“To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift.”

“It’s not who’s the best—it’s who can take the most pain.”

“Somebody may beat me, but they are going to have to bleed to do it.”

These are just three of many memorable quotes by Steve Prefontaine that encapsulate the long-distance runner’s relentless spirit. Fierce, outspoken, and stubborn, Pre pushed the boundaries of the sport not with record-breaking times but also with his manner of winning, giving every race a maximal effort. He competed in the 5,000-meter event at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich and held the American record in every distance from 2,000 to 10,000 meters between 1973 and 1975. He was the first track athlete to sign with Nike, setting a precedent for brand deals. He played a significant role in popularizing the sport, his charismatic style and bravado drawing thousands of fans to the bleachers.

And then, on May 30, 1975, at only 24, Pre’s life was cut short in a car crash.

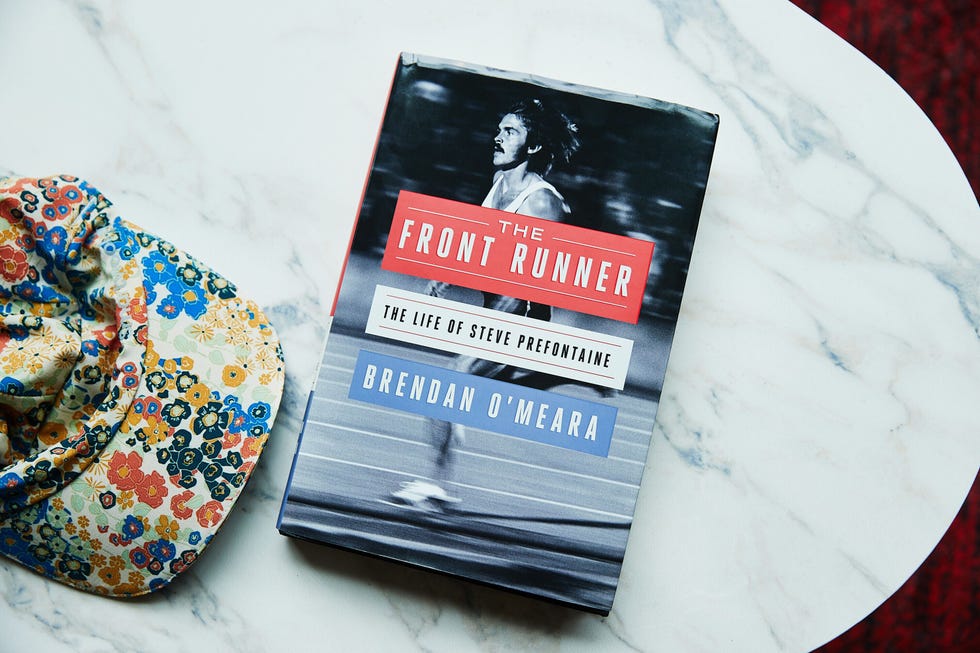

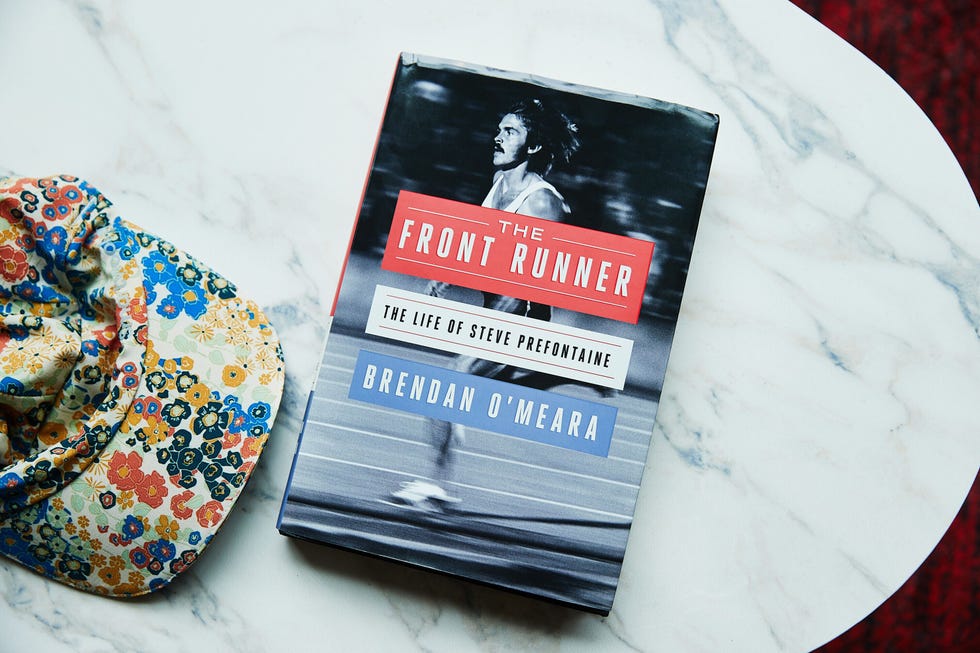

Five decades after the tragedy, his legacy still inspires runners all around the world. Brendan O’Meara’s new book, The Front Runner, offers a contemporary retelling of Pre’s meteoric rise to fame. Just ahead of the book’s launch, the author and host of The Creative Nonfiction podcast shared with Runner’s World why he decided to write the biography and why Pre remains one of America’s most iconic runners.

