Technology

ASX 200 ends slightly higher; Myer and uranium miners jump — Capital Brief

The news: Australian shares ended the day higher after US markets saw mixed trading overnight as a proposed tax-cut bill passed the US House of Representative and bond yields stabilised.

The benchmark ASX 200 rose 0.15% to 8,360.9, with six of the 11 sectors finishing in the green.

Biggest movers:

- Utilities (-0.97%) – The sector posted the biggest losses, led by Origin Energy (-1.07%), which was dragged down by news that its share of half-year EBITDA from the Australia Pacific LNG joint venture will be $55 million lower. APA Group (-1.45%) and Mercury NZ (-1.75%) shares also fell, although Meridian Energy (+0.95%) and AGL (+0.20%) finished higher.

- Nufarm (-6.08%) – Led losses on the ASX 200 on its third consecutive day of declines after earlier this week reporting a 39.5% drop in half-year statutory profit and a review of its seed technology business.

- Uranium miners – Boss Energy (+12.11%), Deep Yellow (+8.26%), and Paladin Energy (+6.65%) were the top three performers on the ASX 200 following reports that US President Donald Trump will sign an executive order to jumpstart his country’s nuclear energy industry

- Materials (-0.65%) – Declines were led by Fortescue (-2.39%) and Rio Tinto (-1.58%) after both companies announcing executive changes. Fortescue lost CEO Energy Mark Hutchinson and COO Shelley Roberson while Rio Tinto said its CEO Jakob Stausholm will leave later this year. BHP (-0.72%) shares also fell.

Other news:

- Mayne Pharma (+10.8%) – The embattled drug company recovered some of its losses from earlier in the week as Cosette Pharmaceuticals’ $672 million takeover hangs in the balance.

- Myer (+5.41%) – The retailer reported improved sales figures amid tighter margins.

- Bendigo and Adelaide Banks (+0.76%) – Its share price ended higher despite a fall in quarterly cash earnings at Bendigo Bank.

- Challenger (+0.4%) – UBS lifted its 12-month price target from $7.70 to $9.15.

- Silk Logistics Holdings (0%) – The ACCC resumed its probe into multinational logistics giant DP World’s buyout of small-cap ASX-listed logistics firm, with a decision set for 10 July.

- ALS (-0.28%) – Jarden downgraded the stock from ‘neutral’ to ‘underweighted’.

- Catalyst Metals (-4.37%) – Resumed trading after announcing completion of a $150 million discounted institutional placement.

- Australian vintage (-12.79%) – The wine company said it expects to post a 3% decline in sales for FY25.

