GAINESVILLE, Fla. – Florida volleyball announced Wednesday that outside hitter Kamryn (Kami) Chaney, middle blocker Brianna (Bri) Holladay and outside hitter

Selena Leban will join the Gators for the upcoming 2026 season.

Arriving for the spring 2026 semester, Holladay and Leban each bring one year of collegiate experience, while Chaney arrives with three.

“Selena and Bri are talented freshmen who offer both production and upside,” Florida Head Coach

Ryan Theis said. “Kami gives us a proven point scorer and while we’ll add a few more pieces between now and August, we’re thrilled with this start.”

The trio joins incoming freshman opposite/outside hitter Nadi’ya Shelby as newcomers on Florida’s 2026 roster.

Details on Chaney, Holladay and Leban are below.

Kamryn (Kami) Chaney

- Position: Outside Hitter

- Class: Senior

- Height: 6-1

- Hometown: Park Forest, Illinois

- Previous Teams: Vanderbilt (2025), Princeton (2023-24)

- High School: Marist

At Vanderbilt

Honors:

- TSWA Volleyball Player of the Week – Sept. 23

- Recorded a double-double vs. UC Irvine (19 kills/11 digs)

- Black Student-Athlete Group Executive Board – Treasurer

2025 as a junior: Saw action in 17 matches and led the Commodores attack 12 times and behind the service line in eight matches… Finished with double-digit kills 12 times, including three with 20 or more… Season-best 22 kills against California (Sept. 10)… Matched career-best six aces against Western Kentucky (Sept. 16)… Led Vanderbilt in aces with 33 and totaled 218 kills, .182 hitting %, 94 digs,25 blocks and 264.5 points…Averaged 4.01 points per set, 3.30 kills per set, 0.50 aces per set, 1,42 digs per set and 0.38 blocks per set

At Princeton

Honors:

- Ivy League Player of the Year (2024)

- First Team All-Region (2024)

- First Team All-Ivy League (2024)

- Ivy League All-Tournament Team (2024)

- #9, Most Kills in A Season (421, 2024)

- Second Team All-Ivy League (2023)

- 4x Ivy League Player of the Week (Nov. 18 2024, Nov. 4 2024, Oct. 21 2024, Sept. 16 2024)

- Ivy League Rookie of the Week (Oct. 16, 2023)

2024 as a sophomore: Led the Ivy League and ranked 16th nationally in points-per-set (5.20) … led the Ivy league and ranked 24th nationally in kills-per-set (4.43) … led the Ivy League in points (494) and kills (421) … ranked second in the Ivy League in service aces (48) and service aces-per-set (0.42) … her season-high 34 kills that came on a .484 hitting percentage against High Point on Sept. 21 were the eighth-most kills recorded in a five set match by any player in the 2024 season … became the first Ivy League player Maddie Lord of Penn of Penn on Oct. 11, 2014, to have 34 kills in a match … recorded 12 double-doubles … exceeded 20 kills in eight matches … tallied 25 kills, a season-high 16 digs and a season-high seven blocks on Sept. 13 against St. John’s … recorded 25 kills on a .532 hitting percentage, 13 digs and two service aces against Yale on Nov. 1 … accumulated 24 kills on a .404 hitting percentage and four digs against Yale on Oct. 5 … had 24 kills, hit .358 and had four digs on Sept. 28 against Penn … contributed 23 kills on a .400 hitting percentage and 11 digs at Cornell on Oct. 19 … finished with 22 kills, 10 digs and three blocks at UMBC on Sept. 21 … compiled 20 kills on a .357 hitting percentage, 10 digs and four blocks on Nov. 16 at Harvard

2023 as a freshman: Led the Tigers and ranked second in the Ivy League in points per set (3.86) … led the Tigers and ranked fourth in the Ivy League kills per set (3.27) … led the Tigers and ranked 10th in the Ivy League in service aces per set (0.33) … tied the team-high and ranked 10th in the Ivy League in service aces (24) … appeared in 21 matches and 73 sets … recorded 42 digs and 32 blocks … had a season-high 25 kills on a .417 hitting percentage in the Tigers’ win over Dartmouth on Nov. 10 … recorded 17 kills, three digs and two service aces at Harvard on Oct. 6 … finished with 16 kills, five service aces and three digs in the Tigers’ win at Dartmouth on Oct. 7 … tallied 13 kills, a season-high six service aces, four digs and three blocks on Oct. 14 in Princeton’s win over Cornell … finished with 15 kills, four digs and three blocks at UMBC on Sept. 8 … had a season-high four blocks in the Tigers’ victory over Penn on Sept. 22 … had double digit kills in 13 matches

