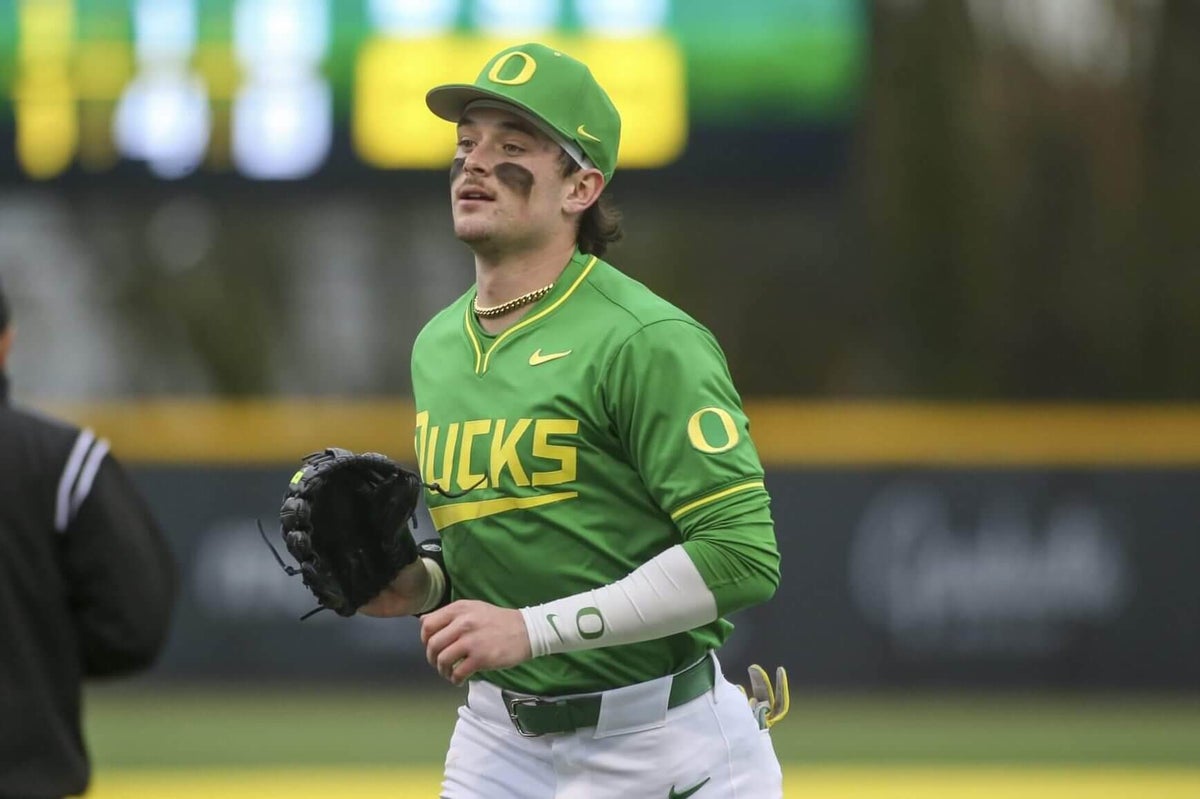

EUGENE, Ore. — Mason Neville wasn’t sure what to expect when he entered the transfer portal in the summer of 2023.

Thousands of athletes have gone to the portal after stellar individual seasons in search of more NIL money, higher-profile programs and the chance to chase trophies.

Neville wasn’t in that group, and he knew it. As a freshman outfielder at Arkansas in 2023, the Las Vegas native struck out 20 times in 33 plate appearances. Never mind that he was a top-100 national prospect coming out of high school and was selected by the Cincinnati Reds in the 18th round of the 2022 MLB Draft.

One year of college baseball and Neville had, in his own words, no leverage.

“There were jumps I needed to make as a baseball player, and I knew that,” he said. “But when you’re not getting playing time, it makes you second-guess what you’ve done previously. I was asking myself, ‘Am I not good?’”

Two years and 2,000 miles later, the answer to that question has become clear.

Neville is thriving in his second season at Oregon, hitting .293 with a 1.179 OPS and leading the country in home runs with 26. He’s the centerpiece of an Oregon offense that has the Ducks positioned to make a run at their first College World Series appearance in school history. Oregon, the No. 12 seed in the NCAA Tournament, plays Utah Valley on Friday at 6 p.m. (PT) in the first game of the Eugene Regional.

Neville is No. 26 in MLB.com’s latest mock draft and No. 38 at Baseball America.

But more than confidence and an impressive stat line, Neville has something else that had gone missing in Fayetteville: Joy.

That much is evident in the fun he has when little kids from the community crowd around him after games, begging for autographs and selfies. It’s clear from the smile that creeps up whenever he blasts a shot over the fence and trots around the bases, a joy he can’t fully describe because, “I kinda blackout after home runs,” he said.

Neville can barely talk about success — his and his team’s — without breaking into a grin and marveling at how much better things are not just for him, but for them. Joy has become the foundation of this season, allowing him to take constructive criticism from his dad, a former college player, and his coaches, without it shaking his confidence. He’s remembered not only that he’s good at this game, but he loves it, too.