Technology

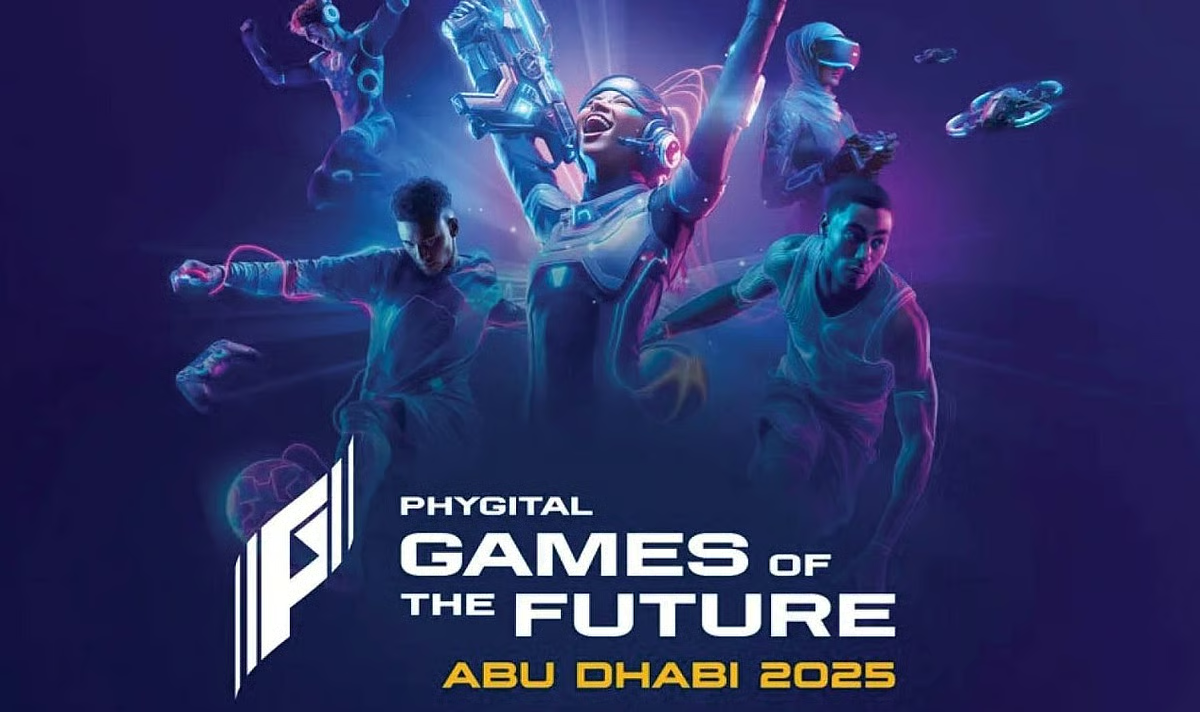

Games of the Future 2025 Offers $5M Prize Pool

“Phygital” sports combine traditional athletic competition with its digital counterpart in a unified format that requires competitors to excel in both dimensions. Teams begin the challenge in the digital round before facing off again in the physical arena, with victory determined by the combined results of both performances.

This model reflects the growing convergence of technology and real-world performance, offering a new and immersive form of sporting competition.

More than 850 athletes from 60 countries will participate, representing clubs, emerging talents, and new faces across 11 phygital sports disciplines.

Faisal Al Bannai, Adviser to the UAE President for Strategic Research and Advanced Technology Affairs and Secretary-General of the Advanced Technology Research Council, said:

“Digital sport is not merely a new format; it embodies the mindset of a new generation.

Bridging physical excellence and digital mastery

Abu Dhabi is proud to host this edition of the Games of the Future 2025, providing an environment that brings together physical excellence and digital mastery. Our goal is to empower youth, accelerate innovation, and build communities around the technologies that will shape the future.”

The 2025 edition comes with strong global momentum, bringing together elite athletes from across the phygital sports ecosystem—competitors who demonstrate exceptional physical performance alongside advanced digital skills.

The event will feature professional athletes, esports stars, and rising phygital talents, promising outstanding competitions that showcase the best of both the physical and digital worlds. The championship reflects the rapid transformation of sport in an increasingly interconnected world, positioning the 2025 edition as a pivotal milestone in the global evolution of this growing sector.

Abu Dhabi prepares to deliver an exceptional edition

The draw has determined the opening group-stage matchups across the various disciplines, setting the stage for the first competitive narratives that audiences will follow. As the event progresses, full competitive pathways will unfold, with clubs vying for qualification and top positions in the finals, which will feature a total prize pool of USD 5 million.

In parallel with the tournament, Abu Dhabi will host the Phygital Sports Summit on 17 December 2025. The summit will serve as an intellectual platform bringing together global experts, athletes, innovators, and decision-makers to discuss the evolution of hybrid sports. Its comprehensive program includes keynote addresses, panel sessions, and in-depth discussions on the intersection of sport and technology, human–AI integration, the future of youth engagement, athlete health in hybrid environments, and the sustainable legacy of phygital sports.

Summit sessions will be moderated by Amy Jane Gillingham, Mohamed Al Hosani, and Sabine Sassen, with participation from senior representatives of Phygital International, partners of the Games of the Future, and leading global figures shaping both the digital and physical sports movements.

Distinguished guests expected to attend include H.E. Dr. Ahmad Belhoul Al Falasi, UAE Minister of Sports, and a high-level international delegation featuring H.E. Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan; H.E. Rawan bint Najeeb Tawfiqi, Minister of Youth Affairs of the Kingdom of Bahrain; Sheikha Deena bint Rashid Al Khalifa, Adviser for Planning and Development at Bahrain’s Ministry of Youth Affairs; and Dr. Osman Aşkın Bak, Minister of Youth and Sports of the Republic of Türkiye.

Sport of the next generation

Technology

The evolution of entertainment technology and its business impact – EUbusiness.com

Entertainment has always played a vital role in society, and the ways we access and enjoy it have changed drastically over time. Today, as online platforms, streaming services, and digital applications gain traction, businesses are rethinking their strategies in this evolving landscape.

Innovations in entertainment technology touch everything from live sports to gaming and betting, as seen at bet777, demonstrating how rapidly shifting trends impact the industry as a whole.

