When Matt Crocker landed in America, as U.S. Soccer’s second-ever sporting director, he plunged into a few urgent tasks. In 2023, he had a men’s national team coach to hire and, soon, a USWNT coach to find too. He had 27 national teams to oversee, and his first priority, he has said, was “getting our own house in order.” But eventually, he stepped back — and saw deficiencies.

He asked Twenty First Group, a sport data firm, some simple questions: Over the past 10 years, how many of the world’s best soccer players have been American? From 2014 to the present, Crocker said, the data showed a “slight, slow decline” in top-50 and top-250 players on the women’s side. On the men’s side, Crocker asked a room of coaches in January, how many top-50 players do you think we’ve produced?

“Zero,” a man in the audience shouted.

“Correct,” Crocker said.

And “there’s a saying,” he later continued: “do what you’ve always done, and you will get what you’ve always got.”

His goal, and his most monstrous task, is to get American soccer doing things differently.

He knows, however, that he can’t do this alone. “What I pretty quickly realized,” Crocker tells The Athletic, “is that we can have a way of doing things, a philosophy internally; but the players that come to us are always gonna be the same players unless we impact the landscape.”

So he canvassed that landscape, the messy, “disjointed,” dollar-driven U.S. soccer landscape. Throughout his first year on the job, he listened and learned. Then he codified a vision, a “plan for changing and improving, hopefully, player development in this country,” he says. His challenge, and the riddle that no U.S. Soccer executive has ever solved, is implementing it at thousands of amateur clubs, across an alphabet soup of youth soccer sanctioning organizations, that he does not — cannot — control.

There, at the clubs, is where “95% of player development happens,” Crocker often says. That’s the theory and motto underpinning the plan, which he and U.S. Soccer have branded “the U.S. Way.” Crocker has thoughts on how a 13-year-old should train, and on how a 5-year-old should be introduced to the game. What he’s trying to figure out is how to transmit those thoughts to the actions of the 13-year-old’s and the 5-year-old’s coaches.

U.S. Soccer sporting director Matt Crocker heads the federation’s youth development initiative (Photo by Evan Bernstein/Getty Images)

In the past, he and others say, U.S. Soccer gurus would dictate to those coaches. The most transformative and disruptive plan to date, the Development Academy, relied on “standards” — and “technical advisors” who enforced them. A variety of “evaluation criteria,” from cadence of training to style of play, were graded and mandated at top youth clubs across the country. Many believe the DA reformed player development for the better, but it also angered members. “U.S. Soccer used a stick,” Crocker says, before relaying one analogy he heard on his listening tour. A stakeholder told him: “The only time we heard from U.S. Soccer is when they wanted to send a lightning bolt down to blow up something.”

Crocker, years later, has taken a different tack. Rather than dictate or tell, he wants to help and “influence.” He wants to inspire adoption of and alignment with his ideas. “It’s educating,” says Trish Hughes, commissioner of the Girls Academy, one of several youth leagues that Crocker needs on board, “and trying to pull people in to be a part of the process.”

But doing that, across this boundless landscape of independent clubs with their own incentives, who are often far more focused on fighting with one another for players than on producing future pros, is “not simple,” Crocker admits.

“The 5% is such an easy bit to change and tweak,” he said in January of U.S. Soccer’s operations. “But this 95% is a beast. A beast that I can’t even — I’m only just trying to begin to get my head around.”

Seven months later, he’s still trying. “This is — pfff,” he says with wide eyes. “This is something that I’ve never experienced.”

‘It feels like UEFA’

Crocker comes from a land where soccer is very different. Born in Wales, he made his name in England, first at Southampton, then at the English FA, the sport’s national governing body. There, he helped craft and operationalize “England DNA,” a five-pillar approach to elite player development that is credited with shaping successful England national teams of the 2020s.

But there, operationalizing a national plan is relatively straightforward.

“No one is more than three hours away from St. George’s Park,” Crocker says, referring to England’s national football center. “You could go on a roadshow, and cover the whole country, [visiting] every county association, in two weeks.” When the FA wants to push a new developmental philosophy or initiative, it engages with those county associations, which govern grassroots soccer; with professional clubs, which operate youth academies; and with coach educators, who work for the FA and serve the entire country. Everybody, and everything, can be interconnected.

