NIL

Arizona Top 4 in Power 4 College football 2025 Transfer portal experience added

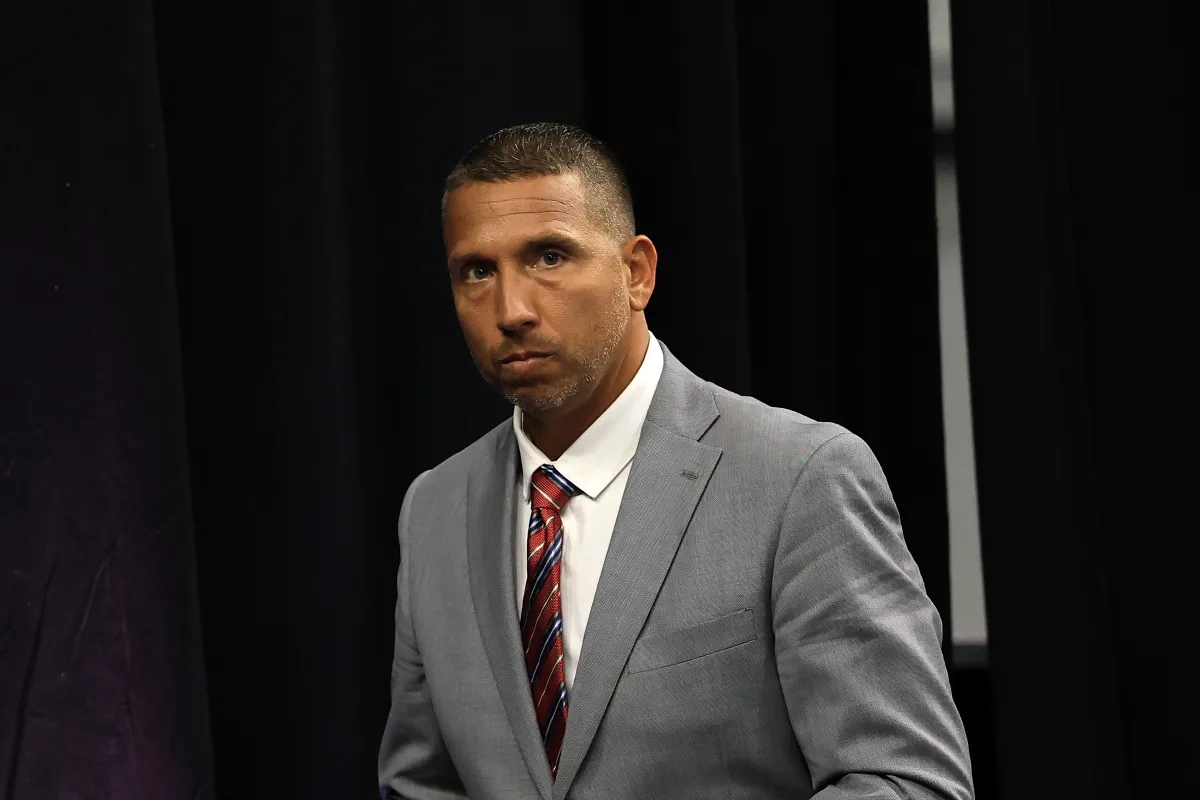

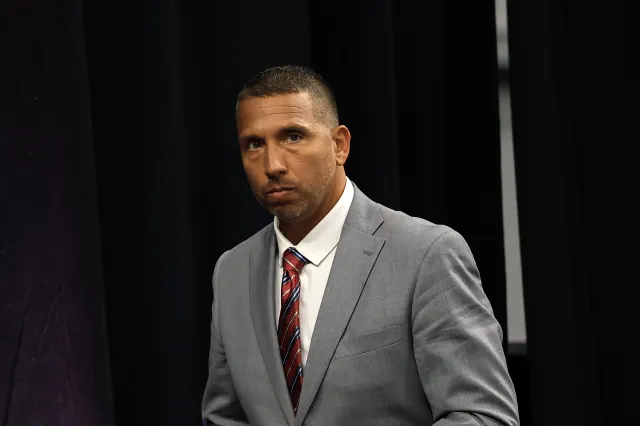

Arizona ranks fourth nationally with 26,465 snaps and is third with 403 among their 27 incoming transfers, as ESPN examined “College football 2025: Transfer portal experience added.” Brent Brennan and the Arizona staff are counting on transfers being significant contributors in 2025.

After losing 35 scholarship players to the Transfer Portal after the 2024 season, Brennan and the Arizona staff had to bring in the 27 transfers to add valuable experience and build depth on the 2025 roster. Retaining Noah Fifita for the second consecutive offseason was the most important detail on the 2025 Arizona roster.