From analog to digital: the transformation of entertainment

The transition from analog to digital technology marks one of the most significant changes in entertainment history. In the past, physical media such as vinyl records, VHS tapes, and CDs were the norm. With the rise of digital formats, accessibility and distribution underwent a revolution. Digital streaming made it possible for consumers to access content instantly, eliminating the limitations of geography and physical storage. This convenience not only changed how audiences consume media but also how creators and companies distribute and monetize their content.

As digital solutions expanded, new forms of entertainment began to emerge. Video games, interactive apps, and online casinos grew in popularity, shifting the focus from passive viewing to active participation. The proliferation of high-speed internet and smartphones further fueled this transformation, enabling entertainment anywhere, anytime. Companies operating in this environment had to adapt quickly to user expectations of on-demand, personalized experiences. This ongoing evolution continues to blur the line between creators, distributors, and consumers, changing the entire value chain.

Streaming services and the shift in business models

The introduction of video and music streaming platforms led to fundamental changes in business models across the sector. Subscription services replaced one-time purchases, shifting the focus to long-term customer retention and recurring revenue streams. This not only increased competition among platforms but also gave rise to exclusive content and original productions as key differentiators. The bargaining power shifted to content creators and platforms able to attract large subscriber bases, while traditional broadcasters and physical retailers had to reinvent or risk becoming obsolete.

This transition has also extended to other segments such as live sports, eSports, and iGaming. Businesses are investing in digital infrastructure and user experience, offering everything from artificial intelligence-driven recommendations to interactive live events. The ability to collect and analyze user data allows companies to tailor offerings directly to their audiences, driving engagement and loyalty. Simultaneously, regulatory challenges and data security concerns have emerged, demanding new approaches to compliance and consumer protection in digital entertainment.

Immersive technology and the business of innovation

The latest chapter in entertainment technology is defined by immersive experiences such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and advanced streaming features. As these technologies find mainstream adoption, businesses are leveraging them to create new ways to engage users. For example, VR concerts, AR-enhanced sports statistics, and immersive gaming environments offer fresh revenue opportunities and deepen the user’s connection with content.

To stay competitive, entertainment companies must constantly invest in innovation and understand emerging trends. Cloud gaming and interactive betting platforms exemplify how technology influences entertainment choices and opens up lucrative business channels. The integration of social features, mobile-first strategies, and cross-platform compatibility are now prerequisites for success. As the landscape continues to evolve, keeping pace with technology and user preferences will be crucial for organizations aiming to thrive in the future of entertainment.

Technology

How Light & Wonder sets the bar with gaming innovation

Kennedy Ntire, Gaming Manager at the Grand Palm Casino, has worked in iGaming for over 15 years so has a strong understanding of what makes players keep coming back for more.

In the video above, he explains why Light and Wonder are the leader of the pack in iGaming innovation and have a unique way of entertaining and captivating both new and experienced players.

Technology

Global Esports Market Size Forecast to USD 20.8 Billion by 2035

Global Esports Market Size Outlook 2035

Global Esports Market Size Outlook 2035

The global Esports market was valued at US$ 2.6 billion in 2024. It is projected to grow at a CAGR of 20.9% from 2025 to 2035, reaching US$ 20.8 billion by 2035. This rapid growth is driven by the surging popularity of competitive gaming, increasing digital connectivity, corporate sponsorships, and expanding live streaming platforms worldwide.

👉 Get your sample market research report copy today@ https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=S&rep_id=54564

Market Overview

Esports refers to competitive gaming at professional levels, where players compete individually or in teams in popular games like League of Legends, Dota 2, Fortnite, Call of Duty, and Overwatch. The market spans across tournaments, leagues, streaming platforms, sponsorships, advertising, and merchandise sales.

Factors contributing to market expansion include:

• Rising internet penetration and smartphone adoption, especially in Asia-Pacific

• Increased viewership via streaming platforms like Twitch, YouTube Gaming, and Facebook Gaming

• Growing corporate investments and sponsorships

• Expansion of Esports tournaments, leagues, and collegiate competitions

• Enhanced engagement through virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) gaming experiences

North America and Europe are leading markets due to mature gaming ecosystems, while Asia-Pacific is the fastest-growing region driven by a huge gamer population and strong tournament culture.

Key Market Growth Drivers

1. Rising Popularity of Competitive Gaming

Competitive gaming is attracting millions of fans globally, creating a robust ecosystem for tournaments, streaming, and merchandise sales.

2. Growth of Digital Streaming Platforms

Platforms like Twitch, YouTube Gaming, and Trovo are expanding the reach of Esports, enabling real-time engagement and monetization through subscriptions, ads, and donations.

