Health

Mozzies may be carrying Japanese encephalitis this summer. Here’s what to know if you’re spending time outdoors

There’s no widespread dengue, yellow fever or malaria. But there are still many viruses that local mosquitoes can spread. Despite predictions of a rare mid-summer return of La Niña, there’s still speculation about what this means for temperature and rainfall. We may not see flooding, but there is still likely to be enough water around […]

There’s no widespread dengue, yellow fever or malaria. But there are still many viruses that local mosquitoes can spread.

Despite predictions of a rare mid-summer return of La Niña, there’s still speculation about what this means for temperature and rainfall. We may not see flooding, but there is still likely to be enough water around for mosquitoes.

After its unexpected arrival, it now seems Japanese encephalitis virus is here to stay. But how this virus interacts with local mosquitoes and wildlife, under the influence of increasing unpredictable climatic conditions, requires more research.

Mosquito-borne diseases in Australia

You can get better protection by also covering up with a long-sleeved shirt, long pants, and covered shoes.

Japanese encephalitis virus was initially discovered in southeastern Australia during the summer of 2021–22, and the boom in mosquito and waterbird populations that followed flooding at the time contributed to its spread.

Meanwhile, Murray Valley encephalitis virus has been detected in sentinel chicken flocks – which health authorities use to test for increased mosquito-borne disease risk – in NSW and in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

Some regions of Australia may have experienced flooding, but for many regions of the country, conditions have been hot and dry. This is bad news for mosquitoes.

About 5,000 cases of mosquito-borne disease are reported in Australia each year. The vast majority of these are due to Ross River virus. The disease this virus causes is not fatal, though it can be severely debilitating.

This summer, Japanese encephalitis virus has been detected in mosquitoes and feral pigs in NSW. The virus has also been detected in environmental surveillance in northern Victoria, and we know at least one person has been affected there.

In the summer of 2023–24, hot and dry summer conditions returned, mosquito numbers declined, and the number of cases of disease caused by Japanese encephalitis virus and Murray Valley encephalitis dropped.

A/Prof Cameron Webb/NSW Health Pathology

The influence of weather patterns

So why are Japanese encephalitis virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus active again when the conditions appear to be less favourable?

Outbreaks in southeastern Australia often accompany flooding brought on by La Niña weather patterns. Floods provide ideal conditions for mosquitoes, as well as the waterbirds that harbour the virus.

The symptoms of human disease caused by these two viruses are similar.

Japanese encephalitis virus is closely related to Murray Valley encephalitis virus. Mosquitoes pick up both viruses by biting waterbirds. But Japanese encephalitis virus has only recently become widespread in Australia.

So what is Japanese encephalitis, and how can you protect yourself and your family if you live, work or are holidaying in mosquito-prone regions this summer?

It’s unusual to see activity of these viruses when conditions are relatively dry and mosquito numbers relatively low.

After flooding rains brought on by La Niña in 2020, conditions that persisted for three years, Murray Valley encephalitis virus returned and Japanese encephalitis virus arrived for the first time.

Wherever you live, mosquito bite prevention is key. Apply insect repellent when outdoors, especially during dawn and dusk when mosquitoes are most active or at any time of the day if you’re in bushland or wetland areas where numbers of mosquitoes may be high.

Additional deaths have been reported due to Murray Valley encephalitis in recent years – two each in Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

What’s different this summer?

There also isn’t any evidence of more waterbird activity. In fact, numbers have declined in recent years.

For Japanese encephalitis virus, it may be that feral pigs are playing a more important role in its spread. We know numbers are on the rise and with drier conditions, perhaps mosquitoes and feral pigs, and other wildlife, are gathering together where they can find bodies of water.

The public health alerts in Victoria and NSW focus especially on specific regions in northern Victoria and around Griffith and Narromine in NSW where the virus has been detected.

There’s no specific treatment for either disease, though there is a vaccine for Japanese encephalitis which may be appropriate for certain people at high risk (more on that later).

Most people infected show no symptoms. In mild cases, there may be fever, headache and vomiting. In more serious cases, people may experience neck stiffness, disorientation, drowsiness and seizures. Serious illness can have lifelong neurological complications and, in some cases, the disease is life-threatening.

