NIL

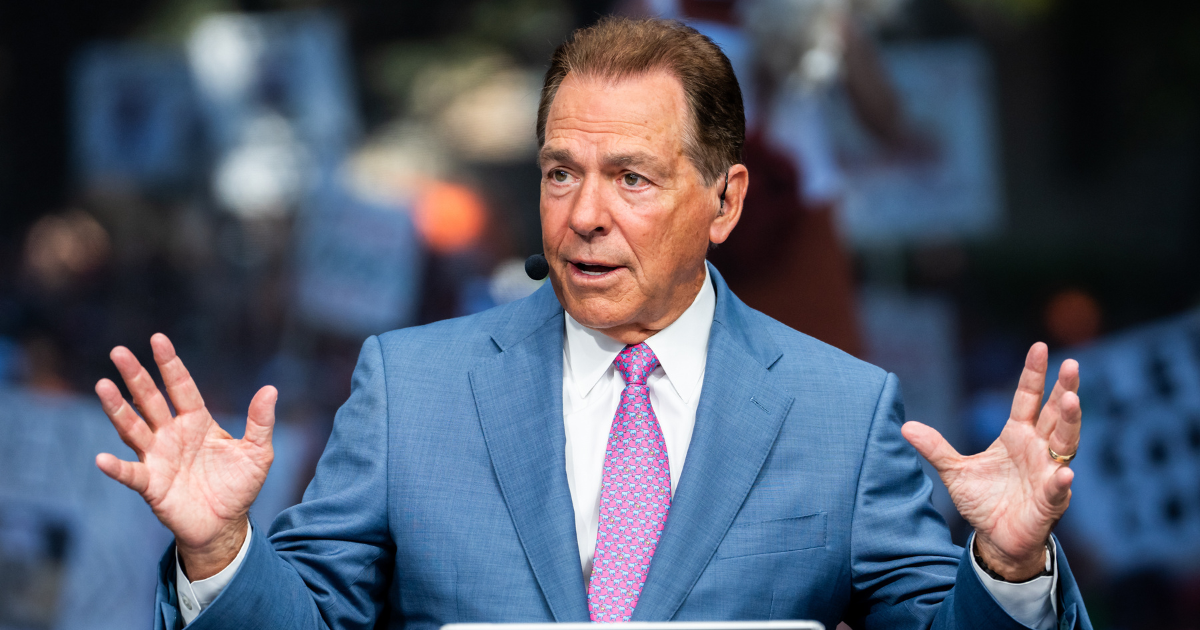

Nick Saban rejects notion he’s anti-NIL ahead of presidential commission on college sports

There’s been plenty of news around a potential presidential commission to investigate and solve some issues in college athletics. Nick Saban isn’t sure such a commission is needed.

He does, however, want to make it clear that he’s willing to lend his support to any party looking to create those solutions. And, moreover, he reiterated he’s not against NIL in general, though it is one of the issues the sport is grappling with.

“I’m not anti-NIL. I’m all for the players making money,” Nick Saban said at a charity event. “I don’t think we have a sustainable system right now. I think a lot of people would agree with that. In terms of the future of college athletics period, not just football, how do we sustain 20 other non-revenue sports that create lots of other opportunities for people in the future?”

Those are the questions the long-time college football coach is willing to lend his support on. It just may not happen in the way it was initially reported.

“I know there’s been a lot of stuff out there about some commission or whatever,” Nick Saban said. “I don’t think we need a commission. I’ve said that before. I think we know what the issues are, we just have to have people that are willing to move those and solve those, create some solutions for some of those issues.”

Again, he’s willing to help. However things shake out, whether it’s a political body or the NCAA or conferences themselves, change appears to be coming in the sport.

Who better to tap into for advice than Nick Saban? He knows quite a bit.