3. Corporate Sponsorships and Advertising

Brands are increasingly investing in Esports teams, tournaments, and influencer marketing, enhancing revenue opportunities and market growth.

4. Technological Advancements

• VR/AR integration for immersive experiences

• Advanced graphics, AI, and game engines enhancing competitive gameplay

• Cloud gaming enabling accessibility without high-end hardware

5. Expanding Professional Leagues and Tournaments

Major tournaments like The International (Dota 2), League of Legends World Championship, and Fortnite World Cup are boosting Esports viewership and attracting global sponsorship.

Analysis of Key Players – Key Strategies

Leading Esports companies focus on technology innovation, strategic partnerships, player acquisition, and global expansion.

1. Player and Team Management

• Investment in professional teams, player training, and coaching

• Acquisition of top-tier players to enhance competitive performance

2. Strategic Partnerships and Sponsorships

• Collaboration with gaming hardware, software, and media companies

• Partnerships with brands for event sponsorships and advertising campaigns

3. Platform Expansion

• Enhancing streaming platforms with interactive features, chat, and monetization options

• Developing mobile apps and cloud-based gaming services

4. Regional Growth

• Expansion into Asia-Pacific and Latin America to capitalize on large gamer populations

• Increasing tournaments in emerging markets to boost fan engagement

Analysis of Key Players in the Esports Market

Leading companies in the global esports market are investing in technological innovations, strategic partnerships, and product diversification to strengthen their market presence and stay ahead in the rapidly evolving competitive gaming industry. Their initiatives aim to enhance gaming experiences, improve precision in competitive play, and expand audience engagement globally.

Key players in the esports market include

• Bandai Namco Entertainment

• Valve Corporation

• PGL

• Overwatch League

• NVIDIA

• Microsoft

• Faceit

• Tencent

• Riot Games

• Epic Games

• Sony Interactive Entertainment

• Take Two Interactive

• Activision Blizzard

• Electronic Arts

• Other Prominent Players.

These companies are profiled in the esports market research report based on company overview, financial performance, business strategies, product portfolio, business segments, and recent developments.

👉 Discuss Implications for Your Industry Request Sample Research Report PDF@ https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=S&rep_id=54564

Key Developments in the Esports Market

• April 2025: Nintendo showcased its esports initiatives during the Nintendo Switch 2 Direct event, introducing new IPs and enhancing Splatoon with esports features such as improved matchmaking and live streaming integration. These efforts aim to strengthen Nintendo’s position in the competitive gaming market through strategic partnerships and global audience engagement.

• March 2025: Gameloft launched a new mobile esports platform for Asphalt 9: Legends, focusing on community-driven tournaments and competitive play. The platform features regular in-app events, live streaming, and player rewards, designed to expand the mobile esports ecosystem and attract a larger audience.

Market Challenges & Opportunities

Challenges

1. High Competition and Saturation

The rapid growth of gaming content and tournaments increases competition for viewership and sponsorships.

2. Regulatory and Legal Issues

Issues like laws, online content regulations, and copyright concerns can affect market expansion.

3. Monetization Challenges

Smaller tournaments and emerging platforms may struggle with sustainable revenue generation.

4. Hardware and Connectivity Requirements

High-performance gaming requires advanced hardware and stable internet, limiting access in some regions.

Opportunities

1. Mobile Esports Expansion

Mobile gaming is driving Esports adoption in Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and the Middle East, creating new revenue streams.

2. Integration of VR/AR

Immersive experiences through VR/AR can attract more viewers and participants.

3. Corporate Sponsorship and Advertising

Expanding partnerships with non-endemic brands in fashion, automotive, and consumer goods sectors.

4. Collegiate and Amateur Esports

Development of school and college leagues can create future professionals and increase fanbase.

Investment Landscape and ROI Outlook

The Esports market offers high growth potential and attractive ROI due to its rapid adoption, global fanbase, and multi-stream revenue model.

Investment Strengths

• Expanding fanbase across platforms, regions, and age groups

• Diverse revenue streams from sponsorships, media rights, merchandising, and ticket sales

• Emerging opportunities in mobile Esports, VR/AR integration, and collegiate leagues

• Supportive infrastructure and increasing internet penetration worldwide

ROI Outlook

With a CAGR of 20.9% through 2035, investments in tournaments, streaming platforms, team ownership, and gaming technology are expected to yield high returns. Early entry into emerging markets and mobile Esports offers a competitive advantage.

