NIL

Can Nick Saban and a Texas billionaire fix college sports? What we know about their vision

Dramatic changes in college sports have drawn the attention of the White House, and two prominent men from the world of college football are set to co-chair President Donald Trump’s commission on college athletics—an effort to get the train back on the tracks amid mounting issues in the collegiate model. It’s too early to know […]

Dramatic changes in college sports have drawn the attention of the White House, and two prominent men from the world of college football are set to co-chair President Donald Trump’s commission on college athletics—an effort to get the train back on the tracks amid mounting issues in the collegiate model.

It’s too early to know how former Alabama coach Nick Saban and Texas billionaire businessman Cody Campbell will co-lead the commission and who will be on it. As Texas Senator Ted Cruz’s NIL legislative effort launched in 2023 languishes and administrators still await the House settlement’s final approval, patience has long run thin for substantive change in college athletics. One power conference official told CBS Sports they didn’t need any more college sports insiders in a group like this; rather, they wished for outsiders who can bring fresh ideas and aren’t lifers.

“We don’t need a committee to tell us what’s wrong with college sports, we know that,” the official said. “We need this group to cut through bureaucracy and actually get stuff done.”

Saban and Campbell have shared their positions on several pertinent issues recently, including NIL, the transfer portal, conference realignment, multimedia deals and how they would improve an unwieldy collegiate athletics system.

Both also have relationships with the Trump administration. Saban, who won six national titles at Alabama and retired after the 2023 season, bent Trump’s ear last week to discuss college sports legislation during a graduation ceremony at the University of Alabama. Campbell, the chairman of Texas Tech Board of Regents, hosted Vice President JD Vance at a Fort Worth Luncheon in September during the run-up to the presidential election. He’s connected in the state’s Republican politics and is an appointee of Texas Governor Greg Abbott to the Texas Tech Board of Regents. Campbell has made multiple six-figure donations to Abbott, Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and the Republican national committee.

A former Texas Tech football player who’s made a killing in the energy industry, Campbell has been heavily involved in the NIL space since 2022, when he founded The Matador Club, Tech’s NIL collective. Fueled by the deep pockets of its supporters, the collective helped secure the nation’s No. 2 transfer portal class this spring. Tech’s spend in the December portal alone was close to $10 million, according to sources, and that’s before a spring haul that included Stanford edge David Bailey, who sources say signed for over $2.5 million.

“We should be the most talented team in the Big 12 this year,” Campbell told CBS Sports’ Dennis Dodd two months ago.

Armed with ambition, resources and Patrick Mahomes, Texas Tech forges ahead well-equipped to thrive in new era

Dennis Dodd

Portal gold mine aside, Campbell has remained critical of the business of college sports, penning multiple columns for The Federalist regarding the dangers of conference realignment weakening college sports, and NIL’s adverse effects on Olympic sports and the transfer portal.

“If we completely professionalize college sports, further extract and further concentrate the excess revenue provided by football and men’s basketball, college athletics will disappear for the majority of the Americans who have enjoyed and benefited from it for generations,” Campbell wrote on April 14.

Campbell and Saban have mostly echoed the concerns of conference commissioners and NCAA leadership, while drawing allies in Congress like Cruz, who is reportedly drafting a bill on reforming college sports. Campbell and Saban, however, have also criticized the NCAA.

Let’s look at where Campbell and Saban stand on the pertinent issues in college sports, and how their past might shape their future as co-chairmen of the presidential commission on college sports.

Universal NIL regulations and antitrust protection

Campbell and Saban have been critical of the slow march toward the professionalization of college athletics as players in football and basketball sign multi-million-dollar deals and smaller programs struggle to keep up in the NIL era.

Saban has appeared in Washington, D.C., multiple times to speak to legislators. In May 2024, he appeared alongside Cruz on Capitol Hill to address a committee on the effects of NIL and free agency in college athletics.

“It’s whoever wants to pay the most money, raise the most money, buy the most players is going to have the best opportunity to win,” Saban said at the hearing. “I don’t think that’s the spirit of college athletics.”

The $10 million club: College basketball’s portal recruiting hits unthinkable levels of financial chaos

Matt Norlander

Collegiate leaders have descended on Capitol Hill several times to lobby for legislation to protect the collegiate enterprise from litigation tied to NIL and revenue-sharing. The NCAA spent $450,000 in the first quarter of 2025 to lobby the Republican-controlled Congress, according to Front Office Sports.

Like many NCAA and conference leaders, Campbell has called for antitrust protection from Congress. “There must be a single set of rules and laws to govern college sports across the country – not a patchwork of 34 different state laws, as we have today,” he wrote, in reference to NIL laws, in a column published in April.

The NCAA has lost or settled multiple lawsuits involving student-athletes’ money-earning rights since 2020. The NCAA and five power conferences are also close to settling a $2.8 billion antitrust lawsuit that will also allow schools to share up to $20.5 million in revenue annually with players.

Concerns about financial inequality further dividing college athletics has also been at the forefront of lobbying efforts.

“My only hope is that leadership can emerge and consensus can be found in Washington before it’s too late,” Campbell wrote in April. “There are solutions, and the problems can be solved in a bipartisan manner. It is only a matter of will, engagement, and attention from well-intentioned individuals who wish to perpetuate the legacy and impact of the great American institution of Intercollegiate Athletics for all of its participants – not just for a privileged few.”

A new approach for conferences and media rights

Interestingly, nearly one month before Cruz voiced concerns about college football’s lack of antitrust protection in the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961, Campbell penned a column on the subject’s effect on college football.

Campbell believes college football’s inclusion in the Sports Broadcasting Act could pave the way for multiple conferences to pool their media rights to sell to TV partners, which would “install a media revenue distribution system that would significantly increase total revenue and would promote parity.” He also believes a group deal could reset conferences, allowing for more alignment that make “geographic sense.”

“Because the conferences must compete with each other for media deals, they are incentivized to organize into leagues that span multiple time zones, and cover the full width of the continent,” Campbell wrote. “This has resulted in the loss of traditional rivalries and has ballooned travel expenses and time away from the classroom, especially for the non-revenue sports.”

Cruz criticized the NFL for bending the SBA’s guidelines by encroaching on high school and college football with the recent scheduling of NFL games on Black Friday, a day that has historically been tied to college football. The SBA does not allow the NFL to broadcast games on Friday night or Saturdays from the second weekend in September through the second weekend in December. The NFL recently began scheduling games on Fridays and Saturdays outside those windows, when high school and college football games are still being played late in the season.

“The NFL has tiptoed up to this rule,” Cruz said Tuesday at a Senate Commerce Committee hearing.

Conference equality

The threat of weakened Olympic sports in this new era has been of particular concern for Campbell.

The businessman wrote in March that he is concerned the power conferences may soon worsen things if allowed to wield more power in Washington.

“The top 40 most-viewed college football programs already hog 89.3 percent of TV eyeballs and 95 percent of media cash. Give the Autonomy Four (especially the Big Ten and SEC) a free antitrust hall pass, and they’ll build a super conference, a gilded monopoly that starves everyone else of the revenue needed to provide opportunity to more than 500,000 student athletes per year. Of 134 FBS schools, 90 or more could lose funding for Olympic sports, women’s teams, and even football itself (not to mention the FCS and Division II). Local towns could crumble. Smaller colleges would fade. College sports would shrink from a national treasure to an elite clique, and countless dreams would be crushed.

“This isn’t about left or right; it’s about right and wrong. The NCAA is broken, but handing the keys to a few fat cats is worse. America thrives on competition, not cozy cartels blessed by D.C.”