“I’m all for being a consultant to anybody who would think that my experience would be beneficial to help them create some of those solutions,” Nick Saban said. “President Trump is very interested in athletics, he’s very interested in college athletics. He’s very interested in maintaining the idea that people going to college create value for their future in terms of how they develop as people, as students, as well as having a balanced, competitive playing field.

“So if I can be a consultant to anyone to help with the future of college athletics I’d be more than happy to do that.”

NIL

How much do college football transfers earn in the NIL and revenue-sharing era?

Since the transfer portal opened last week, there has been plenty of wheeling and dealing between teams and agents.

Now that schools can pay players directly, as a result of the House v. NCAA settlement, general managers work feverishly to manage eight-figure payrolls (in the Power 4, or seven-figure roster budgets at most Group of 5 schools) to construct winning teams. That usually means spending significant money on transfers, who can provide a more immediate impact than a high school recruit. Look at the 2025 Heisman Trophy winner, Indiana quarterback Fernando Mendoza — a transfer from Cal — as a perfect example of why programs mine the portal.

Third-party name, image and likeness (NIL) deals, which were the primary method of compensating players from 2021 through mid-2025, still play a role, especially as the most well-resourced schools push the envelope and send roster budgets skyward, above the $20.5 million cap that was initially established last summer.

But what do transfers cost? Exact compensation numbers are hard to come by because of confidentiality agreements in contracts and schools’ desires to keep them close to the vest for a competitive advantage. To get an idea of what this year’s portal market looks like, The Athletic surveyed industry experts, including general managers, personnel staffers and agents, on the ranges of compensation that transfers receive. All subjects were granted anonymity for their candor.

General managers stress that transfers are more expensive than traditionally recruited and developed players because of the immediate impact they provide. High school recruits typically receive much less compensation, according to a recent survey by The Athletic, and front office staffers say retention is often more cost-effective than going into the portal.

The ranges below represent what teams expect to pay for what they consider good, solid Power 4 starters in the transfer market, but values vary depending on a team’s roster budget, the player’s role, the scarcity of the position in the market and how a team values positions. And there are always outliers on both ends of the spectrum.

Here’s what we learned.

QBs still get the most, and the market may be going up

- QB range: $1 million to $4 million, but potentially higher for the top players

For the most part, Power 4 starting quarterbacks were the highest-paid players on a roster in 2025. In the previous portal cycle, the floor for a Power 4 starter was around $750,000, while the top of the market reached as much as $3.5 million annually, for quarterbacks like Duke’s Darian Mensah and Miami’s Carson Beck. But most of the known 2025 quarterback contract figures ranged from the high six figures to around $2 million. Basically, for $1 million or a little bit more, a team could sign a good, solid Power 4 starting quarterback.

This portal cycle, it appears prices are going up. The floor for a Power 4 starter, in most cases, is $1 million. “If you don’t spend a million, you ain’t getting ’em,” one Power 4 GM said. There will be some exceptions, especially for mid-tier Power 4 programs that don’t go over the cap and sign G5 or FCS transfers. Those players are likely to get upper six figures.

But the top end of the market is growing. The most desirable QBs in the portal, like Cincinnati’s Brendan Sorsby and Arizona State’s Sam Leavitt, are expected to draw offers of $4 million or more. A second Power 4 GM said he suspects offers could reach $5 million for those two. One Power 4 personnel director called the top end of the QB market “insane.”

Drew Mestemaker, the North Texas transfer who led the FBS in passing yardage and committed to Oklahoma State Saturday, is receiving a two-year, $7.5 million contract, according to the Tulsa World. Mestemaker is expected to make $3.5 million in 2026 and $4 million in 2027, according to that report.

Beyond the top five or six quarterbacks in the portal, the next tier figures to fall into a range anywhere from $1.5 million to around $3 million.