Adding more talent to surround Fifita in 2025 was critical. The loss of All-American Tetairoa McMillan made wide receiver a priority for Arizona entering the 2025 season. Wide receivers Kris Hutson and Javin Whatley are the most experienced transfers Arizona added to the 2025 roster.

Hutson produced at a high level playing at Washington State and Oregon. Whatley is one of many Football Championship Subdivision transfers Arizona has added to the 2025 roster. Per Olson, Hutson is the third most experienced WR in the portal with 32 starts and 1,905 snaps in his career.

“4. Arizona Wildcats

Incoming transfers: 27

Starts added: 403

Snaps added: 25,467Experienced additions: WR Kris Hutson, Washington State (1,905 snaps); WR Javin Whatley, Chattanooga (1,623); DB Ayden Garnes, West Virginia (1,571); LB Blake Gotcher, Northwestern State (1,565); OL Ka’ena Decambra, Hawaii (1,506)

The experience level of the Wildcats’ portal haul really stands out, with a dozen players coming in who’ve played more than 1,000 D-I snaps.”

Max Olson, ESPN

Olson added that Texas State transfer running back Ismail Mahdi is fourth in FBS in the last two seasons with 3,593 all-purpose yards. Mahdi was first nationally in 2023 with 2,169 all-purpose yards and earned first-team All-American as an all-purpose player.

Olson closed out his summary of Arizona, stating, “If the Wildcats can solidify their offensive line with their six portal additions and find a few gems among their 10 FCS transfers, they could have the right ingredients for a nice bounce-back season.”

NIL

Matt Campbell’s Transfer Portal Budget at Penn State Revealed

New Penn State head coach Matt Campbell is getting something for the first time in his coaching career — a massive NIL budget to play with.

Campbell was a last resort for Penn State in its coaching search, though it happened to stumble upon a coach who consistently did more with less at Iowa State, who faced recruiting challenges and could not match the resources of a larger-profile school.

More news: Penn State, Matt Campbell Given Update on Rocco Becht Transfer

Now, Campbell gets a chance to compete with the big boys for blue-chip players out of high school and in the transfer portal, and his first test will come on January 2, when he can nab a hodgepodge of talent.

Penn State is a true powerhouse in the sport, an established top school with high ambitions, a big national spotlight, and, according to the latest reports, the ability to pay players competitively.

Per college football insider Matt Fortuna, Campbell will be getting “roughly $30 million in NIL money,” a figure also mentioned in a story from The Athletic.

More news: Lane Kiffin Gets Brutally Honest On Ole Miss Against Georgia in Sugar Bowl

While he will have the resources, Campbell stressed during his introductory press conference that the amount of money is not as significant as how it is spent.

“The financial aspect, I think, is certainly unique,” Campbell said. “One of the great things that we have here is the sacrifice that [Athletic Director] Pat [Kraft] and his team have made to be competitive at the highest level to give yourself a chance to build the best team.

“Now, I think sometimes in college football we can get lost on the financial piece of it. Do I think it’s important? Absolutely. But I think the reality is that it cannot be priority No. 1.

“It’s great to have the money, but it’s using the money wisely. It’s using the resources correctly, building the right team and knowing what you’re trying to spend those things on and making sure it’s about the right things.”

At the turn of the year, Campbell will get to show the ability to use money wisely on a large scale, and if he does, Penn State could quickly become a National Championship contender once again.

More news: Indiana Predicted to Land Top Transfer QB as Fernando Mendoza Replacement

For more college football news, head to Newsweek Sports.

NIL

Can Texas Tech billionaire booster Cody Campbell fix college sports?

LEAN IN CLOSELY. Cody Campbell is surprisingly soft-spoken. On a cool Friday night in Fort Worth, Texas, a night built for high school football, over the din of cowbells and rattling bleachers and Will Smith’s “Wild Wild West,” it’s difficult to hear the man who has become the loudest, most controversial voice in a fight to shape the future of college sports.

Did he just say he hates political campaigning? The guy who paid millions of dollars in the past half decade to capture the ear of President Donald Trump? The guy who has paid millions more to put himself in television ads and grab headlines with brash statements about the greed and ego of college football’s power brokers? Is that what he just said? It is.

Campbell is calmly fiddling with the lid of a paper coffee cup, watching the All Saints’ Episcopal High School football team blow out its final home opponent of the season. He doesn’t holler at coaches or referees. His only reaction when his 14-year-old son, a 290-pound mauler on the offensive line, flattens an opposing linebacker is a pair of raised eyebrows and a small grin that barely creases the edges of his salt-and-pepper goatee.

