What’s Happening?

The 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports lawsuit will continue for some time. However, many developments will occur along…

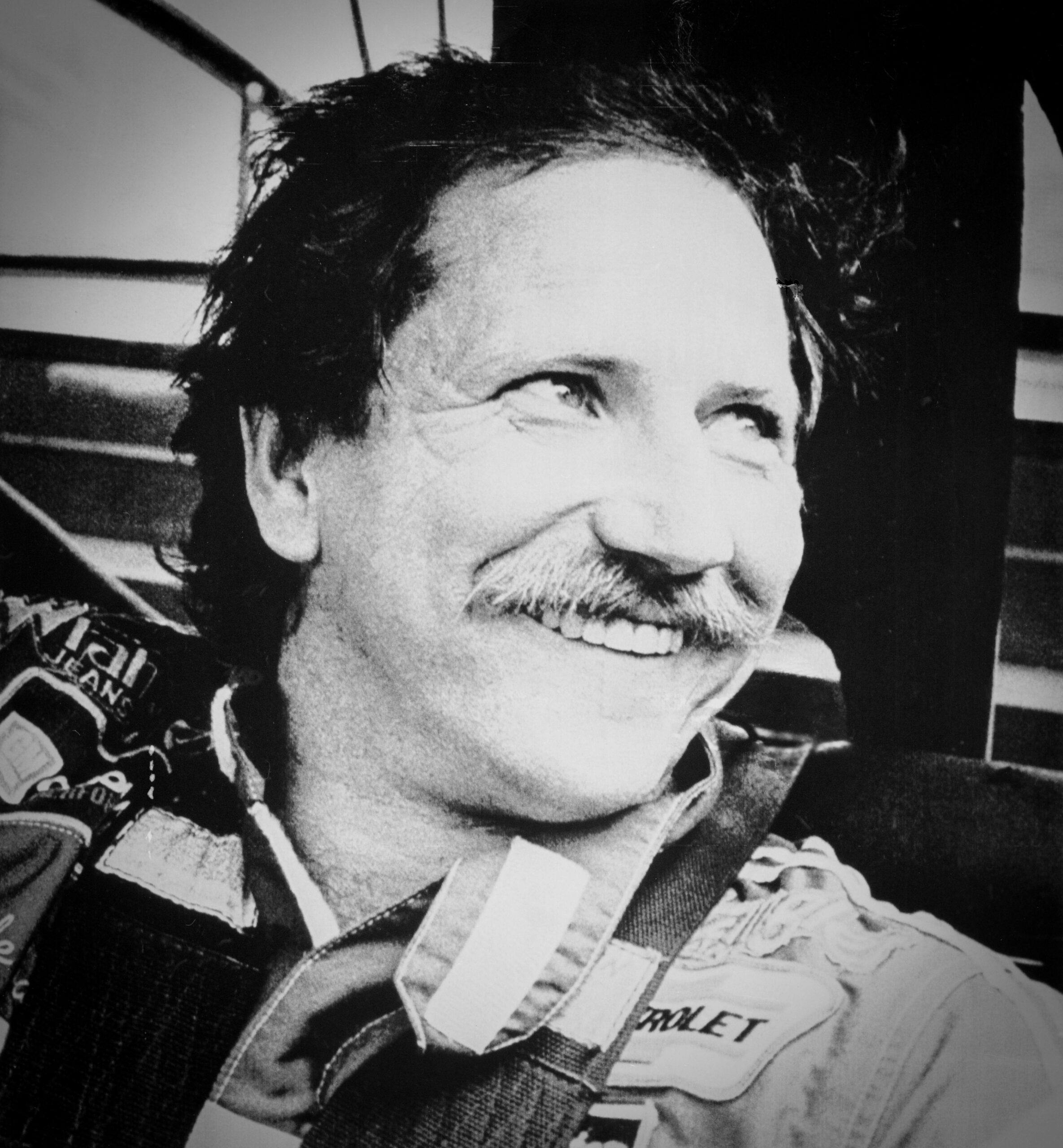

Dozens of sportswriters knew Dale Earnhardt better than I did, or covered him longer. But watching Earnhardt, the four-part documentary now available on Amazon Prime Video, it’s immediately evident that while this program certainly centers around Earnhardt, there are so many ancillary satellites revolving around the main planet, and as part four concludes with an obligatory, sad Willie Nelson song, you click off the remote and think: Man, so much about that time I forgot.

So much about his life, and his death, his friends and his enemies, the way he treated the people he liked, which was different from how he treated his family. How one day Earnhardt started showing up wearing a suit, glamorous third wife Teresa on his arm, became a tycoon, built his Dale Earnhardt, Inc. offices and shop, promptly dubbed the “Garage Mahal,” in 1999. Inside, it was chilly and confusing. Mixed messages abounded. Granite, with gold drinking fountains, plus a stuffed deer that Dale shot, and the shotgun he used to kill it. So many shiny trophies that, lumped together, sort of lose meaning. It reminded me of Graceland.

Let’s face it: We all know how this movie ends, in a comparatively innocuous-looking crash on the last lap of the 2001 Daytona 500. So you’re signing up to watch a four-hour documentary because you are either interested in NASCAR in general, Dale Earnhardt in particular, or you just enjoy a well-told story.