Drew Mestemaker committed to Oklahoma State on Sunday and will earn a reported $3.5 million next season. (Danny Wild / Imagn Images)

Offensive tackles and defensive linemen also cost a premium

- OT range: $600,000 to $1.3 million

- Edge rushers: $500,000 to $2 million

- Interior DL: $500,000 to $1.5 million

The positions that protect and affect the quarterback are in the next tier of costs, just like in the NFL.

The men who protect the quarterback are highly valued and their numbers are also going up this portal cycle. A Power 4 GM who is in the market for tackles said that it’s difficult to get a good one for $500,000 and placed the floor around $600,000 to $650,000.

“Good offensive tackles, you’re looking at a minimum of $750,000,” said a Power 4 front office staffer. The top-tier tackles are likely to clear seven figures and approach $1.2 or $1.3 million.

Transfer edge rushers can get pricey, too. Good starting pass rushers usually range anywhere between $500,000 and $1.5 million, though there have been a few outliers who have been higher than that. Texas Tech edge rusher David Bailey, who led the FBS in pressures this year, was believed to have received more than $2 million in 2025.

South Carolina edge rusher Dylan Stewart decided to return to the Gamecocks, but had he entered the portal, it’s believed he could have drawn offers of $2 million or more. A general manager at a school who is losing a top-tier pass rusher expects that his departing star will get above $2 million from his next school.

There are starting defensive ends who could go for as low as $250,000, though those are typically going to be more for starters in name only who rotate frequently and don’t play the volume of snaps that some of the top pass rushers do.

Solid interior defensive linemen typically start around half a million and can quickly get into the upper six figures, “but the elite guys can get around $1.5 (million),” an agent said, citing two top defensive tackles who received $1.6 million in 2025.

Offensive skill positions vary widely

- RB range: $400,000 to $900,000

- WR range: $500,000 to $1 million

- TE range: $300,000 to $900,000

NFL teams typically spend less on running backs than on any other non-specialist position group, but that’s not the case in college football. Teams value running backs more, and it appears the ceiling for running backs is rising in this portal cycle. Some of the top backs who intend to enter the portal, like NC State’s Hollywood Smothers or North Texas’ Caleb Hawkins, are expected to receive high six-figure offers.

“There’s 136 FBS teams, and if everyone is using two backs regularly, that means people are trying to find 272 good running backs,” a Group of 5 GM said. “I’m not sure there are as many good backs as teams are looking for, so schools are willing to pay more.”

Starting backs who rotate more cost less and can even be below $400,000

Receivers are the most expensive of a quarterback’s skill-position supporting cast, but compensation varies depending on role. A transfer expected to be a team’s No. 1 receiver is likely to get high six figures. Elite transfer receivers can get seven-figure offers.

Auburn’s Cam Coleman, the top receiver in the portal and arguably the best available player regardless of position, could get expensive quickly, especially since the teams hosting him for official visits — Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and USC — are all deep-pocketed programs. The Power 4 front office staffer suggested Coleman’s baseline offers may start at $2 million and go up from there based on the teams involved.

A transfer expected to be a team’s No. 2 receiver who has proven production is likely to get paid closer to $500,000.

Tight ends have largely remained consistent with the range of the previous cycle. Many will cost under $500,000, and some P4 teams were able to get solid ones last year for less than $200,000. How a tight end is utilized, and their importance in the offense, play a role in how teams value them. Some teams would rather not spend a ton for one if they can justify it. But TEs who are athletic, dynamic pass catchers and are attractive draft prospects can get above $700,000 and push close to seven figures.

Defensive backs have similar floors but varying ceilings

- Cornerbacks: $250,000 to $1 million

- Safeties: $250,000 to $900,000

The compensation ranges for defensive backs can vary quite a bit because of how differently they can be used in defensive schemes. Across the board, top-tier boundary cornerbacks (who line up against outside receivers) are highly valued and, in this portal cycle, are seeing numbers as high as the upper six figures. “The really good ones will get $1 million, but the majority will fall in the $300,000 to $800,000 range,” a Power 4 GM said.

