady a cool million to transfer from Stanford, where she was already a star, and suit up for the Red Raiders this season.

And it looks like money well spent. Canady is responsible for 58% of Texas Tech’s wins. She has posted 28 wins against just five losses and struck out 272 batters over 191 innings pitched through Tuesday.

“She’s one of the top women athletes, so in my mind she deserved what some of those male athletes are getting,” said Tracy Sellers, who funded an endorsement from the school’s donor collective with her husband, John, a former Red Raiders defensive lineman. “I hope it’s setting the stage for the next girl.”

But athletes like Canady are suddenly an endangered species. That’s because a new set of rules that would severely restrict how much boosters can pay college athletes is likely to be enacted in the coming days. The ripple effect could mean fewer softball players, golfers, sprinters and other athletes from lower-profile sports earning big paydays.

If and when Judge Claudia Wilken approves a settlement to a consolidation of three antitrust lawsuits brought by athletes against the major conferences and the NCAA, two big shifts are set to take place. First, each college athletic department will be allowed to share about $20 million of its annual revenues with athletes. But roughly 90% of that money is expected to go to the marquee sports of football and men’s basketball—leaving scraps for sports like softball.

Second, outside deals for athletes to profit from their name, image or likeness (NIL) would begin to go through a new clearinghouse overseen by Deloitte.

In that clearinghouse, deals by major companies like Nike or State Farm are likely to pass muster, said someone familiar with a committee set up by the Power 5 conferences and NCAA to implement the settlement. Deals like Canady’s, funded primarily by booster collectives, are not.

“Booster deals are going to be more difficult to pass,” the person familiar said, adding: “The system is set up to not allow third parties to pay for play.”

After Canady’s sophomore season at Stanford last year, the pitcher entered the transfer portal, where a handful of powerhouse schools lined up to woo her. But it was the last place she visited—Lubbock, Texas—that won Canady over.

The key piece of her move was an endorsement deal from the donor collective known as the Matador Club, worth just over $1 million.

Since the Sellers became billionaires by flipping oil and gas leases in West Texas’s Permian Basin, they’ve donated handsomely to their alma mater. The couple gave $11 million to Texas Tech athletics in 2022, including $1 million for softball facility upgrades.

Canady had six-figure offers from other schools, but nothing close to what the Matador Club offered. But John Sellers, who described himself as a “ready, fire, aim” kind of guy, wanted to make a statement.

But donors like the Sellers could soon become much less influential. That is down to college sports’ continued resistance to characterizing athletes as employees, a move that would require a slew of new rights and regulations.

“I think if people/donors want to invest in sports, specifically Olympic and female sports, they should be given that opportunity,” Canady said. “Oftentimes athletes in these sports don’t really have opportunities to make life-changing deals after college.”

The NIL clearinghouse won’t preclude athletes like Canady from signing endorsement deals, but it will bring considerably more oversight. The organization will want to know, for instance, how a booster club can get $1 million of value in marketing from a player with a profile like Canady, who has 34,000 followers on Instagram but is hardly a household name.

Colleges’ pot of revenue-sharing money won’t be subject to such scrutiny, meanwhile, as long as schools stay under the $20.5 million limit. So an offensive lineman, anonymous as he may be, could receive $1 million directly from his school. But a star lacrosse player would be hard-pressed to gain approval for a $1 million outside of an NIL deal bankrolled by a wealthy alum.

Some in college sports say nixing such deals risks pushing booster money back under the table—where it was for decades.

For the moment, before the settlement is approved, athletes and booster collectives are scrambling to cut deals under the old regulations. The Matador Club has already signed Canady to a one-year extension worth another $1 million, according to a person familiar with the deal.

“Until we figure out exactly what they’re going to let go on,” Tracy Sellers said, “why not keep going?”

Write to Rachel Bachman at Rachel.Bachman@wsj.com and Laine Higgins at laine.higgins@wsj.com

Sports

Street Fighters Club hosts winter health event

Srinagar, Dec 21:Street Fighters Club successfully organised its annual felicitation programme titled “AAMADAY CHILLAI KALAAN” at the Auditorium of Green Valley Educational Institute, Ellahi Bagh, Buchpora. The event witnessed an impressive gathering of athletes, students, health professionals, educators, and community members.

The programme was aimed at spreading awareness about health issues during the harsh winter season while also focusing on reconnecting Gen Z with their cultural roots, especially the rich Kashmiri traditions associated with Chillai Kalaan.

The event commenced with Tilawat-e-Quran, followed by Naat-e-Rasool ﷺ, setting a spiritually enriching tone. In his welcome address, the organisers highlighted the importance of holistic well-being, cultural identity, and community participation.

Renowned medical professionals addressed the gathering, with Dr. Naveed Nazir Shah delivering an informative talk on respiratory issues prevalent during winters, while Dr. Manzoor Ahmad Wani spoke on gut health and healthy food habits, emphasizing lifestyle modifications during extreme cold conditions.

