Miguel Ángel Jiménez easily beats the clock in the European Tour’s 2018 Shot Clock Masters in Austria. Matthew Lewis, Getty Images MLB’s competition committee had seen enough evidence as well to vote for implementing a pitch clock – amended to 15 and 20 seconds depending on baserunners and by the eight-second mark for batters to […]

MLB’s competition committee had seen enough evidence as well to vote for implementing a pitch clock – amended to 15 and 20 seconds depending on baserunners and by the eight-second mark for batters to be in position – for the 2023 season.

Golf, on the other hand, has only recently placed a specific value on how much time it should take to play a shot. In the 2019 update to the Rules of Golf, 40 seconds was recommended as the upper boundary before reaching what constitutes “undue delay.”

Perhaps the time has finally come to make that wish a reality.

Golf could follow baseball’s example and begin experimenting with shot clocks in its developmental leagues – the Korn Ferry Tour, PGA Tour Americas or Europe’s HotelPlanner Tour. Maybe one tour can test it only around the greens while another tries it through the course to figure out what works best and most efficiently. Only by trial and error can it be honed, perfected and ultimately implemented on the PGA Tour.

The rules were pretty simple:

It was a win-win.

Baseball games in 1901 averaged only 1 hour, 47 minutes for nine innings and the average remained under two hours as late as 1944. It hit 2:30 in 1959, crossed the three-hour mark in 2014 and by 2021, that average time ballooned to a peak of 3 hours, 11 minutes. Along the way, the debate over the pace of play rose and fell repeatedly.

“I’ll play as slow as I damned well please,” Walker once famously said.

Obviously, it would take investment in manpower and technology to operate and enforce a shot clock on every player in a tournament, but that’s where all the investment in PGA Tour Enterprises can be wisely utilized to help build a better and more marketable product. In order for habits to meaningfully change across the game, it has to work from the top down as aspiring pros see what’s expected of them when they reach the tour and prepare accordingly.

By the 1950s, major league leaders were content leaving it up to the players themselves to quicken the pace. Sound familiar? “Who is going to make a pitcher hurry up when that is his bread and butter?” said National League chief and future baseball commissioner Ford Frick, echoing a long-standing narrative in professional golf.

“Look, if you could somehow implement the shot clock in some way and be able to police it consistently, I think that would be a really cool thing,” Rory McIlroy said last week after his TGL event. “Much easier to do in this controlled environment compared to a golf course that spans 100 or 200 acres.”

But the Euro circuit went all in with a full-fledged 72-hole experiment in 2018, staging the annual Austrian Open as an event called the Shot Clock Masters at Diamond Country Club in Atzenbrugg, Austria.

And both similarly dragged their feet at doing anything about it, with successive PGA Tour commissioners content with play simply finishing by the end of the designated broadcast window no matter how early the leaders needed to start to get that done. But golf – from the fans to players to tour administration – now seems ready to finally tackle the pace-of-play challenge.

In 1996, the rulemakers tackled the growing concern about slow play by authorizing committees to establish pace-of-play guidelines and enforce them by applying penalty strokes for unreasonable delay.

“It was much faster than I thought, but … I felt like I had time to choose my shot,” said Fowler’s TGL teammate Matthew Fitzpatrick. “I just wish that was real golf, as well.”

“Within an inning, we all kind of looked at each other and said we’d seen enough … we need this in the big leagues,” Morgan Sword, MLB’s executive vice president of baseball operations, told the Wall Street Journal of his executive group’s reaction to watching their first Class A game with a pitch clock.

“Within an inning, we all kind of looked at each other and said we’d seen enough … we need this in the big leagues,” Morgan Sword, MLB’s executive vice president of baseball operations, told the Wall Street Journal of his executive group’s reaction to watching their first Class A game with a pitch clock.

How baseball went about implementing a pitch clock to wide acclaim is a lesson that golf’s leadership can learn from. And even though golf would require monitoring dozens of players simultaneously over hundreds of acres on a course instead of two players in a fixed spot separated by the 60 feet, 6 inches between the pitching mound and home plate, it is not an impossible challenge to consider.

This week’s “In Case You Missed It” is part of a multi-story “Change of Pace” package that first appeared in Monday’s issue of Global Golf Post examining pace of play in golf. For a link to the Monday issue, which contains the stories, click HERE.

The time limits were enforced by rules officials riding with each group in carts with large digital clocks displaying the player’s name and remaining time.

Baseball and golf have more in common beyond being stick-and-ball games. Neither measure how long it takes to complete their competitions in units of time, but instead with innings and holes. Both endured issues with the expanding duration of how long it takes to reasonably finish, which deteriorated the experience of the players as well as fans.

It only took Major League Baseball 122 years to finally enforce that rule with the implementation of a pitch clock in 2023.

“Within an inning, we all kind of looked at each other and said we’d seen enough … we need this in the big leagues.” – Morgan Sword

How can golf do that? For a blueprint, look to baseball.

But penalties for slow play are rarely (or inconsistently) assessed in golf even as tournament rounds on tough courses in difficult conditions have pushed six hours. The worst slow-play offenders have learned how to game the system and pick up the pace just enough when they’re put “on the clock” to avoid penalty. The only way to stop that gaming is by having a real shot clock with real consequences.

The only thing agreed upon was that the original 20-second pitch rule was feckless.

“The rule cannot be commended too highly, but unless there is to be an official timekeeper … it is difficult to see how the 20 seconds can be determined accurately,” read a newspaper story on Feb. 28, 1901.

- Players had 40 seconds to hit their shot (the first player to hit approach, chip or putt in each group was allotted an extra 10 seconds);

- Failure to hit a shot within the time limit incurred a one-stroke penalty;

- Players were allowed two time extensions (40-second timeouts) per round.

By the end of 2023, the average time of a nine-inning MLB game had clocked in at just under 2 hours, 40 minutes – 23 minutes shorter than in 2022 without a pitch clock and marking the league’s fastest average regulation time since 1985. Attendance across the league improved as well.

• • •

“Loving this shot clock deal on the European tour,” Horschel wrote on Twitter. “Amazing how fast rounds go when players play within the rules. And guys are still playing great golf. Shocking! Wish we had something like this on the PGA Tour.”

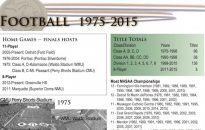

The results seemed transformational. The stated goal of then-European Tour CEO Keith Pelley was to try to reduce the average time of rounds by 45 minutes. It came close. The first round’s average time fell 34 minutes from the previous year’s Austrian Open – from 4 hours, 47 minutes to 4:13. First-round scoring averages dropped as well by more than half a stroke and no players were penalized for a shot-clock violation.

Through the ensuing years, baseball kicked about experiments like third-base umpires carrying stopwatches and stadiums installing countdown clocks with horns on scoreboards, but the efforts proved typically unreliable and weren’t enforced consistently.

In 1901 – the year Teddy Roosevelt became U.S. president after William McKinley was assassinated and radio signals first reached across the Atlantic Ocean – both the National and American leagues in baseball codified a specific time limit in their rule books on how long it should take a pitcher to put the ball in play.