A good quality starter can get mid-six figures. From there, it can vary. “It’s a pretty wide range for corners just because of how many teams use it,” a player agent said.

Is your nickel back more of a true third cornerback or a hybrid safety/outside linebacker who plays on the edge of the box? That factors into what a team will spend on the position. Nickel backs are considered more affordable and are on the low end of the cornerback range. A hybrid safety/outside linebacker, if he’s a true impact player, can get high six figures.

Safety is a place where some front offices spend less, unless it’s an elite top-end player. There are a few top safeties whose deals surpassed $800,000 this year, but for the most part, teams have looked to spend a little less than what they have for corners.

Linebackers and interior offensive linemen tend to be the most affordable

- Linebackers: $200,000 to $750,000

- Interior OL: $200,000 to $700,000

In last year’s cycle, linebackers were the most affordable position to obtain a starter in the portal, with the floor being around $150,000 and the ceiling usually falling just below $500,000.

Those rates have ticked up going into this year’s cycle. The floor is closer to $200,000 or $250,000. The ceiling varies. One Power 4 GM said a linebacker “has to be elite to get more than $500,000,” while another GM said some are going for as high as $700,000. Having a pair of starting linebackers between $300,000 and $500,000 isn’t unusual.

The baseline for starting interior offensive linemen is usually between $200,000 and $300,000, with the higher end usually topping out at around $500,000 or $600,000. Scheme plays a role here, too. If it’s a run-heavy team that asks a lot of its guards, that could push the value up into the $700,000 or $800,000 range for top-end players. And the ceiling for centers is considered to be around $600,000 or $650,000.

What are Group of 5 programs paying transfers?

The rates for transfers who sign with Group of 5 schools are much lower because roster budgets are much smaller than at their Power 4 counterparts. While Power 4 programs’ football roster budgets can range from $13 million up to $30 million, G5 schools mostly ranged between $1 million and $10 million in 2025.

The vast majority of Group of 5 schools have roster budgets below $5 million, with a few exceptions. The top spending schools in the American, like USF, Memphis and Tulane, are believed to be above that.

Because of those budgets, you won’t find seven-figure players at G5 schools. Quarterbacks get the most, usually topping out around $500,000 or $600,000. One Group of 5 GM, whose school will have roughly a $3 million roster budget, said he expects to pay between $300,000 and $400,000 for his top quarterback transfer target this cycle.

Typical starting running backs and tight ends will top out around $200,000 to $250,000. High-end receivers can be a little bit more, around $300,000. The top going rate for G5 offensive tackles is around $300,000 to $400,000.

The ceiling for defensive linemen is around $250,000 to $300,000. For linebackers and defensive backs, the ceiling tops out around $150,000 to $200,000.

While those are high-end rates, the floor for most players in the Group of 5 is in the five figures.

It’s harder to find a consensus because Group of 5 roster budgets vary so much. Teams in the American usually have bigger budgets than those in Conference USA or the MAC, where five-figure player compensation rates are more the norm.

And though most Power 4 players receive some form of revenue sharing or NIL money, that’s not the case at the Group of 5 level, where some are paying extra — above and beyond a scholarship — to only a portion of their roster.

NIL

Brendan Sorsby commits to Texas Tech: Cincinnati transfer QB joins Red Raiders

Cincinnati transfer quarterback Brendan Sorsby has committed to Texas Tech, CBS Sports’ Chris Hummer and Matt Zenitz report, choosing the Red Raiders after a quick visit schedule that also included LSU.

Sorsby is rated as the No. 2 quarterback and the No. 2 overall transfer prospect in this cycle in the 247Sports transfer rankings.

Sorsby’s decision keeps him in the Big 12 and gives Texas Tech an experienced option at quarterback after a season that ended with lingering questions at the position. The Red Raiders won the Big 12 Championship for their first out-right conference title since 1955 but struggled offensively in their College Football Playoff quarterfinal loss to Oregon at the Orange Bowl, where Behren Morton was unable to generate much production in a 23-0 shutout.