The documentary, executive-produced by Ron Howard and his longtime business partner, Brian Grazer, will win awards, and it deserves to: I’ve worked on projects like this, and through all four parts I marveled at the precise footage and perfect soundbites the production team was able to unearth, because I know for every minute of aired footage, they must have had to plow through hours and hours of archives, beg friends and families and fans for home movies, refuse to take no for an answer when they knew what they needed exists, out there somewhere.

You don’t have to be a race fan to appreciate Earnhardt, though it helps, especially if you’ve been around for a while.

I met Dale Earnhardt on November 19, 1989, at what was then the Atlanta International Raceway. It was the Winston Cup season finale—and isn’t that the smartest marketing you ever saw, when you had to actually say the name of a cigarette company when you were referencing the series?—where the ’89 champion would be crowned. I was covering it for the Dallas Times Herald. It was my first NASCAR race. I wasn’t a Times Herald sportswriter; I was actually the paper’s television critic, and I had timed a visit to CNN studios to write a feature on the news network’s upcoming 10th anniversary for an airline magazine (remember those?). It was not a coincidence that there was an important NASCAR race there that weekend—I’d been writing about motorsports for a while, and it came time for me to check that NASCAR box.

So I joined 15 or 20 actual sportswriters in the Atlanta track’s small infield press room, accompanied by nobody I knew, but several I’d heard of. I was not accustomed to being in a room that had no view of the actual racetrack, but soon learned that wasn’t unusual.

It was not a particularly eventful race, until lap 202, when the orange number 22 car of journeyman driver Grant Adcox pancaked the outside wall and burst into flames as the car traveled down the embankment, into the infield. It seemed to take forever to get Adcox out of the car: They had to use the Jaws of Life to cut off the roof. He was taken to the infield care center, then helicoptered to an Atlanta hospital. There’s little question that Adcox was dead before his car stopped rolling, as the mounting for his seat came loose in the impact, and unrestrained, he suffered fatal head and chest trauma, but it is typical of all forms of motorsports to transport the driver to the hospital, where the family can gather and an appropriate member of the clergy breaks the news, and the carefully structured official announcement is made later, so fans can leave unaware that they’d just seen someone die. To a T, that script would be followed 12 years later for Earnhardt himself.

Adcox worked with his father at Herb Adcox Chevrolet in Chattanooga. He never had enough money to compete full-time in NASCAR, but raced regularly in the ARCA series, which used older Cup cars. Dale Earnhardt had said in an interview earlier in the season that he was impressed with Adcox’s talent, and with enough money, maybe he could be a success in the Cup series.

Some of the Cup races Adcox had managed to run seemed cursed. In 1974, Adcox qualified for a race at Talladega Superspeedway. Midway through the event, the caution flag flew, and the drivers dashed for pit road. As he started to pull into his pit stall, Adcox’s car began to slide, right into Gary Bettenhausen’s Roger Penske–owned AMC Matador, which was being serviced by the crew. Several of them were struck and injured, the worst being Don Miller, who lost a leg.

The following year, Adcox again qualified for the race at Talladega, but his crew chief dropped dead from a heart attack right there in the garage. The car was withdrawn, but Adcox found another ride, and then the race was delayed a week by rain. Adcox, a working man, had to cancel, and his spot in the field was given to fan favorite Tiny Lund, the affable 6-foot, 5-inch, 270-pound winner of the 1963 Daytona 500. In a multi-car crash on lap seven, Lund’s car was struck broadside, and he was killed. He was 45. Had Adcox been able to race, Lund would have been watching from the grandstands.

Earnhardt won that race at Atlanta, though he lost the 1989 championship to Rusty Wallace. Earnhardt was cheerful when he came into the press room to talk to us: One of his first comments was, “Boy, I hope Grant’s OK. That was a hard hit he took.” A sportswriter sitting next to me leaned over and whispered, “Did nobody tell him?”

Apparently not, and we sure didn’t. I spoke to Earnhardt briefly, then was soon back in my hotel room, about to type out the story on my wretched Radio Shack TRS 80 laptop. But what was my lede? That Earnhardt won? That Wallace was the champion? That Adcox was the first Cup driver to die in five years? I don’t recall what I typed into the Trash 80, but I typed away. And I had covered my first NASCAR race.

As I went to more and more races, Earnhardt was always a looming presence. He was hated and adored. I fell somewhere in between. Rubbing may be racing, but Earnhardt’s aggressiveness often rubbed me the wrong way, especially earlier in his career. He was polarizing—you either got him or you didn’t.

I apologize for the above autobiography, and I need to get back to Earnhardt. The praise is deserved, and the use of film and clips from TV broadcasts is Emmy-worthy. The TV critic in me was a little put off by the staging of some of the present-day interviews: It isn’t unusual for the interviewer, unseen and unheard in this case, to tell the subject to look at me, not at the camera, but several of the subjects appear to be speaking to someone in another room. The interviews with bass fishing legend Hank Parker, an Earnhardt confidant, are so dark and distant it’s almost like he was being filmed by a hidden camera. But that would be nitpicking director Joshua Altman’s style. Taken as a whole, Earnhardt is top-shelf. Part three drags a bit, but the rest seem right-sized.

As I watched, I took notes. Following are some expansions on those notes, in no particular order, which fans of the man and the documentary might find of interest.