A special address on fitness and healthy living was delivered by Mr. Riyaz Ahmad Kathjoo, Principal, Green Valley Educational Institute, who appreciated the efforts of Street Fighters Club in promoting health awareness and sports culture among youth.

Speaking on the occasion, Mr. Sajad Mir, President, Street Fighters Club, said that AAMADAY CHILLAI KALAAN is not merely an event but a movement to promote physical fitness, preventive healthcare, and cultural consciousness during the most challenging winter period. He reiterated the club’s commitment to community health, youth engagement, and environmental responsibility.

Coach Abid Amin, while interacting with participants, stressed the importance of maintaining physical activity even during extreme winters and encouraged young athletes to stay disciplined, resilient, and rooted in traditional values.

The programme concluded with a felicitation ceremony, where adventure enthusiasts, athletes, and contributors were honoured for their dedication and achievements. The organisers expressed gratitude to Green Valley Educational Institute for their support and hospitality, making the event a grand success.

Sports

Texas A&M volleyball vs Kentucky game score: Live updates

No. 3 seed Texas A&M volleyball faces No. 1 Kentucky in the NCAA Tournament finals and it is the first time two SEC teams will meet at the net for the title.

Article continues below this ad

Texas A&M middle blocker Morgan Perkins (21) celebrates a score during the NCAA Division I volleyball playoff game against TCU at Reed Arena on Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025 in College Station, Texas.

The Aggies have made history in the tournament after upsetting No. 1 seeds (Pitt and Nebraska) and a No. 2 seed (Louisville). The Wildcats narrowly escaped their five set match Thursday against Wisconsin in the semifinal match.

A&M (28-4) lost to Kentucky 3-1 during conference play Oct. 8. (To the Aggies’ credit, they were the first team in SEC play to win a set against Kentucky, in the Wildcats’ fourth conference game.) A&M head coach Jamie Morrison said he was disappointed that the Aggies couldn’t push the eventual SEC champions to five sets, but outside hitter Logan Lednicky said that match showed glimpses of what the Aggies can be.

If Kentucky (30-2) wins, it will be its first national championship since the 2020 season. If A&M wins, it will be the first national title in volleyball for the Aggies.

Article continues below this ad

MORE: Jamie Morrison named AVCA coach of the year after leading Texas A&M to historic run

MORE: Preview of first all-SEC NCAA Tournament volleyball title game

Follow along for live updates of the national championship match.

Article continues below this ad

Texas A&M vs Kentucky score: National championship live updates

Set 2: Texas A&M 15, Kentucky 7

Kentucky comes out of the timeout and is called for a back row attack. But the Wildcats get the crosscourt kill and tool the block to go on a 2-0 run. The Wildcats are setting the ball tightly and are making out of system attack errors at the net. Lednicky gets the crosscourt kill. A Wildcat overpass leads to another Cos-Okpalla kill, her fourth so far. Kentucky calls another timeout.

Set 2: Texas A&M 10, Kentucky 5

Kentucky swings through the A&M block. Perkins responds with another monster block to keep the Aggies ahead. An A&M free ball leads to a long kill from Kentucky. Hudson soars out of the back row to make it 8-5 but Kentucky collects its fifth service error of the night. Stowers closes a seam to stuff Kentucky at the net. The Wildcats call a timeout.

Article continues below this ad

Set 2: Texas A&M 6, Kentucky 3

Waak has a quick throw down that is dug into the stands to open the set for the Aggies, but they give it back with a service error to tie the match 1-1. Lednicky swings high after a long rally to take the 2-1 lead, but Stowers’ service error ties the match again. Waak goes back to Lednicky who is one-on-one along the pin and gets the touch. A Kentucky overpass leads to a Lednicky kill over the net. Cos-Okpalla’s service pressure continues the Aggies run with a heavy arm. Perkins explodes out of the middle for a kill.

Set 1: Texas A&M 26, Kentucky 24

Hellmuth goes offsspeed out of the timeout and DeLeye goes too long on a shot down the line for the third tie of the set. A&M is called in the net to break the tie and give set point for Kentucky. Stowers tools the block to tie the match at 24. Cos-Okpalla blocks a Kentucky tap for its first set point. Kentucky called a timeout but Stowers taps it over for the set win.

Article continues below this ad

Set 1: Kentucky 23, Texas A&M 21

Hudson goes down the line for a kill coming out of the timeout, but Kentucky serves an error and follows it up with an attack error to get the Aggies within one. Cos-Okpalla’s attack error puts Kentucky in the redzone first. Waak feeds Lednicky for a high swing off the block. Hudson gets stuffed at the net to put the Aggies in the redzone to tie the match for the first time. Carr’s kill breaks the tie but a Hudson error ties it at 21. Kentucky gives the ball to Carr for a tie-breaking kill and the Wildcats follow it with an ace. Texas A&M calls a timeout.