Drew Mestemaker commits to Oklahoma State: Former North Texas QB joins coach Eric Morris in Stillwater

Cody Nagel

Texas Tech has already demonstrated a willingness to be aggressive in the transfer portal, using resources and NIL opportunities to target impact players at positions of need. Sorsby’s addition signals that the Red Raiders are prepared to continue that approach, blending proven experience with a roster built to compete at the highest level of the conference.

How Sorsby fits with Texas Tech

Sorsby joins a room that includes rising sophomore Will Hammond, who suffered a torn ACL this season. While he could be ready for the start of 2026, Sorsby provides immediate experience and the option for Hammond to gain more experience in a backup role before taking over the reins in 2027.

When Sorsby initially made his decision to enter the transfer portal, there was speculation he could also explore the NFL Draft after a breakout season that put him on the radar as a potential early-round pick. Instead, he appears ready to return to college for a final year, giving him an opportunity to further refine his game and improve his draft stock.

Sorsby will arrive at Texas Tech with three years of starting experience and a track record of production at the Power Four level, though team success has varied. He is 13-17 (.433) as a starter in his career, including a 1-6 mark at Indiana as a redshirt freshman in 2023. After that season, he transferred to Cincinnati ahead of the 2024 campaign and went on to establish himself as one of the Big 12’s more efficient passers across two seasons with the Bearcats.

Sorsby does it with arm, legs

During his time at Cincinnati, Sorsby passed for 5,613 yards and 45 touchdowns, completing 62.9% of his passes. He led the Big 12 in yards per completion (13.5) this season. He showed consistent command of the offense early in the season, including a seven-game stretch without an interception. Sorsby matched a career-low with only five picks in 12 games this season. He earned second-team All-Big 12 honors.

Sorsby also adds value as a runner, becoming more involved in the ground game as his career progressed. He finished this year at Cincinnati with a career-high 580 rushing yards on 100 carries and nine rushing touchdowns, matching his total from the previous season. While Cincinnati closed the year with four straight losses and his passing efficiency dipped late, his overall body of work made him one of the most sought-after quarterbacks in the portal.

NIL

IU football picks up commitment from Wisconsin transfer safety Preston Zachman – The Daily Hoosier

Wisconsin transfer safety Preston Zachman is headed to Indiana according to multiple Sunday reports.

The 6-foot-1 and 212-pound Zachman will be entering his seventh and final season of college football in 2026.

He has played in 35 career games (20 starts, nearly 1,500 snaps), all with Wisconsin, and has 130 tackles and seven interceptions.

Zachman will help fill the void to be left by starters Louis Moore and Devan Boykin.

In 2025 Zachman played in three games and had 12 tackles and two interceptions. He missed the final nine games of 2025 due to a leg injury. Both of the takeaways came in the second half of the season opener against Miami (Ohio). Zachman was named Big Ten defensive player of the week.

Zachman is seeking a medical hardship waiver to play the seventh season in 2026. After only playing three games, he should qualify.

In 2024 he started all 12 games at safety for the Badgers and made a career-high 58 tackles (39 solos), two interceptions, three TFLs and four pass breakups.

In 2023 Zachman played in all 13 games, making five starts. He totaled 49 tackles and two interceptions.

In 2022 Zachman played in six games before missing the rest of the season due to injury. He had 11 tackles and 0.5 TFLs, and grabbed his first career interception in the season opener vs. Illinois State.

In the 2020 season that did not count against eligibility, Zachman played one game. He didn’t play at all in 2021 and took a redshirt season.

Out of Southern Columbia H.S. in Elysburg, Pa., Zachman was a three-star high school recruit by 247 Sports, ESPN and Rivals in the class of 2020.

More transfer portal information:

For complete coverage of IU football recruiting, GO HERE.