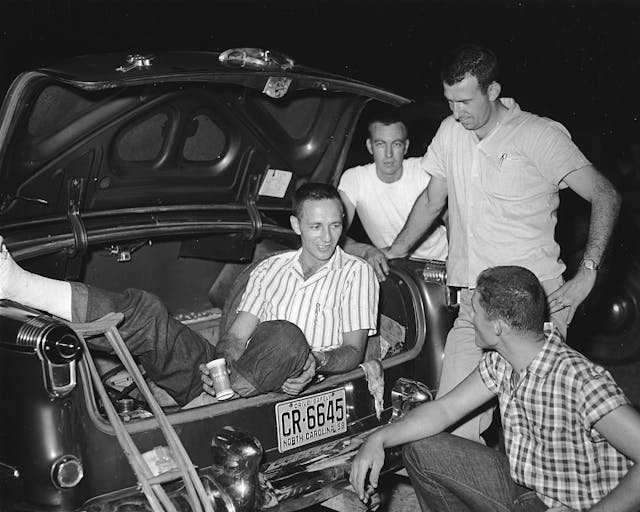

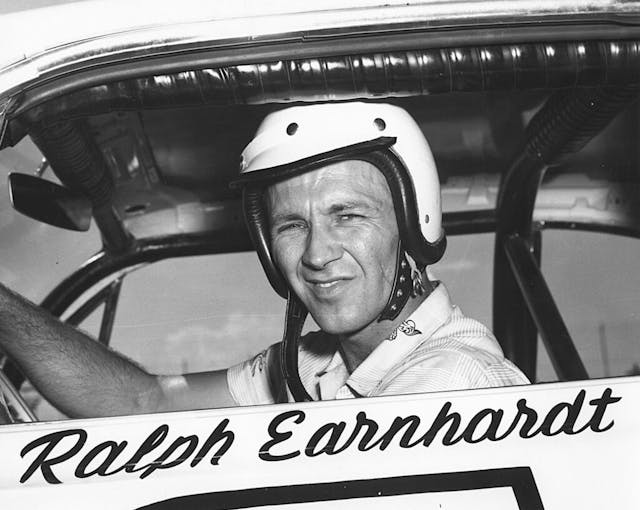

I wanted more from Earnhardt about Ralph Earnhardt than we were served. The importance he played in his son Dale’s life, perhaps not so much by action as inaction, was telling at every turn. Growing up at racetracks in the south, I’d seen dozens of Ralph Earnhardts: Lean, hard-bitten, tanned, wary and suspicious, usually with a pack of Lucky Strikes tucked in their shirt pocket. Ralph was a talented driver, perhaps an even more talented car- and engine-builder, as often as not working for the drivers he competed against on Saturday nights.

Ralph toiled for years in cotton gins, looking for a way out. That would be racing. With his typically German meticulous, practical personality, he wanted more, but didn’t crave it, didn’t demand superstardom, didn’t much want to travel, but he dominated racing for years at local tracks, where he made enough money and got to sleep in his own bed every night. He was sick most of 1973 with heart trouble, had to let his friend Stick Elliott race his car, but was back behind the wheel that summer, and won two races at Concord Speedway. “Veteran Ralph Earnhardt is back in high gear,” said the Charlotte News in July.

Two months later, Ralph Earnhardt died, at home, from a heart attack. He was 45. Years after, Dale spoke about his father in an interview. “That’s the last funeral I’ve ever gone to. It took me a year or so to get over being mad. I felt like I was robbed. I felt hurt,” Dale said. “It was too tough to take. The memories. All the things I wanted to tell him.”

Which, we learn from Earnhardt, isn’t at all dissimilar from the way Junior felt after losing his father, who was 49.

Teresa Houston was pretty, and she knew it. She had grown up around racing—her uncle is Tommy Houston, who had 24 wins and 198 top-10 finishes in the NASCAR Busch series, and her cousin Andy Houston raced in all three of the major NASCAR series. She naturally met Earnhardt at the track, and they married on November 14, 1982.

She wanted to be a mother—her daughter Taylor Nicole was born on December 20, 1988—but she wasn’t crazy about being a stepmother. The relationship between her and Dale’s other kids, son Kerry, daughter Kelley, and Dale Earnhardt, Jr., was icy from the start. Kerry related on Dale Jr.’s podcast that when he was finally invited to his father’s house for the first time—at age 16—Teresa slammed the door in his face.

It may seem that Teresa, now 66, has been unfairly painted as the evil stepmother, but she certainly hasn’t helped her own cause. She virtually disappeared after Earnhardt was killed. She inherited everything: The Garage Mahal, the race teams, so much property, and the spectacularly profitable souvenir business.

Kelley, Kerry, and Dale Jr. got nothing, not even their own names. When Kerry and his wife Rene signed a deal with Schumacher Homes to help design and promote new houses, they called it the “Earnhardt Collection.” The ads were benign, in no way suggesting that Dale Earnhardt or his estate had anything to do with the project. Nonetheless, Teresa filed suit against her stepson in 2017, contending that Kerry, by using the name he was born with, was infringing on her copyright. Kelley and Junior were properly appalled, but not surprised. The case dragged on for years. It’s difficult to even conceive of a reason why Teresa would do this, aside from spite.

It’s worth noting, too, that Teresa had Senior buried on “her” land, and Junior revealed in a very recent Washington Post interview that he has only been able to visit his father’s grave once since he died, because Teresa has forbidden him and Kelley to access her property. Which may or may not be legal, given North Carolina’s confusing laws pertaining to whether or not a property owner can legally bar the next of kin from a gravesite.