Set 1: Kentucky 18, Texas A&M 16

After Kentucky’s challenge is not overturned, the Aggies side out to get within five but a service error keeps momentum with the Wildcats. Texas A&M goes on a 2-0 run with its best offense but miscommunication on defense gives Kentucky its five-point lead back. But A&M is starting to click and goes on a 4-0 run thanks to Waak’s service pressure that forces a Kentucky timeout.

Article continues below this ad

Set 1: Kentucky 13, Texas A&M 7

Cos-Okpalla comes out of the timeout with a quick kill from the middle. Kentucky’s middle, Carr, shows off her hot hand at the net, but Wildcat momentum stalls after being called in the net. Kentucky mistakes keep A&M close and Texas A&M is struggling to play cleanly with four attack errors.

Set 1: Kentucky 6, Texas A&M 1

Kentucky starts the match going on a 3-0 run over the Aggies. The Wildcats are have good transition digs and forcing the Aggies to play out of system. Kentucky serves an error to get the Aggies on the board. Lednicky tries to go line but it misses and Cos-Okpalla has a blocking error that misses the other side of the net. Texas A&M calls an early timeout after Hellmuth gets stuffed.

Article continues below this ad

Texas A&M Aggies players rush the court to celebrate winning a semifinal match between the Texas A&M Aggies and Pittsburgh Panthers in the NCAA Tournament on Dec. 18, 2025 at T-Mobile Arena in Kansas City, Mo.

Texas A&M starting rotation

Article continues below this ad

Article continues below this ad

Kentucky starting rotation

Article continues below this ad

Texas A&M volleyball vs Kentucky time, TV info

Article continues below this ad

Where: T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Mo.

Sports

NCAA title live updates, score, highlights

Updated Dec. 21, 2025, 3:12 p.m. CT

The time is here, and it’s winner‑take‑all for the 2025 NCAA Volleyball Championship. It will be an epic matchup between a red‑hot Texas A&M team and the SEC titan, the Kentucky Wildcats.

A&M plays an energetic and aggressive brand of volleyball. Their roster has few weaknesses, and they stand as the most battle‑tested team remaining. They are led by four All‑Americans and AVCA Coach of the Year Jamie Morrison, who has them on a historic run that has never been seen in Aggieland.

The Aggies will face Kentucky for the second time this season after losing to them 3‑1 for their first and only SEC loss of the season. Both history and revenge are on the line Sunday afternoon in Kansas City when the Aggies take the court to battle for the title of the NCAA’s best.

Follow here for all the live updates, scores, and highlights.

Set 1: Texas A&M 26 | Kentucky 24

After being down six points early, the Aggies battled back to win the first set.

Set point A&M, 24-23

Cos-Okpalla gets a block to give A&M their first lead

Set point for Kentucky after a net foul, 23-24

Aggies get in on the net for a foul

Wildcats are the first to 20, but A&M is fighting back, 20-21

Lednicky is starting to get hot and putting pressure on Kentucky

A&M on a 5-0 run closes the gap, 16-18

Ifenna Cos-Okpalla got things started with a big Kill

Kentucky holds a five-point lead and wins the race to 15, 15-10

Kentucky is staying a few steps ahead and attacking the middle of the court, keeping A&M off balance

The Wildcats are the first to 10 in the first set, 10-4

Kentucky is strong at the point of attack and is getting by all the Aggie blocks

Kentucky jumps out to a 5-1 lead in the first set

A few unforced errors by the Aggies and big blocks from the Wildcats have A&M down early in the first set.

Aggie All-Americans

Why not the Aggies?

What channel is the Texas A&M vs Kentucky game on today? Time, TV schedule

- Date: Sunday, December 21

- Start time: 2:30 p.m. CST

- TV Channel: ABC

- Stream: ESPN APP

Texas A&M vs. Kentucky will be broadcast on ABC for the 2025 NCAA National Championship.

Texas A&M vs Kentucky predictions, picks, odds

Odds courtesy of DraftKings as of Saturday, 12/20

- Spread: Kentucky by 1.5

- Moneyline: A&M -105 / Kentucky +115

Prediction: A&M 2 – Kentucky 3

2025 National Championship

Contact/Follow us @AggiesWire on X and like our page on Facebook to follow ongoing coverage of Texas A&M news, notes, and opinions. Follow Jarrett Johnson on X: @whosnextsports1.

Sports

Kentucky Volleyball vs. Texas A&M preview, viewing info, and a prediction

Kentucky Volleyball already knows what it looks like to beat Texas A&M. Back in October, the Cats walked into Reed Arena and handed the Aggies a four-set loss when they were ranked No. 9 in the country.

Now the stakes are just a little bit higher. Twenty-seven straight wins, one more banner on the line, and a rematch against one of the most physical teams in America.

Advertisement

First, a reminder of what happened last time.

Kentucky hit .293 as a team in that win, piling up 63 kills on 157 swings. Eva Hudson exploded for 24 kills on .373 hitting, and Brooklyn DeLeye added 19 kills. Lizzie Carr was almost automatic in the middle, finishing with 11 kills on .588.

