No sport has a longer offseason than college football, and it’s nearly inarguable that the sport has as much drama off the field during that eight-month layoff — and during the regular season itself — as it does on Saturdays in the fall.

As The Athletic continues its look back at the last two-plus decades of college football, we examined 25 college football stories whose influences extended beyond the gridiron over the last 25 years, from conference expansion, NCAA power struggles, coaching hires and postseason changes to players whose star power impacted the game in ways the box score did not always measure.

Editor’s note: For more of The Athletic’s look back at the first 25 years of the 2000s in college football, check out our rankings of the top 25 teams, top 25 players, top 25 coaches and top 25 games.

25. Johnny Football

Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel captured the nation’s attention as a thrill-seeking redshirt freshman in 2012, but his celebrity status hit a level rarely seen even for Heisman Trophy winners, thanks in part to a brush with the NCAA. An investigation into allegations that he was paid to sign memorabilia sidetracked his celebratory post-Heisman offseason and led to a half-game suspension. Manziel still became a Heisman finalist in ‘13 but entered the NFL Draft the following spring. His professional fall is a story for a different list.

24. Food deregulation

The NCAA once micromanaged how much food its member institutions could serve on campus. Outside of competitions, schools were allowed to provide one meal per day to athletes. A cracker was considered a snack; a cracker with cream cheese was considered a meal. The rules were so rigid that Oklahoma self-reported violations when three football players ate too much pasta at a graduation buffet in early 2014. The school forced the players to pay $3.83 apiece for the extra food or face ineligibility.

Under increased scrutiny to loosen their grip on the benefits permitted for college athletes, the NCAA lifted all food restrictions on Aug. 1, 2014. The change added significant costs for schools — LSU spent $6.2 million on meals during the 2024 fiscal year — but it restored some common sense to the bottom line.

23. Rise of the recruiting websites

Fans had few one-stop outlets to share their joy, vent their frustration and find nuggets of information on their favorite teams until Rivals debuted in 1998. After Shannon Terry bought the site in 2001, its focus narrowed to recruiting and team message boards, which enabled fans to interact, argue and share content every day of the year.

Scout joined Rivals as a fan fixture in the mid-2000s, before Terry created 247Sports and then On3 that ultimately overtook the earlier fan site models. But the intent remains intact, which is to provide fans with an interactive experience far from the stadium.

22. Bowled over

The bowl system held a much different place in college football at the turn of the century. Outside of the BCS and its four bowls that rotated as title game hosts were 21 other bowl games that held immense power over the selection process. Teams were required to stay on location for a week or more, schools were often saddled with large ticket allotments, including many of the worst seats in the stadium, and programs bid against each other for bowl invitations.

Fast-forward 25 years, and conferences and schools have pushed back on unreasonable trip lengths and ticket requirements. With player opt-outs and the transfer portal lessening the importance of non-College Football Playoff postseason games, many bowls are reinventing themselves as preview exhibitions for next season. Sponsors like Pop-Tarts and Duke’s Mayo have established tongue-in-cheek entertainment products that show a less serious side of the game, which could prolong their relevance in college football’s new era.

21. A 12th game

The number of games in a Football Bowl Subdivision season once fluctuated based on the number of weeks between Labor Day and Thanksgiving weekend. In 2006, the NCAA and its institutions shifted to a consistent 12-game schedule each year, enabling FBS power-conference programs to rake in millions of dollars from an additional home game, leagues to squeeze more from media rights contracts and non-power programs to receive guarantee game payouts that currently range from $500,000 to $2 million or more. The extra game also coincided with leaps in coaching salaries.

It all prompted players to start questioning why they weren’t receiving anything extra despite putting their bodies on the line for another game. From this moment onward, the whispers about fairly compensating athletes ratcheted up in volume.

20. QBs and NIL collide

In September 2024, quarterback Matthew Sluka left UNLV three games into the season while claiming his team’s collective failed to meet its financial obligations. Sluka preserved his redshirt and later signed with James Madison. In April 2025, Tennessee’s Spyre Sports Group rebuffed starting quarterback Nico Iamaleava’s attempt to renegotiate his name, image and likeness deal. Iamaleava sat out the end of spring football practice, entered the transfer portal and landed at UCLA.

Both cases lay the groundwork for future battles between players and management over NIL. Will in-season holdouts become a more regular occurrence? Will the industry move toward increased compensation transparency or binding contracts? Until then, it’s likely a quarterback will one day push even farther than Sluka and Iamaleava.