With the possible exception of Brooke Sealey, Jeff Gordon’s first wife, no NASCAR ex has maintained a lower public profile than Teresa. Her name was most recently in the news last October, when she revealed plans for a portion of what the Charlotte Observer called her “vast landholdings.” The paper reported that she had asked the local planning board to rezone 399 acres in Mooresville so she could build an industrial park.

Earnhardt mentioned that Dale Jr. continued to race for the now-Teresa-owned Dale Earnhardt, Inc., until 2007, when the situation just became untenable. After his move to Hendrick Motorsports, sponsors fled DEI, and Teresa had to merge with Chip Ganassi Racing in 2008.

The extent to which Teresa is reviled by so many NASCAR fans wasn’t fully explored in Earnhardt, nor was her toxic relationship with her three stepchildren. It’s just so sad.

No one is more surprised than I am that I’m describing Junior as a deeply complex man. In his younger years, that would have seemed absurd: What’s so complex about a kid who loves pickup trucks and beer and video games, and hanging out with his buddies, and who very possibly could have found happiness working forever at his father’s Chevrolet dealership?

One thing Earnhardt puts in laser focus was Junior’s need to earn his father’s respect, and he saw racing as being the road to that. Despite being a very wealthy man, Senior repeatedly balked at helping his children race, ostensibly because he wanted them to experience the same maturing desperation that he met and eventually conquered.

Hank Parker says in Earnhardt that he convinced Dale to spend some money helping them out, and Senior did buy them each a late-model car to run at local paved ovals, and a truck and trailer to haul them around in. It’s downright stunning when Junior says that he raced in 159 late-model races, and his father never came to a single one. Junior knew nothing about racecraft, and the man who possibly knew more about it than anyone declined to teach him.

Still, Junior battled through all that to win races—and a burgeoning fan base. When he moved to Hendrick, many of us thought he had it made, but Junior struggled. He had the same equipment Jimmie Johnson and Jeff Gordon did, but they were winning championships and he wasn’t. After a colleague and I interviewed him during the now-defunct NASCAR media tour, we walked away disheartened by how sad Dale seemed. I asked him if he felt he had good chemistry with his current crew chief, and he said, “I’m not sure I’ve ever had good chemistry with a crew chief. I don’t even know what that is.” NASCAR drivers just don’t say things like that to reporters holding tape recorders. Afterward, my friend suggested, not entirely kidding, that Hendrick needed to put him on suicide watch.

When Dale Jr. retired at the end of the 2017 season, he had amassed a very respectable record: 26 wins, two of them the Daytona 500, with 260 top-10s in 631 races.

He and Kelley formed JR Motorsports, which in 2016 began fielding NASCAR Nationwide (now Xfinity) series cars, with the help of Rick Hendrick. The team began winning that first year and hasn’t stopped. Sponsors are delighted to bask in Junior’s company, and he and Kelley seem really happy in their respective roles.

Junior was one of NASCAR’s early adopters when it came to social media, founding the Dale Jr. Download in 2013, with Junior becoming the regular host in 2017. The podcast added video, and as Earnhardt honed his skill as a broadcaster, the Dale Jr. Download has become possibly the single most influential media source there is in the racing world—not just NASCAR, as Junior can and does have guests from all forms of racing. The way Howard Stern can get celebrities to emotionally expose themselves in a way they won’t anywhere else, racers will reveal parts of their lives to Junior that would typically be off limits elsewhere.

Never has Junior seemed so comfortable in his own skin. Years ago, I said this on a radio show that I hosted: If any racer had a license to be an asshole, it’s Dale Earnhardt, Jr. But he isn’t. In person, he’s polite, interested in what you have to say, patient with fans wanting autographs and selfies, and a genuinely nice guy.

I think that comes across in Earnhardt. Because the documentary is supposed to be about Senior, but Junior carries the day. Good for him, and Kelley, and Kerry.

23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports’ antitrust lawsuit filed against NASCAR over a year ago, and while the lead-up to the trial had plenty of revelations, the nine-day trial also had its fair share of breaking news. Here are five unforgettable things we learned from the 23XI/FRM and NASCAR antitrust trial.

What’s Happening?

The 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports lawsuit will continue for some time. However, many developments will occur along…

On day one of the trial, 23XI Racing co-owner Denny Hamlin came out swinging right out of the gate, accusing NASCAR of being the reason that Germain Racing, which operated a Cup Series team from 2009 to 2020, went out of business.

Hamlin alleged that NASCAR, as part of its Premier Partners program, which the sport introduced in 2020 to replace its then-departed title sponsor Monster Energy, brought on GEICO, taking the long-time sponsor partner away from Germain.

What’s Happening?

During the first day of 23XI Racing/Front Row Motorsports and NASCAR’s antitrust trial, 23XI Racing co-owner and NASCAR veteran…

During his cross-examination of Hamlin, NASCAR’s lawyer asked Denny Hamlin about a text message he sent to 23XI Racing co-owner Michael Jordan. In this text from 2023, Hamlin asked Jordan to find a buyer for his portion of 23XI.

While Hamlin did not, and has not, sold any portion of 23XI, the owner/driver claims this during a period of frustration and needed to get the attention of his business partners. Hamlin also says he and his fellow co-owners resolved this issue in a meeting at Jordan’s golf course, The Grove XXIII.

What’s Happening?

