“A real-life Ted Lasso.”

That’s the best way Andrew Brewer can put Gardiner MacDougall.

He’s a coach. He has the moustache. Even at 65, he has the infectious, undying energy. He can talk to, motivate and connect with people. He’s the ultimate recruiter. He can make anybody feel good about themselves. He’s humble.

Like Lasso, he always has a joke lined up for a news conference. He’ll tell you about the two ladies in his team’s life, Lady Luck and Lady Mo’, and that you need to find Lady Luck before you find Lady Mo’ in the crowd. He shows up early at the rink every day to find them, he says.

He signs his texts with “GMac @ Mct” (short for Moncton) and starts or ends every conversation with a stranger with a genuine interest in what they do, where they’re from and who their family is.

According to those who’ve worked with him, he knows what his strengths and weaknesses are, doesn’t try to be the X’s and O’s guy and surrounds himself with people who do what he doesn’t.

“I have my efficiency chart. It’s 30 years old, way before analytics,” he said on a recent phone call, chuckling, not because he has any disdain for analytics but because he has aged himself again.

“My coaches do more video than I do.”

But there’s one thing MacDougall has on Lasso.

“He has had way more success,” Brewer said. “He’s better at winning.”

Winning seems to be all he does.

He became the winningest coach in Canadian university hockey history at the University of New Brunswick, where he captured nine national titles. Last year, in his final one at the helm of the UNB Varsity Red, he went 43-0. He then guided Canada to a perfect record at the U18 worlds, winning gold in a come-from-behind win against the USA. In 2022, when the Memorial Cup-host Saint John Sea Dogs fired their coach following a shocking first-round exit in the QMJHL playoffs, they asked MacDougall to fill in. He took over a team he’d never seen play and, in 39 days, turned them into Memorial Cup champs.

Brewer says the question was always, “Is the schtick going to work in junior?”

This year, MacDougall answered it, leaving his beloved Reds after 24 years to take over as head coach of the QMJHL’s Moncton Wildcats.

In his first season behind the bench, they won the QMJHL title, going 16-3 in the playoffs. On Friday, at the 2025 CHL Awards, he was named coach of the year.

This season, with another championship and another coaching award, was different, though: his son, Taylor, an up-and-coming mind in the game, was also the team’s general manager.

The combination?

“It has proven to be pretty powerful,” Brewer said.

Gardiner MacDougall is in a Tim Hortons drive-thru.

“Small iced cappuccino with chocolate milk and that’ll be all, thank you very much,” he says out of his car window.

He’s on his way home from another day at a hockey arena. It’s the week between the end of the regular season and his team’s four-round QMJHL playoff run. He’s going to win it, but he doesn’t know that yet.

He’s incapable of looking that far ahead. Gardiner is all about micro vision, his idea that if you have enough positive micro days that the macro takes care of itself.

But he can begin to reminisce on the late-career move he made from Fredericton and UNB to Moncton and the Wildcats.

UNB, Gardiner said, was his NHL when he got the job, and it stayed that way “’til the end” for him.

But his journey in Moncton “has been invigorating.”

It started with a call from Robert Irving, the team’s billionaire owner of New Brunswick’s Irving family, who owns Irving Oil, potato giant Cavendish Farms (of which Robert is the president) and the lumber business J.D. Irving (of which he’s the co-CEO).

Irving had known Gardiner for years, and after deciding not to renew the contract of his head coach, he reached out.

After an initial visit to the facilities to meet with Irving, Gardiner’s decision was on hold because he had to go to Finland for the U18s.

Irving was willing to wait.

“He’s a winner and his energy is second to none,” Irving said. “It just says that we’ve got a winner, someone who knows the game very well and knows how to bring players along, and develop them, and coach them to be successful on the ice and off the ice. And he just brings an exuberance to everything that he does and everyone around him that we’re here to win, and Gardiner’s going to be the man to do it.”

Gardiner eventually told him that if he took it, he’d want to be in charge of personnel and to have people he knew be a part of it.

He wasn’t thinking of his son when he said that, though. After calling Taylor on his way home to Fredericton and telling him that he’d have to look for a general manager because he didn’t want to play that role at this stage in his career, Taylor said, “Well, Dad, I’d be interested in that.”

At the time, Gardiner thought it was intriguing and told Taylor, “OK, well I’ll let Mr. Irving know and you can go meet him and see where it goes,” knowing that the general manager would actually have more day-to-day dealings with Irving than him.