Market Segmentations

By Game Genre

• MOBA (Multiplayer Online Battle Arena)

• FPS (First-Person Shooter)

• Battle Royale

• Sports Simulation

• Fighting and Others

By Platform

• PC

• Console

• Mobile

• Cloud Gaming

By Revenue Source

• Sponsorship and Advertising

• Media Rights

• Merchandising and Ticketing

• Streaming Platforms

• Publisher Fees

By Region

• North America

• Europe

• Asia-Pacific

• Latin America

• Middle East & Africa

👉 To buy this comprehensive market research report, click here to inquire@ https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/checkout.php?rep_id=54564<ype=S

Why Buy This Report?

✔ Detailed market forecast to 2035

✔ Comprehensive analysis of growth drivers, challenges, and opportunities

✔ Competitive landscape and key player strategies

✔ Segmentation by game genre, platform, revenue source, and region

✔ Insights into emerging trends such as mobile Esports, VR/AR, and collegiate leagues

✔ Strategic recommendations for investors, developers, and brands

FAQs

1. What is the projected Esports market size by 2035?

It is expected to reach US$ 20.8 billion by 2035.

2. What is the CAGR from 2025-2035?

The market is projected to grow at a CAGR of 20.9%.

3. Which region dominates the Esports market?

Asia-Pacific is emerging as the fastest-growing region due to high gamer population and mobile gaming adoption.

4. What are the main revenue sources?

Sponsorships, advertising, media rights, streaming subscriptions, merchandising, and ticket sales.

5. What are key market trends?

Growth in mobile Esports, VR/AR integration, streaming platforms, and collegiate leagues are shaping market trends.

More Trending Research Reports-

• Enterprise Connectivity and Networking Market – https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/enterprise-connectivity-and-networking-market.html

• A2P SMS Market – https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/global-a2p-sms-market.html

About Us Transparency Market Research

Transparency Market Research, a global market research company registered at Wilmington, Delaware, United States, provides custom research and consulting services. The firm scrutinizes factors shaping the dynamics of demand in various markets. The insights and perspectives on the markets evaluate opportunities in various segments. The opportunities in the segments based on source, application, demographics, sales channel, and end-use are analysed, which will determine growth in the markets over the next decade.

Our exclusive blend of quantitative forecasting and trends analysis provides forward-looking insights for thousands of decision-makers, made possible by experienced teams of Analysts, Researchers, and Consultants. The proprietary data sources and various tools & techniques we use always reflect the latest trends and information. With a broad research and analysis capability, Transparency Market Research employs rigorous primary and secondary research techniques in all of its business reports.

Contact Us

Transparency Market Research Inc.

CORPORATE HEADQUARTER DOWNTOWN,

1000 N. West Street,

Suite 1200, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 USA

Tel: +1-518-618-1030

USA – Canada Toll Free: 866-552-3453

Website: https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com

Blog: https://tmrblog.com

Email: sales@transparencymarketresearch.com

This release was published on openPR.

Technology

How eSports and Gaming Platforms Are Shaping Interactive Digital Communities

The gaming and eSports industries have grown far beyond simple entertainment. Today, they represent a complex ecosystem where competition, social engagement, and technology intersect. Fans don’t just play—they spectate, strategize, and participate in online communities that feel immersive and dynamic.

Competitive gaming has influenced not only game design but also how digital platforms structure engagement. Leaderboards, progression systems, and interactive features once reserved for video games now appear across entertainment, social, and even educational platforms. This approach keeps users invested and encourages continuous interaction.

Platforms like spacehills.de are perfect examples of this trend. While focusing on gaming and eSports experiences, the platform integrates community-driven features, gamified interactions, and real-time engagement tools that resonate with pop-culture and tech-savvy audiences. Users find themselves drawn into a system that feels familiar yet innovative, combining the thrill of competition with interactive platform design.

The Mechanics Behind Engagement

Gamification remains one of the strongest drivers of user engagement in modern digital spaces. Borrowed from video games, these mechanics transform standard interactions into meaningful experiences. Users enjoy clear goals, rewards for skill or participation, and tangible progress that mirrors in-game achievements.

Core Gamification Elements

- Achievement tracking – recognizing user milestones

- Progression bars and levels – visually representing growth

- Daily or weekly challenges – encouraging consistent engagement

- Reward systems – motivating repeated interactions

By leveraging these mechanics, platforms create a sense of investment and personal growth, even outside traditional gaming contexts.

eSports Influence on Platform Design

The structure and intensity of eSports competitions have heavily influenced digital platform design. Just as tournaments require skill, strategy, and adaptability, interactive platforms aim to provide layered experiences that challenge and reward users in meaningful ways.