The Cats’ sideout numbers told the story. They were at 68% or better in each of the last three sets and closed it out 21–25, 25–22, 25–15, 27–25. Texas A&M hit just .205 and never really found a rhythm once Kentucky’s block settled in.

Can Kentucky’s firepower crack Texas A&M’s huge frontline for a second time?

This time around, Texas A&M is even sharper. The Aggies are 28–4 overall, 14–1 in the SEC (that lone loss is to the Cats), and they do just about everything at a high level. They hit .298 as a team with 14.6 kills per set. Their opponents hit only .187 and average 11.5 kills per set. They control the net with 2.61 blocks per set and are steady in the backcourt with 13.3 digs per set.

Individually, it starts with outside hitter Logan Lednicky and six rotation arm Kyndal Stowers. Lednicky has 456 kills, 4.11 per set, on .312 hitting, and still gives you over 2.6 digs per set with 98 total blocks. Stowers adds 375 kills at 3.5 per set on .281 hitting and 2.26 digs per set, plus 63 blocks. That is a ton of volume and a ton of pressure from the pins.

Advertisement

In the middle, Ifenna Cos-Okpalla and Morgan Perkins are a nightmare at the net. Cos-Okpalla is hitting .430 with 236 kills and a ridiculous 195 total blocks, about 1.7 per set. Perkins is at .420 with 95 blocks of her own. Setter Maddie Waak runs the show with efficient choices, and A&M’s offense rarely beats itself.

The matchup problem is obvious. Texas A&M’s front line will test Kentucky’s ability to terminate in tight windows and stay patient when rallies stretch out. The Aggies are used to winning the block battle and forcing teams into low-efficiency swings.

The good news for Kentucky is that this team is built to hit high-level blocks and has the numbers to prove it. The Cats are hitting .293 on the season with 14.86 kills per set, almost a mirror of A&M’s attack. Opponents are at .188 with 12.35 kills per set.

Kentucky’s firepower is relentless. DeLeye and Hudson are basically co-number one options. DeLeye has 536 kills at 4.62 per set on .284 hitting, plus 2.34 digs per set and 41 total blocks. Hudson has 533 kills at 4.59 per set on .323, 2.38 digs, and 49 blocks. You cannot load up on one without the other punishing you.

Advertisement

In the middle, Carr is the key. She is hitting .349 with 222 kills and 136 total blocks, 1.23 per set. When Carr is winning quicks and closing out on the edges, Kentucky’s defense goes up a level. Around her, Brooke Bultema and Kennedy Washington both hover around .260 hitting and are capable of stealing seams and putting extra stress on Texas A&M’s middles.

The first contact battle might decide everything.

Kentucky side outs best when libero Molly Tuozzo and the backcourt are in rhythm. Tuozzo is at nearly 4 digs per set with 456 total digs and has been nailing in serve receive most of this run. Molly Berezowitz gives them another steady defender and server. If those two control the ball, setter Kassie O’Brien can run her full menu and keep A&M’s block guessing.

O’Brien has 1,244 assists this season, 11.01 per set, and mixes tempo and angles as well as anyone in the country. When she has all three levels available, Kentucky becomes almost impossible to load up against. If she is stuck living on high balls to the pins, Texas A&M’s block has the size to tilt the match back their way.

Advertisement

On the flip side, Kentucky’s serve needs to make Waak uncomfortable. The Cats average 1.21 aces per set with 140 total, but the bigger thing is disruptive serving that drags A&M off the net just enough to let Carr, Washington, and company get hands on Lednicky and Stowers. Kentucky has 282.5 total blocks this year, 2.44 per set, and they just held Wisconsin’s high-powered attack in check by turning the fifth set into a wall. This has to look similar.

Texas A&M’s resume says they can win this match in a lot of ways. They have more than enough offense, they defend with discipline, and they do not hand out free points. But Kentucky has already seen its best shot, has already solved them once, and is playing with the swagger that comes from a 27-match win streak and a miracle comeback against Wisconsin that will live in program lore.

If Kentucky passes at even an average level, keeps its serve in play, and forces Texas A&M to hit into a loaded block over and over, the Cats will have every chance to finish the job.

Advertisement

Win this one, and it is 28 straight, another trophy for the case, and the kind of back-to-back run that redefines what Craig Skinner has built in Lexington.

🗓️ Date: Sunday, Dec. 21

🕐 Time: 3:30 p.m. ET

📺 TV Channel: ABC

📍 Location: T-Mobile Center, Kansas City, Missouri

📱 Online Streaming Through Cable/Satellite: ABC is included in most standard cable and satellite packages. Check your local listings.

Streaming Services: You can stream the game on services that carry local channels, including: Hulu + Live TV, YouTube TV, FuboTV, Sling TV (Orange Plan)

You may also be able to pick up the game over-the-air for free if you are near an ABC affiliate.

Odds: FanDuel has Kentucky favored by 1.5 sets. The Moneyline for Kentucky is -156, and for A&M, it’s +120.

Advertisement

Prediction: Kentucky rides the double-headed monster of Hudson and DeLeye to title number 2, Kentucky in 4 sets.