In the U.S., on the other hand, everybody has their own motives. A youth club, which relies on pay-to-play fees for funding, must attract and retain players; a pro club might scout and poach those players; a college coach might recruit them so his or her team can win; Crocker might want them to develop into national teamers.

“What is needed to make youth soccer better can be very similar and very different to what pro soccer may need or want, or what the national team may need or want,” says Christian Lavers, president of the Elite Clubs National League (ECNL).

And in each of those segments, Lavers notes, “you have a lot of very strong-willed, very opinionated people.” Historically, “in American soccer,” he says, “there has really never been a table where youth soccer, pro soccer, college soccer and U.S. Soccer all sit together with transparent, respectful relationships to try and talk about moving the game forward. And so, what you end up having is all these different ecosystems of soccer pulling in slightly different directions based on what they see, and what they feel is important.”

(Photo by Adam Hagy/ISI Photos/USSF/Getty Images for USSF)

Even within the “youth soccer” category, there are multiple elite leagues for teens and multiple sanctioning bodies. Within the U.S. Youth Soccer Association, the largest sanctioning body, there are 54 state associations (two each in California, Texas, New York and Pennsylvania), each with its own season, own concerns and own structure. It’s a web of maddening complexity. “Sometimes it feels like 50 countries, it feels like UEFA,” Crocker says, referencing the European soccer confederation of 55 member nations. “It feels like trying to get the whole of UEFA on the same page with a philosophy. That is the bit that is our biggest challenge.”

He knows that he and the U.S. Soccer Federation, a national governing body with a budget less than half that of the English FA, cannot work hands-on with coaches in the same way England can, nor with clubs that span an area roughly 75 times as vast. They cannot identify, nurture and elevate all the best 13-year-old players.

They have discussed novel solutions, such as creating six or eight “regional youth national teams” to touch a broader selection of players, but remember: youth national teams are the 5%; “you guys are the 95%,” Crocker told the room of coaches in January. “Your ways are fundamentally gonna make the difference. … You make the sausage. We’re just a little machine at the end that turns.”

What Crocker and U.S. Soccer must do, essentially, is teach the sausage makers.

‘Putting the player’s needs above winning’

That’s why Crocker, in his second year on the job, set off on his own “roadshow.” He jetted coast to coast, south to north, evangelizing “the U.S. Way.” He presented at board meetings and symposiums. He spoke at conferences and conventions. The meat of his message was, and is, about “putting the player first, and the player’s needs above winning.”

For elite teenage prospects, that means individual development plans shared among youth national team and club coaches. U.S. Soccer is piloting a digital platform that will house performance data, training programs, film and more, so that all those coaches who sculpt a given player can align.

For 5-year-olds, of course, it means something very different. U.S. Soccer doesn’t have specific prescriptions for them — yet. Crocker, though, wants the federation to help shape playing environments at “every age and stage,” as he often says, “as soon as a child can walk.” He envisions a dad who signs his daughter up for rec soccer, and stumbles into coaching the team, with no prior experience. He wants that dad to log onto U.S. Soccer’s website and find instructive, illustrative answers to three key questions: “How do you make the environment fun and safe? How do you [give each kid] as many touches [of the ball] as you possibly can? And how do you make sure that you put the individual needs of the player before winning?”

That latter point, the prioritization of winning vs. development, is a source of constant tension in youth sports. There’s natural pressure to win, says Hughes, the Girls Academy commissioner, and “there’s always a scorecard in the girls youth soccer space,” where wins determine coach and club prestige. Crocker says it’s “a bit dog-eat-dog. It’s a bit ‘win win win, that helps me as a coach keep the players I want to keep, and helps me progress.’”

(Photo by Carmen Mandato/Getty Images)

Crocker believes, “wholeheartedly,” that this mentality hinders technical development, and must shift. Many others do as well. But there’s a significant subset of coaches who believe that the U.S. soccer intelligentsia has actually shifted too far toward “winning doesn’t matter.” Lavers, the ECNL president, is part of this subset and says: “We need to correct for that.”

“You cannot completely decouple winning and development,” Lavers argues. “Because the will to win, the fight to win, the understanding of what it takes to win, is something that you certainly don’t want to stifle.”

He adds: “I also think we need to have respect for the youth coaches, [and] respect that they know how to balance winning vs. development as it changes across all of the age groups, and not talk to them as if they can’t possibly understand that.”

This is the proverbial tightrope that Crocker must walk. He does not want to impose his views, but, in the absence of mandates or standards, how can he incentivize coaches to adopt them?