Taylor, 35, was working for Roy Sports Group (RSG). He was the agency’s legal counsel, handled all of the legal on their marketing side, did NHL contract research and preparation, recruited and scouted for them in the Maritimes and Quebec and was starting to negotiate deals. Allain Roy, the president and CEO of RSG, was grooming him to be one of the people to take over the agency at some point. “And he wasn’t very far from there,” Roy said.

Before being hired at RSG, he earned his Juris Doctor from UNB, his MBA from the Edinburgh School of Business, and played for five years in the QMJHL, five more years under his dad with the Reds, and briefly professionally in the ECHL with the Brampton Beast and EIHL with the Edinburgh Capitals.

Irving was immediately “attracted to the father-and-son tandem approach, knowing that they’ll be able to work very closely together and trust each other.”

After interviewing with Irving, Taylor was named the team’s general manager and director of hockey operations.

Taylor just hoped he could “be more useful to (Gardiner) as a GM than I was as a player.”

“That would be nice,” Taylor said, “and not a high bar.”

As a player, Gardiner said Taylor “totally bought in,” was a “terrific leader” and “played his role” on strong teams where he was often fighting for his spot.

As a manager, Taylor believes junior hockey’s “a beast of its own.” In pro, he says you can build around a particular vision for what a team should look like. In junior, you have to be more flexible.

From his dad, Taylor also knows how hard he works to build relationships with everyone in an organization, from players to rink staff.

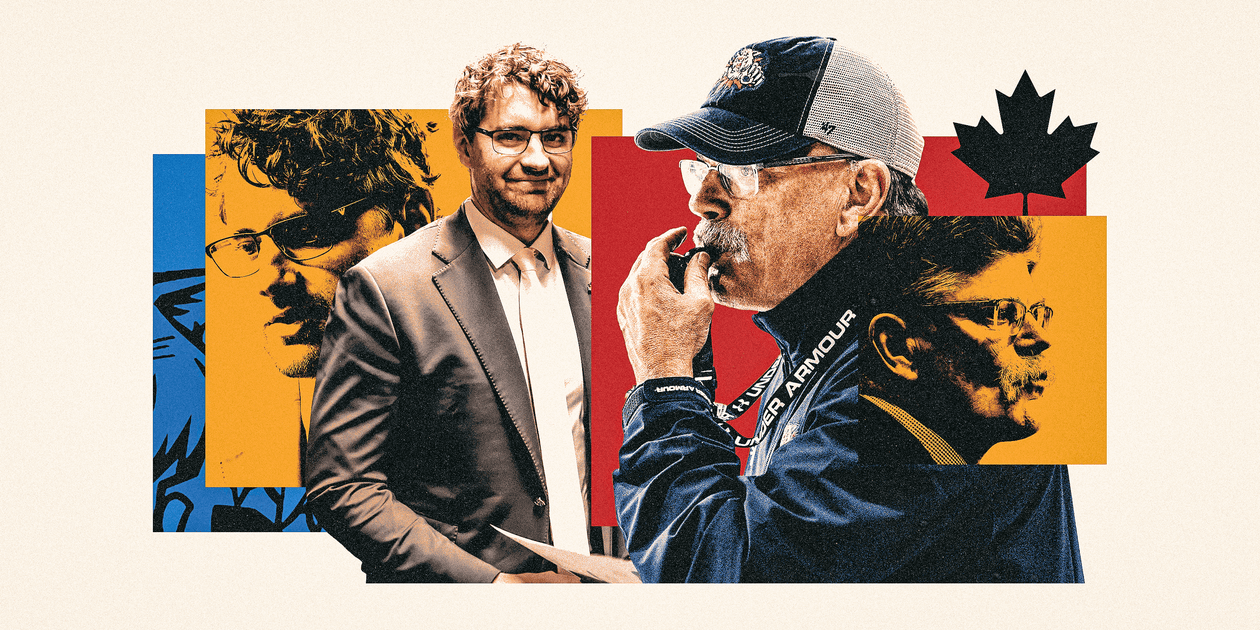

Taylor and Gardiner MacDougall. (Daniel St. Louis / CHL)

Gardiner and Taylor both say they’ve found a yin and yang to their working relationship in the different strengths and experiences they have.