What say you, BBN? Send us your game prediction in the comments!

Drew Holbrook has been covering the Cats for over 10 years. In his free time he enjoys downtime with his family and Premier League soccer. You can find him on X here. Micah 7:7. #UptheAlbion. Go CATS!

Sports

How to watch NCAA women’s volleyball finals for free: Channel, time for Texas A&M vs. Kentucky

The two best women’s volleyball teams will square off in the national championship match.

Kentucky takes on Texas A&M in the NCAA Division I finals on Sunday, Dec. 21, at the T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Missouri.

The NCAA women’s volleyball finals will air on ABC and can be streamed live on DirecTV Stream (free trial), fuboTV, ESPN+ and other live TV streaming services.

Here’s what you need to know:

What: NCAA Division I women’s volleyball finals

When: Sunday, December 21, 2025

Who, when: Kentucky vs. Texas A&M, 3:30 p.m. ET

Where: T-Mobile Center, Kansas City, Missouri

TV: ABC

Where to watch the NCAA women’s volleyball tournament live and on demand for free

Viewers without cable can watch games live and on demand for free by signing up for the trial offer from DIRECTV or Fubo.

What are the differences between the streaming services?

DIRECTV – Watch live TV from major broadcast and popular cable networks. Enjoy local and national live sports, breaking news and must-see shows the moment they air. Included: unlimited cloud DVR storage space so you can record as many shows as you want and stream them from wherever you go. DTV starts as low as $19.99 per month after a 5-day free trial when you shop their customizable genre packs.

DIRECTV

5-day free trial

Get up to $20 off your first month and enjoy local and national live sports, breaking news and must-see shows.

Free Trial

Fubo – Fubo offers one of the widest selections of channels among live TV streaming services. More than 220 channels, including all the sports and entertainment you love, plus sports add-ons for those niche networks you rely on, and it all starts with a 5-day free trial and $30 off the first month of service.

Fubo

5-day free trial

Stream college sports! with Fubo, and enjoy up to $30 off your first month.

Free Trial

Sling – One of the best deals in live TV streaming at just $45.99/month, offering customizable channel lineups for sports, news and entertainment. Now, Sling adds even more value with passes that let you stream live TV without a subscription: just $4.99 for a day, $9.99 for the weekend or $14.99 for a full week. These one-time payments are perfect if you just want to watch a single show, live game or special event. No commitment, no auto-renewal, just affordable access when you need it.

Here is more about the game from the Lexington Herald-Leader, via the Tribune News Service:

Two days out from the NCAA volleyball national championship match, Texas A&M’s Jamie Morrison issued an affecting truth to his players.

“Thirty-five athletes have the right to practice today,” Morrison said. “And … each one of our athletes is one of those.”

For the first time in the history of the sport, the national title match will feature two Southeastern Conference teams. No. 3 Texas A&M, in its first-ever national championship, and No. 1 Kentucky, in pursuit of its second-ever national title, and first since 2020-21.

It’s a picture that, even 10 years ago, not many would believe. But it’s not at all surprising that the only two head coaches in America still allowed to show up to practice this weekend.

Craig Skinner had turned down a few other head coaching jobs before finally deciding to accept one in 2004 at the University of Kentucky.

Skinner had experienced national recognition within the volleyball landscape at the high school and club levels in Muncie, Indiana, before successful tenures as an assistant coach for Wisconsin, Ball State (on the men’s team) and then finally at Nebraska, where he — under the legendary John Cook — won his first NCAA national championship in the year 2000.

By the end of his four seasons with the Cornhuskers, Skinner had played a role in guiding the program to an overall record of 154-11 and four-straight Big 12 championships.

When UK director of athletics Mitch Barnhart came calling to ask Skinner to lead the Wildcats, now 21 years ago, Skinner felt that it was the best choice he could make.

Ahead of Sunday’s national championship match — Kentucky’s second under Skinner and second in program history — the head coach described himself as the kind of guy who “probably operates a little bit more on feel than others.”

“And when I got here, and Mr. Barnhart picked me up at the airport, I just had a two-hour conversation with him,” Skinner said. “And felt like this is where I belonged. And it was, the people of Kentucky are who I am as a person. And I thought that was pretty easy to sell.”

But the Wildcats hadn’t recorded a winning season for half a decade, nor made the NCAA Tournament since 1993.

Kentucky had won five Southeastern Conference Tournament titles since the league championship’s inception in 1979, but the SEC was nowhere near the heavy-hitting volleyball conference that it’s become. The SEC Tournament quite literally ceased to exist following the 2005 edition.

“Material things don’t motivate me,” Skinner said. “But people and feelings do, and so Kentucky was all about that. And I can buy into hard work and effort and earning things.”

Morrison, passionate about international and Olympic-level volleyball, served as an assistant for the United States Men’s National Volleyball Team in the mid-to-late aughts before taking a job as an assitant for the U.S. Women’s National Team.

