PULLMAN — Tim Brandle couldn’t believe his iPhone wasn’t buzzing a hole in his pocket. It was a sunny Saturday afternoon earlier this month, and he was sitting at his 8-year-old daughter’s soccer game, keeping one eye on the score of the Washington State football game.

The Cougars were getting pummeled in an eventual 59-10 loss to North Texas, which handed WSU its worst setback in more than a decade. Brandle is a WSU alum, so as a fan, he felt disappointed. But as the treasurer of the Cougar Collective, the main NIL arm for WSU’s athletics programs, he felt something even more important: concern.

In recent years, after the Cougars dropped similarly discouraging games like these, Brandle’s phone would light up with the worst kinds of notifications: Members of the 1890 Club, fans who committed to a monthly donation of $18.90 to support NIL at WSU, canceled their memberships out of frustration. They would do so during the game, or sometimes at the end.

So sitting at this soccer game on Saturday, Brandle was expecting several notifications alerting him that WSU fans were pulling their donations and uprooting critical momentum for the group, a key player for an athletics program already swimming upstream. If fans yanked their donations after WSU’s close losses to New Mexico and Wyoming last season, how many more would do so after this collapse?

As the game unfolded and the Cougars were getting blown out, Brandle hadn’t received a single email of the sort. He figured something was wrong on his end. He felt confused.

“I did check the settings on my phone to see if my Gmail was disconnected for some reason,” Brandle said.

Turns out, Brandle’s phone was in perfect condition. By the time the clock ran out on WSU’s loss, only one 1890 member had canceled their membership. Because of past patterns, Brandle was expecting more. Instead, the collective added more memberships that day — some even during the game itself.

As the days went by, Brandle began to understand the trend beginning to emerge: WSU fans were understanding the importance of NIL donations. Not just after huge wins, but also after bitter losses.

“The mindset of Cougar fans is starting to tilt. It’s starting to change,” Brandle said. “I think folks are realizing that the Cougar Collective is just this scrappy bunch of volunteers who are trying to give them everything they possibly could want: a wine, a beer, a cocktail, a coffee. We’re trying to give them things. We’re trying to give them all these different opportunities to help fund this fund that’s desperately needed. We’re not the problem. We’re the solution. And folks are finally starting to be like, oh, yeah.”

In this new era, Washington State needs NIL boosts more than ever. The Cougars have a home in the rebuilt Pac-12, which launches next year, but they’ve lost a lot along the way. They no longer receive funding from the traditional Pac-12, which handed each member school roughly $20 million annually, and athletics programs no longer have access to the recruiting advantages they enjoyed as a Power Five operation.

At WSU, that has spawned all manner of problems. In March 2024, when men’s basketball coach Kyle Smith left for the same job at Stanford, he said he might have thought twice about leaving had the conference stayed intact. Jake Dickert, who coached the football team from 2021-2024, put on a brave face for the Cougars — but even he often lamented the position his team found itself in, left behind by former conference allies.

But since then, some of the biggest issues facing WSU have involved the school’s NIL resources, or lack thereof. Last winter, the Cougar Collective put together a package of more than $1M in NIL to try and retain star quarterback John Mateer, a meaningful accomplishment for the organization, a sign that members could rally at the right time. But Mateer entered the transfer portal and took his talents to Oklahoma, where he accepted a package of around $2.5-$3M in NIL, according to several reports.

