James Madison was close to rounding out its 2025-26 roster and playing host to Ike Cornish and Justin McBride, a pair of former power conference players who were once four-star recruits ranked in the top 100 of their high school classes.

A couple of weeks earlier, the JMU women had a pair of SMU transfers — Kylie Marshall and Bri McLeod — on campus.

McLeod was one of the top players out of Canada in high school while Marshall was a top-40 player in the United States according to ESPN.

In the old days — before the House settlement, plans for revenue sharing and other direct payments to players for their services — that was the kind of news that had a way of leaking.

Even if those players hadn’t chosen the Dukes, which all four did, their official campus visits were good publicity.

Even being associated with high-level recruits was good for JMU’s brand.

But in 2025, it’s the dawn of a new era even as Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) has been around for almost half of a decade.

Their interest in James Madison was a closely guarded secret.

The fact they’d even been to Harrisonburg wasn’t public knowledge until after they’d announced commitments to the Dukes.

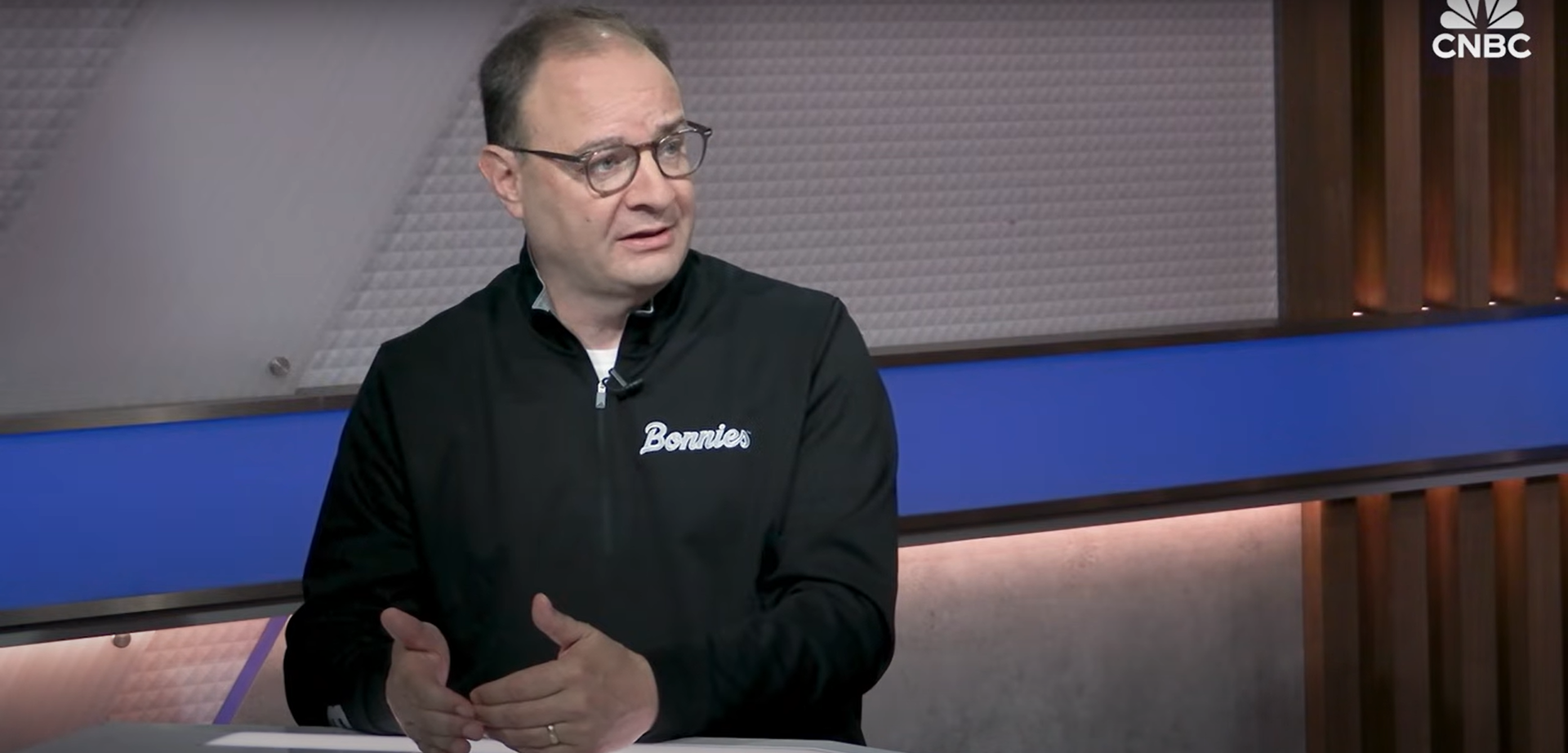

“It’s a different world right now,” JMU men’s head coach Preston Spradlin said. “This stuff is so tricky now. Things have to be really tight.”

The concern that news of even mutual interest between player and school, particularly when it comes to proven and experienced transfers, is twofold.

When it hits social media that the Dukes received a visit from a player, it’s not uncommon for said player to almost immediately receive a call from another program asking what JMU is offering to set off another round of negotiations.

Secondarily, other players may wonder if there’s money to go around if it appears a team is close to landing a transfer recruit.

Spradlin said even being listed among several programs that have talked to a player can lead to assumptions the recruiting process is further along than it is.

“To be honest, if it’s tweeted out that this kid was on campus, it could screw us with the next kid,” Spradlin said. “It’s so different. That’s just where it’s at. These coaches and agents try to use that stuff against you. The moment a kid tweets out that he’s coming here, another school will sweep in and say what’s the deal that you’ve got there, and try to offer him more.”

The recruiting visits themselves have changed, too.

Players and their families used to spend two days on campus with the JMU coaching staff guiding tours, showing off the basketball facilities and making sure they enjoyed Harrisonburg’s best restaurants and hotels.

If possible, the Dukes might schedule the visit to coincide with a big event, such as the spring football game, where the recruit could see and be seen by the fanbase.