There have been around 80 cases of disease caused by these two viruses combined over the past four years. This includes seven deaths due to Japanese encephalitis across Queensland, NSW, South Australia and Victoria.

Now both viruses appear to be back. So what’s going on?

This news comes after both Victoria and New South Wales issued public health alerts in recent weeks warning about the virus.

There is no evidence that mosquito numbers are booming like they did back when La Niña brought floods to the Murray-Darling Basin.

But there is no vaccine available for Murray Valley encephalitis or Ross River viruses.

How can you reduce your risk this summer?

Relative to other parts of the world, Australia has traditionally been very low risk for potentially life-threatening mosquito-borne diseases.

A Victorian man is reportedly in a critical condition in hospital after contracting Japanese encephalitis from a mosquito bite.

Disease caused by two other pathogens, Japanese encephalitis virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus, are much rarer but potentially fatal.

If you live or work in areas at risk of Japanese encephalitis, seek advice from your local health authority to see if you are eligible for vaccination. Residents in specified local government areas in affected regions in both states are currently eligible for a free vaccine.

Murray Valley encephalitis virus has been known in Australia for many decades. After a significant outbreak across the Murray Darling Basin region in 1974, activity has generally been limited to northern Australia.

Health

Illinois’ first measles case of 2025 confirmed, health officials urge vaccination

CHICAGO – Illinois health officials have confirmed the state’s first measles case of the year, but they say the risk to the public remains low. What we know: The Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) confirmed on Wednesday that an adult in far southern Illinois tested positive for measles—the first case reported in the state […]

CHICAGO – Illinois health officials have confirmed the state’s first measles case of the year, but they say the risk to the public remains low.

What we know:

The Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) confirmed on Wednesday that an adult in far southern Illinois tested positive for measles—the first case reported in the state this year. The diagnosis was made through laboratory testing, and at this time, it’s not considered an outbreak.

The individual received care at a local clinic, which is working with IDPH and local health officials to identify any possible exposure. Staff at the clinic were masked and considered immune, and the clinic is reviewing the immune status of any potentially exposed patients.

The general risk of community transmission remains low, but IDPH says it will keep the public informed of any new developments.

“This first reported case of measles in Illinois in 2025 is a reminder to our Illinois residents that this disease can be prevented with up-to-date vaccination,” said IDPH Director Dr. Sameer Vohra.

What we don’t know:

IDPH has not shared additional details about the affected individual, including their age and whether it’s a man or woman.

What’s next:

People who may have been exposed—and are not immune—are advised to monitor for symptoms such as rash, high fever, cough, runny nose, or red-watery eyes.

If symptoms appear, which could take up to 21 days, residents should contact a healthcare provider before visiting a clinic or hospital to prevent potential spread.

Dig deeper:

Illinois hasn’t seen any measles cases since a 2024 outbreak in Chicago that infected 67 people.

Meanwhile, outbreaks in Texas and New Mexico have totaled over 680 confirmed cases, including three deaths, two of which were children, according to reports.

IDPH is reminding residents—especially travelers and those with unvaccinated children—to check their MMR vaccine status. Two doses are 97% effective in preventing measles, according to Dr. Vohra.

The state’s new Measles Outbreak Simulator Dashboard helps parents and schools assess vaccination coverage at individual schools, part of a broader effort to prepare for potential outbreaks.

Big picture view:

Vaccination rates have declined nationally since the COVID-19 pandemic, raising concerns among public health officials about the resurgence of preventable diseases like measles.

For more information about measles, visit the IDPH or CDC’s websites.

The Source: The information in this article was provided by the Illinois Department of Public Health.