Campbell, 44, is an oil-made billionaire. At Texas Tech, where he has bankrolled much of the football team’s unprecedented launch into national relevance and current spot in the College Football Playoff, he gets as many interview requests as the head coach. The former offensive lineman had a brief NFL career before co-founding one of the largest private oil and gas companies in West Texas, a business he still runs on top of his duties as a father of four, an active Republican fundraiser and the chairman of Texas Tech’s board of regents.

“It feels like every day is 10 days,” Campbell says, taking a swig of his coffee.

He’s busy. So why, now that he has helped repair the Red Raiders football program, is Campbell spending significant time and money trying to fix college sports? That’s the question most people in the industry ask when they first meet him. What does he really want?

Most of those folks, Campbell said, leave their meetings surprised. He is not the backslapping, overly confident charmer in a ten-gallon hat that headlines might lead you to imagine. He doesn’t stand out in the crowd of parents filling the bleachers despite his broad shoulders and 6-foot-4 frame.

“I’m not what they expect me to be, I guess,” he says. “I’m not J.R. Ewing or whatever.”

Campbell and his adversaries — most notably the commissioners of the four power conferences — agree that the NCAA is suffering from an inability to enforce its own rules. They agree that a fix will require help from Congress. But each side accuses the other of proposing solutions that are motivated by self-interest rather than what’s best for college sports.

Is Campbell a misinformed newcomer, as some commissioners have asserted, who bought his way into influence? Or is he the fresh voice that a broken system needs to embrace its new professionalized reality?

“I’m a threat to the status quo,” Campbell says. “But the status quo is failing. … A lot of people want to hold on to the way things used to be. The fact is, we’ve already crossed the Rubicon.”

ON THE MORNING of Texas Tech’s top-10 showdown with BYU in early November — the biggest game in Lubbock in nearly 20 years — Campbell carves through campus, leaving a wake of fans spinning their necks and calling after him.

Bundled-up frat boys pause mid-beer-sip and smack their buddies in the ribs.

“Yo, that’s the rich dude! Sir, thank you!”

“Bring ‘er home, Cody! Bring ‘er home!” they yell through cupped hands.

A man in a Tech jersey asks for a selfie. He’s holding a poster of Campbell’s face. The eyes have been replaced by laser beams and it reads “Mad Cuz You Broke.” Campbell chuckles, then obliges.

Campbell is the chief architect of an NIL collective, The Matador Club, that has paid more than $60 million to athletes at Texas Tech since 2022, much of it to the football team. The club’s aggressive approach to the NCAA’s new rules has rebuilt a program that historically struggled to make bowl games into a legitimate contender to bring a national championship to the football-crazed outpost in West Texas.

Campbell served on the committee that hired coach Joey McGuire in 2021. He donated $25 million to help rebuild the football stadium. He spearheaded the fundraising effort for the parts of the football payroll that didn’t come directly out of his pocket. He even watched film to evaluate prospects for one of the nation’s best transfer portal classes this offseason.

For his efforts, Campbell moves through a Texas Tech game day with the same unfettered reign as Jerry Jones at a Cowboys game. He might as well own the place. Outside the stadium, he chats with a security guard and slides into a VIP section behind the set of ESPN’s “College Gameday,” barely breaking stride.

The show’s stars take time between their segments to shake his hand. Big 12 commissioner Brett Yormark introduces Campbell to a pair of television executives in sharply tailored suits. Campbell, in dad jeans and a black baseball cap, nods along as they speak into his ear. They’d like to set a meeting. They’ll come to him.

The university’s president strolls over to say hello. He knows Campbell’s wife, Tara, and each of their kids by name. Kent Hance, a former chancellor and legendary yarn-spinning Texas political powerbroker who is the only man to beat George W. Bush in an election, seeks him out with a familiar smile and wave.

“It doesn’t really feel strange,” says Tara, also a Tech alum, as another fan asks her husband for a photo. “These are our people. It feels like family.”

Campbell’s roots run deep here. His maternal great-grandfather, Boyd Vick, was a member of the university’s first class in 1925. The Vicks, according to family lore, arrived in West Texas in a covered wagon in the early 1900s in search of work during a silver rush. When Boyd matriculated to the new university, he played on the football team, naturally. More than a dozen of his descendants now hold Texas Tech degrees.

Texas Tech recruited Cliff Campbell, Cody’s father, to play for the football team in the early 1970s. Cliff’s father worked in the oil fields when he returned home from fighting at Iwo Jima. Cliff’s mother picked cotton to help make ends meet. Cliff was the first member of his family to attend college, thanks to football.