Since the opening of the Atlantic Union Bank Center in 2020, more often than not, players who took an official visit to JMU later committed.

Some of those elements of the visit still exist, for sure.

But some official visits now last 24 hours or less, with a significant percentage of that time spent in a meeting room negotiating what amounts to a salary.

“This is what the difference is now between two years ago,” JMU women’s head coach Sean O’Regan said. “You still have to get to that portion of the visit where you sit down at a table. We also have to tell them, ‘Hey, understand what’s happening with the current team.’ And that’s not just about playing time now. In the past, in theory anyway, maybe you come in and you believe you can beat out the returning starter or the Player of the Year for playing time. Now it’s money, and maybe it’s a contract. And on our end, it’s loyalty to the players choosing to come back here.”

The evaluation process in recruiting has become not only observing a player’s potential to help on the court but also figuring out if their priorities line up with what JMU has to offer.

O’Regan said that while the Dukes are competitive financially with programs they recruit against, if the first thing a player brings up is money, that more or less ends the recruitment process for the women’s staff.

Spradlin agreed that taking time to figure out if a payday was the top priority could slow down the recruiting process.

“I can tell you our super power as a staff has always been evaluating and building great relationships in the recruiting process,” Spradlin said. “Not that that’s not important. It’s still very important to us, but it’s not quite as important to every kid out there. The ones that are coming here, it’s still important. But it’s taking a little bit longer to weed through and find the ones that are prioritizing that because of the influx of money.”

But, the new challenges aren’t unique to JMU’s programs.

And in the end, both the men’s and women’s teams filled their needs and essentially set their rosters for next season before most of their Sun Belt Conference rivals.

Spradlin and O’Regan both said that while they are figuring out a new process, JMU still has advantages that should allow the Dukes to compete for conference championships each year.

“It’s not exclusive to us,” Spradlin said. “It’s not exclusive to men’s basketball. In recruiting, the things that were prioritized and important, those are still important. But they don’t rank at the top of the list for some kids. I’m not saying that for everybody. There are still kids who want to come here because JMU is an amazing degree, and they want to play for the best fans in the Sun Belt. They want to play for a championship coaching staff, but then again there’s other kids who that’s not quite as important for any more because they can get more money somewhere else.”