The Daily Hoosier –“Where Indiana fans assemble when they’re not at Assembly”

Related

NIL

Under Armour announces first ‘Click-Clack’ class of NIL deals

Following this weekend’s Under Armour All-America Game, the brand announced its first “Click Clack” NIL class. Under Armour signed six highly rated recruits to NIL deals.

Notre Dame safety signee Joey O’Brien, BYU quarterback signee Ryder Lyons, Maryland EDGE signee Zion Elee and Alabama safety signee Jireh Edwards are all part of the group, Under Armour announced Sunday. Two touted 2027 recruits – Texas wide receiver commit Easton Royal and four-star wide receiver Eric McFarland – are also on board.

SUBSCRIBE to the On3 NIL and Sports Business Newsletter

All six players competed in the Under Armour All-America Game on Saturday. O’Brien and Royal were two of Rivals’ top performers in the game, which took place at Spec Martin Stadium in Orlando, Fla.

“I think you hear us coming,” Under Armour wrote in its Instagram post. “Meet the inaugural Click-Clack Class — Under Armour’s first NIL squad.”

Under Armour capitalizing on star power

Ryder Lyons previously announced an NIL deal with Under Armour in September 2025 after committing to BYU. The four-star quarterback signed with BYU, but will embark on a one-year mission and will not enroll at school until the following January. He is the No. 5-ranked quarterback from the 2026 cycle, according to the Rivals Industry Ranking.

As a whole, Under Armour’s Click-Clack NIL class features four of the top 50 players in the nation out of the 2026 cycle. With Easton Royal and Eric McFarland, the brand also has two of the top 25 prospects in 2027.

The group includes some of the highest-profile high school football players, as well. Zion Elee’s $687,000 On3 NIL Valuation is the highest of the group and ranks No. 11 in the high school football NIL rankings. Lyons also sits at No. 13 with a $656,000 On3 NIL Valuation.

The On3 NIL Valuation is calculated by combining Roster Value and personal NIL. Roster value is the value an athlete has by being a member of his or her team at his or her school, which factors into the role of NIL collectives. NIL in an athlete’s name, image and likeness and the value it could bring to regional and national brands.

NIL

The NCAA further fails high schoolers with G League Rulings

If the road to college basketball scholarships was not already difficult for high school players, the NCAA’s decision to allow NBA G League athletes to enter or re-enter college basketball has created another obstacle. One of the most impactful rulings of 2025, the policy arrives at a moment when NIL and the transfer portal have already reduced access to scholarships and roster spots. By granting G League players immediate eligibility, the NCAA further dilutes opportunities for first-time college athletes.

G League to College: The Precedent Is Already Set

The first notable example of this shift was Thierry Darlan. Darlan spent two seasons in the G League, appearing in 58 games. He suited up for Ignite during the 2023–2024 season and later joined the Delaware Blue Coats in 2024–2025. He was not on the fringe of the league. Instead, he emerged as a legitimate contributor and started roughly half of his games.

Despite that professional experience, Santa Clara granted Darlan eligibility for the West Coast Conference. Because Santa Clara carries a limited national profile, his return to college basketball drew little attention.

That changed when the NCAA restored eligibility for London Johnson at a true “blue blood,” the University of Louisville. Johnson’s case sparked national outrage and forced the college basketball world to confront a new reality. Players could now return to NCAA competition after playing in the NBA G League. The trend continued in November when BYU signed Abdullah Ahmed, a former player for the G League’s Westchester Knicks.

James Nnaji Pushes the Boundary Even Further

Baylor’s signing of James Nnaji brought the issue into sharper focus. Nnaji was selected 31st overall in the 2023 NBA Draft and later became part of an NBA trade in 2025. His move back to college basketball showed just how far the boundaries had shifted.

NCAA Responds as Backlash Grows

As concerns mounted, NCAA President Charlie Baker addressed the issue publicly.