During a multi-hour cross-examination of 23XI Racing co-owner Denny Hamlin, NASCAR’s legal team revealed messages suggesting that in 2023,…

Every NASCAR fan knows the tragic story of Furniture Row Racing, which, after winning the 2017 NASCAR Cup Series Championship, closed its operation at the end of the 2018 season. Prior to this lawsuit, it was widely known, but unconfirmed by the sport or parties involved, that their closure was for financial reasons related to an increased alliance with Joe Gibbs Racing.

Shockingly, during this trial, NASCAR’s legal team accused JGR of being the reason FRR closed its door, with attorney Lawrence Buterman alleging the team doubled the price of the partnership after their title win on Monday. Even more shocking was the testimony of NASCAR Commissioner Steve Phelps, who claimed that JGR didn’t just double the price, but tripled it from roughly $3 million to $10 million.

What’s Happening?

NASCAR’s legal team claims that one specific factor contributed to the closure of the fan favorite team, Furniture Row…

Though many were excited for Richard Childress to take the witness stand, the resulting testimony and examination did not mention the hot-button issue of comments made by NASCAR Commissioner Steve Phelps in text messages unsealed by the courts.

But that doesn’t mean his time in the courtroom wasn’t without fireworks, as the court revealed that Childress only owns 60% of RCR and that NASCAR was aware of a group led by former driver Bobby Hillin Jr., who had attempted to buy RCR.

This questioning led to an “animated” response from Childress, who said that the deal had fallen through and was confused how NASCAR had known this due to an NDA he had Hillin and members of the interested party sign prior to negotiations.

What’s Happening?

During a heated portion of Richard Childress’s examination in the ongoing NASCAR antitrust trial, NASCAR’s attorney revealed that Childress…

During the examination of NASCAR Chairman and CEO Jim France, 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports lawyer Jeffery Kessler read a letter sent by team owner Rick Hendrick to France in early 2024.

In this letter, Hendrick asked France to consider “a Charter agreement that’s fair and ensures a collaborative and prosperous structure for NASCAR, its stakeholders and the industry as a whole.“

Hendrick also made two specific claims in his letter.

First, he claimed that NASCAR had told teams, “bring no value, our rights are worthless, and we don’t know how to run a viable business.” Second, he claimed that despite success on track, including two Championships, the team had lost tens of millions of dollars over the prior five seasons.

While Hendrick’s in-profitability, like several other revelations in the trial, was no secret, the fact that one of the sport’s most successful and perhaps most popular teams lost $20 million over five seasons astounded the NASCAR fan base.

What’s Happening?

During the Tuesday afternoon examination of NASCAR CEO Jim France, 23XI Racing, Front Row Motorsports lawyer Jeffery Kessler presented…

What do you think about this? Let us know your opinion on Discord or X. Don’t forget that you can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube.

The festival, launched on 12 December 2025, features adventure activities, speed challenges, live music, and cultural and entertainment experiences for all family members. Running until 3 January 2026 amid the golden dunes of the Al Dhafra Region, the festival has become a major winter attraction.

It draws people of all ages, nationalities, and cultures, blending heritage with adventure around Tal Moreeb—the UAE’s tallest sand dune at 300 metres. Since 2001, the festival has grown into one of the region’s premier winter destinations, attracting camping enthusiasts, adventure seekers, and fans of traditional sports with a diverse programme for all age groups.

The festival opened with an aerial show by the UAE Falcons Aerobatic Team, the official aerobatic display team of the UAE Air Force, accompanied by fireworks, drone shows, and spectacular light performances that illuminated Liwa’s skies.

Liwa Desert is a regional motorsports hub during winter, hosting events such as the Freestyle Show (12–13 and 22–23 December 2025), the Spartan Liwa Race (13 December 2025), and today’s Bike Drag Race (14 December 2025).

Liwa Village offers family-friendly entertainment, including water karting, carnival and skill games, zip-lines, a Classic Cars Museum, an escape room, a rage room, and pony and petting zoos. This edition also features a traditional handicraft market, live music, cultural performances, and a mix of Emirati and international cuisine.

The festival promises an unforgettable New Year’s Eve with a special concert and fireworks over the Liwa Desert. The Tal Moreeb Motorsports Championship also runs from 31 December 2025, giving speed enthusiasts an adrenaline-filled farewell to 2025 and a thrilling start to 2026.

The Liwa International Festival 2026 highlights traditional Emirati sports, including the Falconry and Hadd Al-Hamam Championships, and showcases crafts at Liwa Market, strengthening the community’s connection to its culture.

Visitors can book luxury tents, stay in local accommodations, or camp in the Al Dhafra Desert, enjoying a unique experience amid the golden dunes.

Abdullah Rashid Al Hammadi is an accomplished Emirati journalist with over 45 years of experience in both Arabic and English media. He currently serves as the Abu Dhabi Bureau Chief fo Gulf News.

Al Hammadi began his career in 1980 with Al Ittihad newspaper, where he rose through the ranks to hold key editorial positions, including Head of International News, Director of the Research Center, and Acting Managing Editor.

A founding member of the UAE Journalists Association and a former board member, he is also affiliated with the General Federation of Arab Journalists and the International Federation of Journalists. Al Hammadi studied Information Systems Technology at the University of Virginia and completed journalism training with Reuters in Cairo and London.

During his time in Washington, D.C., he reported for Alittihad and became a member of the National Press Club. From 2000 to 2008, he wrote the widely read Dababees column, known for its critical take on social issues.

