Every year, sixty million kids in America engage in organized sports. Over 26% of these young athletes “specialize” in one sport before they hit puberty, which involves rigorous, year-round training in that particular sport. Focusing on a single sport at such a young age can jeopardize children’s overall growth, health, and passion for sports — […]

Every year, sixty million kids in America engage in organized sports. Over 26% of these young athletes “specialize” in one sport before they hit puberty, which involves rigorous, year-round training in that particular sport.

Focusing on a single sport at such a young age can jeopardize children’s overall growth, health, and passion for sports — whatever sport that might be.

As a former Division I collegiate athlete, I understand why coaches and parents think that early sports specialization leads to success. Mastering any skill demands years of dedication. However, this perception is flawed, and the repercussions for the developing child can be severe.

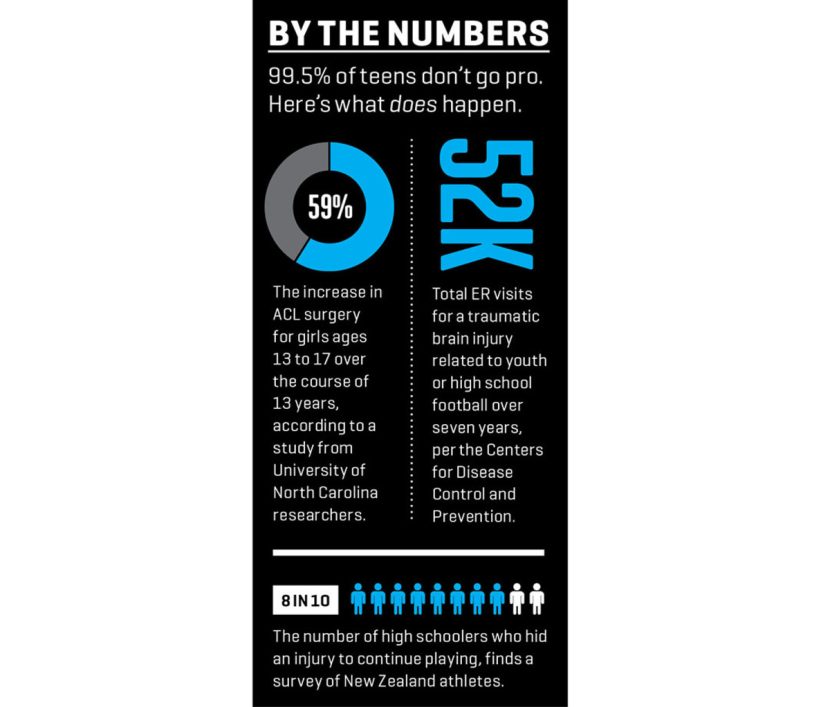

Kids who dedicate themselves to one sport before the age of 12 are 70% to 93% more likely to incur injuries compared to their peers who play multiple sports. Early specialization imposes significant stress on their developing bodies. It can strain particular muscles, ligaments, and joints that aren’t physically prepared for such demands, resulting in serious long-lasting injuries. Overuse accounts for half of injuries in youth sports, primarily due to repeated motions in just one sport.

Crucially, early specialization does not guarantee long-term success. The bedrock of sustained sports excellence is athleticism: agility, balance, coordination, speed, stamina, and strength. Engaging in various sports enhances athleticism. A narrow focus on one sport before puberty develops the player — not the athlete.

Claire Carson, a 22-year-old national champion in rowing, recently highlighted the dangers of early specialization. She recounted how years of excessive training left her “stuck with a broken back” — requiring disc replacement surgery — four years after completing high school. As a sports medicine physician, I have encountered countless athletes like Claire. The injuries, the heartbreak, and the disconnect from sports and family are haunting narratives that should not have to exist.

Burnout is another issue. Athletes who concentrate on one sport too early are at a greater risk of experiencing both emotional and physical fatigue, as well as a reduced sense of enjoyment.

Perhaps the most regrettable aspect of early specialization is its lack of necessity. I was a multi-sport athlete. Participating in various sports did not hinder my success in tennis. I’m far from unique — around 90% of NCAA athletes engaged in multiple sports during their formative years.

As the president of the U.S. Tennis Association, I hold a deep love for tennis. Each shot is unique, which enables developing minds to enhance their executive function and offers a way for young athletes to adapt, manage their emotions, and bounce back resiliently after every serve.

Even though tennis is arguably the healthiest sport in existence, I would never recommend that any child only play tennis. Exploring different sports aids children in acquiring a versatile skill set, fostering athletic growth, and building physical strength.

To cultivate a lifelong passion for sports, it’s vital that the pathway to athletic participation is a low-pressure, enjoyable, and educational environment where children can flourish.

Instead of training kids to become professional athletes from a young age, we should motivate them to engage in a variety of sports, glean lessons from each, and above all — have fun. This approach is the most effective way to nurture not only great athletes but also well-rounded individuals.

— Brian Hainline, MD is the chair of the board and president of the United States Tennis Association and has recently transitioned from the NCAA as their chief medical officer.