Cody Campbell, having passed up an offer to go to Harvard to keep the family tradition alive, now rides to campus from his home in Fort Worth on an Embraer E550 with a slick, polished wood interior outfitted with throw blankets that have his company logo embroidered in the corners. Covered wagons to private jets in the space of a century, an American success story fueled by the opportunities provided by college sports.

“It’s generational for me,” Campbell says.

He wasn’t always beloved in Lubbock.

In early 2021, Campbell was worried about his alma mater and its place in the future of college sports. Months before college athletes started making money, months before Texas and Oklahoma announced plans to ditch the Big 12 for the SEC, stoking fears that the biggest brands in college football might eventually split the sport and leave programs in small markets like Lubbock in their dust, Campbell was angling for a seat on Texas Tech’s board of regents.

He wasn’t happy with the direction of the football program. And he wasn’t shy about it. On fan message boards and social media, he railed against then-head coach Matt Wells. Campbell was loud and disruptive. Several members of the university’s board didn’t want Gov. Greg Abbott to appoint him.

“He was more outside the tent, throwing rocks for a period of time,” says Dusty Womble, a fellow board member who was the lead donor for Texas Tech’s newly renovated, $242 million football facility.

Campbell sought help from Hance, a former congressman who still holds significant sway in Texas politics. Hance liked him, and surmised Campbell was only a rabble-rouser because he wasn’t yet in a position to act. Hance borrowed a phrase from the ultimate Texas powerbroker, Lyndon B. Johnson, to explain why he nudged Abbott to put Campbell on the university’s board.

“I’d rather have him inside the tent and pissin’ out,” Hance says, “than outside the tent pissin’ in.”

Minutes before kickoff against BYU, Campbell and his son stroll past the big block letters that spell out Cody Campbell Field near the 20-yard line. Fans behind the end zone applaud as Campbell walks by. He smiles and looks down at his Texas Tech-branded sneakers, school pride from head to toe.

“He came on to the board, and I think that required him to maybe be a little more politically correct and not as disruptive,” says Womble, who happily works shoulder-to-shoulder with Campbell as vice-chair of the board. “He became part of the system, part of the solution.”

Campbell heads up the stadium tunnel toward the locker room, past the marching band. A voice from the brass section shouts, “Thanks for buying us an O-line!”

That one gets him to laugh as he reaches for the door to the locker room. He greets players and grabs a bottle of water from the team’s cooler. McGuire stops by and shakes his hand. “This guy’s a stud. He’s a stud,” the coach says before turning and calling his team up to join him by taking a knee.

Campbell puts his arm around his son during the team prayer and McGuire’s pregame speech. Then, Campbell follows the team through the stadium tunnel. The players turn right to take the field. Campbell and his son turn left to head to their suite, where the rest of their family, friends and Patrick Mahomes — perhaps the only Texas Tech alum drawing a bigger buzz on campus — are waiting for them.

Hance sits in his own suite down the hallway with his family and watches Texas Tech physically dominate BYU en route to a 29-7 win, the full manifestation of a program Campbell has helped to overhaul. The stadium remains full well into the fourth quarter. For a growing university trying to compete for applicants with campuses in the state’s biggest cities, you can’t buy marketing this good. Well, except they did.

“I knew he’d figure out how to be an insider once he was on the inside,” Hance says.

His daughter-in-law leans over to ask whom Hance is talking about.

“Oh, Cody Campbell. I haven’t met him yet,” she says. “When you see him, tell him thank you for me.”

LEAN BACK NOW. Cody Campbell is in your living room. He’s staring right through the television to warn you that college sports are at risk. He’s standing alone in Texas Tech’s empty stadium with a football in his hands, identified only as a former player.

He’s looking at you, but he’s talking to Congress. Athletic departments are bleeding money, he says. Women’s sports and Olympic dreams are in “immediate danger” of vanishing. He has the answer. A “single change” that can generate enough money to “protect all sports at all schools.” He implores Congress to act.

If it were an election year, you might think he was running for office. The television ads, which ran frequently during college football games early this fall, were part of a strategic plan for Campbell to more substantially elbow his way into an ongoing debate among federal lawmakers.

“Let’s save college sports,” he says, “before the clock runs out.”

Campbell believes college sports need more money and a more effective organization to regulate how that money is spent. He is lobbying Congress to amend the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 to allow college sports to negotiate TV contracts as a single group, as professional leagues such as the NFL and NBA do. Colleges currently negotiate their TV contracts by conference, which gives media executives more bargaining power and favors the Big Ten and SEC, which both have higher ratings and bigger budgets.