Throughout his career, Al Hammadi has conducted high-profile interviews with prominent leaders including UAE President His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, HH Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, and key Arab figures such as the late Yasser Arafat and former presidents of Yemen and Egypt.

He has reported on major historical events such as the Iran-Iraq war, the liberation of Kuwait, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority. His work continues to shape and influence journalism in the UAE and the wider Arab world.

The second round of the 2025/26 Asian Le Mans Series at Sepang International Circuit delivered another dramatic four-hour endurance battle on Sunday, December 14, heavily influenced by unpredictable Malaysian weather. After claiming victory in Saturday’s opener, Cetilar Racing’s #47 Oreca 07-Gibson crew of Roberto Lacorte, Charles Milesi, and Antonio Fuoco dominated proceedings to secure a weekend double, finishing ahead of the field when the race was red-flagged with approximately 20 minutes remaining due to torrential rain flooding the track.

–by Mark Cipolloni–

The race featured multiple interruptions, including three periods behind the Safety Car or Virtual Safety Car and two full-course yellows, as teams grappled with shifting conditions and tire strategy. Competitors were circulating on slick tires behind the Safety Car following an earlier incident when the heaviest downpour hit, rendering the circuit undriveable and prompting race control to halt proceedings prematurely.

Cetilar Racing controlled much of the race after taking the lead in the second hour. A key moment came when Antonio Fuoco overtook Tom Dillmann in the #25 Algarve Pro Racing Oreca on a restart, pulling away to build a comfortable margin—eventually over 30 seconds—before the red flag sealed their second win in as many days. Algarve Pro Racing held on for second, with the #4 Crowdstrike Racing by APR Oreca completing an identical LMP2 podium to Race 1.

In the LMP3 class, a bold strategy propelled CLX Motorsport’s #17 Ligier JS P325 to the top step. Driver Paul Lanchere—fresh off his European Le Mans Series title success—served the two mandatory 100-second pit stops during an early Virtual Safety Car period, a calculated risk that paid dividends as conditions evolved. The Swiss outfit capitalized to claim victory, with Lanchere sharing the podium with teammates Kevin Rabin and Alexander Jacoby.

The #71 23Events Racing Ligier finished second, ahead of the #29 Forestier Racing by VPS entry in third, rounding out a competitive class battle in the debut season for the new-generation LMP3 machinery.

Kessel Racing secured maximum points in the hotly contested GT class, overcoming a grid penalty to triumph with their Ferrari 296 GT3. Dustin Scott Blattner made rapid early progress, climbing from 15th to third in the opening laps, before astute tire calls allowed Chris Lulham and Dennis Marschall to surge into the lead and stay there amid the chaos.

The #69 Team WRT BMW M4 GT3 delivered a strong recovery after an overnight engine change addressed power issues from Race 1, with Tony McIntosh, Parker Thompson, and Dan Harper taking second. Third went to the #87 Origine Motorsport Porsche, where Bo Yuan impressed with blistering pace during a long stint, charging from 14th and briefly challenging for the lead.

The Asian Le Mans Series now heads to the United Arab Emirates for the next double-header, with the 4 Hours of Dubai scheduled for January 31 and February 1, 2026.

03_Classification_Race 2_FINAL

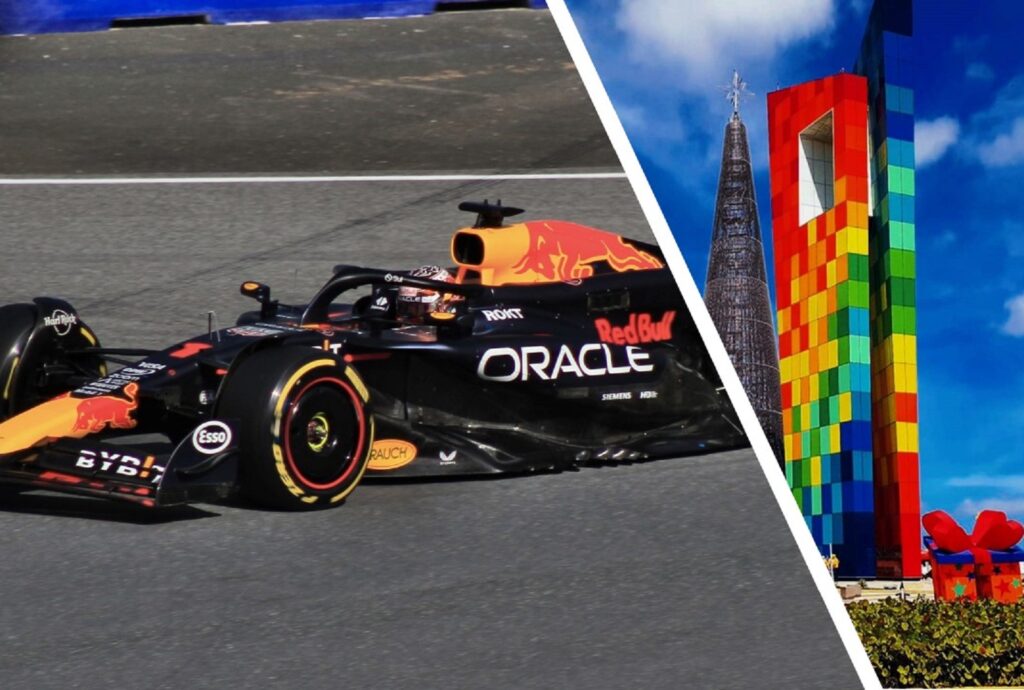

Barranquilla is reviving its long-held dream of hosting a Formula 1 Grand Prix for Colombia. The local administration, led by Mayor Alejandro Char, has announced the reactivation of the city’s bid to join the world championship motorsports calendar—an objective that would combine sporting spectacle with a major economic and tourism boost for the region.