During his stints with each, he won three Olympic medals — gold in the 2008 Beijing Olympics with the men’s team, silver in the 2012 London Olympics and bronze in the 2016 Rio Olympics with the women’s team. He remains the head coach of the U.S. Women’s U19 team.

Morrison also helped establish League One Volleyball, a professional league established in 2024, and served as the league’s director of sports performance.

Dating back to 1999, beginning at his alma mater UC Santa Barbara, Morrison also made a slew of women’s collegiate assistant coaching stops, continuing to do so amid his immense success at the Olympic and professional levels — most recently at the University of Texas from 2020-21.

Like Skinner, Morrison’s first head collegiate coaching opportunity came in the form of an SEC program with some national success, but nothing like the heights they’ve eclipsed since his hiring.

Morrison was named the head coach at Texas A&M in late 2022.

“When I took this job, whenever I was telling people, they had eyebrows raised a little bit, questioning,” Morrison said.

“And it’s funny because, like, a year in, when all of the changes in college athletics started happening, and they also realized resources were really important, so then it was the first thing that happened. And the other thing that I knew was going to happen was just the conference was going to explode, and I knew it for a few reasons.”

Texas — a perennial power since former head coach Mick Haley broke a barrier (NCAA champs had hailed from California or Hawaii) by defeating Hawaii in the 1988 national championship — joined the SEC in 2024 with fellow newcomer Oklahoma.

But the most monumental shift was Skinner’s breaking through during the COVID-impacted 2020-21 NCAA national championship, during which an SEC team hoisted the trophy for the first time in history.

“I really respect what Craig did out in Kentucky,” Morrison said. “And I said at the time, I had a feeling of, I could do what I believed I could do with this program.”

Belief lies at the heart of the accomplishment of not only reaching the national championship as Texas A&M, or Kentucky, but also of an all-SEC title match. Belief is its root.

“Obviously, I knew that no SEC team had ever won a national championship,” Skinner said. “And in recruiting, it was, ‘Hey, we’re going to be the first team in the SEC to win a national championship. Come join us.’ And sometimes that’s a little … it’s not for everybody. Because to be really good, you’ve got to invest a lot of time.”

In the 20 years between Skinner’s national title as an assistant coach at Nebraska and Kentucky’s national championship, he maintained the commitment to the dream and has not once missed the postseason during his tenure as head boss.

“I’d been a part of a national championship program,” Skinner said. “And just wanted people to feel what that was like. And not just winning it, but the work, and the time and the competitive desire it takes to get to that point. Because that’s the way life is. And so for us to do that, I think, broke down doors that, either Kentucky could do it again, or someone else in the league can do it.”

Like Skinner, Morrison’s team hasn’t missed the NCAA Tournament since his hiring, with the Aggies earning a berth in 2023 after an eighth-place finish in the SEC, and reaching the Sweet 16 in 2024 after finishing fifth in the league.

Suddenly, each coach has led their respective programs to historic success in 2025, regardless of Sunday’s outcome. And their fan bases couldn’t be happier.

For Skinner and Morrison, there’s a certain power to being somewhere that could fall in love with the “special” moments, despite the fact that there may be other programs on campus that take up significant spotlight.

The Wildcats, whose men’s basketball team stands among the most successful in the history of the sport. The Aggies, whose football team will begin its college football playoff journey Saturday in a first-round playoff matchup with Miami (Fla.).

“Kentucky is a flagship institution of the state,” Skinner said. “And there’s no pro sports, and when you do something special, they will get all in, all the time. And we’re feeling that right now.”

Despite the fact that revenue sharing, NIL and the transfer portal have rocked the traditional essence of college sports, two of the college sports’ biggest brands can — as the conference likes to say — “mean more” than just men’s basketball or football.

Morrison said that he was intentional in taking a job at a school that demonstrated a serious investment in women’s athletics, and believes that there is truly room for everybody to succeed.

“There is a balance,” Morrison said. “And I think they do an amazing job of making sure that everyone can be excellent, and giving us the resources within our sports and doing their due diligence on what that’s going to take within each sport to make sure that we can be competitive.”

Morrison’s Aggies have not yet defeated Skinner’s Wildcats, and fell most recently at home, 3-1, in College Station on Oct. 8. Texas A&M, the two-seed in the league tournament, failed to reach the SEC championship match, where the Aggies would’ve had the opportunity to get its revenge.

The return of the SEC Tournament this season just so happened to coincide with the first-ever All-SEC national championship, but its high-powered talent and competitiveness on display earned viewership that would’ve been unthinkable when Skinner first took the Kentucky job, and is more than anything a testament to the elevated floor of Southeastern Conference volleyball.

“The SEC is known for putting on championships,” Skinner said. “And we’re the only sport in the league that didn’t have a championship. And so, there’s a lot of different minds and thoughts going into it, and culminating in what I thought was a spectacle for volleyball. And the league did a tremendous job of putting a spotlight on our athletes.”