NIL

UCLA baseball reliant on sophomores in College World Series run

4 MLB prospects to watch during the 2025 Men’s College World Series 4 MLB prospects The Montgomery Advertiser’s Adam Cole and The Southwest Times Record’s Jackson Fuller are watching during the 2025 Men’s College World Series OMAHA, NE ― Don’t tell the teams in the 2025 College World Series that paying transfer portal prospects top […]

4 MLB prospects to watch during the 2025 Men’s College World Series

4 MLB prospects The Montgomery Advertiser’s Adam Cole and The Southwest Times Record’s Jackson Fuller are watching during the 2025 Men’s College World Series

OMAHA, NE ― Don’t tell the teams in the 2025 College World Series that paying transfer portal prospects top dollar in NIL money is necessary to be here.

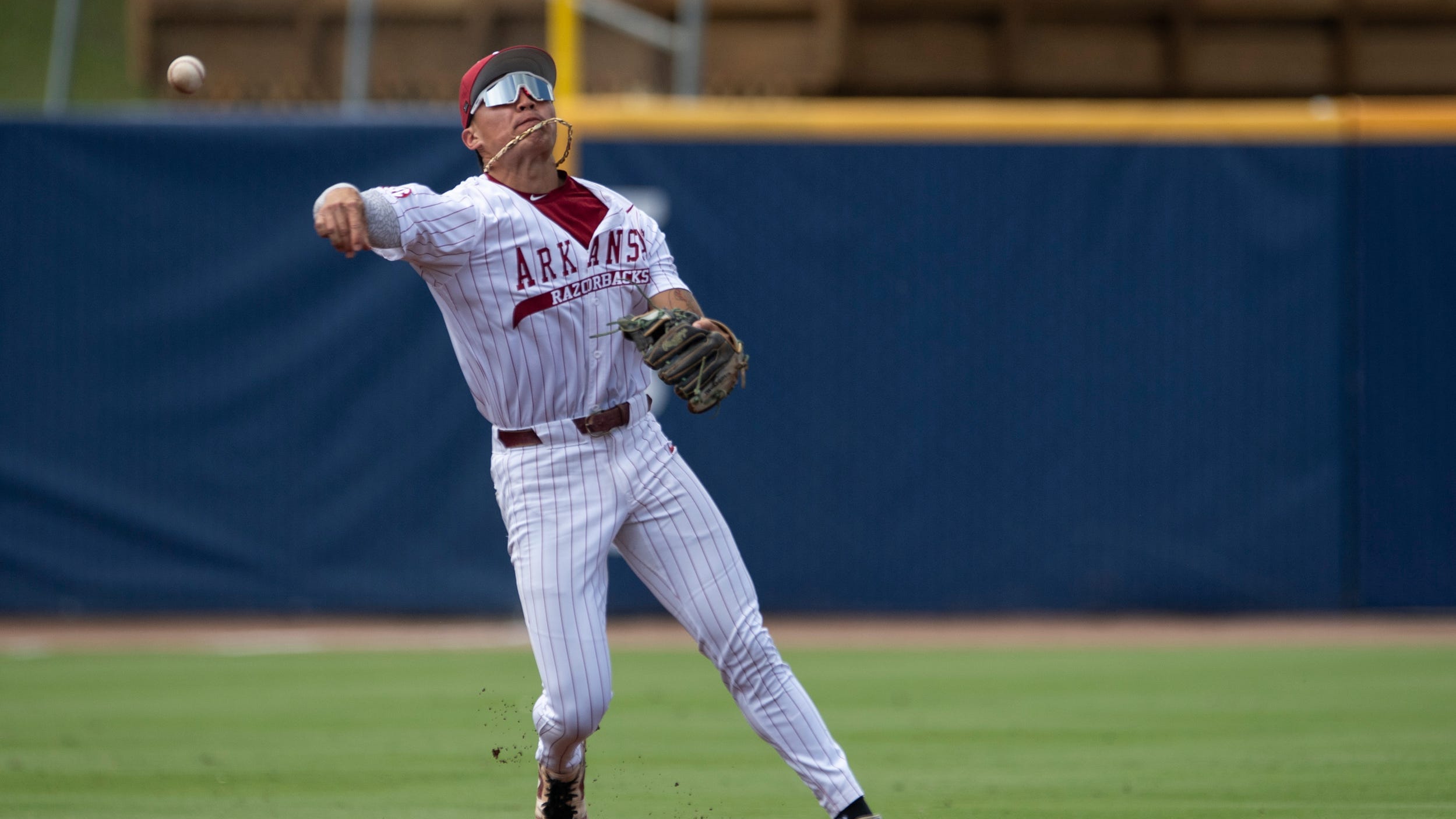

Yes, there are a few of those teams in Omaha, most notably Arkansas and LSU. But the other teams — Coastal Carolina, Arizona, Louisville, UCLA, Murray State and Oregon State — weren’t exactly writing blank checks.

Those teams were built in different ways. Transfers make up the majority of Arkansas’ top contributors, but LSU’s roster has a combination of top-ranked transfers and former blue-chip high-school recruits. Oregon State, Louisville and Coastal Carolina have focused mostly on identifying and developing players out of high school. Arizona and Murray State excelled at finding players out of the junior college ranks.

And then there’s UCLA, which will face off against LSU in a winners bracket game on June 16 (7 p.m. ET, ESPN) at Charles Schwab Field for a spot in the semifinals. The 2013 national champions had fallen on hard times. The Bruins hadn’t been to Omaha since that national title and failed to qualify for a regional altogether in 2023 and 2024. UCLA had the nation’s top-ranked recruiting class in 2023, and those players played a lot as freshmen, but a year ago the strategy didn’t seem to be working out.

But the Bruins stuck with it. Going into the 2024 season, they took just two transfers — pitchers Ian May from Cal and August Souza from Santa Clara. Only one other player on the roster was a transfer: outfielder AJ Salgado, who transferred from Division II Cal State Los Angeles before the 2023 season and has spent the last three seasons with the Bruins.

But in 2025, the blue-chip talent on the roster began to come through. Despite a rough season in 2024, the team’s impending move to the Big Ten and the fact that several UCLA players had transferred to the SEC in past seasons, 14 of the 16-member 2023 recruiting class stayed with the Bruins. The two who did not both went to junior colleges.

The crown jewel of that class was Roch Cholowsky, who hit .308 with eight home runs as a freshman but exploded for .367 and 23 home runs as a sophomore. Cholowsky was named the Big Ten Player of the Year and a Dick Howser Trophy finalist.

Cholowsky isn’t the only one. Seven of UCLA’s nine starters in its College World Series-opening win over Murray State were part of that sophomore class. Dean West and Phoenix Call each had two hits; Roman Martin had two RBIs.

“Really the last couple of years, the last thing you want to be is young in college baseball, college football, college basketball,” Bruins coach John Savage said in UCLA’s pre-Omaha press conference on June 12. “That model used to work. But that model doesn’t work as many freshmen as we had. So, now if they turn into super sophomores, like we have now. Then you wore it last year and now you come back and it’s paid off. But some people don’t have patience.

“But to our credit our kids have stayed together. They believe in one another. They’re really good players. And there’s a lot of future high prospects on our team other than Roch.”

The Tigers, who defeated Arkansas in their opening game, are an example of a perfect transfer portal strategy. They brought in several impact players in the offseason, including pitchers Anthony Eyanson and Zac Cowan, and second baseman Daniel Dickinson. But LSU, too, has plenty of contribution from its own recruits like ace pitcher Kade Anderson, first baseman Jared Jones, outfielder Derek Curiel and reliever Casan Evans.

But in an era in which outsiders increasingly see a roster-building strategy like LSU’s as a necessity to win championships, teams such as UCLA with throwback strategies are looking to buck that trend.

Aria Gerson covers Vanderbilt athletics for The Tennessean. Contact her at agerson@gannett.com or on X @aria_gerson.

NIL

The evolving landscape of college athlete pay

Cat Flood recounted the DM she got from the Pennsylvania Beef Council around two years ago that started her down the road of cashing in on college volleyball stardom. The nonprofit wanted her to promote its mission of “building beef and veal demand with consumers of all ages.” She recorded a series of videos for […]

Cat Flood recounted the DM she got from the Pennsylvania Beef Council around two years ago that started her down the road of cashing in on college volleyball stardom. The nonprofit wanted her to promote its mission of “building beef and veal demand with consumers of all ages.”