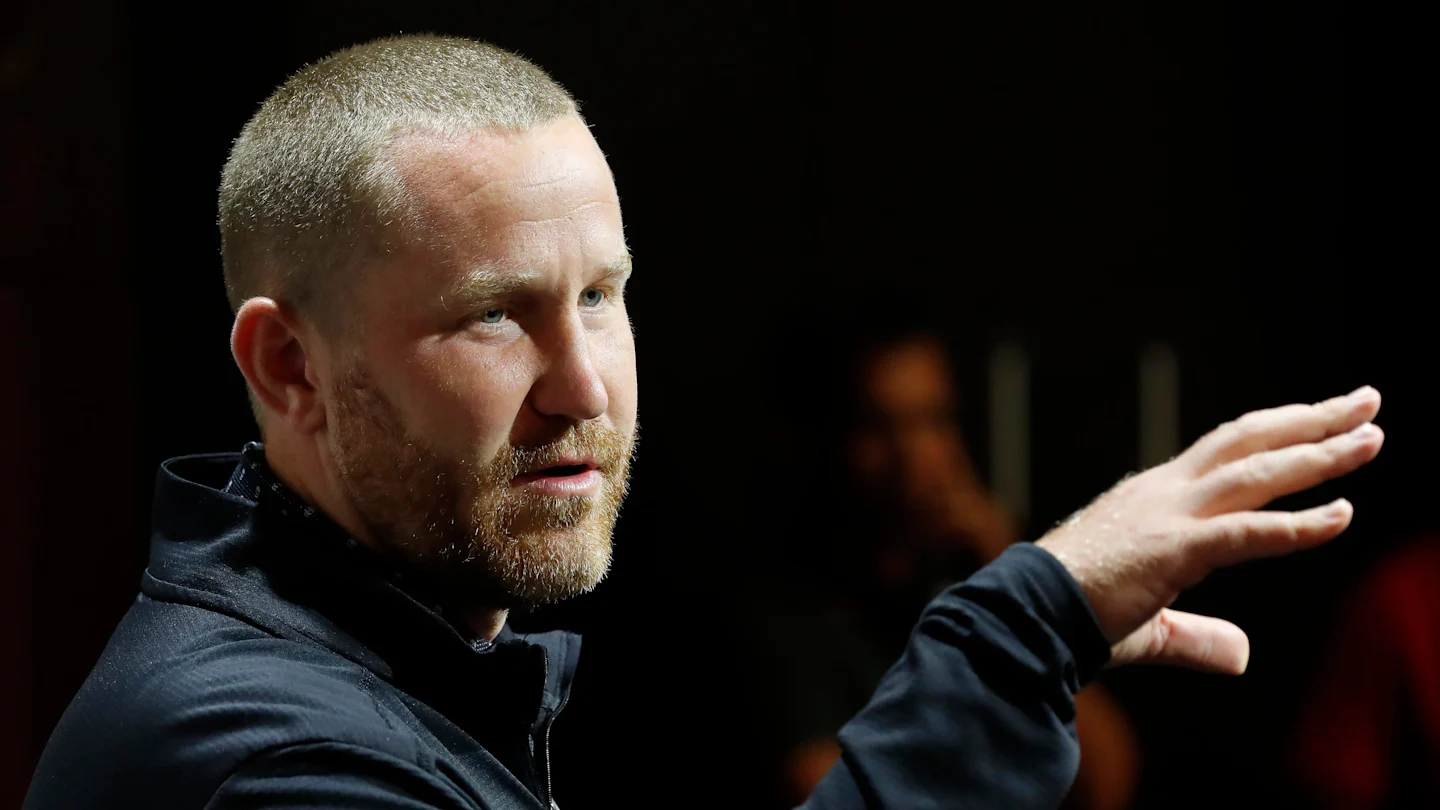

A few weeks later, Dickert left for Wake Forest and WSU hired coach Jimmy Rogers, who spent two years in the same role at South Dakota State. This fall, his Cougars have started 2-2. After their last loss, a 59-24 setback to archrival Washington in the Apple Cup last weekend, Rogers made headlines with one postgame quote.

“We don’t have the resources naturally to compete with $30 million and a roster that’s loaded,” Rogers said, referring to the Huskies’ advantages in recruiting and NIL funds.

Two days later, Rogers walked those comments back, saying he had never been one to complain and doing so wouldn’t get the Cougars anywhere. Maybe he had a point in his apology, but he also did in his first statement. It is true that Washington has access to tens of millions more NIL dollars than WSU, both in institutional dollars and alumni donations, which surely played a part in the Huskies’ win over the Cougars.

It’s also worth examining how WSU landed on Rogers as head coach. The Cougars are paying Rogers a five-year contract worth about $1.57 million annually, according to reports, which is $1M less than what Dickert earned in 2024. In the new Pac-12, Rogers’ annual salary appears to rank sixth of seven football coaches, ahead of only Fresno State’s Matt Entz.

But WSU gave Rogers $4.5 million to spend on an assistant coach salary pool, WSU athletics director Anne McCoy said earlier this year, which is $1M more than what brass had planned for Dickert before he departed.

In any case, WSU did well to stay within striking distance in the Apple Cup. In his first start of the season, quarterback Zevi Eckhaus totaled three touchdowns and helped the Cougars stay within one or two scores for about three quarters. The Huskies won the fourth, 28-0, in some ways a reflection of the state of both programs: A Big Ten member flush with NIL cash, UW could afford to build the depth over the offseason to pull away in the fourth quarter. A Pac-12 holdover with fewer resources, WSU could not.

Another illustration of how Washington won Saturday’s game: Over the offseason, when former WSU linebacker Buddah Al-Uqdah hit the transfer portal, he accepted a lucrative NIL offer and transferred to UW. He left the game early with an injury, but before then, he totaled four tackles, including 1/2 for loss.

“If you don’t want your rival to take advantage of you developing a player for three years,” Brandle said, “then we gotta step up, you know?”