“The NCAA has not and will not grant eligibility to any prospective or returning student-athletes who have signed an NBA contract,” Baker said. “As schools increasingly recruit individuals with international league experience, the NCAA is exercising discretion in applying the actual and necessary expenses bylaw. This ensures that prospective student-athletes with experience in American basketball leagues are not at a disadvantage compared to their international counterparts. Rules have long permitted schools to enroll and play individuals with no prior collegiate experience midyear.”

High School Players Were Already Losing Ground

Even before these rulings, opportunities for high school athletes were shrinking. The transfer portal now functions like free agency. As a result, Division I coaches-including those at HBCUs-often prioritize experienced transfers over developing high school talent. A brief review of HBCU Division I rosters highlights the impact.

Transfer Numbers Tell the Story

According to Real GM, a basketball tracking service, 99 MEAC players transferred from other institutions. In the SWAC, that number rises to 161. Together, those 260 roster spots no longer exist for high school athletes. Football numbers paint an even starker picture.

NIL Is the Driving Force

So what draws these players back to college? NIL.

The financial landscape has changed dramatically. In many cases, college athletes now earn more through NIL than NBA G League players earn through salaries. High-profile exceptions exist, such as Bronny James, whose endorsement portfolio-often linked to his father, NBA legend LeBron James-sets him apart.

BYU star AJ Dybantsa reportedly earns $4 million this season. Texas Tech’s JT Toppin is also positioned for a $4 million payday. When combined with what Duke’s Cooper Flagg earned last season, NIL compensation now exceeds typical NBA rookie salaries and far surpasses G League pay.

The Illusion of a Safety Net

NIL rumors have also fueled speculation about college athletics as a financial safety net. One widely circulated but unconfirmed report suggested Ohio State supporters planned to offer wide receiver Marvin Harrison Jr. more money than he would earn as a first-year NFL player. The goal was to keep him in school.

Harrison ultimately declared for the 2023 NFL Draft and was selected fourth overall by the Arizona Cardinals in 2024.

HBCUs Feel the Same Pressure

HBCUs face the same challenges and must “keep up with the Joneses.” The first nationally televised SWAC matchup of the season illustrated that reality. Bethune-Cookman defeated Florida A&M 87–83 in a high-level contest loaded with transfers.

Bethune-Cookman’s Arterio Morris, a transfer from Texas, scored 20 points. Florida A&M’s Jaquan Sanders, a transfer from Hofstra, led all scorers with 22. Most key contributors in the game came from the transfer portal.

Of the 28 total players on both rosters, only eight came directly from high school. That number even includes prep school players, who are not always truly straight out of high school. Florida A&M’s roster consists of roughly one-third high school players. Bethune-Cookman’s roster sits closer to one-quarter.

A Broader Concern Across College Sports

Across all sports, coaches increasingly worry that athletes prioritize NIL opportunities over skill development. Many cite this shift as a factor in the retirement of one of college football’s greatest coaches, Nick Saban.

After a historic run at Alabama, Saban stepped away from the program. During a roundtable discussion in Washington, D.C., led by U.S. Senator Ted Cruz, Saban explained his frustration.

“All the things that I believed in for all these years, 50 years of coaching, no longer exist in college athletics,” Saban said. “It was always about developing players. It was always about helping people be more successful in life.”

What Comes Next?

Baker closed by emphasizing that while the NCAA has lost control in several legal battles, it does not plan to concede this one.

“I will be working with DI leaders in the weeks ahead to protect college basketball from these misguided attempts to destroy this American institution.”

So what’s next? Perhaps LeBron James-who never played college basketball-and Bronny James-who left early and spent time in the G League-will enroll at the University of Arizona to play alongside Bryce.

At this point, what would stop them?

The post The NCAA further fails high schoolers with G League Rulings appeared first on HBCU Gameday.

HBCU Gameday

This story was originally published January 4, 2026 at 12:08 PM.