She recorded a series of videos for her Instagram, one of which got over a million views. In the post, she invited followers along a day in her life — notably, eating jerky for her first snack, steak for lunch and later on, more jerky. The council paid her $1,000.

Deals like this are commonplace in today’s college athletics landscape, where for four years, athletes have been profiting from use of their name, image and likeness [NIL].

“NIL made us all influencers,” Flood said.

As one of the University of Pittsburgh’s most popular athletes, Flood — who recently graduated — benefited from NIL deals, averaging one or two a month, and saw how their introduction changed the nature of college sports.

And more change is on the horizon with the June 6 approval of a landmark NCAA settlement letting colleges pay their athletes that takes effect July 1. Universities in the former Power Five conferences (recently reduced to four), including Pitt and Penn State, will each have to split $20.5 million annually between players for a decade. The yearly amount will increase incrementally.

While the settlement ushers in more money for athletes, it’s unlikely to be spread evenly, and certain NIL deals will be scrutinized for the first time. Uncertainty about how the millions will be distributed and exactly how the settlement terms will be enforced has rattled college athletes and spurred state lawmakers alike.

PublicSource spoke to several athletes, state representatives and NIL experts about their thoughts on the second big change in compensation in just this decade. Here’s what they had to say.

Antonio Epps, Duquesne University

School division: Division I, outside of Power 4 conferences

Year: Senior

Sport: Football

Recent NIL deal: None

Dream NIL deal: Pizza Hut

Before NIL came into play, Epps said, “there was always talk about how being a college athlete was very similar to working a 9-5, in a sense.”

He was a sophomore when the NCAA allowed athletes to have NIL deals and became a part of Duquesne’s Red and Blue NIL collective. Through this, he’s able to make money from merch and generally feels NIL has been a good thing.

“It can help out a lot of people who didn’t have as much money coming into college,” he said.

Duquesne is one of the schools that can choose to opt into sharing a portion of their athletics department revenue with athletes, but isn’t required to do so.

A university spokesperson confirmed that Duquesne is opting in.

Epps said that although the conversation has been about athletes, they’re being left in the dark when it comes to understanding what impact this will have on them.

“A lot of the conversations that happen, happen around us, but a lot of us are not told the [parameters] of what is being said.”

When the NIL policy first went into effect in 2021, it was expected that money would largely come from endorsement rights opportunities — think brand deals like Flood’s Pennsylvania Beef Council posts. Then collectives emerged, said University of Illinois labor and law professor Michael LeRoy.

Collectives are groups that pool donations to pay athletes for use of their NIL, while facilitating deals for them. While these are usually school-specific, they’re operated independently, though there’s often some level of collaboration with the college.

Once athletes sign contracts with collectives, there’s an expectation that they’ll get paid, but which players are paid and how much is up to the discretion of the collective’s head. Last fall, the founder of Pitt’s collective, Alliance 412, along with the university’s football coach, stopped paying all members of the team, instead compensating only some to incentivize better performance.

The NCAA settlement retains a longstanding ban on compensation solely related to athletic performance or participation. Nonetheless, the NIL system has been called “pay for play,” because it seemingly rewards performance in many cases.

“There’s so much pent-up demand among supporters and the businesses … neither the laws nor the rules have caught up with the market supply of NIL money for athletes,” LeRoy said.

A majority of NIL funds come from collectives, not endorsements, sponsorships or appearances, according to Philadelphia-based NIL agent and attorney Stephen Vanyo. When he’s looking at contracts with collectives for clients, he said a player’s NIL value is being assessed based on what they will bring to a team. This is subjective, but factors include stats and social media following.

None of the athletes PublicSource interviewed disclosed their NIL values. Some of them did not have the figures.

LeRoy, who has researched NIL earnings, said that men outearn women 10:1 in deals, with the most money going to men’s football and basketball players. The settlement is expected to do little to remedy this, opening the doors for lawsuits against schools under Title IX, which requires schools to provide equal financial assistance opportunities to men and women athletes.

With no stipulations on how colleges have to divvy up the $20.5 million, experts have predicted that as much as 70-90% will go to men’s football, men’s basketball and women’s basketball, in that order.

Cat Flood, University of Pittsburgh

School division: Division I, ACC

Year: Graduated in 2025

Sport: Volleyball

Recent NIL deal: Saxbys

Dream NIL deal: World Wildlife Fund or Free People

Last year, Pitt’s volleyball team was ranked third in the country by the NCAA, finishing the 2024-2025 season 33-2.

Flood joined the team in 2020 after one visit to a university volleyball clinic. “I fell in love with it on the spot,” she said.

Recruiting, to her, was all about considering, “Where am I going to have the best four years?” not where she could get the most money in NIL deals. She never joined Alliance 412.

“I didn’t love the idea of NIL, I had seen what it had done to a lot of players,” she said. “They were playing for the money, they were transferring for the money.” She preferred to use NIL to promote local businesses in mutually beneficial, ethical arrangements.

However, after the volleyball team’s continued success, she began to regret not taking NIL more seriously. She saw NIL funds flowing to men’s football and men’s basketball, which she believed was fair due to viewership. But she noted that despite her squad being “the best team at the university … the women’s side was getting nothing.”

With players now getting paid a portion of the revenue that college athletics departments receive, she wants to see women’s volleyball benefit.

“I hope that we bark up some NIL trees.”

In the year it’s taken for the settlement terms to be negotiated and finalized, schools have prepared to start paying athletes. One way was by presenting recruits with NIL contracts that would only become effective after the settlement’s approval.

Alex Guminiski, a Pittsburgh-based NIL agent and attorney, has seen over 20 of these so far — some for Pitt recruits — but due to confidentiality clauses, couldn’t give more details. He stressed, though, that “it’s not pay for play,” but rather “licensing deals.”

“The school is asking the player to grant the school the license to use their NIL in all sorts of media,” Guminiski said.

LeRoy, the professor who obtained similar contracts from schools in the Big Ten and SEC conferences, said players are being asked to give away “an irrevocable right” to their collegiate NIL. These terms aren’t negotiable, he added.

“They are going to be paid for this, and in many cases, paid well. But again, people likely don’t know what they’re signing.”

LeRoy worries about the exploitation of athletes, especially those without an agent. He sees these contracts as a way to sidestep the perennial question of whether college athletes are employees of the schools they play for — another area many experts believe will play out in the courts.

Vanyo called the settlement “another half measure” because of the legal challenges it is likely to ignite. He said the only sustainable solution for stabilizing the industry is to allow athletes to unionize and collectively bargain, as players in professional leagues do. Then, there’d be what he described as a “semblance of fairness.”

“It’s the only thing we’ve seen work in the American sports model,” he said.

Ryan Prather Jr., Robert Morris University

School division: Division I, outside of Power 4 conferences

Year: Junior

Sport: Basketball

Recent NIL deal: C4 Energy

Dream NIL deal: Nike

Ryan Prather Jr. has had a long journey to Pittsburgh. After playing at the University of Akron through his first two years of college, he decided to transfer and commit to RMU in 2024.

“I wanted somewhere I could go and showcase what I could do,” he said.

He changed schools in part to be closer to home and family, but also due to the opportunities he could envision. After transferring, he joined RomoRise, an NIL collective specifically for RMU students, and has taken advantage of the deals presented to him.

As the settlement is sure to prompt changes to deals, Prather said, “It definitely has an effect on anyone who’s trying to play in college … they come in with a certain amount in their head.”

Prather said he understood the benefit of college athletes getting paid to do what they love. “The money helps you out in the long run because if you use up your money and save it up and invest, you can start early rather than waiting until after college for your career to get started.”