In the last two football seasons, WSU has become well-acquainted with that reality. After the 2023 season, QB Cam Ward transferred to Miami, where he went on to win the Heisman Trophy and become the No. 1 overall selection in this spring’s NFL draft. Last winter, the Cougars lost Mateer, who was tied for the nation’s best odds to win the Heisman before suffering a hand injury last weekend.

In the WSU NIL orbit, those kinds of brutal departures have prompted some fans to rethink their approaches: Why donate when our quarterback is getting millions of dollars more to transfer elsewhere? Why donate when our team can’t beat Wyoming at home?

But the way Brandle sees it, the tide is turning. The development that helped turn things around: In 2024, the NCAA passed a new rule that allowed athletes to pursue NIL opportunities with little oversight. That allowed coaches and administrators to mention their schools’ NIL collectives in public, in front of cameras, in front of fans. No longer did the collective have to operate in the shadows, walking on eggshells to avoid breaking rules.

Last fall, Dickert began wearing hoodies with the Cougar Collective logo to news conferences and other events. Now Rogers and other WSU coaches do the same. Cougar assistant coaches wear shirts with the logo. They keep hats adorned with collective logos in their offices. That kind of visibility has made its way to Washington State fans, who can now buy collective merch: Shirts, hats, beer, cocktails, wine, coffee, you name it. It’s also helped the organization raise even more money, which it passes on to student-athletes in the form of NIL.

In truth, it’s made life easier on Brandle and the other board members at the Cougar Collective. In its infancy, even as recently as two years ago, the collective had to fight for credibility. Because the importance of NIL was still setting in around the country, it was doing the same to WSU donors, who preferred to give to the Cougar Athletic Fund, which finances things like scholarships, coaches’ salaries and facilities.

Brandle and other members had to strike a delicate balance: They had to emphasize to donors that their gifts to the CAF were invaluable, that they should continue to give. But they also had to educate them on the importance of their organization, which might have a more immediate impact on game results — but because of NCAA rules, coaches weren’t allowed to endorse it in public. As a result, donors felt pulled in several directions, confused about where their money should go.

“Whenever there’s donor confusion, obviously, you just get no donations,” Brandle said. “Donors are paralyzed if they’re not entirely sure what to do.”

Those days are in the past, Brandle said. He described the Cougar Collective, CAF and WSU athletic department as “aligned for the first time in a couple years.” This summer, McCoy said “we interact with them on a regular basis.” It’s clear that after an early period of mixed messages, brass at WSU and the Cougar Collective have come together and made things easier to understand for donors, who have responded in kind.

“The Cougar Collective, they’ve been amazing partners, and they continue to be amazing partners,” McCoy said. “I think that as we’ve been able to work more closely with them over the past year-plus, we’ll say, I think we’ve continued to brainstorm — all of us, the Cougar Collective and folks here at Washington State — on ways we can lean into our unique abilities and the things that we can each do.”

How much NIL is WSU working with? The numbers are a bit tricky to wrangle, a purposeful effort from McCoy and other school brass to maintain competitive advantages and prevent other schools from prying away Cougar athletes with lucrative NIL offers. At the beginning of the year, as schools across the country braced for the passage of House vs. NCAA and prepared to directly compensate athletes, McCoy said the WSU football team’s annual NIL pool would be $4.5 million.

That is a fraction of the maximum of $20.5, which only the deepest-pocketed schools are spending. But additionally, McCoy indicated that part of the $4.5 million goes to scholarships and stipends, making the true NIL figure lower. It’s unclear what it is. But because the Cougar Collective remains in operation, it can sprinkle additional NIL funds on top of athletes’ compensation from the university.

The organization has the funds to do so because of the memberships it keeps adding. The collective has about 2,100 active 1890 Club members, Brandle said. Do the math and that comes out to about $475,000 annually. The goal the collective is shooting for: 5,000 members, which would net around $1.2 million per year from those donations alone, which doesn’t account for additional funds from the Ol’ Crimson beer, cocktails and merch.

Is that goal feasible? According to the WSU Alumni Association, there are about 250,000 living WSU alumni.

“And there’s only 2,150 1890 Club members,” Brandle said. “Give you 10% of that, and we have enough resources to compete with any team in the country.”

In that way, officials like Brandle, WSU legend and collective board member Jack Thompson and others are still campaigning for more support from Cougar alumni. Trying to raise more awareness, trying to instill the importance of NIL to those who remain unaware — or who aren’t ready to commit.

They haven’t reached every goal they’ve set, Brandle acknowledged, but they feel palpable momentum. They’re continuing to push the charm of small-town Pullman, the sense of community athletes feel here. Can their NIL collective help keep WSU athletics competitive in the years ahead, help retain athletes who play well and fetch offers from other schools? So far, Brandle hasn’t gotten any iPhone notifications to the contrary.