19. 2003 Big East-ACC war

The ACC and Big East were on equal footing in the early 2000s, but neither conference had the required 12 members to stage a championship game, setting the stage for one to poach from the other. The ACC struck first in 2003, landing Miami and Virginia Tech after about two months of courtship and later adding Boston College as its 12th member.

The Big East sued the ACC and the departing schools, accusing them of conspiracy to defraud the conference. The sides settled in 2005, with the ACC paying $5 million and agreeing to schedule games against Big East teams, and the conferences coexisted for about six years despite the Big East’s waning football influence. Then in 2011, the ACC invited Pittsburgh and Syracuse, which bolstered its ranks and killed the Big East as a football entity.

18. Northwestern’s unionization movement

In 2014, former Northwestern quarterback Kain Colter spearheaded an effort to certify the Wildcats football team as a union and be declared employees, firing a warning shot to the NCAA that athletes were done with complicit silence. The Chicago branch of the National Labor Relations Board ruled that football players are employees, but Northwestern appealed and the full NLRB overturned the decision.

In response to Colter’s efforts, the Big Ten instituted multi-year scholarships and improved its medical insurance. But the NCAA and its membership stubbornly resisted issues raised by Colter regarding practice hours and pay, which led to bigger fights — and losses — for the organization down the road.

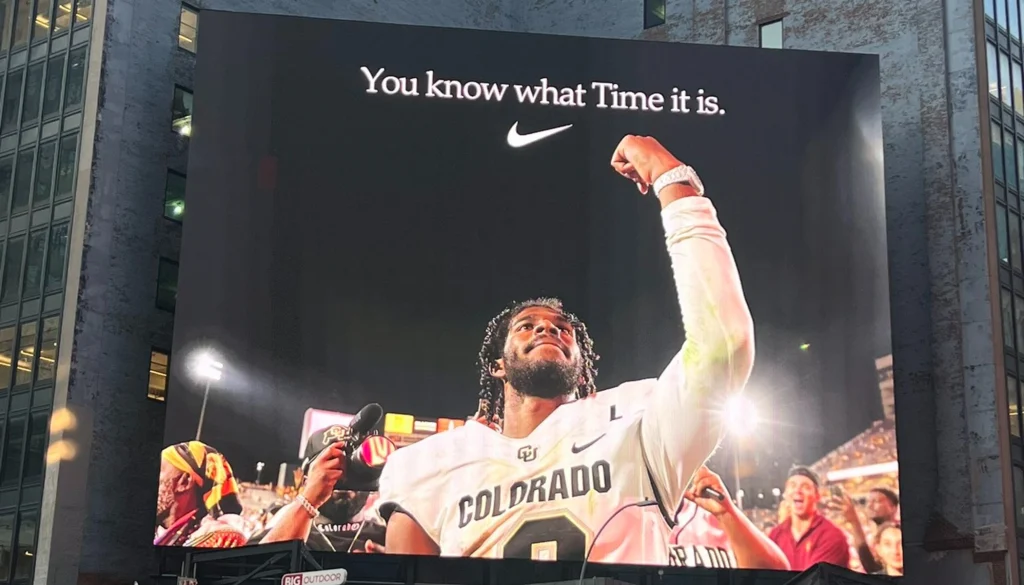

17. Rocky Mountain Prime

Deion Sanders commanded the spotlight during his Hall of Fame playing career, but nothing could prepare college football for his 2023 debut as an FBS head coach in Colorado. Sanders took over a 1-11 squad, flipped the roster and became the sport’s most compelling story as the Buffaloes upset defending national runner-up TCU, then beat rivals Nebraska and Colorado State to start 3-0. Each of Sanders’ first five games drew more than 7.2 million viewers.

With multiple football programs hiring former NFL superstars like Michael Vick (Norfolk State) and Desean Jackson (Delaware State) in the ensuing years, Sanders’ emergence has helped usher in a new level of celebrity to the coaching carousel. His past exploits, charisma and cultural status have helped him connect to potential recruits and fans in a way few coaches can attain. And the five-year contract extension he signed this spring implies he’s not going anywhere.

16. Tebowmania

With his fiery leadership, bruising playing style and public expressions of his Christian faith, Florida quarterback Tim Tebow became one of college football’s most popular and polarizing athletes on Gators teams that won national titles in 2006 and 2008. Between those championships, Tebow was the first sophomore to win the Heisman Trophy. His willingness to take his faith everywhere helped Tebow become one of the sport’s transcendent figures, and his popularity more than 15 years later as a media personality and speaker has extended far beyond his long list of accomplishments on the field.