The downside: “It’s kind of hard at the same time because no team is going to stick with each other.” With teams changing every year due to players leaving, it can be difficult to produce a cohesive team environment.

“More money doesn’t always mean a better situation.”

The NCAA has been trying to wrangle what it views as an out-of-control stream of money going to athletes via NIL deals over the past few years, in part because athletes are transferring schools at record numbers, which some believe is due to money offered by collectives.

Under the settlement’s rules, third-party NIL deals valued at or above $600 will be reported to a clearinghouse run by consulting firm Deloitte. The goal, LeRoy said, is to regulate the market.

The clearinghouse will determine if deals fall under “pay for play” and evaluate their fair market values. Deals have to be approved before an athlete can receive the funds.

Little is known about the specific criteria needed for compliance, but experts told PublicSource that there isn’t a set fair market value for any NIL deal, and trying to determine one is next to impossible.

Vanyo said fair market value in the industry is simply “what somebody’s willing to pay.”

“In no other industry do we have … a clearinghouse that then says, ‘OK, this is a fair salary,’” he continued.

Some experts describe the clearinghouse as a way to scale back how much some athletes are earning.

“While nobody knows for sure how this is going to come out, the clear implication is that most of the NIL deals, particularly in men’s revenue sports — football and men’s basketball — will not be accepted as fair market value,” LeRoy said. A new College Sports Commission, separate from the NCAA, could then reject such deals.

It’s been reported that Deloitte officials said 70% of past deals from collectives would be rejected under the clearinghouse.

Unsurprisingly, legal challenges by those with rejected deals are expected to follow.

Aurielle Brunner, Chatham University

School division: Division III, Presidents’ Athletic Conference

Year: Graduated in 2025

Sport: Track and field, Soccer, Basketball

Recent NIL deal: P3R, a local event management organization

Dream NIL deal: Nike

Brunner believes college athletes are valued professionals and views the settlement as a “huge step for sports.”

She holds 10 All-American awards for her track and field success. As Chatham University’s most decorated athlete of all time, she quickly stood out in the local college sports scene and became one of the school’s first players to secure an NIL deal.

She’s part of an NIL Athlete program with the Pittsburgh-based sports event planners P3R, which spotlights players in underrepresented sports to advance the company’s mission to “keep Pittsburgh moving.”

Brunner said NIL opportunities are “a great way to get college athletes out there and into the world.”

Her role involves filming a monthly video sharing workouts, answering fan questions and talking about her accomplishments. For this, she receives $500 a year.

“Any amount was great for a college athlete playing three sports,” said Brunner.

She’s very aware of the disparity between athletes’ earnings and isn’t a fan of the clearinghouse and tighter NIL deal regulations introduced by the settlement. While Division III schools aren’t included, she’s confident that some of the funding changes will trickle down.

Several state legislatures have passed bills aimed at making it easier for athletes and schools to navigate the new revenue-sharing model.

Days before the settlement was finalized, three Pennsylvania House representatives introduced legislation targeting NIL earnings. Rep. Aerion Andrew Abney, whose district includes Pitt’s Oakland campus, said his bill would put the state on par with others that have prohibited the NCAA’s compensation limits on money from NIL collectives.

He said the bill would allow schools in the state “to have the same type of, if not more, of a competitive edge” than those in neighboring states by protecting student athletes against exploitation. As a trustee on Pitt’s board, he sent the legislation to the university for review.

Across the aisle, House Republican Leader Rep. Jesse Topper, of Bedford and Fulton counties, and Rep. Perry Stambaugh, R-Juniata and Perry counties, issued a memo highlighting their forthcoming legislation that aims to develop long-term financial security for college athletes. Their bill would require schools to provide financial literacy courses to players and offer them the opportunity to put NIL earnings in trust accounts.

“We do need to bring a little order,” said Topper, to what he called the “Wild, Wild West” of NIL.

“We see what’s going on with the courts. The more that we can as public policymakers set rules and guidelines through policy, the less uncertainty that’s out there,” he said.

When interviewed by PublicSource, neither Topper nor Abney had seen the other’s legislation. Abney said he shared his bill with the Republicans and was positive that there would be something to glean from both, as the legislature also tries to finalize a budget.

“At the end of the day, there’s got to be something in … their legislation and my legislation that we can, during this budget negotiation, find a solution to this topic.”

Maddy Franklin reports on higher ed for PublicSource, in partnership with Open Campus, and can be reached at madison@publicsource.org.

Ayla Saeed is an editorial intern at PublicSource and can be reached at ayla@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Jake Vasilias.

NIL

Best college baseball players ever, sport’s best rivalry, biggest issue: Analysts roundtable

OMAHA, Neb. — The college baseball world has made its annual pilgrimage to Charles Schwab Field for the 75th College World Series. It’s a diverse field with six different conferences (plus one independent) represented — a refreshing change after last year’s CWS included four teams from both the ACC and SEC. I asked some people […]

OMAHA, Neb. — The college baseball world has made its annual pilgrimage to Charles Schwab Field for the 75th College World Series. It’s a diverse field with six different conferences (plus one independent) represented — a refreshing change after last year’s CWS included four teams from both the ACC and SEC.

I asked some people who cover the sport for their thoughts on the state of the game, the best players they have ever seen, the best rivalry in the sport and the best game they have witnessed.

The panel:

- Chris Burke, ESPN

- Mike Ferrin, ESPN/Sirius XM

- Aaron Fitt, D1 Baseball

- Kyle Peterson, ESPN

- Mike Rooney, ESPN

Best position player you have seen in college baseball?

Burke: I’m going to say Wyatt Langford. I thought the two years (2022-23) he put together at Florida, … he was almost flawless in the outfield. He ran the bases as hard as anybody I ever covered, especially for a superstar. And you felt like he was going to hit an extra-base hit every at-bat. So I’ll just go in the era that I’ve been covering the sport.

(Vanderbilt’s) Dansby (Swanson) was fantastic. The game wasn’t quite as offensive when he played. There’s a little recency bias there (with picking Langford). Alex Bregman (LSU) was more spectacular to me on defense than he was on offense. Now he’s become a Hall of Fame hitter.

And then from my playing career, I would say probably Mark Teixeira (Georgia Tech). Mark Teixeira was probably the most gifted college player I was ever on a field with.

Wyatt Langford had a career 1.217 OPS at Florida. (Steven Branscombe / Imagn Images)

Ferrin: You know who was great? It was Trea Turner at NC State. There’s a good story here. They lost to UCLA (in Omaha) the year UCLA won the national championship (2013), and one of the things that (Turner) did postgame was explain exactly how Nick Vander Tuig, who was the Saturday starter for UCLA, was able to get guys out, because he was able to use his fastball at the top of the zone. He had one of those fastballs that had ride on it before we had the data to back it up, even though it was 92 mph.

Somebody relayed that to John Savage, the UCLA coach, in the press conference, and Savage’s jaw hit the table, and he was like, “Man, I thought that guy was good. I didn’t realize he had that kind of baseball IQ. That guy’s unbelievable.”

And Savage went on for, like, 45 seconds talking about how unique a player Trea Turner was, because in addition to having all of these incredible skills, he had this innate ability to understand the game. So that’s one that really stands out to me, even though he probably isn’t, like, the best of this era. But man, he had it at that moment. As a sophomore.

Fitt: I was living in Southern California for three years during the same three years that Kris Bryant was at San Diego, and just the fact that the guy hit more home runs as a junior (31 in 2013) than about two-thirds of the college baseball teams hit — he was a monster among boys or whatever you want to say. It felt like Babe Ruth, where he’s hitting more home runs than a bunch of teams hit. And he could do a lot of stuff. You could move him around a little bit. He was never known as a defensive whiz, but he played solid enough third baseman, right field, wherever, and he could run better than you thought. The power was just special. He got better and better year over year. Great personality, magnetic. And I think just because of the era that he dominated in and the degree to which he dominated, that would have to be my answer.