Despite differences with President Gustavo Petro’s national government on the issue, the mayor said yesterday that the project depends solely on his administration and that state approval is no longer required. With this, the aspirations of the capital of Colombia’s Caribbean region are being renewed and are now framed under a logic of municipal autonomy and the direct interest of Formula 1 organizers in exploring alternatives in emerging markets.

In the most recent talks, Formula 1 delegates visited Barranquilla to assess the city’s potential as a race host, focusing on a semi-urban circuit running along the Magdalena River and connecting with the Gran Malecón. This renewed push comes at a time when the city is drawing attention for other international bids—such as hosting the 2026 Copa Sudamericana final—and is seeking to establish itself as a hub for global events in the Caribbean region.

The possibility that top-tier single-seaters could race on Colombian soil has reignited interest and expectations among government officials, business leaders, and fans alike, sparking a debate over what it would mean for Barranquilla and for Colombia to open a new chapter in the history of motorsports.

Barranquilla’s aspiration to host a Formula 1 race did not emerge overnight. The project has its roots in earlier efforts, when under the administration of then-mayor Jaime Pumarejo concrete possibilities were explored to bring the championship to the city.

During that stage, there were direct conversations with representatives of the category, and possible semi-urban layouts were designed around the Magdalena River waterfront. Even figures linked to motorsport and to the organization expressed enthusiasm for Barranquilla’s potential as the venue for a “Caribbean Grand Prix.”

However, political and logistical factors at the time stalled the project’s realization, and the lack of an official letter from the national government was perceived as a key obstacle. Today, with an administration determined to take the reins of the process, that barrier has shifted.

Mayor Char has emphasized that progress on the bid now depends almost exclusively on agreements between the Mayor’s Office and Formula 1 organizers, without requiring direct approval from the national executive branch. This municipal autonomy is seen as a strategic advantage, capable of speeding up negotiations and presenting a proposal that is more agile and better tailored to the category’s needs.

Despite the enthusiasm and interest shown by Formula 1 representatives, not all aspects of the project are straightforward. Among the most frequently cited drawbacks by the Barranquilla administration is the city’s airport infrastructure. The international airport serving Barranquilla, Ernesto Cortissoz, has been identified as insufficient to meet the demands of an event on the scale of a motor racing Grand Prix.

Formula 1 delegates, according to statements by the mayor, have indicated that the current conditions of the air terminal and its facilities do not meet expected standards, raising the need for investments or significant improvements in this area.

Beyond logistical challenges, the project’s backers defend its economic potential. Formula 1 is far more than a race; it is a magnet for high-spending tourism, global sponsorships, international media coverage, and urban development. Cities such as Miami have shown how the presence of the top tier of motorsport can transform a destination’s international perception and attract investment.

For Barranquilla, a Grand Prix would mean not only an expansion of its sports and cultural offerings, but also a direct impact on sectors such as hotels, restaurants, commerce, and services, with the arrival of thousands of visitors over a race weekend.

Preliminary proposals for the circuit in Barranquilla envision a semi-urban layout that takes advantage of distinctive features of the city: its geography, its waterfront, and its proximity to the Magdalena River. The idea of a circuit that runs through emblematic areas, rather than a traditional closed track, seeks to create a unique experience for both drivers and spectators.

This connection with the urban and natural environment could be one of the attractions that appeal to Formula 1, which in recent years has shown interest in diversifying its venues and exploring new markets.

The dream of organizing a Grand Prix in Barranquilla still faces many challenges ahead, from technical and financial agreements to improvements in key infrastructure. However, the reactivation of the bid under a locally driven approach conveyed by Mayor Char has renewed expectations and placed Barranquilla once again in the international conversation of motorsport.

If the proposal continues to move forward, the roar of the engines could become yet another symbol of the city’s Caribbean ambition to establish itself on the map of major global events.

In the high-stakes world of NASCAR Cup Series racing, where billions in revenue swirl around media deals, sponsorships, and the all-important charters that guarantee a team’s spot in every race, most owners play it safe. They sign on the dotted line, grumble privately, and keep the peace with the France family empire. But in late 2024, two teams decided enough was enough.

–by Mark Cipolloni–

23XI Racing—co-owned by NBA legend Michael Jordan and driver Denny Hamlin—and Front Row Motorsports (FRM), led by Bob Jenkins, refused to sign NASCAR’s “take-it-or-leave-it” charter extension for 2025-2031. While 13 other teams reluctantly inked the deal, fearing the loss of their valuable franchises, 23XI and Front Row filed a bombshell antitrust lawsuit, accusing NASCAR of monopolistic practices that stifled team growth and funneled too much profit to the sanctioning body.

It was a gutsy move. They raced much of 2025 as “open” teams, forfeiting millions in guaranteed revenue. The trial in Charlotte dragged on for weeks, exposing embarrassing texts, tough negotiations, and the raw power dynamics of the sport. Many in the garage whispered that the rebels were risking it all—for what?