15. College football’s video game, lost and resurrected

EA Sports’ NCAA Football franchise had players arguing over their ratings and fans leading their favorite teams to championships from the late 1990s through 2014, but NCAA rules prevented players from profiting off of video game characters with suspiciously similar physical attributes to their own. After former UCLA men’s basketball player Ed O’Bannon and other athletes sued the NCAA and EA Sports over the use of his likeness, the game was put on hiatus for a decade and left a void for both fans and athletes.

With players now receiving payment for NIL, NCAA Football returned in 2024 and resumed its role as a cultural phenomenon, bringing fans closer to the sport with realistic graphics and sounds. According to industry tracker Circana, College Football 25 has become the best-selling sports video game of all time in total dollars.

14. Cam Newton

No player was more electrifying over the last 25 years than Auburn quarterback Cam Newton, who lifted the Tigers to the 2010 BCS title without much NFL-bound help around him. But Newton’s lone season of stardom sparked a firestorm when reports surfaced that his father had sought payment for the quarterback’s services while Newton was in junior college.

Lingering questions led Auburn to declare Newton ineligible just days before the SEC Championship Game, then immediately request his reinstatement. The NCAA allowed him to compete during its investigation, which concluded Newton’s father did seek payment but could not find proof the quarterback knew about it. With financial negotiations now an unavoidable part of the player acquisition market, the matter seems trivial in today’s world. But this was the first time the obvious player of the year faced such strong allegations during a Heisman Trophy campaign.

13. Connor Stalions

Michigan staffer Connor Stalions conducted an advanced sign-stealing operation by buying tickets at more than 30 games of future Wolverines opponents over a three-year period and compiling videos of opposing coaches’ signs. Deciphering signals in-game, and modifying your own to avoid detection, had been a cat-and-mouse game common across college football, but the lengths Stalions went to and the fact that the scheme coincided with Michigan’s return to national contention — Stalions even received a game ball after one victory — sent fans and rivals into a frenzy and prompted an NCAA investigation.

The equal parts complex and juvenile scheme, which may have included sideline disguises, brought weekly controversies as Michigan was building a national championship resume. The Wolverines rallied around the scandal and its accompanying suspensions (including three games for coach Jim Harbaugh) on their way to the 2023-24 national championship.

With current coach Sherrone Moore serving a two-game suspension this fall for deleting texts with Stalions sought by investigators, the fallout remains incomplete. However, distrust for Michigan football remains high in Big Ten circles.

12. Reggie Bush’s lost trophy

Reggie Bush’s dazzling runs helped lead the Trojans to a share of the 2003 national title and the undisputed crown in 2004, then won him the Heisman Trophy in 2005. A year later, the NCAA opened an investigation into Bush, who was accused of receiving improper gifts and cash during his USC career. In 2010, the NCAA stripped the Trojans’ 2004 national title, and Bush became the first Heisman winner to forfeit his trophy.

What Bush and his family received was considered improper during his playing days. Today, it’s standard operating procedure. As the rules of college athlete compensation loosened, public pressure mounted on the Heisman Trust to resume honoring the running back. On April 24, 2024, Bush had his trophy returned.

11. The 12-team Playoff

College Football Playoff expansion was a subject of national fascination for years, but it still felt like a surprise in June 2021 when leaders announced the tournament would grow from four teams to 12. But as with most things in college football, even simple processes become complicated.

After the SEC added Texas and Oklahoma later that summer, other leagues put up CFP expansion roadblocks that took years to untangle. All parties eventually agreed to a plan of the six highest-ranked conference champions and the six highest-ranked at-large teams. That template needed to change when the Pac-12 broke apart after the 2023 season.

The full plan for a 12-team CFP was finally approved in February 2024, but the saga has not stopped there. The CFP Board of Managers voted to change the seeding format to a straight ranking after one year and are in ongoing discussions to expand from 12 teams to 14 or even 16 for the 2026 season.

10. Meyer vs. Harbaugh

The Ohio State-Michigan feud matters every day, and two hirings brought red meat to the rivalry and sizzle back to the Big Ten. Urban Meyer took over the Buckeyes in 2012 and promptly called out his fellow Big Ten coaches for their recruiting woes, which was not well received. But Ohio State’s instant success, including a 2014 College Football Playoff title, forced the league to improve quickly or fall further behind.

Tired of floundering against its rival, Michigan hired former quarterback Jim Harbaugh as head coach in 2015. Despite never beating Meyer, Harbaugh brought instant credibility and focus to college football’s winningest program. Like Meyer, Harbaugh won his own national title in 2023.