In the 2025 SEC Tournament, the Wildcats drew national attention for pulling off a reverse sweep against the Texas Longhorns, who had defeated the Aggies, 3-1, in the semifinals.

Is there room for comparison in the experiences between the resurrected SEC Tournament, and a deep NCAA Tournament run? Outside of the physical and mental energy and effort, Skinner said, or the long haul of difficult competition in quick succession in hopes of a title, only time will tell.

“They had to play tough matches,” Skinner said. “We had to play tough matches. And the more you experience, the more types of matches and feelings you have, the more things you can pull from. So Sunday’s match is going to be completely different in terms of what we feel, but hopefully, at some point during this season, we have been there before, and we can draw from those situations.”

Sports

Kentucky volleyball game time, Texas A&M-UK NCAA Championship channel

Dec. 21, 2025, 5:08 a.m. ET

KANSAS CITY, MO — The NCAA Volleyball Championship match between the top-seeded Kentucky Wildcats and No. 3 Texas A&M is the first all-SEC final in the sport’s history.

UK coach Craig Skinner said after Thursday night’s national semifinal that the 2025 title card spoke to the league’s status as a “volleyball powerhouse.”

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that two SEC teams are playing for the national championship,” he said. “The coaches in our league have worked incredibly hard to put ourselves on the map.”

Here’s everything you need to know to keep up with the match from home:

No. 1 Kentucky vs. No. 3 Texas A&M will be broadcast live on ABC from the T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Missouri. The match is scheduled for 3:30 p.m. ET.

Buy Kentucky volleyball tickets here

Volleyball coaches like UK’s Craig Skinner want more linear TV spots for the NCAA Tournament, specifically the first two rounds, which were broadcast on ESPN+. While folks with the governing body and sports network acknowledge there’s room for improvement, they also warn programming an event with so many matches in a crowded December slate isn’t that simple. Read more here.

Brooklyn DeLeye joined Kentucky volleyball determined to rise to the top. Now, she’s back near her home state and on the brink of an NCAA championship. Read more here.

Read about how UK volleyball coach Craig Skinner’s people-first approach has vaulted the program to sustained national relevance here.

The Wildcats are known for their bench choreography. Read how UK’s sideline antics have helped lead it to the NCAA Volleyball Tournament national semifinal here.

Kentucky and Texas A&M volleyball did play this season. UK won 3-1 in College Station, Texas, on Oct. 8.

Today’s national championship is the first all-SEC volleyball final.

It will be the 28th all-time meeting between UK and Texas A&M. The Wildcats are 17-10 against the Aggies, having won the last four straight.

UK volleyball won the 2020 NCAA Tournament, which was played in April 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Wildcats have played in 27 NCAA Tournaments, including this one (1983, 1987-88, 1990, 1992-93, 2005-2025). Twenty-one of those appearances came under Skinner.

UK has made 15 NCAA Regional Semifinals and now two Final Fours. The program has one national championship from the 2020-21 season.

Wildcats will play the No. 3 Texas A&M Aggies in the NCAA Championship Sunday. Here’s a look at the tournament schedule:

- Championship: Dec. 21 at T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Missouri

Click here to view the complete bracket.

- Aug. 23: Kentucky 4, Ohio State 0 (exhibition)

- Aug. 30: Kentucky 3, Lipscomb 0

- Aug. 31: Nebraska 3, Kentucky 2

- Sept. 5: Kentucky 3, Penn State 0

- Sept. 6: Kentucky 3, New Hampshire 0

- Sept. 10: Pitt 3, Kentucky 0

- Sept. 13: Kentucky 3, SMU 1

- Sept. 14: Kentucky 3, Houston 0

- Sept. 18: Kentucky 3, Louisville 2

- Sept. 20: Kentucky 3, Washington 0

- Sept. 24: Kentucky 3, South Carolina 0

- Sept. 26: Kentucky 3, Georgia 0

- Oct. 3: Kentucky 3, Ole Miss 0

- Oct. 8: Kentucky 3, Texas A&M 1

- Oct. 12: Kentucky 3, LSU 0

- Oct, 15: Kentucky 3, Auburn 0

- Oct. 19: Kentucky 3, Florida 2

- Oct. 24: Kentucky 3, Mississippi State 1

- Oct. 26: Kentucky 3, Alabama 0

- Oct. 31: Kentucky 3, Vanderbilt 0

- Nov. 2: Kentucky 3, Texas 0

- Nov. 6: Kentucky 3, Missouri 1

- Nov. 9: Kentucky 3, Tennessee 1

- Nov. 14: Kentucky 3, Oklahoma 2

- Nov. 16: Kentucky 3, Arkansas 0

- Nov. 23: Kentucky 3, Auburn 0 (SEC Tournament Quarterfinals)

- Nov. 24: Kentucky 3, Tennessee 1 (SEC Tournament Semifinals)

- Nov. 25: Kentucky 3, Texas 2 (SEC Tournament Final)

- Dec. 4: Kentucky 3, Wofford 0 (NCAA Tournament First Round)

- Dec. 5: Kentucky 3, UCLA 1 (NCAA Tournament Second Round)

- Dec. 11: Kentucky 3, Cal Poly 0 (NCAA Tournament Regional Round)

- Dec. 13: Kentucky 3, Creighton 0 (NCAA Tournament Regional Final)

- Dec. 18: Kentucky 3, Wisconsin 2 (NCAA Tournament National Semifinal)

- Dec. 21: Kentucky vs. Texas A&M (NCAA Tournament Championship)

Click here to see who the Aggies have faced this season.