Health

Dengue Outbreaks

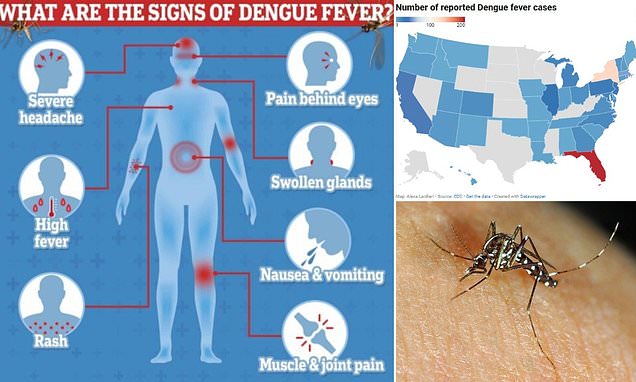

Dengue is one of the most common vector-borne viral diseases today, with ongoing outbreaks in Asia and Latin America. Its spread to North America highlights its global significance, as climate change and global warming increase the likelihood of its expansion into previously unaffected regions. With the development and availability of new vaccines, policymakers must determine […]

Dengue is one of the most common vector-borne viral diseases today, with ongoing outbreaks in Asia and Latin America. Its spread to North America highlights its global significance, as climate change and global warming increase the likelihood of its expansion into previously unaffected regions.

With the development and availability of new vaccines, policymakers must determine which are most suitable for at-risk populations. This session, presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) 2025 in Vienna, Austria, explored the geographic distribution, clinical presentation, treatment algorithms, and potential use of current dengue vaccines.

In Brazil, dengue follows a seasonal pattern, peaking during the rainy season from October to May. Most cases occur in adults aged 20-59 years, with deaths primarily affecting individuals with comorbidities or those older than 60 years. Since 2010, all four serotypes have been circulating, but dengue virus (DENV) serotypes 1 (DENV-1) and 2 (DENV-2) have been most common recently.

However, 2024 has seen an unprecedented epidemic in terms of both case numbers and duration. Changes in dominant serotypes are believed to contribute to the surge in infections and shifts in disease severity.

In this context, controlling the dengue epidemic means reducing infectivity and protecting vulnerable individuals. Since mosquito vector control is complex and no specific treatment for dengue exists, vaccines are the key preventive tool. Expanding vaccine availability and including travelers in the susceptible population are crucial steps.

The speaker’s team at this conference, from the Butantan Institute in São Paulo, Brazil, has been involved in the development of one of these vaccines. It is a tetravalent live-attenuated vaccine that covers all four dengue serotypes. The vaccine originated from the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases at the US National Institutes of Health, which licensed it to interested partners for further development. In 2018, Merck Sharp & Dohme Pharmaceuticals Ltd. and the Butantan Institute began a collaboration to advance the vaccine.

The ongoing phase 3 trial is a single-dose, placebo-controlled study that has enrolled more than 16,000 participants, who will be followed for a total of 5 years. The primary goal is to assess efficacy through polymerase chain reaction diagnosis of symptomatic dengue cases and to monitor for any potential vaccine-related adverse effects.

An interim analysis was conducted after 2 years of follow-up. Data are presented for DENV-1 and DENV-2, as these were the most prevalent during the latest epidemic, with no cases of DENV serotypes 3 or 4 detected during the study period.

- When considering DENV-1 and DENV-2 together, without differentiating participants’ serological status, the vaccine’s efficacy was 79.6%. After adjusting for prior dengue infection, efficacy increased to 89.2% compared with 73.6% in seronegative individuals.

- For DENV-1, without adjusting for serostatus, efficacy was 89.5%, reaching 96.8% in participants with prior dengue exposure and dropping to 85.6% in those without prior exposure.

- For DENV-2, without adjusting for serostatus, efficacy was 69.6%, rising to 83.7% in participants with prior dengue exposure and falling to 57.9% in those without prior exposure.

- Systemic adverse effects were common (58%), though severe reactions were rare. Their frequency increased with age. The most reported adverse effects included headache, rash, and itching across all age groups, while the most frequent local reaction was pain at the injection site.

One of the vaccine’s key advantages is that it requires only a single dose, making it ideal for outbreak situations and enabling a rapid response. Although it is pending approval by the Brazilian government, it is expected to begin administration this year. It will take at least 5 years to produce enough doses to vaccinate the entire country.