Their collective success turned the burners up on one of sports’ greatest rivalries, and it remains red hot well after their tenure, courtesy of how Meyer and Harbaugh elevated the Big Ten’s flagship programs.

9. Expansion chaos 2010-11

The zero-sum expansion spat between the ACC and Big East from 2003 to ’05 had little impact on the rest of college football. That was not the case in 2009 when Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany announced his league was exploring expansion on an 18-to-24-month timetable. That forced other leagues to expedite expansion plans, and the Pac-10 launched the first salvo when it pursued six Big 12 schools, including Texas, Texas A&M and Oklahoma.

Colorado became the first Big 12 school to jump to the Pac-10, and Nebraska left for the Big Ten a day later. The remaining schools waited on Texas, which opted to stay in the Big 12. The Pac-10 then added Utah to become a 12-team conference.

But the 10-member Big 12 was far from a happy family. The holdovers allowed Texas to form the Longhorn Network, but the financial and recruiting boost was too much for Texas A&M, so it bolted for the SEC in 2011. That earthquake started another round of aftershocks, and by the time it subsided, Missouri joined Texas A&M in the SEC and the Big 12 added TCU and West Virginia in their stead.

This round of realignment allowed an unvarnished reality to override the platitudes of college athletics: Football is king without exceptions, and brand power trumps on-field excellence.

8. College football’s first playoff

Oklahoma State’s double-overtime loss at Iowa State in November 2011 opened the door for an all-SEC matchup in the BCS Championship Game, clinching a sixth consecutive title for the nation’s premier football conference and roiling the rest of college football.

The Big Ten and Pac-12, which historically had stood in the way of a playoff, finally relented in the face of the SEC’s title wave. Commissioners agreed to the four-team College Football Playoff to begin play in 2014 with a neutral-site national championship game.

Controversy swirled the very first year when Ohio State jumped TCU and Baylor for the final spot, then claimed the first CFP title by upsetting Alabama and Oregon. Eventually, bracket creep became too hot to ignore, and the four-team model was shelved 10 years later. But considering the decades of obstinance in the face of a playoff, it was the single biggest competitive change in college football history.

7. Big Ten Network

Frustrated after a low-ball offer from ESPN in 2004, Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany sat on a Miami beach with Fox executive Larry Jones and sketched on a napkin plans for a new venture: a network dedicated solely to the conference’s sports. The Big Ten Network debuted on Aug. 30, 2007, and once it received full distribution, it became a reliable source of cash and exposure. The league initially owned 51 percent of the network but now owns just 39 percent after selling equity shares to Fox.

The joint venture led to Fox taking a larger stake in college athletics. The network began airing the Big Ten Championship Game in 2011 and picked up the Big Ten’s first-tier rights in 2017.

BTN’s success also spawned similar successful conference networks for the SEC and ACC — which are owned and operated by ESPN, ironically — as well as ill-fated channels like the Longhorn Network and Pac-12 Network.

6. 2020

The first American pandemic in a century had far more pressing consequences than disruption to the sports calendar, but COVID-19’s impact on college athletics was profound. With little guidance from public officials or the NCAA, the conferences were left to decide whether or not they’d play football as the 2020 season approached. After a heated debate, the Big Ten voted 11-3 to shut down football on Aug. 11, and the Pac-12 followed the same day. The SEC, ACC and Big 12 chose to play. After intense public pressure, the Big Ten changed course in mid-September and returned to action in late October, while the Pac-12 started play in November.

The result was an uneven season with no fans at Big Ten and Pac-12 stadiums and limited attendance elsewhere. Several bowl games were canceled, and the Rose Bowl moved to Arlington, Texas. Alabama dominated the season and claimed the national title over Ohio State, which played just eight games. Nearly every athletic department lost millions of dollars, and some are on multi-year repayment plans, are replenishing their reserves that were emptied that year or are still otherwise digging out of the hole those months without games created.

5. Alabama hires Nick Saban

Mal Moore would not take no for an answer. The former Alabama athletic director pestered Nick Saban repeatedly following the Miami Dolphins coach’s second season. Despite multiple denials, Saban relented and turned Alabama into the sport’s signature program.

Hired in 2007, Saban became the college football’s greatest coach of this generation and perhaps of all time. In 17 seasons, Saban won 206 games, nine SEC titles and six national championships. He propelled the SEC into the sport’s dominant conference and forced rivals to improve their staffs to catch up. But his impact stretches beyond his individual leadership qualities.