Peterson: Mark Kotsay (Fullerton State). I played against him (while at Stanford), so maybe that’s part of it. … We played him Game 1 of the College World Series (in 1995). Well, first of all, the first college game I ever played in was at Fullerton. And I knew who he was, but I didn’t know a lot about him. And about three pitches later, he had a line drive right off my quad that I could feel the entire year.

And then they beat us in Game 1 of the College World Series that year, and Kotsay had a couple hits and then trotted in from center field to close the game in the ninth inning. He was, for me, like the ultimate college baseball player. And obviously he had a great big-league career, and now he’s managing the big leagues. But that’s the best one for me.

Rooney: I want to say Dustin Pedroia, but I coached him (at Arizona State, 2002-04) and I saw him every day for three years. He was the national defensive player of the year and the only MVP of Arizona State baseball for three consecutive years. Not even Barry Bonds did that.

I want to give you two, since I coached Pedroia. I’m going to do this: I’m going to say Chris Burke (at Tennessee). He almost hit .500, 50 stolen bases, 20-plus home runs (.435, 49 stolen bases, 20 home runs in 2001) and ran their defense from the middle of the field. Like, just a do-everything player.

Who’s the best college pitcher you have ever seen?

Burke: Paul Skenes, end of statement. He had the aura of nobody else. The only pitcher I’ve ever been around that had his aura was Roger Clemens. And I was fortunate to play with him for parts of three seasons (in the major leagues). But there was just something very unique when you were around Paul Skenes. And then the pitchability, combined with just the pure stuff, was a combination that to me was like nothing I’d ever seen in a college game.

Ferrin: It’s either Skenes or (Stephen) Strasburg. Strasburg was incredible, too, but what Skenes was able to do … he didn’t have the best slider, he didn’t have the best fastball — (LSU teammate) Ty Floyd’s fastball, metrically, was better — it was just the fact that he knew how to pitch, his competitiveness, the way he continually improved, and the way that he carried himself. That guy was unreal. That’s one of the great college seasons of our time.

Fitt: So I would have said Stephen Strasburg for a long time until Skenes. But everyone’s gonna say Skenes, so I’m gonna give you Strasburg. He was insane. Even the first time I ever saw him, it was his freshman year (2007), and it was on a random day, it’s like a Tuesday game, I think. And people were kind of whispering, “You gotta see this kid. He is so big, he blocks out the sun.” It’s just a ridiculous, explosive fastball coming at you. Didn’t hear a lot about this kid coming out of high school. He was overweight and didn’t really work hard enough, and then he got to San Diego State and something clicked for him. The coaching staff, Tony Gwynn and (pitching coach) Rusty Filter, deserve a lot of credit, but so does Steven, of course.

By the time he was a junior, he was just a monster. It’s 96 to 100 with command in an era where you didn’t even see that kind of velocity very much. Ridiculous breaking ball with command. Plus-change up with command. And the ability to miss bats and throw quality stuff that was just so much better than everybody else’s stuff at that time. The stuff he did was absurd.

Peterson: Skenes. Before that, I probably would have said (Stephen) Strasburg, because I saw Strasburg in college when he was at San Diego State. But Skenes was as good as stuff as you would ever want to see, but then the control of Jamie Moyer or (Greg) Maddux or somebody like that. And I’ve never, in the college game, I’ve never seen the combination of as good a stuff as anybody in the country and as good a control as anybody in the country. And Skenes had that, and obviously, it continues to work out fairly well for him.

Rooney: Best one I coached against was Mark Prior (at USC). Best one I’ve seen is Paul Skenes. With Prior, it was Greg Maddux command with the best fastball in college baseball at the time. And Skenes, just like a ferocious competitor, generational arm talent.

Name a player who ended up being a much better pro than you thought

Burke: This is way back from my first year, second year broadcasting. It was Kyle Farmer, shortstop at Georgia (2010-13). Ended up being a really good major league shortstop for the Reds. I think he was an (eighth-rounder). I think he was a senior sign, and you look up, and he’s had a really nice career.

Ferrin: Pete Alonso (Florida, 2014-16). I thought he was sort of an Ivan Melendez (Texas) type, a big power guy, then he was going to get to pro ball and he was going to really struggle. What I didn’t understand was the guy really knew how to hit. I think even now, he still doesn’t get appreciated for how good of a hitter he is. He knows how to use the middle of the field. He knows the situations that call for him to drive in a run. That wasn’t readily apparent to me when he was at Florida.

He also wasn’t the biggest star on those teams. He was a little bit further down on the list. And he wasn’t the most dynamic presence. I had no idea he was going to be the player he is now. Testament to his work ethic and his intelligence. And he’s also got way better as a defender.

Fitt: I’ll just go back to my first year at Baseball America. Justin Turner was a nice kind of rugrat grinder from Cal State Fullerton (2003-06). “Red” Turner. He was a seventh-round pick or something, a senior sign. Never really hit for power. He was a great college player. I loved him as a college player. He would take a lot of walks. But I didn’t ever think that guy was gonna go be a plus-home run hitter in the major leagues and go to a bunch of All-Star games and be a vital part of championship teams. Especially after he got released. Who was it, the Mets, who released him? That’s a cool story. That guy just never struck me as anyone who would hit for power and be an impact big leaguer.

Peterson: Brandon Woodruff (Mississippi State, 2012-14) would be on that list. He’s had a hell of a run from a mound standpoint.

I played with a dude named Eric Bruntlett (Stanford, 1997-2000) that played in the big leagues for seven or eight years and won a ring or two, and I don’t know that he would have been the guy off our team that we would have picked to play the longest. But he played longer than anybody.

I can tell you this: I saw Aaron Judge (Fresno State, 2011-13) in the home run derby here, the college home run derby, and nobody would have thought … you thought the guy’s physical and talented and everything else, but he could go down as one of the greatest hitters ever by the time he gets done. So Judge is probably on that list. Not to say that people didn’t think he’d be good, but I don’t think anybody could have thought he’d be this good.

Rooney: Steven Kwan. He was on that 2018 Oregon State that won it all. Oregon State had four first-round picks. They had Cadyn Grenier, they had Nick Madrigal, they had Adley Rutschman, and they had Trevor Larnach, but they also had Steven Kwan (who was drafted in the fifth round). And I bet you Steven Kwan’s WAR this year, I’d have to look up Rutschman’s, but I bet you Steven Kwan’s WAR is better than any of those guys. (Note: Kwan’s WAR is 2.8. Rutschman’s is 1.1.)

What is the best rivalry in college baseball right now?

Burke: I would say probably Tennessee and LSU. Past two defending national champions, two coaching staffs, two athletic departments, two fan bases that are all in it. I think Arkansas, with that group, would be right there in it. Texas A&M is pretty good, too. I know I gave you a lot, but it feels like it’s hard to (pick one). Tennessee-Vanderbilt is pretty good, too. It feels like there’s a lot of budding SEC rivalries just because of the all-in nature. There are way more teams that are all-in.

Ferrin: The SEC versus the SEC. I think any time that you have those power conference teams — I hate to cop out with SEC versus SEC — but I think those are all pretty good. I think Texas A&M versus Texas right now is a little bit spicier because of (Jim Schlossnagle) leaving (Texas A&M for Texas) last year, so I think that’s a good one. You know, I think those are ones that really stand out to me, in that conference, just because the places are all packed and most of them are a little bit bigger than the other places. It just creates more energy that you expect out of a rivalry.

Fitt: I think you have to say Tennessee-Arkansas at the moment. It’s kind of the one that feels like it’s got the most juice. LSU-Arkansas also has a lot of juice. Those SEC deals, they just feel a little bit different. Traditionally, I still think Clemson-South Carolina, when those (teams) are both good, it’s awesome. But obviously, those programs are not where they were in 2010, when they were both in Omaha. That was something special. But at this particular stage, I think it’s shifted toward those SEC rivalries.