Why Chaney chose the University of Florida

“Florida checked all the boxes for me. They have the best combination of elite academics and high-level athletics which is super important for me. How could I say no to Gainesville and the opportunities Florida can bring? Go Gators!”

| Career Stats |

| Year |

S |

MP |

Kills |

E |

TA |

Hit. Pct. |

A |

SA |

SErr |

D |

BS |

BA |

TB |

BErr |

PTS |

| 2023 |

73 |

21 |

239 |

126 |

650 |

0.174 |

2 |

24 |

34 |

47 |

6 |

26 |

32 |

2 |

282.0 |

| 2024 |

95 |

26 |

421 |

151 |

968 |

0.279 |

16 |

40 |

62 |

222 |

10 |

46 |

56 |

5 |

494.0 |

| 2025 |

66 |

17 |

218 |

113 |

578 |

0.182 |

6 |

33 |

67 |

94 |

2 |

23 |

25 |

3 |

264.5 |

| Totals: |

234 |

64 |

878 |

390 |

2,196 |

0.222 |

24 |

97 |

163 |

363 |

18 |

95 |

213 |

10 |

1,040.5 |

Brianna (Bri) Holladay

- Position: Middle Blocker

- Class: Sophomore

- Height: 6-3

- Hometown: Leesburg, Va.

- Previous Teams: Virginia Tech

- High School: Riverside

At Virginia Tech

Honors:

- Earned All-Tournament Team honors at both the Blue Hen Invitational and the Seahawk Classic

- Named MVP of the Hokie Invitational

2025 as a freshman: In her rookie campaign, the Leesburg, Va., native appeared in 30 of Virginia Tech’s 31 matches, recording 108 blocks. She led the Hokies in blocks in 12 matches and posted five or more blocks 11 times during the season. Holladay added three double-digit kill performances and recorded her first career double-double with a career-high 13 kills and 10 blocks in Virginia Tech’s season finale against Syracuse on Nov. 28.

High School: Earned First Team All-State, All-Region and All-District selections in 2024… Named the 2024 State Player of the Year… Earned 2024 County Player of the Year honors and was named First Team All-Metropolitan… Earned Earned First Team All-State, All-Region and All-District selections in 2023… Named to the Second Team All-Metropolitan in 2023… Is an AP Scholar with Distinction… Earned the Academic Excellence Award four times.

Why Holladay chose the University of Florida

“I chose Florida Volleyball because the program represents a legacy of excellence that inspires every player to set a higher standard. I value the opportunity to represent Florida on the court and develop under the guidance of the new coaching staff. The passionate Gator fan base and strong support for student-athletes create an environment where I know I will be pushed to excel. Beyond athletics, the university’s strong academic reputation, particularly in engineering, will prepare me for a career after volleyball.”