This story was translated from Univadis Spain using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOP PICKS FOR YOU

Health

Track the spread of measles in Texas

Audio recording is automated for accessibility. Humans wrote and edited the story. See our AI policy, and give us feedback. Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news. The number of cases reported in Texas’ historic measles outbreak has risen to […]

Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

The number of cases reported in Texas’ historic measles outbreak has risen to 624 cases in 26 counties, as of April 22. Of those, 64 patients have been hospitalized and two school-aged children have died since the outbreak began in January.

More than half of the cases so far have occurred in Gaines County, where the first case was reported on Jan. 29. As of Tuesday, 27 more cases have been reported since the state’s last update on Friday. Bailey, which has two cases, is the latest county to be added to the outbreak list, bringing the total to 26.

The Texas Department of State Health Services updates the number of infections and other details about the West Texas outbreak every Tuesday and Friday. By mid-April, the state health agency’s response to the outbreak, which includes a public awareness campaign, testing and vaccination clinics, has cost $4.5 million.

The most effective way to prevent contracting measles is to obtain two doses of the the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, which research has shown time and time again is safe. Side effects are mild and rare, according to health experts.

It is not known how the outbreak began. But this region includes pockets of high numbers of unvaccinated individuals.

What is measles?

Measles is a virus that spreads through respiratory droplets passed through the air by breathing, coughing and sneezing. It is one of the most contagious viruses transmissible between humans — 90% of unvaccinated people will get measles if they are exposed. People infected with measles are contagious four days before they begin showing rash symptoms, and the virus can stay active in the air for up to two hours, making hospitals, schools and day cares especially high-risk.

People infected with measles can experience high fever, cold symptoms like a cough or runny nose, watery eyes and a rash all over the body. While most people recover at home, it can lead to serious complications and even death, especially among young children, pregnant women and those with compromised immune systems.

Patsy Stinchfield, the former president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, worked in pediatric medicine for 45 years. She oversaw three measles outbreaks in Minnesota during her career, and said they were among the sickest children she ever treated.

“They come into the emergency room and they are literally ragdolls hanging over their parents’ shoulders, limp, dehydrated, miserable,” she said. “They’re barely even crying, because they’re so dehydrated they don’t have tears.”

How do you prevent measles?

There is an extremely safe vaccine that is over 97% effective in preventing measles. The MMR vaccine protects from measles, mumps and rubella, while the MMRV vaccine also protects against varicella, or chickenpox.

Most people receive the first dose when they are 12 months old, and a second dose when they are around 5 years old, although that can be shifted earlier if there is an active outbreak.

If you are not fully vaccinated, or are unsure if you are fully vaccinated, you can get the first shot now and achieve a significant degree of immunity within two weeks. The second shot, which delivers 97% immunity, can be given 28 days after the first shot, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

If you are unvaccinated and believe you’ve been exposed to measles within the last 72 hours, getting a vaccine can lessen the impact of the illness. People who cannot receive the vaccine, such as infants, pregnant women and severely immunocompromised people, may be treated with immunoglobulin within six days of exposure to lessen symptoms.

Once someone has contracted measles, the only treatment is managing symptoms and preventing more serious complications, such as pneumonia.

Since the measles vaccine was not a requirement to attend school until 1980, some older adults are questioning whether they have immunity.

Dr. Peter Hotez, the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, has pointed to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation that if people are unsure of their immunity, they should first check their vaccination records.

If there’s no record of measles immunity, individuals should get vaccinated with the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. According to the CDC, there’s no harm in getting another MMR vaccine, even if you may already be immune to measles.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says outbreaks are more likely when the vaccination rate in a community falls below 95%.

Can you get sick if you’re vaccinated?

A small percentage of people who have been infected in this current outbreak report being fully vaccinated, according to DSHS.

While people who are fully vaccinated can still contract measles, they are not at risk for severe illness and are much less likely to spread the virus. According to the CDC, people with both vaccine shots, those who have previously had measles or those who were born before 1957 are presumed immune from measles.

Has anyone died during this outbreak?

On Feb. 26, a school-aged child, who was unvaccinated, died after being hospitalized the week prior, according to state officials. The child’s family lives in the outbreak area.

On April 3, an unvaccinated 8-year-old girl, who also lived in the outbreak area, died of measles, according to hospital officials.