Peterson: Ole Miss-Mississippi State is always going to be there, just because of being within the state. The whole Florida component between Florida, Florida State, Miami is interesting, but they do it differently. (Florida) plays Miami on the weekend every year and they play Florida State in three midweek games, so that’s a little bit different. Tennessee-Arkansas has turned into a really good rivalry. I don’t know that there’s one.

Rooney: I would say Tennessee and Vanderbilt.

What is the college game you’ve ever seen?

Burke: I would say the Skenes vs. Lowder (LSU vs. Wake Forest in the 2023 CWS). Ends in a walk-off home run by superstar player Tommy White. Two major league All-Stars on the mound. And it was a night game. I think we had Roger Clemens on the broadcast, like, early in the broadcast. It was just a night you’ll never forget.

And there were a couple of legendary plays — Tre Morgan threw somebody off the plate on just an incredible defensive play. You know, there are just so many flash points within the game. But more than anything, you’re like, “We’re watching two major league All-Stars pitching in college.” And I know Lowder hasn’t made an All-Star team yet, but he sure feels like he’s going to. And Skenes is on his way to No. 2.

Ferrin: Skenes-Lowder, without a doubt. It’s so rare to see a pitching matchup that actually lives up to the expectations like that. And that game had everything. And then the coolest moment … so when Tommy White hits the walk-off homer and celebrates with his team, and Cam Minacci, who’s the pitcher for Wake, and Bennett Lee, who’s the catcher for Wake, were friends of his growing up. And what did he do? He went over to console them afterwards. That’s like one of the great moments of sportsmanship in NCAA history, and I hope everybody always remembers that. Because in the end, these guys love competing against each other, but because they’ve all grown up playing together, they all know each other, and a lot of times they’re friends, and those relationships matter more than the wins and losses. I thought that was really cool.

Fitt: There are only two answers here. It’s the Skenes-Lowder game or the last game of Rosenblatt (in 2010). It was awesome. The fact that the last game of that ballpark ended on a walk-off in the 10th inning, two great teams, it was the start of that South Carolina dynasty. You got Whit Merrifield and Scott Wingo in the middle of it. You got Trevor Bauer out of the bullpen warming up (for UCLA). Incredible game and just the whole feeling there. It was so bittersweet. All of us were heartbroken about leaving that ballpark, and it was just awesome that they could send it out with a thriller like that.

Peterson: The Wake Forest-LSU game a couple years ago was as good as I’ve ever seen here. I’ll never forget the last game at Rosenblatt when it was South Carolina-UCLA and (Whit) Merrifield got the hit down the right-field line. I think some of that was just because it was the last game at Rosenblatt, maybe. But yeah, the LSU-Wake, really that entire tournament. There were some games that year that were as good as we’ve ever seen here.

Rooney: I think everyone’s going to give you Skenes vs. Lowder. So I’m going to give you a different one. I got to call Kumar Rocker’s 19-strikeout no-hitter in 2019. People forget this, but Duke had already won Game 1 of that Super Regional. That Vandy team was one loss from their season ending, and Kumar Rocker, a true freshman, steps up and throws a historic game to completely flip the momentum of that Super Regional.

What is the best part of college baseball in 2025?

Burke: I think the exposure. The spotlight is much brighter than it’s ever been. Both with the digital networks, the conference network and then ESPN’s commitment to the sport. Combine that with a social media presence that all these teams do a really good job of, I just feel like these players are on a much bigger stage than they’ve ever been on.

Ferrin: I think it’s the atmosphere. To me, it’s these 3-, 4-, 6,000-seat stadiums that are on campuses in places that they really care about college baseball — which is growing too — and that you’re filling them with fans who have the same energy that you have for college basketball. Even in places like Manhattan, Kansas, like where they sell out. Being able to create those environments is really rewarding for the sport because you can’t not want to be a part of that if you get to experience it.

Fitt: I like the product, personally, better than Major League Baseball because of, and it’s gonna sound cliche, but it’s just the energy. It’s the energy of it. Especially the postseason, the on-campus sites. I don’t think there’s anything like it when you’ve got the home Regionals on-site and the Super Regionals. It’s just electrifying, and I think the drama, that part of the product, really holds up. I love the format of college baseball, all the way through the weekend series structure. I like the fact that it’s not 162 games. I think the season makes a lot of sense. It’s drawing in a lot more fans than it used to for a good reason. It’s not as polished a product as Major League Baseball on the field, obviously. That’s part of the fun of it. It leads to some unpredictability, and I think it’s just compelling theater.

Peterson: I love it because of the fan bases, and it’s college (athletics). When you go to some of these environments, Arkansas, LSU, Ole Miss, Mississippi State, Florida State, whatever — you can name a bunch of them, it’s like college athletics fans. And I just think there’s something really cool about that. From a player standpoint, I just think it would be really cool to play in those environments. So, for me, it’s the environments that these kids are surrounded by.

The level of play and everything else continues to get better, and we’ve seen that based on the draft. The draft is more college-based now than it’s ever been because Major League Baseball realizes that this is a really good way to develop players. So I’d say both of those. I love going to college baseball stadiums, environments, towns. That’s my happy place.

Rooney: I would say this (pointing to the field). We have an Omaha field that represents seven different conferences or non-conferences, depending on how we want to describe Oregon State. We knew we didn’t really have a super team like we’ve had the last four years, but this year, for this to play out the way it did, to go from a year where you only had two leagues in Omaha, to have seven different affiliations represented, is super cool and very encouraging.

What is the sport’s biggest issue?

Burke: Probably the roster uncertainty. How many spots are going to be available? How is that going to limit opportunities? I think it’s interesting. A decade ago, we were all clamoring for more scholarships, and now with NIL, the scholarship delta has kind of been fixed. In one regard, you want to be thankful that kids are, for the most part, going to have a lot more aid, if not full aid. But if it goes from 40 to 34 (roster spots), you’re talking about six players per 310 teams. That’s a lot of players that aren’t going to get opportunities to play Division I baseball. So I think figuring out what that is and what the new normal is going to be is probably what I would consider to be the biggest issue.

Ferrin: I want there to be more consistent parameters from the committee before the season starts on what’s gonna constitute the decisive factors (to get into the NCAA Tournament). So, like every year, we see a little bit of variation, but we never find out until after the fact that this was the year that nonconference strength of schedule mattered, or this was this, this was that. So I think that there’s something that can be done to try and better codify or balance out, or give coaches at least an idea of what’s gonna matter, especially since they’re having to schedule a couple of years out. I think that’s one that really stands out to me as being important, is that you wanna make sure that everybody is on even footing, at least in terms of what they understand.

Fitt: I think it’s just the issues facing college sports writ large. Where are we headed with NIL, the revenue-sharing stuff? Are we going to have too much of a gap between the haves and have-nots, when you’ve got schools funding 34 full scholarships and others are still down there at 11.7 or whatever? I think it’s going to be challenging to navigate.

There’s obviously a lot of upside potential for the sport, considering how long we were stuck at 11.7 and all we wanted was a few more scholarships, right? And now, all of a sudden, it’s just this whole new world right in front of us, and there are gonna be a lot of programs left behind. And I think the depth of college baseball is an important part of the sport. It’s nice that guys can have the experience of playing college baseball at 300-and-something schools.

You talk to the coaches at Central Connecticut State, and they go down to a big venue for a Regional at Georgia or Arkansas or whatever and just to see those guys soak in that experience, it’s magic. It’s part of what makes this sport special, and if we wind up in a situation where it’s just two big mega conferences and everybody else is just left behind, I think we’ll really lose an important part of the soul of college baseball.

Peterson: I would just say money in general. I don’t think anybody knows yet what this House settlement is going to be, and, ultimately, if that’s detrimental to the game at all. So I think the biggest challenge or potential issue right now is … the first thing is everybody’s got to know the rules. They don’t know them yet. So if the rules are what it sounds like they will be, they’ll continue to be a pretty significant financial gap. But that’s also the reality of the world.