| Career Stats |

| Year |

S |

MP |

Kills |

E |

TA |

Hit. Pct. |

A |

SA |

SErr |

D |

BS |

BA |

TB |

BErr |

PTS |

| 2025 |

95 |

30 |

158 |

49 |

332 |

.328 |

5 |

7 |

12 |

20 |

10 |

98 |

108 |

12 |

224.0 |

| Totals: |

95 |

30 |

158 |

49 |

332 |

.328 |

5 |

7 |

12 |

20 |

10 |

98 |

108 |

12 |

224.0 |

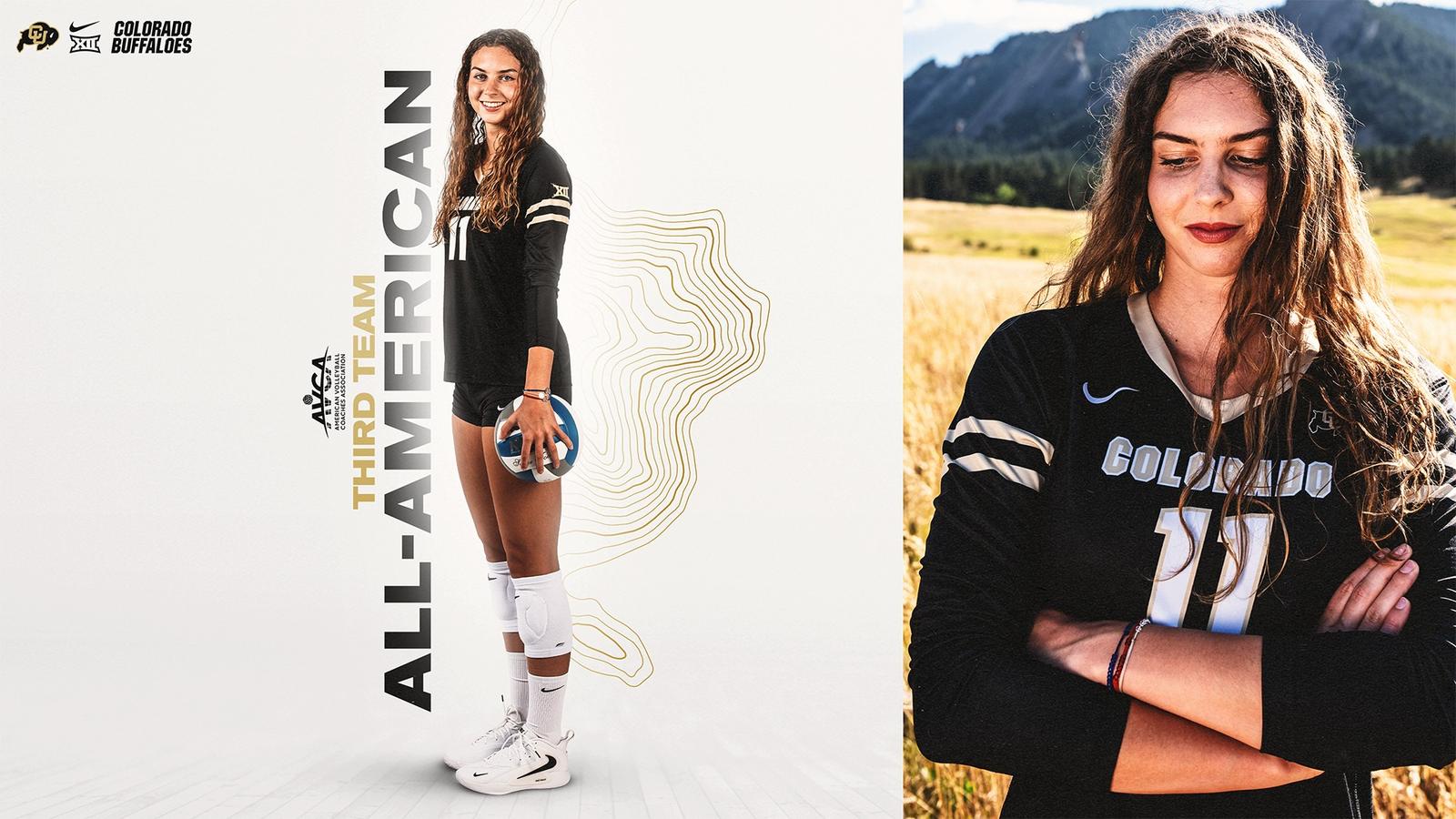

Selena Leban

- Position: Outside Hitter

- Class: Sophomore

- Height: 6-0

- Hometown: Nova Gorica, Slovenia

- Previous Teams: Kansas

- High School: Gimnazija Šiška

At Kansas

2025 as a freshman: Appeared in 21 of the Jayhawks’ 35 matches, posting double-digit kills seven times and double-digit digs four times. Recorded back-to-back double-doubles, including a career-best 20 kills and 11 digs against then-No. 2 Penn State on Aug. 25, followed by 14 kills and 10 digs against then-No. 8 Wisconsin on Aug. 29.

High School: Competed for Slovenia on the national stage since 2019, beginning with the U16/U17 European Championship…. The European Golden League in 2024 was her 10th competition within the European Volleyball Confederation (CEV)… In 42 career CEV matches, Leban has recorded 289 kills, 52 service aces and 32 blocks…. Also competed in the 2020 and 2023 European Cups for her club.

| Career Stats |

| Year |

S |

MP |

Kills |

E |

TA |

Hit. Pct. |

A |

SA |

SErr |

D |

BS |

BA |

TB |

BErr |

PTS |

| 2025 |

67 |

21 |

147 |

74 |

425 |

.172 |

11 |

15 |

32 |

126 |

1 |

28 |

29 |

5 |

177.0 |

| Totals: |

67 |

21 |

147 |

74 |

425 |

.172 |

11 |

15 |

32 |

126 |

1 |

28 |

29 |

5 |

177.0 |

FOLLOW FLORIDA VOLLEYBALL

FloridaGators.com

Instagram | Facebook | X