In January, he spoke about drafting a “bible” that anyone could choose to follow. Speaking now, via Zoom from a temporary office south of Atlanta, he delves into the more formalized field that will be crucial: coaching education. U.S. Soccer’s network of courses, educators and licenses has historically been exclusive. It’s “a drop in the ocean compared to what we’re gonna need to deliver to service the whole game across 50 countries,” Crocker says.

He knows that coaching coaches is unsexy. But it’s “the biggest lever that we can pull,” he says. In England, he explained, a young boy is “never more than 13 minutes away from a free elite program, with highly qualified coaches that have a playing philosophy and have an individual development plan for every single player.” In the U.S., there simply aren’t enough coaches with any of that. Many currently turn to YouTube and “try to find the best drill,” according to Chris Bentley, U.S. Youth Soccer’s director of education. U.S. Soccer and its members must arm them with better knowledge and resources.

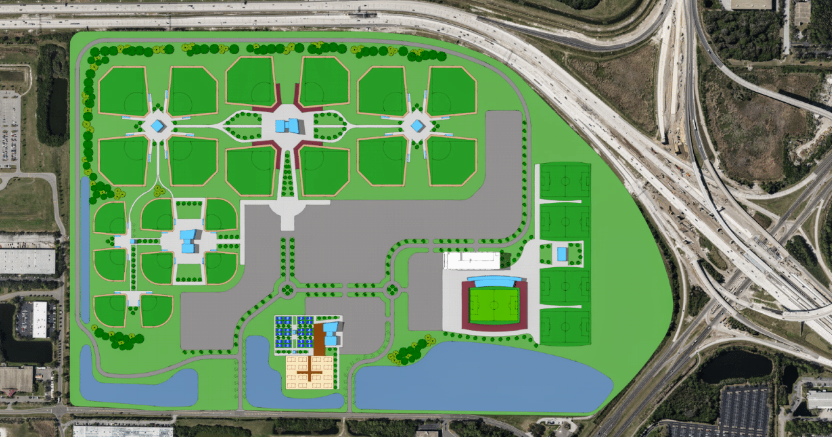

Crocker dreams of having a USSF coaching education hub in each of the 50 states. He knows, of course, that this is an “absolutely unbelievable gigantic project,” one that would require many millions of dollars and could take decades to stand up.

“But,” he continues, “it’s bloody exciting. The reason why I’m here is, I’m excited by these types of huge projects.”

‘A presentation and a document is not a plan’

At many stops on the roadshow, Crocker’s rhetoric has galvanized coaches and administrators. But it has been almost a year since he first outlined “the U.S. Way,” and many are still wondering: What, exactly, is it? How will it come to fruition?

“A presentation and a document,” says Mike Cullina, the CEO of U.S. Club Soccer and a U.S. Soccer board member, “is not a plan.”

Earnie Stewart, Crocker’s predecessor, also had a presentation. Claudio Reyna, U.S. Soccer’s youth technical director in the early 2010s, had a 123-page document. “Everybody,” Cullina says of Reyna’s curriculum, “bought it hook, line and sinker … and then it just disappeared.” Some have wondered skeptically: Is “the U.S. Way” just a well-branded repeat?

“Words on paper is lovely,” Cullina says. “But unless you can operationalize it, and unless you can get the buy-in necessary, it really isn’t going to have any impact.”

What he and others stress, though, is that U.S. Soccer has in fact changed. Crocker’s sporting department and a new soccer growth department are “doing a tremendous amount of work, building relationships” across the landscape, Cullina says.

“The change is dramatic,” Bentley says. “They have people involved, that are full-time employed, that are working directly with their members.”

“I’ve never seen the type of energy and activity that U.S. Soccer has brought to us — the time, the resources,” U.S. Youth Soccer CEO Tom Condone agrees.

Added United Soccer League president Paul McDonough: “This group has been very, very proactive in communication and collaboration.”

Tangibly, thus far, they’ve begun to coordinate a “unified youth calendar” with leagues like MLS Next. They are working on digital platforms. They are reaching out, building trust.

And they are refining what Crocker calls “a really robust plan,” but he acknowledges: “Being able to turn that plan into something that resembles some type of reality, and get it working, and fund it, I think is an astronomical ask.”

Paul Tenorio contributed reporting to this story.

(Top photo: Sandy Huffaker for The Washington Post/Getty Images)