So that would be my biggest concern, is whether or not that financial gap between those that can afford it and those that can’t creates way too many haves and way too many have-nots. But I think the field this year would indicate that that may not be the case.

Rooney: I would say our biggest issue is rosters. We have an unlimited fall roster, but then we’ll have this 34-man roster on Dec. 1 as part of the (House) settlement. And I think that both concepts are flawed, and somewhere in the middle would be a much better answer. So I’d say roster management is the biggest issue.

(Photos of Paul Skenes, Mark Kotsay: Scott Clause / USA Today Network via Imagn Images, Andy Lyons / Getty Images)

NIL

Otega Oweh says NIL hasn’t changed locker rooms in college athletics

Mark Pope and the Kentucky Wildcats received some massive news a few weeks ago with the return of Otega Oweh. Oweh had an opportunity to enter the NBA Draft and entertained it for a few months, but felt it was best for his career to return to Lexington for year two in blue and white. […]

Mark Pope and the Kentucky Wildcats received some massive news a few weeks ago with the return of Otega Oweh.

Oweh had an opportunity to enter the NBA Draft and entertained it for a few months, but felt it was best for his career to return to Lexington for year two in blue and white.

Oweh exploded on the scene after transferring from Oklahoma, averaging 16.2 points, 4.7 rebounds, and 1.7 assists last season.

With the world of NIL, it is safe to assume Oweh is making enough money to come back and play for Kentucky again and pass on the NBA for the time being.

With the changes in the NCAA, Oweh made sure to comment on the changes over the past few years.

“They’re paying us,” Oweh responded with a laugh via On3’s Daniel Hager. “That’s it. That’s a great thing for sure, but I don’t really be keeping up with the settlement stuff like that. As long as we’re getting paid, that’s good for me. Anything extra, that’s cool.”

With the NIL growth and transfer portal explosion, Oweh was asked if it has changed the locker rooms in college athletics.

“Nah, because when I came into college, that’s when NIL started. That’s what I’m used to, really. I’m a senior now, so the guys after me it’s going to be the same with them. It hasn’t really changed anything for me.”

Oweh will likely make more money before and throughout the season with his return to Lexington but having him back is massive for the National Championship aspirations.

NIL

John Blackwell says John Tonje is ‘the Russell Wilson of hoops’ for Wisconsin Badgers

The Wisconsin Badgers have had good luck with veteran college players transferring into their athletics programs and breaking out for one big year before heading to the pros. In 2011, it was quarterback Russell Wilson coming in from North Carolina State and leading the football team to the Rose Bowl. In 2024-25, it was guard […]

The Wisconsin Badgers have had good luck with veteran college players transferring into their athletics programs and breaking out for one big year before heading to the pros.

In 2011, it was quarterback Russell Wilson coming in from North Carolina State and leading the football team to the Rose Bowl.

In 2024-25, it was guard John Tonje transferring from Missouri to carry the men’s basketball team to the Big Ten Championship games.

Tonje’s teammate John Blackwell thinks he’ll be remembered similarly to the standout quarterback.

“They’re going to call him the Russell Wilson of hoops for the Wisconsin Badgers,” Blackwell told “The SchuZ Show” on YouTube. “He did some stuff that was just crazy, like dunking on people, shooting clutch threes. He’s going to go down as one of the greatest Badgers players that have come through in recent history.”

Both Tonje and Wilson set records during their short time at Wisconsin, elevating their game to a new level for the Badgers.

Part of what cemented Wilson’s legacy was the success he went on to have in the NFL, winning a Super Bowl with the Seattle Seahawks.

It wouldn’t be fair to put those expectations on Tonje, but he could go overlooked in the draft the way Wilson was in his own sport and make him that much easier to root for as an underdog story.

Blackwell is trying to follow in Tonje’s footsteps and lead the Badgers on another deep run of his own.

NIL

The evolving landscape of college athlete pay

Cat Flood recounted the DM she got from the Pennsylvania Beef Council around two years ago that started her down the road of cashing in on college volleyball stardom. The nonprofit wanted her to promote its mission of “building beef and veal demand with consumers of all ages.” She recorded a series of videos for […]

Cat Flood recounted the DM she got from the Pennsylvania Beef Council around two years ago that started her down the road of cashing in on college volleyball stardom. The nonprofit wanted her to promote its mission of “building beef and veal demand with consumers of all ages.”

She recorded a series of videos for her Instagram, one of which got over a million views. In the post, she invited followers along a day in her life — notably, eating jerky for her first snack, steak for lunch and later on, more jerky. The council paid her $1,000.

Deals like this are commonplace in today’s college athletics landscape, where for four years, athletes have been profiting from use of their name, image and likeness [NIL].

“NIL made us all influencers,” Flood said.

As one of the University of Pittsburgh’s most popular athletes, Flood — who recently graduated — benefited from NIL deals, averaging one or two a month, and saw how their introduction changed the nature of college sports.

And more change is on the horizon with the June 6 approval of a landmark NCAA settlement letting colleges pay their athletes that takes effect July 1. Universities in the former Power Five conferences (recently reduced to four), including Pitt and Penn State, will each have to split $20.5 million annually between players for a decade. The yearly amount will increase incrementally.

We are local reporters who tell local stories.

Subscribe now to our free newsletter to get important Pittsburgh stories sent to your inbox three times a week.

While the settlement ushers in more money for athletes, it’s unlikely to be spread evenly, and certain NIL deals will be scrutinized for the first time. Uncertainty about how the millions will be distributed and exactly how the settlement terms will be enforced has rattled college athletes and spurred state lawmakers alike.

PublicSource spoke to several athletes, state representatives and NIL experts about their thoughts on the second big change in compensation in just this decade. Here’s what they had to say.

Antonio Epps, Duquesne University

School division: Division I, outside of Power 4 conferences

Year: Senior

Sport: Football

Recent NIL deal: None

Dream NIL deal: Pizza Hut

Before NIL came into play, Epps said, “there was always talk about how being a college athlete was very similar to working a 9-5, in a sense.”

He was a sophomore when the NCAA allowed athletes to have NIL deals and became a part of Duquesne’s Red and Blue NIL collective. Through this, he’s able to make money from merch and generally feels NIL has been a good thing.

“It can help out a lot of people who didn’t have as much money coming into college,” he said.

Duquesne is one of the schools that can choose to opt into sharing a portion of their athletics department revenue with athletes, but isn’t required to do so.

A university spokesperson confirmed that Duquesne is opting in.

Epps said that although the conversation has been about athletes, they’re being left in the dark when it comes to understanding what impact this will have on them.

“A lot of the conversations that happen, happen around us, but a lot of us are not told the [parameters] of what is being said.”

When the NIL policy first went into effect in 2021, it was expected that money would largely come from endorsement rights opportunities — think brand deals like Flood’s Pennsylvania Beef Council posts. Then collectives emerged, said University of Illinois labor and law professor Michael LeRoy.

Collectives are groups that pool donations to pay athletes for use of their NIL, while facilitating deals for them. While these are usually school-specific, they’re operated independently, though there’s often some level of collaboration with the college.

Once athletes sign contracts with collectives, there’s an expectation that they’ll get paid, but which players are paid and how much is up to the discretion of the collective’s head. Last fall, the founder of Pitt’s collective, Alliance 412, along with the university’s football coach, stopped paying all members of the team, instead compensating only some to incentivize better performance.

The NCAA settlement retains a longstanding ban on compensation solely related to athletic performance or participation. Nonetheless, the NIL system has been called “pay for play,” because it seemingly rewards performance in many cases.

“There’s so much pent-up demand among supporters and the businesses … neither the laws nor the rules have caught up with the market supply of NIL money for athletes,” LeRoy said.

