LAS VEGAS (AP) — Next week, college football coaches can put the recruiting promises they have made to high school seniors on paper.

Then the question becomes whether they can keep them.

Uncertainty over a key element of the $2.8 billion NCAA antitrust settlement that is reshaping college sports has placed recruiters on a tightrope.

They need clarity about whether the third-party collectives that were closely affiliated with their schools and that ruled name, image, likeness payments over the first four years of the NIL era can be used to exceed the $20.5 million annual cap on what each school can now pay players directly. Or, whether those collectives will simply become a cog in the new system.

Only until that issue is resolved will many coaches know if the offers they’ve made, and that can become official on Aug. 1, will conform to the new rules governing college sports.

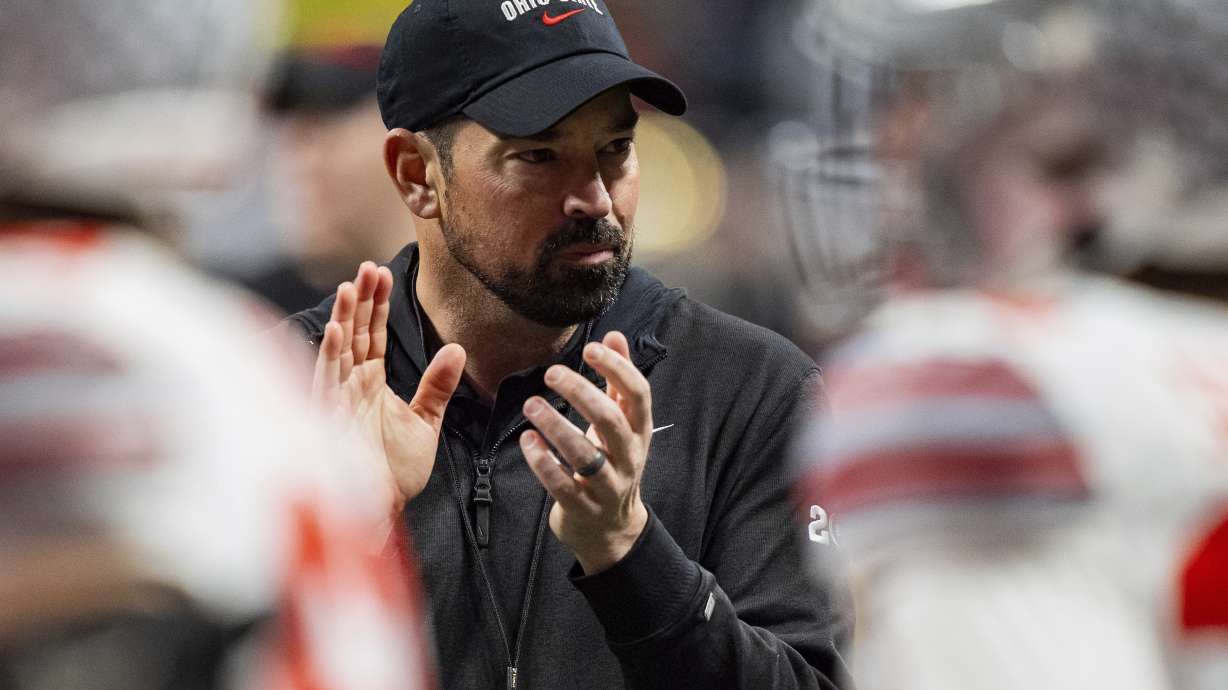

“You don’t want to put agreements on the table about things that we might have to claw back,” Ohio State coach Ryan Day explained at this week’s Big Ten media days. “Because that’s not a great look.”

No coach, of course, is going to fess up to making an offer he can’t back up.

“All we can do is be open and honest about what we do know, and be great communicators from that standpoint,” Oregon’s Dan Lanning said.

Aug. 1 is key because it marks the day football programs can start sending written offers for scholarships to high school prospects starting their senior year.

This process essentially replaces what used to be the signing of a national letter of intent. It symbolizes the changes taking hold in a new era in which players aren’t just signing for a scholarship, but for a paycheck, too.

Paying them is not a straightforward business. Among the gray areas comes from guidance issued earlier this month by the newly formed College Sports Commission in charge of enforcing rules involved with paying players, both through the $20.5 million revenue share with schools and through third-party collectives.

The CSC is in charge of clearing all third-party deals worth $600 or more.

It created uncertainty earlier this month when it announced, in essence, that the collectives did not have a “valid business purpose.” if their only reason to exist was ultimately to pay players. Lawyers for the players barked back and said that is what a collective was always met to be, and if it sells a product for a profit, it qualifies as legit.

The parties are working on a compromise, but if they don’t reach one they will take this in front of a judge to decide.

With Aug. 1 coming up fast, oaches are eager to lock in commitments they’ve spent months, sometimes years, locking down from high school recruits.

“Recruiting never shuts off, so we do need clarity as soon as we can,” Buckeyes athletic director Ross Bjork said. “The sooner we can have clarity, the better. I think the term ‘collective’ has obviously taken on a life of its own. But it’s really not what it’s called, it’s what they do.”

In anticipating the future, some schools have disbanded their collectives while others, such as Ohio State, have brought them in-house. It is all a bit of a gamble. If the agreement that comes out of these negotiations doesn’t restrict collectives, they could be viewed as an easy way to get around the salary cap. Either way, schools eyeing ways for players to earn money outside the cap amid reports that big programs have football rosters worth more than $30 million in terms of overall player payments.

“It’s a lot to catch up, and there’s a lot for coaches and administrators to deal with,” Big Ten Commissioner Tony Petitti said, noting the terms only went into play on July 1. “But I don’t think it’s unusual when you have something this different that there’s going to be some bumps in the road to get to the right place. I think everybody is committed to get there.”

Indiana coach Curt Cignetti, whose program tapped into the transfer portal and NIL to make the most remarkable turnaround in college football last season, acknowledged “the landscape is still changing, changing as we speak today.”

“You’ve got to be light on your feet and nimble,” he said. “At some point, hopefully down the road, this thing will settle down and we’ll have clear rules and regulations on how we operate.”

At stake at Oregon is what is widely regarded as a top-10 recruiting class for a team that finished first in the Big Ten and made the College Football Playoff last year along with three other teams from the league.

“It’s an interpretation that has to be figured out, and anytime there’s a new rule, it’s how does that rule adjust, how does it adapt, how does it change what we have to do here,” Lanning said. “But one thing we’ve been able to do here is — what we say we’ll do, we do.”

AP college sports: https://apnews.com/hub/college-sports