And those things are true even when he’s not playing it perfectly.

When he watches film of his freshman year, Neville sees a kid desperate to prove himself, who thought the only way to do that was to bomb baseballs over the fence. He was in his own head too much.

That was obvious to Mason’s dad, Trevor, a former junior college player who first put a bat in Mason’s hands, helped him become one of the best players in the country and then watched his confidence crumble at Arkansas.

“If his confidence wasn’t completely broken, it was cracking,” Trevor said. “For athletes, that fear of failure is always there. It was tough. He was saying, ‘Does anyone even want me?’ I tried to remind him, ‘You’re a great ball player, and people recruited you for a reason. You are going to have options.’”

Dad was right. Numerous schools reached out to Mason once they knew he wanted to transfer, with Oregon coach Mark Wasikowski one of the first to call. Trevor said the day after Wasikowski talked to Mason on the phone, the sixth-year coach was in the Nevilles’ Las Vegas living room, telling Mason, “We lost you once, we’re not gonna lose you again.”

Mason, a desert kid who loves sunshine and being outdoors, had concerns about playing in a cold, rainy climate where early-season games are often rescheduled because of downpours. But he also figured if he was successful in Eugene, he could be successful anywhere.

“I’ve grown to appreciate it a little bit. Those four-hour practices in the rain, it builds character,” he joked.

He’s excelled at Oregon partially because he’s taken pressure off himself. Ducks hitting coach Jack Marder has stressed that hitting home runs is not the goal — getting on base is. He’s harped to the entire team to cut down on strikeouts. In 2024, the Ducks totaled 531 strikeouts in 60 games; through 56 games this season, they’ve struck out just 407 times. He’s told players that being good offensively is not only about how you’re hitting the ball but “how you’re setting the table to create runs for other players.”

Neville, Marder said, didn’t necessarily need major mechanical changes. He just needed a different approach.

“He was a completely out-of-sync mover at Arkansas,” Marder said. “His lower half and upper half didn’t work together, which meant he had to be perfectly on time (to get a hit). That can really put negative thoughts in a player’s head if they have to be perfect to be successful.”

More reps have helped, too. After battling an injury at the beginning of 2024, Neville settled into the Ducks’ lineup late last season, starting Oregon’s final 23 games and batting .318 (28-for-88) with 10 home runs in that stretch. He credits his success to the simplicity of routine.

Neville’s also come around to understanding the value of getting on base no matter how it happens. He set the single-season program record for walks in the finale of the Washington series and has walked 52 times in 53 games, tied for the 14th most in Division I.

“Being more disciplined at the plate is a big part of my success this season, and knowing when I get my pitch, I’m not missing it,” Neville said.

Nothing beats the feeling he gets in the split second just before his bat connects with the ball.

“When you’re on time and you get a pitch you can handle — you can usually tell based on how it comes out of a pitcher’s hand, it looks a little different — when you know it’s in your zone because you’ve done it over 1,000 times in BP, you know you’re about to smash it.”

Mason’s season has been especially gratifying for Trevor to watch, even if he still occasionally gives feedback to his kid.

When he strikes out, Mason might try to justify it to Trevor, telling Dad that in the big leagues, an ump would have never called that particular pitch a strike. Trevor won’t have it. “If the ump calls it a strike, it’s a strike! You gotta swing at it!”

It reminds them both of shouting matches they’d get into when Mason was younger and Trevor would throw batting practice. If a pitch sailed by and Mason didn’t swing, Trevor would call it a strike, igniting an argument. Mason would claim the pitch was way out of the zone, while Trevor, incredulous, would tell his oldest, “You do not argue with the person throwing BP!”

They laugh about it now. Mason described Trevor as “my best friend,” the person who instilled confidence in him even as he struggled early in his college career. Trevor and his wife, Jessica, have made it to almost every single Oregon weekend series this season. Mason grudgingly admits that his dad has “been right about pretty much everything.” When he’s home in Vegas, he asks daily if they can go hit. When they’re not in the cages, they’re usually on the pickleball court or maybe the golf course. Mason and his younger sister Emma, a freshman beach volleyball player at Cal State Bakersfield, will team up against their mom and dad to play anything for hours.

“We lose every time,” Mason groaned. “They smash us no matter what we’re playing. They always find a way to beat us. It kills me.”

Some parents see value in letting their kids win to boost their confidence. Trevor doesn’t believe in that. Asked who the best pure athlete in the family is, he initially said if the Nevilles held some sort of sports decathlon, where they had to demonstrate skill from each of the major sports, “I’d smoke ’em.”

Later, he recalibrated. His kids are Division I athletes, a level he never reached. He should probably be realistic.

But Mason loves the trash talk. Over the last few years, he has had three major goals:

1) Find joy in baseball again, 2) Help his team to Omaha, 3) Beat his dad in pickleball.

He’s one-for-three. He knows that in baseball, batting .333 is pretty good. But he’s not satisfied yet.

(Photo courtesy of Oregon Athletics)

th blast

th blast

Pitching reinforcements

Pitching reinforcements Bowie behind the plate

Bowie behind the plate

(@bigorangetony)

(@bigorangetony)