Campbell says he has commissioned research that shows if colleges could band together, their TV rights would be worth roughly $7 billion — almost double what they make in total now. It’s a change that would direct a larger share of revenue to schools like Texas Tech, making the Red Raiders less dependent on billionaire alums to help them compete.

The current leaders of college sports view Campbell’s proposal as a naive solution to a complex, tangled problem. SEC commissioner Greg Sankey told the Associated Press in October that Campbell has a “fundamental misunderstanding of the realities of college athletics.” It could be 10 years or more before current deals expire and open the door for a big group contract. And that’s assuming all conferences would want to join forces. Commissioners and other media industry experts also say Campbell’s $7 billion projections are optimistic, perhaps wildly so.

Sankey, along with Yormark, the ACC’s Jim Phillips and the Big Ten’s Tony Petitti, declined to be interviewed for this story.

In his interview with the AP, Sankey said he had “serious concerns” about the accuracy of many of Campbell’s statements. In podcasts and other appearances, Campbell has frequently shared statistics that many believe exaggerate the NCAA’s current crisis. He often says that FBS athletic departments lost an average of $20 million per school last year. When asked how he arrived at such a daunting number, Campbell acknowledged his math doesn’t include the money athletic departments receive from student fees and other support many universities provide to their athletic departments in exchange for the marketing value and campus community that sports help to build.

Campbell also frequently says that more than 180 teams have been cut since the NCAA announced plans to allow schools to pay their athletes. A website he launched earlier this year makes the same claim, citing as its source a college wrestling blog that started tracking program cuts during the pandemic. The list includes many teams at junior colleges and NAIA schools that are not impacted by NCAA rule changes. Of the 180-plus teams on that list, only three are from FBS conferences. Isn’t that a little misleading?

“Probably,” Campbell says with a shrug.

Nonetheless, he says the threat of more cuts remains real, especially if Congress adopts the NCAA’s ideas instead of his. The NCAA and its schools have lobbied for an antitrust exemption that would allow them to place limits on how athletes are paid, but it doesn’t cap other spending races in college sports or provide routes to create new revenue.

Campbell argues that without a significant overhaul — one that spreads money at least a little more evenly among FBS schools — an antitrust exemption would exacerbate the financial gap between the NCAA’s richest few dozen programs and everyone else, forcing many schools to hollow out the sports that don’t drive large profits or spend beyond their means in an attempt to keep up.

When it comes to keeping as many schools as possible under the same banner, and sharing from the same pot of revenue, Campbell has found at least one sympathetic ear. NCAA president Charlie Baker said Campbell’s ideas for changing the Sports Broadcasting Act are a dangerous “Pandora’s box,” but he agrees with some of Campbell’s other suggestions about making sure money generated by power conferences can continue to help fund smaller schools.

“When he talks about that, he’s kind of singing my song,” Baker told ESPN. “… One thing I appreciate about Cody is he’s got opinions and he’s willing to share them. He’s willing to put them out there. That’s not a bad thing.”

IN THE DAYS after the 2024 presidential election, Campbell paid a visit to his longtime friend Brooke Rollins at an office she rents in Fort Worth to discuss a new way to share his ideas about college sports.

Rollins would soon be named Secretary of Agriculture for Trump’s second term. She had spent the past three years as president and CEO of the America First Policy Institute, a conservative think tank she cofounded thanks in large part to a seven-figure check from Campbell. He has donated millions more to a variety of conservative political causes for the past decade. AFPI, though, put him on the ground floor of an organization so tightly connected to Trump’s administration that it was dubbed the “White House in Waiting” in between the president’s two stays in office.

Campbell had to decide how he wanted to wield the influence his loyalty had delivered. He says the president’s transition team floated the idea of making Campbell an ambassador. He speaks some Spanish and could fit well in Latin America. Campbell wasn’t interested in moving his wife and four young children to Buenos Aires or San Salvador. Nor was he interested in stepping away from the thriving oil and gas business he built with his lifelong best friend. Campbell had another idea.

“How about college sports?” he asked.

Rollins smiled, unsurprised. A season-ticket holder at her alma mater, Texas A&M, she understood the importance of college sports and the current turmoil of the industry. She knew Trump had a strong interest in sports. She promised to make some introductions.

Two months later, Campbell arrived at the White House with a set of thick binders, each filled with more than 700 pages of data, reports and suggestions. Campbell, who was formally appointed to the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness and Nutrition this July, has visited Washington, D.C., at least once a month since Trump took office. Campbell has been “tremendously persistent” in his effort to keep college sports on the administration’s agenda, according to a source familiar with his work at the White House. The source says Campbell has carved out a unique spot among the president’s advisers. On issues such as tariffs or foreign relations, Trump’s administration will listen to several people. On college sports, they listen to Campbell “unlike anybody else on any other issue,” the source says.