Gardiner grew up with three younger sisters in a Prince Edward Island community of a couple of hundred people called Bedeque. He started working on the farm and at the local hardware store at 12 and says his persistence, habits and love of community come from his old man.

His passion for coaching started with a passion for teaching as a physical educator in Norway House, Manitoba, more than 800 kilometers north of Winnipeg. He had a poster of Terry Fox, one of his heroes, in his office. “Enthusiasm is contagious, catch the fever,” it read.

“You always want to be enthusiastic,” he says. “I’ve always had energy, and you channel that.”

Gardiner says that goaltending (Kings prospect Carter George) and “a guy from the Yukon” (2026 NHL Draft sensation Gavin McKenna) won him gold at U18s, and William “Willie” Dufour won him that Memorial Cup in Saint John. He’d rather talk about being a product of the mentors he’s had (Clare Drake, Andy Murray, Dave King), the books he’s read and the people and places he comes from, than himself.

Taylor brought contacts with players, agents, scouts and executives from across the NHL and QMJHL. He knew the league and his contacts with prep schools and colleges across the United States had positioned them well for the NCAA’s opening of eligibility to QMJHL players. Through his time as an agent, he understands now just what players want, but what parents do.

When Taylor was playing junior, Gardiner joked that he was his best recruiter. Once, when Taylor was 16, he recruited a 20-year-old for his dad, who went on to become an All-Canadian, asking Gardiner to give him the phone during a recruitment call.

“He has done an amazing job,” Gardiner said. “You get a lot of opportunities through the years of going to pro, or major junior, or Europe, and at UNB I was the coach, I was the GM (and) you can look in the mirror and if you’re not doing well the coach can say to the GM ‘Get me better players’ and the GM can say ‘Coach, coach better’ and I had those discussions with the mirror for 24 years. So, to have Taylor, I can see the significance of him and the cohesion between your head coach and your general manager is so essential.”

Gardiner also said his son’s communication skills are “top notch.”

“People say simplicity is the ultimate source of sophistication, and I think he has just a great way — and part of it is working with the law — of getting to the facts,” Gardiner said.

Roy is in his 25th season in the agency business and has known Taylor since he was 12 years old because he used to run summer camps for prospects out of UNB. Taylor later became a client and lived with Marc Lavigne, one of Roy’s agents, in the Montreal area.

He called Taylor closer to family than a former employee. He describes Gardiner as “a guy with a lot of panache.”

After taking the job with Moncton, Gardiner gave Roy the hard MacDougall pitch for one of his clients earlier this year.

“He was like ‘You know what, Al, there was a kid once and I went to see him six times and you know what happened on the seventh time that I went to see him?’ And I was like ‘Let me guess, Gardiner, you got him to go to UNB?’ And he was like ‘Yep. I’m not going to give up,’” Roy remembered, laughing. “He just lets you know that he’s just going to keep coming at you, and I respect it.”

Meanwhile, Taylor was described as “very smart” and “a little bit more softly spoken.”

“I think (Taylor) will rise through the ranks of pro hockey very quickly,” Roy said. “I think there’s a bit of a misconception in the pro sports world that you can’t be a good person and be a good manager, and I think he’s that guy that will help break that trend. He puts the individual first, but he’s not afraid to make tough decisions, not afraid to have tough conversations.”

In that way, Taylor reminds him of Hockey Hall of Famer Cliff Fletcher, who famously never had a negative conversation with someone (whether firing, trading or releasing someone) unless he could have it in person.

“That has always stuck with me because I’m like ‘man, do I see the opposite a lot in this world now — people just afraid to communicate because of what’s going to come afterwards (which is more communication),’” Roy said. “Taylor’s a great communicator, I think he thinks the game very well, he uses advanced stats but does not hide behind them.”

When Taylor first told Roy about the job, though, Roy had an honest conversation with him.

“How’s it going to be with your dad?” he asked. He knew that Irving was “a pretty intense individual,” too. But he also knew that Taylor would navigate it all. And after continuing to work with him in a different way this year because he has “quite a few kids” on the Wildcats, Roy has seen both of them do just that.

“It’s a hell of a start,” Roy said. “If their record was reversed, maybe it would be a different conversation.”

Father and son are both thankful for what this last year has given them.

“We’re wildly fortunate to have this opportunity. It has been a privilege,” Taylor said. “There have been plenty of ups and downs, and there will be many more, but the one thing with him leading the charge is that there’s always a lot of buy-in, and it starts with his passion and enthusiasm for the process.”

