College Sports

Baltimore Fishbowl | Still chasing the puck: Steve Wirth’s unbreakable bond with hockey

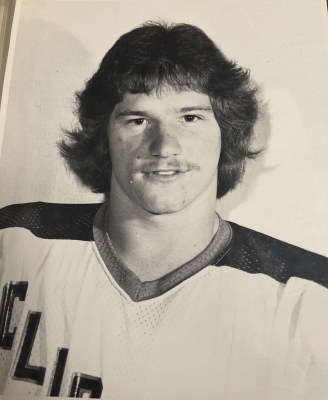

When Steve Wirth first attended a Baltimore Clippers ice hockey game with his brother, Tom, in 1962, he was 15 years old — and instantly hooked for life. Now 71 years old, the Baltimore native runs a hockey league with participants ranging from college students to retired professional players. But Wirth’s hockey journey was anything […]

When Steve Wirth first attended a Baltimore Clippers ice hockey game with his brother, Tom, in 1962, he was 15 years old — and instantly hooked for life.

Now 71 years old, the Baltimore native runs a hockey league with participants ranging from college students to retired professional players. But Wirth’s hockey journey was anything but typical.

Growing up near Patterson Park, Wirth first fell for soccer, then football, starring in youth leagues before stumbling into a local roller hockey league that changed everything.

“There was a lady who lived up the street from me who was a hockey buff, and I would go with her to Clippers games,” Wirth said. “And she said, ‘Once you get hockey in your blood, you can’t get it out.’”

A long and winding road

When an ice rink opened at Patterson Park, the 15-year-old Wirth skated every single day.

A year later, he joined a league at the Orchard Ice Rink in Towson. Then, he moved up to play for the National Brewers — an amateur senior team in the Chesapeake Hockey League (CHL) — competing against men twice his age.

“I’ve played other sports and as a kid, I was nervous when you go out on a baseball field or when you go out on a football field,” Wirth said. “When I first started playing ice hockey, I didn’t have a care in the world. All I thought about was playing hockey. So it’s something that fell into me.”

While playing in the CHL, Wirth caught the eye of Clippers General Manager Terry Reardon — whose son, Mike, also played in the league.

Reardon was impressed by Wirth holding his own against a higher level of competition, so he landed him a tryout with the Milwaukee Admirals of the then-called International Hockey League (IHL).

Wirth spent a month with the Admirals before IHL teams transitioned to the American Hockey League (AHL) due to financial struggles.

Back in Baltimore, he played with the semi-pro Washington Chiefs, facing college and senior teams along the East Coast.

Still chasing the big leagues, Wirth asked Reardon for a Clippers tryout. Reardon told him he wasn’t ready, but Wirth persisted — and eventually got his shot.

“Kids from Baltimore aren’t kids from Canada,” Wirth said. “It really didn’t hit me when I was speaking to him. I was way down the totem pole on my way up. It’s very rare that somebody from that level is going to be able to play in the American League.”

After training camp, Wirth signed a 25-game amateur tryout deal, just as the National Hockey League (NHL) was forming a union.

When a player who was cut from the Clippers suggested that Wirth ask for a trade to the Greensboro Monarchs — who needed defensemen — Wirth insisted that he stay with his hometown team.

“Of course, me being young and stupid and not, I should have listened, but I didn’t,” Wirth said. “I believe anybody who plays sports wants to play for their hometown team. I didn’t realize Terry Reardon knew every league there was because he had been through them all.”

On opening night, Reardon decided for him. During intermission, Wirth was called to the office and told he’d been traded to Greensboro. But his time as a Monarch was short-lived.

Wirth only spent two weeks in Greensboro before he was shipped to the El Paso Raiders. The Raiders provided a free room, free meals, and paid him $144 every two weeks — a stark improvement from his previous stop.

“Greensboro was havoc,” Wirth said. “It was the coach saying, ‘Come on guys, it’s time to practice.’ I was gung-ho about learning and playing. I didn’t really respect that coach for the way he was coaching. He just didn’t seem like he could push the guys. And that’s what I wanted to do.”

Wirth never allowed difficult circumstances to shake his resolve.

As the only American on the Clippers and Raiders, with most of his teammates hailing from Western Canada, he kept grinding.

In late 1975, with the Clippers piling up injuries, Reardon brought Wirth back and signed him to an official contract for $100 per game. But his fortunes would soon change again.

The Clippers folded after that season due to financial issues. They returned the following year in the Southern League, where Wirth tried out again but was the final cut.

Head coach Larry Wilson let Wirth practice with the team, and by December, he earned another official contract. He finished the season with the Clippers, but the league folded that February and was absorbed by the AHL.

Wirth’s AHL coach with the Clippers was Kent Douglas, a former NHL Rookie of the Year in 1962 as a 27-year-old and Stanley Cup winner. At 39 years old, Douglas was still playing while co-coaching and developed a close bond with Wirth.