“If he’s going to sit down and talk to you about something, he’s going to be more prepared than you are. I can assure you,” says John Sellers, Campbell’s business partner. “That’s kind of been him forever.”

Sellers moved to the small town of Canyon, Texas, 100 miles north of Lubbock, in the summer before seventh grade. When he arrived for the football team’s opening two-a-day practices, Campbell was one of the first new classmates he met. Sellers played right guard. Campbell played right tackle. The following year, they switched — “I got a little taller, he got a little fatter,” Sellers says — and that’s where they stayed for the next four years on the offensive line of the Canyon High Eagles.

Campbell and Sellers were roommates and teammates at Texas Tech when they launched their first business, buying a plot of land on the edge of Lubbock and prepping it to sell to a real estate developer. They have been partners more or less ever since, interrupted only briefly by Campbell’s 15-month NFL career with the Indianapolis Colts.

When real estate went belly up in 2008, the buddies from Canyon tried the oil and gas industry. They scoured small courthouses in Louisiana and South Texas to determine who owned the mineral rights they wanted to purchase and spent long days working to build trust with local landowners. Since then, they’ve sold four iterations of their Double Eagle Energy (a nod to their high school mascot) for a total of roughly $13 billion.

Sellers says he operates by gut feeling. Campbell is the analytical partner — an NFL player whose all-state honors in high school were for his work on the Canyon High debate team. Campbell says he has been an avid researcher since his grandmother bought him his first shares of a sports trading card company when he was in grade school and taught him how to track the market in newspaper clippings.

“He’s the ‘ready, aim, fire’ guy,” Sellers says. “I’m more of a ‘ready, fire, aim’ kind of guy.”

Campbell and Sellers credit their legendary coach Mike Leach with instilling in them an ability to tirelessly sweat small details. Campbell says he wants his children, and thousands of other kids, to have the same opportunity to learn life lessons from their coaches in college sports.

The rest of their success, Campbell says, comes from the values they absorbed growing up in Canyon.

“People out there are just tough,” he says. “They understand that there are good years and bad years. It’s a boom-and-bust area. … You have a bunch of people who aren’t afraid to take risks, who aren’t afraid to break their back to make a living.”

Campbell took risks and built a fortune. Now his résumé — the shrewd oil billionaire with very powerful friends — walks into a room before he does. He says he’s still adjusting to his new reality, still reconciling the gap between public perception and his own view of his story.

“I see myself as a kid from a small town in West Texas,” he says. “That’s who I am.”

THE KID FROM CANYON looks comfortable dressed in a custom-tailored suit and crisply pressed white dress shirt during the first week in December as he steps off the escalator in the lobby of a Las Vegas casino convention center.

Campbell is here to speak to a room of college sports insiders at the annual Intercollegiate Athletics Forum hosted by Sports Business Journal. Campbell and his interviewer, SBJ publisher Abe Madkour, take their seats on stage. The cavernous ballroom suddenly finds a bit of a pulse. Lawyers and administrators tuck away their phones and trade glances with colleagues, perhaps hoping for some fireworks at the end of two days of repetitive panel discussions.

Campbell unspools some of his usual arguments from what has become a stump speech in recent months, sharing his backstory and his plans for adding billions of dollars to the system. He loses his rhythm only temporarily when Madkour mentions that some conference commissioners actually like him. Campbell pauses, bobs his head. “Well … some of them,” he says. The room laughs with him.

Four days earlier, Campbell was at AT&T Stadium watching Texas Tech win its first Big 12 championship. A day before that, he was in Waco, watching his son’s team win a state title. Whatever hangover he was nursing — “I had not had Fireball shots in quite a while,” Campbell says — was wiped away by a warmer-than-expected reception at the conference.

Not that he doesn’t think he’s worthy of being an insider. Campbell points to his bona fides — four years on a university board, four years writing NIL contracts with players, experience dealing with private equity funders (a popular area of exploration among college sports leaders) and his own time as a student-athlete — as he scoffs at the people who say he doesn’t have the experience necessary to understand their industry.

“Everything has changed in the last four years, and I’ve been directly involved on an extremely detailed level for those four years,” he says. “I’m not sure that experience gained 30 years ago in college sports is necessarily that relevant today. … To say that I’m not qualified to be involved in it is sort of an absurd thing to say.”