Kentucky’s 2025 and 2020-21 teams were both crowned SEC champions.

The 2020-21 team went 24-1, dropping one conference match to Florida (3-2) and never losing on its home court.

The 2025 team is 30-2, riding a 27-match win streak dating back to September and encompassing the whole SEC slate as well as every match at Historic Memorial Coliseum.

The Wildcats have won nine consecutive conference titles, which is a Power Four conference volleyball record.

Kentucky volleyball takes a 27-match win streak into the NCAA Championship match after a perfect run in SEC play and at Historic Memorial Coliseum this season.

Craig Skinner’s contract with Kentucky volleyball runs through June 30, 2029. His base salary is as follows:

- July 1, 2022-June 30, 2023: $450,000

- July 1, 2023-June 30, 2024: $475,000

- July 1, 2024-June 30, 2025: $525,000

- July 1, 2025-June 30, 2026: $525,000

- July 1, 2026-June 30, 2027: $525,000

- July 1, 2027-June 30, 2028: $525,000

- July 1, 2028-June 30, 2029: $525,000

Skinner also receives $5,000 per contract year (payable on July 31 and Jan. 31) for “media and endorsement” obligations.

His incentive-based bonuses are not cumulative and include:

- $50,000 for a Final Four berth;

- $75,000 for an NCAA Championship

Yes, UK is spending its 2025-26 revenue-sharing budget on the following sports: football, men’s basketball, women’s basketball, baseball, softball and volleyball. The athletics department declined to provide a sport-by-sport spending breakdown when asked by The Courier Journal earlier this year.

Other schools that confirmed to The Courier Journal that they’re spending revenue-sharing dollars on volleyball are:

- Louisville

- Nebraska

- Ohio State

- Minnesota

- Creighton

- BYU

- TCU

- Texas A&M

Hudson and DeLeye are Kentucky’s star outside hitters. DeLeye is a junior and was named the Lexington Regional’s Most Outstanding Player.

Hudson transferred to Kentucky from Purdue for her senior season. She was named to the Lexington Regional All-Tournament Team. Hudson was also awarded SEC Player of the Year and Newcomer of the Year.

Both players have been critical for UK’s success all season. They proved especially clutch during the Elite Eight match, combining for 32 of the team’s 47 kills.

- Trinity Ward (DS/Libero, Fr., 5-foot-7)

- Ava Sarafa (Setter, R-So., 6 foot)

- Jordyn Dailey (Middle Blocker/Right Side, R-So., 6-foot-2)

- Kassie O’Brien (Setter, Fr., 6-foot-1)

- Eva Hudson (Outside Hitter, Sr., 6-foot-1)

- Brooke Bultema (Middle Blocker, R-So., 6-foot-3)

- Georgia Watson (Outside Hitter, Fr., 6-foot-3)

- Kennedy Washington (Middle Blocker, So., 6 foot)

- Molly Berezowitz (DS/Libero, Jr., 5-foot-5)

- Molly Tuozzo (DS/Libero, Jr., 5-foot-7)

- Hannah Benjamin (Outside Hitter, R-Fr., 6-foot-1)

- Lizzie Carr (Middle Blocker/Right Side, R-Jr., 6-foot-6)

- Brooklyn DeLeye (Outside Hitter, Jr., 6-foot-2)

- Asia Thigpen (Outside Hitter, So., 5-foot-11)

Click here to see who plays for the Aggies.

Reach college sports enterprise reporter Payton Titus at ptitus@gannett.com and follow her on X @petitus25. Subscribe to her “Full-court Press” newsletter here for a behind-the-scenes look at how college sports’ biggest stories are impacting Louisville and Kentucky athletics.

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoSoundGear Named Entitlement Sponsor of Spears CARS Tour Southwest Opener

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoDonny Schatz finds new home for 2026, inks full-time deal with CJB Motorsports – InForum

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoMen’s and Women’s Track and Field Release 2026 Indoor Schedule with Opener Slated for December 6 at Home

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoBlack Bear Revises Recording Policies After Rulebook Language Surfaces via Lever

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoHow Donald Trump became FIFA’s ‘soccer president’ long before World Cup draw

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoDavid Blitzer, Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoJR Motorsports Confirms Death Of NASCAR Veteran Michael Annett At Age 39

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoRick Ware Racing switching to Chevrolet for 2026

-

Sports2 weeks ago

West Fargo volleyball coach Kelsey Titus resigns after four seasons – InForum

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoWomen’s track and field athletes win three events at Utica Holiday Classic