Added Gardiner of working with his son, for a rare moment losing the words that have always come so freely: “It’s been tremendous.”

In the Memorial Cup’s tournament-opening news conference, Gardiner sat at the podium, cracked his jokes, and said, “If you’d told me 13 months ago that this may be happening with your son, I don’t know if even Hollywood could write that script.”

A few short days later, as he took the podium following a 3-1 loss to the Medicine Hat Tigers, Gardiner didn’t have a joke to tell.

Instead, he said that about 20 minutes prior to puck drop, Taylor had gotten a call from the RCMP telling him that Pat Buckley, his father-in-law, had been golfing in Rimouski after driving up to the Memorial Cup from Fredericton that day, and had died from a heart attack.

“It’s certainly a devastating loss. It’s the hardest game I’ve ever had to coach,” Gardiner said, catching his breath. “Pat Buckley was an unbelievable sportsman, a top-notch golfer, a former university hockey player. He was a second father to my son. They bonded like no other.”

In a moment of loss and grief, Gardiner was there for his son. All year, he’d asked his players to embrace one of his many mantras: F.O.E. (Family Over Everything). Now he was practicing what he’d preached, his humanity on full display.

Everyone who knows him has a story about that humanity, because he has made so many feel like family along the way.

The way Brewer’s goes, he was a university student at UNB who’d done a marketing project about how the Reds could sell more tickets. As part of the project, he’d made a commemorative video of the national championship they’d just won in 2007. His girlfriend at the time, now his wife, was working for the athletic department and showed the video to her boss, who showed it to Gardiner, who asked if he could play it at their ring ceremony.

Time passed, Brewer graduated and took a job in government when another call came from Gardiner. He asked him if he could make another video for the start of their new season and told him that he wanted to start using this new video program called Stiva that some NHL clubs were using, but didn’t know how, and wondered if he’d be interested in helping with it.

Brewer said yes and became his video coach. Seven years after Gardiner gave him his first job in hockey, Brewer was an assistant coach with the Toronto Maple Leafs. In between, Gardiner helped him get his first video coaching job with Hockey Canada. Last summer, when he brought the U18 trophy home to Fredericton, Gardiner invited Brewer to the house to celebrate.

Brewer isn’t the only one with a story like that, either. Lucas Madill and Ryan Hamilton, two sports psychiatrists who work with Hockey Canada now, were disciples of Gardiner’s.

“I mean, I was a university student coming in and getting involved with a past national champion and big program and he made me feel welcome, he gave me a voice, he gave me an opportunity to be a part of the program, and then gave me more and more opportunity,” Brewer said.

Sea Dogs president Trevor Georgie has his own stories from the 39 days he spent with Gardiner en route to their Memorial Cup together. Like Brewer, he’ll tell you of the immediate bond he formed with Travis Crickard, who was an assistant coach on that team and is now their head coach and general manager, and how Gardiner helped Crickard land his first Hockey Canada job as an assistant on his staff at U18s.

He’ll also tell you how “devastated” his team was when they lost in the first round that year, and how one by one, Gardiner turned each player’s psyche around and got them to believe again.

Before naming Gardiner interim head coach for that Memorial Cup, Georgie interviewed multiple coaches. Gardiner was the only one without NHL experience. But Gardiner “was really special.”

Waiting to hear back, Gardiner texted Georgie, “It’s a great day to be a Sea Dog.”

On their first walk through the dressing room, Gardiner talked to himself and said something along the lines of “I think I can capture their hearts in here.”

His first day on the job, Georgie remembers the office was still waking up, with everyone grabbing teas and coffees, and “Gardiner had already done like 10 kilometers and a million pushups and it was like ‘OK!’”

“He genuinely has that seize the day personality. That’s just his way,” Georgie said. “He is not letting a day go by. He is enjoying every minute. It’s from the second he wakes up. It’s really, really incredible.”

Though they’re now rivals within the league, Georgie and Taylor are also close friends. Several of Taylor’s clients at RSG were on that Sea Dogs team. They know each other’s families and are both young fathers (Taylor has two kids, 4 and almost 1).

There’s one thing that Georgie says everyone will say about the MacDougalls.

“They’re really great people,” he said.

“They deserve to do really well.”

(Illustration: Demetrius Robinson / The Athletic; Photos: Daniel St. Louis / CHL)