On stage, Campbell’s interviewer begins to wrap up their 20-minute session with the question that persists in convention center hallways, echoed over cups of coffee in the morning and steak dinners at night: What’s in it for him?

Campbell told ESPN he has no financial stake in any proposed future college sports league. He isn’t interested in using this campaign as a platform to run for office. He doesn’t want to be the commissioner of a new national college football organization if one emerges. His only motivation, he says, is maintaining the same opportunities that launched his success for future generations.

“I know a lot of people have a hard time believing my intentions are pure,” he tells the ballroom in Las Vegas. “… We need to preserve this national treasure that we have. It belongs to all of us. We need to make sure we protect and preserve it, and we make it sustainable for the long term.”

Madkour tells the room that his publication was criticized by some attendees for putting Campbell on the agenda — offering him equal footing as Charlie Baker and conference commissioners.

“We thought he was an important voice to be heard,” Madkour says.

Campbell steps down from the stage and wades through a line of people who wait to shake his hand or pass him a business card. The conference commissioners — all of whom except Petitti were in town for the conference — didn’t stick around to listen to him speak. They didn’t really have to. Believe him or not, Cody Campbell is inside the tent now. His voice is unavoidable.

ESPN researcher John Mastroberardino contributed to this story.

NIL

How Texas Tech football assembled a Big 12 champion, CFP team

Dec. 29, 2025, 4:07 a.m. CT

Take a breath, because we’re almost to the Orange Bowl.

A lot has happened in the last 13 months or so for the Texas Tech football team. The Red Raiders got new coordinators on offense and defense, completely changed the program’s perception through its use of the transfer portal and NIL war chest, sat through eight-plus months of hyperbole and lip service, and, finally, made it all worthwhile with the Big 12 Championship and a spot in the College Football Playoff.

NIL

Dabo Swinney addresses next steps for Clemson football program after disappointing 2025

Dabo Swinney might have a long look in the mirror as Clemson hits the offseason. The Tigers lost 22-10 to Penn State in the Pinstripe Bowl to finish the year 7-6.

It was a year where, ironically both PSU and Clemson, were popular preseason national champion picks. Heck, some even predicted these two would square off for college football’s crown.

Swinney chalked these struggles up to big picture issues. If those can get rectified ahead of 2026 remains to be seen.

“It’s really more about just big picture of our issues from the season,” Swinney said postgame. “I know what’s real. I know what’s not. I don’t read what everybody else writes. I know what’s real. I have a good perspective when it comes to things that are in our control and what we’ve got to do better. We’ve got great people. I love all the people on my staff.

“But you evaluate everything. That’s just a part of our business, and it’s a part of the end of a season is you step back and — I don’t make emotional decisions, but first and foremost, it starts with what happened and how do we — is it personnel, is it scheme, is it bad calls, whatever. There’s a lot of things you evaluate as a coach.”

With the talent Clemson had back, such as QB Cade Klubnik and defensive linemen Peter Woods and T.J. Parker, there seemed to be a lot of NFL talent. But it just didn’t click as the Tigers found themselves 1-3 after four games, pretty much out of the CFP picture before even getting started.

Dabo Swinney promises to get it right for 2026

“Again, I know we’ve got seven wins, but we’re a lot closer than people think,” Swinney said. “That’s one of them things, boy, if you say that you get torn up on social media, people rip you I’m sure. But that’s the reality. I know what it is, and I know how close we are. It’s one more catch. It’s one more good throw. It’s a better call. It’s one stop. Next thing you know, you win a couple of those games that we lost early, and now you’ve got confidence and momentum and all those things matter. We just never got that.”

Swinney is 187-53 since 2008 with Clemson, winning nine ACC titles and two national championships. Heck, despite being 10-4 last year, the Tigers won the ACC and made it to the first round of the College Football Playoff.

To get back to that and beyond might take a philosophy or roster overhaul. But Swinney claims he knows what to do to get it right.

“It certainly affected us,” Swinney said. “But again, evaluate everything, make good decisions based on what my perspective is, and I’ll change what I need to change, stay the course on what I believe I need to stay the course on.

“Again, it’s never as good as you think, it’s never as bad as you think. I’ve done this a long time, and this is the second worst season we’ve had in 17 years. There will be something good come from it just like the last one we had in 2010. We had a lot of great things come from it. We’ll have a lot of great come from this one, as well.”

NIL

Kyle Whittingham admits he didn’t know if he was done coaching after stepping down at Utah before Michigan hire

On Dec. 12, Kyle Whittingham announced he’d be stepping down from his position as head coach at Utah after spending 21 seasons at the helm of the program. At the same time, Michigan fired head coach Sherrone Moore after he was charged with felony third-degree home invasion and two misdemeanors.