State officials have not confirmed when the last person in Texas died from measles prior to 2025.

Where else in Texas have there been measles cases this year?

There have been four additional cases of measles this year that are not being counted in the above totals because they are not considered part of the West Texas outbreak. Two cases were reported in Houston in January, one was reported in February in Rockwall County involving an adult who had traveled internationally and another was reported in February in Austin involving an unvaccinated infant who became infected while traveling overseas. The baby’s parents were vaccinated and local officials do not believe anyone else locally had been exposed.

Austin officials said it was its first measles case in 24 years.

“The time we have been preparing for is here,” Austin Mayor Kirk Watson said during a news conference. “I want to emphasize to everyone listening that vaccination remains the best defense against this highly contagious and deadly disease.”

Watson said there is an effort to raise the vaccination rate in Travis County, including through low-cost or free programs like Shots for Tots, Big Shots, and mobile clinics. Travis County had the lowest percentage of kindergarteners with the measles vaccine — 89.6% — among Texas counties with at least 100,000 people, according to 2023-24 state data.

“We are here to simply say measles can kill, ignorance can kill, and vaccine denial definitely kills,” U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett said during the news conference.

Do we know how measles arrived in Gaines County?

Texas Department of State Health Services officials say they do not know that information yet.

I thought we fixed measles. What happened?

The measles vaccine is one of the great achievements in modern medicine. It is so effective, and was so widely adopted, that the U.S. declared measles eliminated in 2000. But as anti-vaccination sentiment increased, vaccination rates dropped and the disease made a resurgence.

While the vast majority of children in the U.S. get the MMR vaccine on time, certain communities have shied away from it for religious or cultural reasons, creating pockets of vulnerability for the virus to take hold. In 2017, Minnesota saw a measles outbreak in their growing Somali community, and in 2019, measles tore through the Orthodox Jewish community in New York City and neighboring counties, eventually infecting more than 650 people.

In Texas, the virus has concentrated in the Mennonite community in Gaines County. One of the county’s local public school districts, with only 143 students, has the highest school vaccine exemption rate in the state — 48% of Loop school district students have conscientious exemptions from required vaccinations. In 2023-24, less than half of all Loop kindergartners — 46% — were given the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, according to state data.

Two other school districts in Gaines County had higher vaccination rates. Seagraves, with 512 students, had 94% of its kindergartners vaccinated against measles and Seminole, with 2,976 students, had 82% of its kindergartners vaccinated.

In tight-knit communities with low vaccination rates, a measles outbreak should be “somewhat expected,” said Kathleen Page, an associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

But vaccination rates have been dropping nationally and in Texas, well beyond these communities that have traditionally abstained, leaving a wider swath of the population open to infection. In 2019, almost 97% of Texas kindergartners were vaccinated against measles, compared to 94% in 2024, according to the CDC.

When was the last time Texas had a measles outbreak?

In 1992, Texas had an outbreak that grew to 990 cases. That was the last outbreak larger than this. Although in 2013, there was an outbreak with 27 cases and in 2019, an outbreak with 23 cases.

This is a 99.9% decrease from the pre-vaccine high point, in which almost 86,000 Texans got measles in 1958.

What do we know about Gaines County’s Mennonite community?

The tight-knit Mennonite community in Gaines County, mostly centered around the town of Seminole, have been hardest hit. Members of this Anabaptist religious order aim to maintain separation from the modern world, in language, school and dress.

They settled in West Texas from Mexico in 1977, drawn there because “large blocks of land were available, population was not concentrated, and private schools were not heavily regulated,” according to the Texas State Historical Association.

Many of the families home-school or send their children to small private schools, and do not maintain regular contact with the health care system, Texas Department of State Health Services spokesperson told Anabaptist World. Mennonites, and their Anabaptist brethren, the Amish, had very low uptake of the COVID vaccine.

Who is most vulnerable to measles?

Infants under the age of 12 months who haven’t yet been vaccinated, pregnant women and immunocompromised children are extremely vulnerable to measles and should take extra precautions during an outbreak.