Key Design Features Inspired by eSports

- Real-time updates – keeping users informed and engaged

- Interactive dashboards – allowing immediate response and action

- Community integration – fostering connection among players

- Performance metrics – tracking progress and achievements

These elements ensure that users feel involved and motivated, replicating the engagement loop found in competitive gaming.

Social Interaction and Community Building

A defining feature of modern gaming and eSports culture is community. Whether it’s clan systems, guilds, or Discord channels, shared experiences amplify engagement. Digital platforms that integrate social features replicate this environment, creating a sense of belonging and collaboration.

Community-Driven Features

- Forums and chat systems for discussion and collaboration

- Leaderboards to encourage friendly competition

- Collaborative challenges or events

- Transparent systems that reward fair play

Strong communities increase retention and make platforms more attractive to both new and experienced users.

Strategy, Skill, and Decision-Making

Gaming and eSports emphasize strategy and skill, which naturally translate into interactive platforms. Users are drawn to experiences that reward decision-making, resource management, and tactical thinking. This dynamic creates depth and keeps users engaged over time.

Strategic Engagement Elements

- Risk versus reward decisions

- Progression-based challenges

- In-game or in-platform resource management

- Analytical decision-making feedback

By incorporating these elements, platforms encourage thoughtful participation rather than passive consumption.

Technology Driving Immersion

Technological advancements have enabled platforms to support high-performance, real-time interaction similar to competitive gaming environments. Cloud computing, low-latency servers, and responsive design ensure that users experience smooth, immersive engagement.

Tech Features Enhancing User Experience

- Mobile-optimized and responsive interfaces

- Low-latency real-time updates

- Secure user accounts and transactions

- Scalable architecture to handle peak traffic

These features make platforms feel modern, reliable, and aligned with user expectations shaped by gaming and eSports experiences.

Personalized Experiences and Adaptive Systems

Modern platforms increasingly rely on data to provide personalized experiences. By monitoring user behavior, preferences, and engagement patterns, platforms can dynamically adapt content, challenges, and rewards to each individual.

Benefits of Personalization

- Tailored challenges and events

- Customized interfaces and dashboards

- Adaptive difficulty and content progression

- Enhanced user satisfaction and retention

This approach mirrors personalized gameplay experiences in video games, where user choices and performance influence outcomes.

The intersection of eSports, gaming, and digital platform design demonstrates how interactive experiences are evolving. Platforms like spacehills.de illustrate how combining community, gamification, and technological innovation creates compelling environments for users, where engagement, strategy, and social interaction coexist seamlessly.

Do You Want to Know More?

Technology

Superbet Group Becomes Super Technologies, Shaping the Future of Digital Entertainment Ecosystems

Our website uses cookies, as almost all websites do, to help provide you with the best experience we can.

Cookies are small text files that are placed on your computer or mobile phone when you browse websites.

Our cookies help us:

– Make our website work as you’d expect

– Remember your settings during and between visits

– Offer you free services/content (thanks to advertising)

– Improve the speed/security of the site

– Allow you to share pages with social networks like Facebook

– Continuously improve our website for you

– Make our marketing more efficient (ultimately helping us to offer the service we do at the price we do)

We do not use cookies to:

– Collect any personally identifiable information (without your express permission)

– Collect any sensitive information (without your express permission)

– Pass personally identifiable data to third parties

– Pay sales commissions

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoRedemption Means First Pro Stock World Championship for Dallas Glenn

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoJo Shimoda Undergoes Back Surgery

-

NIL2 weeks ago

NIL2 weeks agoBowl Projections: ESPN predicts 12-team College Football Playoff bracket, full bowl slate after Week 14

-

Motorsports7 days ago

Motorsports7 days agoSoundGear Named Entitlement Sponsor of Spears CARS Tour Southwest Opener

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoHow this startup (and a KC sports icon) turned young players into card-carrying legends overnight

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoRobert “Bobby” Lewis Hardin, 56

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoPohlman admits ‘there might be some spats’ as he pushes to get Kyle Busch winning again

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Wisconsin volleyball sweeps Minnesota with ease in ranked rivalry win

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoIndiana’s rapid ascent and its impact across college football

-

Motorsports1 week ago

Motorsports1 week agoDonny Schatz finds new home for 2026, inks full-time deal with CJB Motorsports – InForum