Just two weeks later, Michigan hired Whittingham to be its next head coach. During his introductory press conference on Sunday, the 66-year-old HC admitted he wasn’t sure whether he’d ever coach again after he resigned from Utah.

“It’s an honor to be able to be in this position. Twenty-one years at Utah. Stepped down a couple weeks ago. Wasn’t sure if I was finished or not. I still have a lot left in the tank,” Whittingham said. “You can count on one hand, the amount of schools that if they called, I would listen and I would be receptive to what they had to say.

“Michigan was one of those schools, definitely a top five job in the country, without a doubt. So, when the ball started rolling, and the more I learned about Michigan, the more excited I got. And I’m just elated to be here.”

Whittingham signed a five-year contract with Michigan worth an average of $8.2 million per year. Whittingham’s contract is 75% guaranteed. His 2026 salary is expected to be $8 million.

While Whittingham is far older than many of the other coaches who were signed during this hiring cycle, he’s also far more experienced. Whittingham was the head coach at Utah from 2005-25.

During his impressive tenure, he guided the Utes to a 177-88 overall record and three conference championships. Despite his illustrious résumé, Kyle Whittingham said he didn’t expect to hear from Michigan about its job opening.

“I didn’t expect that. Ironically enough, the timing was almost exactly the same from when I stepped down and when this job became open,” Whittingham said. “It was within a day or so of each other. Like I said when I stepped down, I felt like one thing I didn’t want to be is that coach that just stayed too long at one place.

“I just felt that the time was right to exit Utah. But, like I said, I still got a lot of energy, and felt like, ‘Hey, if the right opportunity came, then I would be all in on that.’ So, that’s what Michigan afforded me.”

NIL

‘Cinderella exists in college basketball’ but not college football

Everyone loves an underdog. That is, except everyone involved with college football.

As soon as two Group of Five schools qualified for the 2025 College Football Playoff, every college football talking head started falling all over themselves to explain why they didn’t deserve to be there, didn’t belong, and shouldn’t be allowed to compete there in the future.

The TV ratings for the first round of the CFP seemed to give pundits further ammunition, especially since most of their arguments had more to do with driving TV audiences than rewarding winners.

The war against college football Cinderellas has been intense, and you can add a somewhat surprising voice to the mix: NBC Sports college basketball announcer John Fanta.

As part of a wide-ranging interview with the New York Post’s Steve Serby, Fanta shared that while he enjoys seeing Cinderella teams compete in college basketball’s March Madness, it doesn’t work the same for college football.

“I would not have two Group of 5 teams in the Playoff,” said Fanta. “I am all for Cinderella. But Cinderella exists in college basketball.

“The opening weekend of the College Football Playoff was a dud. It’s not about picking Miami over Notre Dame. Miami beat Notre Dame. What doesn’t make any sense is the committee for weeks had Miami below Notre Dame, and then put Miami in over Notre Dame. So the committee has no rhyme or reason to what they are doing. That’s my issue with the Playoff. I think the Playoff is gonna deliver great games.”

Fanta’s argument is somewhat moot, as future editions of the CFP are highly unlikely to unfold as this year’s did, thanks in large part to Notre Dame’s revised MOU and likely changes to the ACC’s selection criteria.

Also, while the Tulane and JMU games were largely uncompetitive, plenty of Power 4 schools (and Notre Dame) have laid far worse eggs in CFP games.

If there’s a villain in this year’s CFP draw, it’s the Power 4 programs that didn’t do enough to justify their inclusion, rather than the G5 schools that earned the right under the current criteria.

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoSoundGear Named Entitlement Sponsor of Spears CARS Tour Southwest Opener

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoDeSantis Talks College Football, Calls for Reforms to NIL and Transfer Portal · The Floridian

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks ago#11 Volleyball Practices, Then Meets Media Prior to #2 Kentucky Match

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoSunoco to sponsor No. 8 Ganassi Honda IndyCar in multi-year deal

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoNascar legal saga ends as 23XI, Front Row secure settlement

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoAccelerating Inclusion: Breaking Barriers in Motorsport

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoNorth Florida Motorsports Park led by Indy 500 Champion and motorsports legend Bobby Rahal Nassau County, FL

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoEd Orgeron: Paying players via NIL would only require a ‘minor adjustment’

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

NASCAR, 23XI Racing, Front Row Motorsports announce settlement of US monopoly suit | MLex

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoWNBA’s Caitlin Clark, Angel Reese and Paige Bueckers in NC, making debut for national team at USA camp at Duke