In Ector County, where an infant fell ill with measles, health department director Garcia commended the family for taking action to get their child tested.

“A lot of times measles can be hard to detect as a parent,” Garcia said. “This mother did everything I would do – she took him to the doctor, and as he didn’t get better, she took him back. That’s when they did the testing.”

These vulnerable populations are not protected by the vaccine the way most children and adults are, so they’re relying on everyone else to keep them safe, Stinchfield said. Especially when it comes to babies, “they’re voiceless,” she said.

“They can’t say, ‘Everyone get vaccinated.’ They don’t get a say, but they’re the ones that are the first to suffer the consequences,” she said. “The community around them are the ones that are supposed to put those shields on and encircle them and protect them by protecting themselves.”

How bad can measles symptoms get?

Dozens of Texans have been hospitalized with measles in Texas. Some have been able to be treated in Gaines County, while others have been sent to Lubbock for a higher level of care, Albert Plinkington, CEO of the Seminole Hospital District, told Texas Standard.

Many people hospitalized for measles can be treated for dehydration and fever, and then sent to recover at home. But in serious cases, children may need higher levels of care. Stinchfield said she had a patient end up on a ventilator in the intensive care unit for 15 days. They survived, but will have lifelong medical complications due to the damage to their lungs.

“Those of us who have stood next to that child in an ICU fighting measles, need to express to parents how devastating it is for the parent and how much regret they have,” she said.

What are state and local agencies doing to manage this?

The Texas Department of State Health Services is working with the South Plains Health District and Lubbock Public Health, as well as local hospitals and health care providers, to manage the outbreak. The state is assisting with contact tracing, in which they try to identify who may have been in contact with someone who tested positive, and letting them know they have been exposed.

They are encouraging unvaccinated people who have been exposed to isolate for 21 days, and if it is within 72 hours of the exposure, get vaccinated to offset some of the symptoms. The South Plains Public Health District is offering measles vaccines at their clinic in Seminole. Approximately 100 people had been vaccinated in recent days, a DSHS spokesperson said in February.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also announced on March 4 that officials were in Texas to help local leaders respond to the outbreak. Those extra personnel will provide support for one to three weeks.

Suddenly standing up a measles response takes a huge amount of time and effort from state and local health authorities. It can cost between $2.7 million and $5.3 million to respond to a measles outbreak, according to the CDC, compared to the relatively negligible cost of vaccinations.

“If you were to put this in front of ‘Shark Tank,’ they’d say, ‘Wow, this is the best deal. We definitely need to do something that is so successful, so cost effective and averts spending money that we don’t want to spend, and saves lives. Let’s go for it,’” she said. “That’s the way that our legislators need to think about this as well.”

By mid-April, the state health agency’s response to the outbreak, which includes a public awareness campaign, testing and vaccination clinics, has cost $4.5 million.

Disclosure: Texas State Historical Association has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Tickets are on sale now for the 15th annual Texas Tribune Festival, Texas’ breakout ideas and politics event happening Nov. 13–15 in downtown Austin. Get tickets before May 1 and save big! TribFest 2025 is presented by JPMorganChase.

-

College Sports1 week ago

College Sports1 week agoFormer South Carolina center Nick Pringle commits to Arkansas basketball, John Calipari

-

Sports4 months ago

Sports4 months agoClaims of 'greed' as cricket figures divided by plans for major Test shake

-

Sports5 months ago

Sports5 months agoStephanie Gilmore’s break from competitive surfing

-

Fashion6 months ago

Fashion6 months agoNike Revamps Leadership with New Heads of Sports Marketing and Legal Under CEO Elliott Hill

-

College Sports5 months ago

College Sports5 months agoNCAA Division II Women’s Volleyball Championships 2024

-

Sports5 months ago

Sports5 months agoWho is ROSÉ’s ‘Toxic Till the End’ former partner? Fans are guessing Jaden Smith, Skater Boys, and others.

-

Technology5 months ago

Technology5 months agoTechnology in Education: An Overview

-

Motorsports5 months ago

Motorsports5 months agoMaroon 5, Eminem, and Bagatelle Festival: Abu Dhabi F1 Grand Prix Weekend Lineup