Douglas helped Wirth land a spot with the last team he played for, the Toledo Gold Diggers — led by Ted Garvin.

After about three weeks, Wirth faced a potential trade to Dayton, Ohio but chose to return home to play for the Baltimore Blazers seniors team.

Though his official playing days were over, Wirth’s passion for hockey never faded. It remained a constant in his life — shaping the decades that followed.

Still laced up

After his playing career, Wirth’s father — a longtime Rod Mill steel mill worker — set him up with a job in the Armco steel mill.

Wirth had already seen the grueling conditions of his distant future during an open house at the mill in the early ‘70s and swore he’d never do it.

“So it took a four-inch square, and they would run it down to quarter-inch wire,” Wirth said. “And before they put what was called a manipulator in there, the guys had to catch the wire coming out, turn around, and put it in the other side of the mill. So my first thought of that was, ‘I ain’t never doing that job.’”

He ended up spending 23 years there, working in 90-degree heat, handling molten bars, and wearing cotton long johns to avoid burns.

Despite the brutal conditions, the rink eventually called him back.

A former Clippers teammate who ran concessions at Patterson Park asked Wirth to run a hockey clinic for him in the early 2000s.

Wirth began renting ice on Sunday mornings and Wednesday nights, a routine that lasted five years.

Eventually, he added Saturday mornings and family skate sessions on Sundays, offering both ice hockey matches and figure skating.

When interest in family skates dwindled after three years, his friends encouraged him to stick with the pickup runs — and he’s kept those same weekly ice slots ever since. Wirth’s clinics include 16 to 18 players on average.

These sessions became more than just games for Wirth and his cohort of ex-pros. They evolved into a welcoming community for players of all backgrounds — dubbed the Steve Wirth Hockey League (SWHL).

“We have kids who play college, guys who play professional, and guys who are just rink rats,” Wirth said. “By word of mouth, guys are always giving me a call, and I say, ‘Well, where’d you play? What’d you do?’ So that’s why we continue to grow.”

When the Mount Pleasant Ice Rink opened in 1985, Wirth reconnected with rink operator Dave Stewart, an old friend from his Orchard Ice Rink days. Through that connection, Stewart gave him ice time for his clinics — a tradition that continues today.

Wirth balances the teams himself, and there’s no official referee. With the wealth of experience that the players have, they have no issues keeping the games in check themselves.

“Nobody gives anybody sh*t,” said 65-year-old New York native George Carlson. “It’s a lovely group. Even though obviously hockey is what draws you, it seems like it’s much bigger than hockey for everyone involved. There’s no doubt.”

Carlson grew up playing street hockey in Long Island before pursuing ice hockey in 1974.

He got his start in the New York Met junior B league. Then, he moved on to play in Minnesota and eventually the Pittsburgh Junior Penguins in a junior A league, before joining the Continental Hockey League (CnHL) in Springfield, Illinois.

After that, he played college hockey at Framingham State in Massachusetts. When Carlson transferred to Towson University due to high out-of-state tuition, he joined the Blazers as a goalie to continue playing the sport he loved.

After he completed his psychology degree, he ran into Wirth at a Baltimore Orioles game and connected with him more. Given his passion for the game, it was a natural step for Carlson to join the SWHL.

“He is an upfront, upstanding guy,” Carlson said. “If he weren’t a straight shooter, guys wouldn’t call him. If he was just kind of an a**hole, why would I call him? He’s got a good heart. He may not say that, but he does.”

The SWHL keeps retired players active while giving them a chance to mentor the next generation of hockey players.

Outside the clinics, Carlson recently joined the board of the Baltimore Banners — a youth hockey team managed by mentorship nonprofit organization The Tender Bridge. Every Tuesday, he meets with East Baltimore kids at the Creative Alliance for games and dinner.

“These are young kids who come from very difficult family situations, and hockey’s a ticket to hopefully build those skills,” Carlson said. “It may not be professional hockey, but we’re going to build skills and teach them a new way, a different way.”

The SWHL welcomes anyone who wants to play, including some of Baltimore’s most recognizable names.

In 2019, Orioles vice president assistant general manager of analytics Sig Mejdal — a devoted hockey fan — moved to town and connected with Steve Moorlach, a former Blazers coach and Wirth’s friend.

That link brought Mejdal into Wirth’s clinics.

“The fact that they kept it up for this long is kind of a testament to how important it is to all of them,” Mejdal said. “I’m thinking these old guys are not as fast as the youngsters, but their hockey sense and their skill is apparent.”

For Wirth and his fellow competitors, the goal is simple: keep playing as long as they can.

“As long as I’m physically able, I want to play,” Carlson said. “It’s been a part of my life for more than 50 years. And it’s just a part of my life that I’m not willing to put aside. It brings me great pleasure. So both for my emotional well-being and for my physical well-being, I just feel compelled to keep playing. I don’t see an end. I just don’t.”