Then, on December 11, 2025, everything changed. Midway through the trial, a settlement was announced. NASCAR blinked.

The deal handed all 15 chartered teams “evergreen” charters—essentially permanent franchises that don’t expire, making them true assets like NFL or NBA teams. Overnight, industry experts estimated charter values could double, from recent sales around $45 million to potentially $90-100 million each. Teams gained shares of international media rights (previously zero for them), a cut of new intellectual property deals, reinstated governance input via an expanded “strike” rule, and more.

The other 13 teams? They got all these upgrades without spending a dime on lawyers, without missing a single purse payout, and without ever sticking their necks out during negotiations.

Although none of the other team owners said, they all had to be thinking, ‘We signed because we felt we had no choice. Those two fought the fight we were all too scared to wage—and now we’re all richer for it.’

The irony wasn’t lost on anyone. The teams that played it safe, signing the original deal under duress, now reap the biggest rewards thanks to the ones who had the balls to sue.

Denny Hamlin captured the resolve behind the fight: “Standing up isn’t easy, but progress never comes from staying silent. The reward is in knowing you changed something.”

Michael Jordan emphasized the broader impact: “From the beginning, this lawsuit was about progress. It was about making sure our sport evolves in a way that supports everyone: teams, drivers, partners, employees, and fans.”

Hamlin added that the outcome is “going to grow the sport, and it’s going to be better for everyone, there’s no doubt about it.”

Other team owners welcomed the resolution. Rick Hendrick stated: “Today’s resolution allows all of us to focus on what truly matters—the future of our sport. When our industry is united, there’s no limit to how far we can go or how much we can grow the sport we love.”

Roger Penske called it “tremendous news for the industry.”

As ESPN’s Ryan McGee noted, every team once stood united with 23XI and Front Row during negotiations but eventually lacked the balls and signed—leaving the two to carry the fight alone. “They won that fight, and as a result, so did every NASCAR team owner who is fortunate enough to have one of those 36 charters.”

Former NASCAR driver and now pudit, Kenny Wallace, predicted what the settlement by NASCAR could imply for the teams and why it could be game-changing.

Shortly after the announcement, Wallace spoke to the camera, where the 62-year-old shared his thoughts and seemed rather pleased with the turn of events.

Wallace believed 23XI Racing and FRM had gotten what they sought and hence decided to settle. He also presumed that the settlement would translate to more TV revenue and evergreen charters for the teams.

According to Wallace, NASCAR’s leaked letters and the overall fan sentiment prompted the governing body to pursue the settlement route further. He also pointed out that NASCAR bosses’ unwillingness to answer tough questions only weakened the governing body’s case.

For their efforts and fortitude, NASCAR will pay 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports an unknown amount of monetary damages and legal fees.

With permanent charters now in place, the entire Cup Series field reaps enhanced stability and value, courtesy of the two teams that refused to back down. The garage moves forward united, poised for growth in 2026 and beyond.

The overwhelming influence of sponsors in NASCAR became evident during the recent charter agreement fiasco. Teams would face significant challenges in operating and covering their expenses without the substantial real estate opportunities provided by their cars. But seldom do these sponsors, which are often large enterprises, stick to a single team or driver.

Dave Alpern explained why in a video posted by the team on their YouTube handle. He went, “Some sponsors within an organization like to be a family of drivers versus one. Interstate Batteries is a great example.

“Interstate for many years was just on our famed No. 18 car. Now, they try to do at least one race with all of our drivers.”

They also have an associate sponsor logo on all of the team’s cars throughout the season. This is just a marketing strategy that the company employs to have visibility during races and associate itself with one particular well-performing team. Other companies don’t necessarily follow this same approach.

Alpern continued, “There are also brands that choose to sponsor multiple times. I think of Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola has a family of different drivers across a bunch of different organizations. Their goal being, they want a winning driver to get out and swig a Coke. The more drivers they have, they feel like that meets their strategy.”

And then, there are companies like Bass Pro Shops. The sporting goods retailer not only sponsors races, but it is also associated with a bunch of different teams. It has strong relationships in the garage with multiple teams and drivers, with a wide reach of sponsorship. The point to be made is that there is no right or wrong in this facet of the sport.

“It kind of just depends on the brand and what their objectives are. But yeah, it’s more common to see one sponsor paired with one driver and car number. But it’s not uncommon to see them spread across multiple cars,” the Joe Gibbs Racing President added.

Race cars are essentially moving billboards for companies, and the ultimate goal is to catch the eye of the passionate fanbase.

Moreover, sponsoring a single car and driver can be a risky gamble. The driver could get injured or perform poorly throughout the season. This would hurt the image of the sponsor heavily and go against their end goal.

Fargo girl, 13, dies after collapsing during school basketball game – Grand Forks Herald

CPG Brands Like Allegra Are Betting on F1 for the First Time

Two Pro Volleyball Leagues Serve Up Plans for Minnesota Teams

Utah State Announces 2025-26 Indoor Track & Field Schedule

Sycamores unveil 2026 track and field schedule

Redemption Means First Pro Stock World Championship for Dallas Glenn

Jo Shimoda Undergoes Back Surgery

Texas volleyball vs Kentucky game score: Live SEC tournament updates

Robert “Bobby” Lewis Hardin, 56

How this startup (and a KC sports icon) turned young players into card-carrying legends overnight