Mariner Books “The Front Runner: The Life of Steve Prefontaine” by Brendan O’Meara

So much has been written about Pre already. How is your book different?

My book recasts him in a modern light. What’s going on with name, image, and likeness in college sports really reflects what he was dealing with in the early 70s, trying to be compensated. Pre was very forward-thinking and trying to fight for athlete empowerment and rights at a time when athletes had little power—or didn’t realize how much power they actually did have—because of the amateur establishment of the day. Mike O’Hara launched the International Track Association in 1973 as a real professional track, but if athletes signed with ITA, they were no longer amateurs and couldn’t run in the Olympics, and a lot of them felt very conflicted. So that’s kind of the world-building aspect that helped inform this particular Prefontaine story.

I was able to find a couple of hundred people who overlapped with him, and a lot of them never spoke on the record. I went digging into what made Pre tick, to get to the man behind the myth because he’s been so lionized and deified. I wanted to write something more intimate.

What surprised you while reporting the story?

Pre has been characterized as very confident and brash. It was great to get a sense of how insecure he was at times, how much pressure he put on himself, which hasn’t been articulated very well in the past. He wanted to break 4 minutes in the mile at the Coos County Meet during his senior year. The mile was his white whale for the longest time. Close to 2,000 people were jammed in to watch from Coos Bay. He ran 4:06:09, amazing time. But his friend, Ron Apling, found Steve behind the stands crying after the race. Ron asked, ‘What’s the matter, Steve?’ And Steve said: ‘They all came to watch me break 4 minutes, and I failed them.’ He realized he was such a draw and would come to see himself as an artist, a performer.

Something else that surprised me was Pre coaching women, Mary Decker, Debbie Roth, and Caroline Walker. Just on his own time because he wanted to help. He was just counseling people in the community, writing them workouts in the same vein that his high school coaches Walt McClure and Phil Persian wrote for him.

RW Archives

RW Archives

What are some timeless lessons from Pre’s approach to training?

In that era, it was to pound you to death with miles, and if you couldn’t withstand that mileage, you just weren’t cut out for it. But Bill Bowerman, head track coach at the University of Oregon, had a credo that it’s better to undertrain than overtrain an athlete. Bowerman and his assistant coach Bill Dellinger, both Steve’s college coaches, were very much ahead of the game in that regard, and I think that’s very applicable today.

Pre was on the vanguard of sports psychology, of goal setting. There’s a great image in Geoff Hollister’s book about him trying to get to the sub-4 in the mile and break 9 minutes in 2 miles. Writing it down was his way of trying to manifest it as best as possible. It gave him a better sense and a crystallized vision that if you thought about it and visualized it enough, you might be able to get there.

What part of the book was the hardest to write?

Pre’s final day on the planet, trying to track every step of the way and making sure it tracks with the police and other reports. I wanted to handle that scene with care and fairness, lay it out without judgment, just paint the scene. Pre always felt so alive to me, and then I’d think, ‘Oh my god, he’s gonna die.’ Through my rewriting and research, I’d go through a different archive, and he’d come alive to me again, feel so vibrant, and as I’d be getting closer to 1975, I’d think, ‘He’s gonna die again.’ It’d be a gut punch for me.

NCAA Photos//Getty Images

NCAA Photos//Getty Images

Is there anything you wish had made it into the book but was cut?

One scene I was sad to see go was from the 1972 indoor season. The Los Angeles Times did a split prediction and split column with Harley Tinkham, their track and field writer. They had an astrologer, Burton Morse, predict the outcome of the races based on the runners’ birth signs and all that stuff. Morse said that the stars weren’t in Prefontaine’s favor. It was just so wild that in 1972, when track and field was so popular, and Pre was an ascendant Olympian, and Jim Ryun was trying to reclaim his fame, they’d take their track expert and pit him up against an astrologer. In the Sports Illustrated article, where I read about it, they cleaned up the language. But Pre pretty much said, ‘Fuck the stars.’

Have you speculated about what would happen if Pre lived and his career went on? Where would he end up?

I think he’d have just gone on to be a tremendous ambassador for track and field, especially being Nike’s firstborn and athlete. Some of his friends said he’d have gone into politics, born with the wild charisma he had. So many people said, ‘He just had it.’ He had magnetism about him. He would have been a tremendous leader and champion.

Bettmann//Getty Images

Bettmann//Getty Images

How is Pre still such a household name in running? Why does he matter in 2025?

It was something cosmic. A sport only has so many inflection points. Track and field was ready for a change. Pre had the look, the moxy, the talent. He had Bowerman and he had Nike. And it was just a moment. He was the catalyst, ready to ride that rocketship. There have been far more talented and charismatic people who shattered world records since, but they don’t inspire us or fire us up the way Steve did. That’s why he’ll probably forever tower over track and field.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mariner Books “The Front Runner: The Life of Steve Prefontaine” by Brendan O’Meara

Pavlína Černá, an RRCA-certified run coach and cycling enthusiast, has been with Runner’s World, Bicycling, and Popular Mechanics since August 2021. When she doesn’t edit, she writes; when she doesn’t write, she reads or translates. In whatever time she has left, you can find her outside running, riding, or roller-skating to the beat of one of the many audiobooks on her TBL list.

0

(@EWUWBB) May 20, 2025