NIL

Player of the Year Star QB Bolts College Football Playoff Team for Big 12

Getty

The college football transfer portal is heating up with a wave of early moves.

One star quarterback from the College Football Playoff has already found a new home after entering the transfer portal. As the final four teams battle for the national championship, the rest of the country is focused on the college football transfer portal.

Fresh off a career season, former James Madison quarterback Alonza Barnett entered the portal and found a new team in a matter of days. Barnett is headed to the Big 12 announcing his decision to join UCF where the dual-threat signal-caller is the early favorite to be the Knights starter. The quarterback is expected to replace Tayven Jackson.

Barnett threw for 2,806 yards, 23 touchdowns and eight interceptions while completing 58.4% of his passes in 14 appearances for JMU in 2025. The quarterback also added 589 rushing yards and 15 touchdowns on the ground as well.

Beyond impressive stats, Barnett led James Madison to a Sun Belt championship as JMU crashed the College Football Playoff party. Barnett was named the Sun Belt Player of the Year in 2025.

Here’s what you need to know about the latest college football news.

New UCF QB Alonza Barnett Is Projected to Have a $321,000 NIL Value

NIL deals are not made public, but Barnett’s value is projected at $321,000, per On3. During Scott Frost’s first season in his second stint at UCF, the Knights struggled with volatility at quarterback. After transferring from Indiana, Jackson failed to provide consistent play at the position in 2025.

“Quarterback is no different than other positions,” Frost said on December 10, 2025, per On3’s Brandon Helwig. “In a perfect world, we’re developing them all in-house. We didn’t have the opportunity to do that much last year because I got here after Signing Day. So this is really our first step in trying to recruit some building blocks at several positions, quarterback certainly being one.

“If you were experiencing this every day and seeing the drama and the price tags that go along with transfer quarterbacks, it’d certainly benefit us to have a homegrown one. I love the two guys that we got. We’re going to pour into them and try to build somebody that we can keep for a while.”

Transfer Portal Rumors: Arizona State’s Sam Leavitt & Cincinnati’s Brendan Sorsby Among the Top QBs Searching for New Teams

Amid star quarterbacks like Arizona State’s Sam Leavitt and Cincinnati Brendan Sorsby in the portal generating buzz, Barnett has flown a bit under the radar. Barnett gives UCF a dynamic dual-threat quarterback that Frost covets in addition to having College Football Playoff experience, even if James Madison’s CFP game against Oregon did not go as planned.

The quarterback may not have consistently played elite competition at James Madison, but the signal-caller performed well against the best team’s on JMU’s schedule. Barnett threw for 273 yards and two touchdowns against Oregon in the College Football Playoff. The dual-threat quarterback also added 45 rushing yards and TD on the ground.

Jonathan Adams is a veteran sports contributor covering the NFL, NBA and golf for Heavy.com. His work has been prominently featured on NFL.com, Yahoo Sports, Pro Football Talk, CBS Sports, Bleacher Report and Sports Illustrated. More about Jonathan Adams

More Heavy on College Football

Loading more stories

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoRoss Brawn to receive Autosport Gold Medal Award at 2026 Autosport Awards, Honouring a Lifetime Shaping Modern F1

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoDowntown Athletic Club of Hawaiʻi gives $300K to Boost the ’Bows NIL fund

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoPrinceton Area Community Foundation awards more than $1.3 million to 40 local nonprofits ⋆ Princeton, NJ local news %

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoKentucky AD explains NIL, JMI partnership and cap rules

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoThree Clarkson Volleyball Players Named to CSC Academic All-District List

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoYoung People Are Driving a Surge in Triathlon Sign-Ups

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoBeach Volleyball Unveils 2026 Spring Schedule – University of South Carolina Athletics

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoWhy the NIL era will continue to force more QB transfers

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoIs women’s volleyball the SEC’s next big sport? How Kentucky, Texas A&M broke through

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoNew college football program emerges as landing spot for Dylan Raiola