His coaching tree includes national champions (Kirby Smart, Jimbo Fisher), hall-of-famer Mark Dantonio, CFP semifinalist Steve Sarkisian and dozens of other SEC, FBS and NFL head coaches. Saban has become the authoritative voice for the sport, from his role on ESPN’s “College GameDay” to discussions with President Donald Trump on the future of college football.

4. Expansion and “The Alliance”

The most impactful expansion cycle in college sports history took place in 2021-22, just as the industry reemerged from the pandemic. After Oklahoma and Texas’ shocking plan to leave for the SEC went public, the Big Ten, Pac-12 and ACC formed “The Alliance,” which sought to protect their interests in the face of expansionist SEC aggression. But it was a short-lived, non-binding arrangement. On June 30, 2022, the Big Ten figuratively torched The Alliance and significantly wounded the Pac-12 by luring away USC and UCLA.

Before this expansion, the Big Ten and SEC long were considered first among equals. By taking the major brands from the Pac-12 and Big 12, the leagues rocked an uneasy competitive balance among the five power conferences and set them apart as the sport’s undisputed heavyweights.

3. The Pac-12’s demise

Long known as “The Conference of Champions,” the Pac-12 (previously the Pac-10 and Pac-8) enjoyed a proud tradition as a model academic-athletic conference. But financially it had fallen well behind its long-time partner — the Big Ten — and other power conferences. The league failed to secure distribution of its Pac-12 Network, and inept leadership turned a problem into a crisis.

A cascading departure of members followed USC and UCLA’s jump to the Big Ten, including Washington and Oregon (Big Ten), Arizona, Arizona State, Utah and Colorado (Big 12) and Stanford and California (ACC). Oregon State and Washington State remained as the Pac-12’s only members during the 2024 football season. The duo have mostly reconstituted the Pac-12, grabbing Boise State, Colorado State, San Diego State, Fresno State and Utah State from the Mountain West for 2026. But it is not the same, not even close.

2. Wide open transfers

A decade ago, if athletes wanted to transfer and compete for another institution, they had to sit out for a year. Schools often restricted where athletes could attend on scholarship, and conferences also had rigid rules within their leagues. As rules relaxed, the transfer portal’s arrival in 2018 compelled schools to enter transferring athletes into a database within two days, and players are now eligible to play right away without restriction.

Thousands of athletes hit the transfer portal each year, which has reshaped each sport and remade championship programs in immeasurable ways. Freedom of movement has double-edged pluses and minuses for both coaches and players. Teams get an offseason opportunity for instant improvement, but the fear of losing talent is equally pervasive. Likewise, players have more power to leverage their talent than ever before, but they run the risk of making a wrong move that torpedoes their career.

New coaches often face massive personnel exits, but they also can select players who fit their program more easily than at any time in history. Buoyed by 29 new players through the portal in 2024, Indiana set the program’s wins record (11). Cross-state rival Purdue, conversely, has lost 87 players in the portal the last two seasons.

1. ‘The NCAA is not above the law’

For generations, college athletes signed an annual student-athlete statement that forfeited their rights to earn money based on their name, image and likeness (NIL). No matter how much revenue the NCAA and its member institutions gained from television contracts, the entities stood firm on their bedrock principle of amateurism. It was the barrier the NCAA reinforced at all costs, and it ultimately cost the organization and its member schools billions of dollars.

Lawsuits and law changes punched holes in the NCAA’s definition of amateur athletics, but the status quo was shattered when the United States Supreme Court’s opinion in Alston v. NCAA was delivered on June 21, 2021.

The court ruled 9-0 that the NCAA could not cap “education-related” financial benefits that athletes received from institutions. The landmark decision, though limited in scope, offered signals for how the Supreme Court would rule against the NCAA in other cases regarding players’ ability to make money.

“Nowhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in a scathing opinion. “And under ordinary principles of antitrust law, it is not evident why college sports should be any different.

“The NCAA is not above the law.”

The House v. NCAA settlement, which received formal approval late last week, permits athletic departments to pay athletes directly while providing billions of dollars to former athletes who were prevented from earning revenue while in college. The ability for athletes to generate income at the height of their marketability is not only the most important development of college sports’ last 25 years, it’s the greatest reversal in American amateur sports history.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Kevin C. Cox, Carmen Mandato, Christian Petersen / Getty Images, iStock)

0

Stephen A. responds to LeBron’s NBA coverage criticism | First Take

Stephen A. responds to LeBron’s NBA coverage criticism | First Take