A majority of NIL funds come from collectives, not endorsements, sponsorships or appearances, according to Philadelphia-based NIL agent and attorney Stephen Vanyo. When he’s looking at contracts with collectives for clients, he said a player’s NIL value is being assessed based on what they will bring to a team. This is subjective, but factors include stats and social media following.

None of the athletes PublicSource interviewed disclosed their NIL values. Some of them did not have the figures.

LeRoy, who has researched NIL earnings, said that men outearn women 10:1 in deals, with the most money going to men’s football and basketball players. The settlement is expected to do little to remedy this, opening the doors for lawsuits against schools under Title IX, which requires schools to provide equal financial assistance opportunities to men and women athletes.

With no stipulations on how colleges have to divvy up the $20.5 million, experts have predicted that as much as 70-90% will go to men’s football, men’s basketball and women’s basketball, in that order.

Cat Flood, University of Pittsburgh

School division: Division I, ACC

Year: Graduated in 2025

Sport: Volleyball

Recent NIL deal: Saxbys

Dream NIL deal: World Wildlife Fund or Free People

Last year, Pitt’s volleyball team was ranked third in the country by the NCAA, finishing the 2024-2025 season 33-2.

Flood joined the team in 2020 after one visit to a university volleyball clinic. “I fell in love with it on the spot,” she said.

Recruiting, to her, was all about considering, “Where am I going to have the best four years?” not where she could get the most money in NIL deals. She never joined Alliance 412.

“I didn’t love the idea of NIL, I had seen what it had done to a lot of players,” she said. “They were playing for the money, they were transferring for the money.” She preferred to use NIL to promote local businesses in mutually beneficial, ethical arrangements.

However, after the volleyball team’s continued success, she began to regret not taking NIL more seriously. She saw NIL funds flowing to men’s football and men’s basketball, which she believed was fair due to viewership. But she noted that despite her squad being “the best team at the university … the women’s side was getting nothing.”

With players now getting paid a portion of the revenue that college athletics departments receive, she wants to see women’s volleyball benefit.

“I hope that we bark up some NIL trees.”

In the year it’s taken for the settlement terms to be negotiated and finalized, schools have prepared to start paying athletes. One way was by presenting recruits with NIL contracts that would only become effective after the settlement’s approval.

Alex Guminiski, a Pittsburgh-based NIL agent and attorney, has seen over 20 of these so far — some for Pitt recruits — but due to confidentiality clauses, couldn’t give more details. He stressed, though, that “it’s not pay for play,” but rather “licensing deals.”

“The school is asking the player to grant the school the license to use their NIL in all sorts of media,” Guminiski said.

LeRoy, the professor who obtained similar contracts from schools in the Big Ten and SEC conferences, said players are being asked to give away “an irrevocable right” to their collegiate NIL. These terms aren’t negotiable, he added.

“They are going to be paid for this, and in many cases, paid well. But again, people likely don’t know what they’re signing.”

LeRoy worries about the exploitation of athletes, especially those without an agent. He sees these contracts as a way to sidestep the perennial question of whether college athletes are employees of the schools they play for — another area many experts believe will play out in the courts.

Vanyo called the settlement “another half measure” because of the legal challenges it is likely to ignite. He said the only sustainable solution for stabilizing the industry is to allow athletes to unionize and collectively bargain, as players in professional leagues do. Then, there’d be what he described as a “semblance of fairness.”

“It’s the only thing we’ve seen work in the American sports model,” he said.

Ryan Prather Jr., Robert Morris University

School division: Division I, outside of Power 4 conferences

Year: Junior

Sport: Basketball

Recent NIL deal: C4 Energy

Dream NIL deal: Nike

Ryan Prather Jr. has had a long journey to Pittsburgh. After playing at the University of Akron through his first two years of college, he decided to transfer and commit to RMU in 2024.

“I wanted somewhere I could go and showcase what I could do,” he said.

He changed schools in part to be closer to home and family, but also due to the opportunities he could envision. After transferring, he joined RomoRise, an NIL collective specifically for RMU students, and has taken advantage of the deals presented to him.

As the settlement is sure to prompt changes to deals, Prather said, “It definitely has an effect on anyone who’s trying to play in college … they come in with a certain amount in their head.”

Prather said he understood the benefit of college athletes getting paid to do what they love. “The money helps you out in the long run because if you use up your money and save it up and invest, you can start early rather than waiting until after college for your career to get started.”

The downside: “It’s kind of hard at the same time because no team is going to stick with each other.” With teams changing every year due to players leaving, it can be difficult to produce a cohesive team environment.

“More money doesn’t always mean a better situation.”

The NCAA has been trying to wrangle what it views as an out-of-control stream of money going to athletes via NIL deals over the past few years, in part because athletes are transferring schools at record numbers, which some believe is due to money offered by collectives.

Under the settlement’s rules, third-party NIL deals valued at or above $600 will be reported to a clearinghouse run by consulting firm Deloitte. The goal, LeRoy said, is to regulate the market.

The clearinghouse will determine if deals fall under “pay for play” and evaluate their fair market values. Deals have to be approved before an athlete can receive the funds.

Little is known about the specific criteria needed for compliance, but experts told PublicSource that there isn’t a set fair market value for any NIL deal, and trying to determine one is next to impossible.

Vanyo said fair market value in the industry is simply “what somebody’s willing to pay.”

“In no other industry do we have … a clearinghouse that then says, ‘OK, this is a fair salary,’” he continued.

Some experts describe the clearinghouse as a way to scale back how much some athletes are earning.

“While nobody knows for sure how this is going to come out, the clear implication is that most of the NIL deals, particularly in men’s revenue sports — football and men’s basketball — will not be accepted as fair market value,” LeRoy said. A new College Sports Commission, separate from the NCAA, could then reject such deals.

It’s been reported that Deloitte officials said 70% of past deals from collectives would be rejected under the clearinghouse.

Unsurprisingly, legal challenges by those with rejected deals are expected to follow.

Aurielle Brunner, Chatham University

School division: Division III, Presidents’ Athletic Conference

Year: Graduated in 2025

Sport: Track and field, Soccer, Basketball

Recent NIL deal: P3R, a local event management organization

Dream NIL deal: Nike

Brunner believes college athletes are valued professionals and views the settlement as a “huge step for sports.”

She holds 10 All-American awards for her track and field success. As Chatham University’s most decorated athlete of all time, she quickly stood out in the local college sports scene and became one of the school’s first players to secure an NIL deal.

She’s part of an NIL Athlete program with the Pittsburgh-based sports event planners P3R, which spotlights players in underrepresented sports to advance the company’s mission to “keep Pittsburgh moving.”

Brunner said NIL opportunities are “a great way to get college athletes out there and into the world.”

Her role involves filming a monthly video sharing workouts, answering fan questions and talking about her accomplishments. For this, she receives $500 a year.

“Any amount was great for a college athlete playing three sports,” said Brunner.

She’s very aware of the disparity between athletes’ earnings and isn’t a fan of the clearinghouse and tighter NIL deal regulations introduced by the settlement. While Division III schools aren’t included, she’s confident that some of the funding changes will trickle down.

Several state legislatures have passed bills aimed at making it easier for athletes and schools to navigate the new revenue-sharing model.

Days before the settlement was finalized, three Pennsylvania House representatives introduced legislation targeting NIL earnings. Rep. Aerion Andrew Abney, whose district includes Pitt’s Oakland campus, said his bill would put the state on par with others that have prohibited the NCAA’s compensation limits on money from NIL collectives.

He said the bill would allow schools in the state “to have the same type of, if not more, of a competitive edge” than those in neighboring states by protecting student athletes against exploitation. As a trustee on Pitt’s board, he sent the legislation to the university for review.

Across the aisle, House Republican Leader Rep. Jesse Topper, of Bedford and Fulton counties, and Rep. Perry Stambaugh, R-Juniata and Perry counties, issued a memo highlighting their forthcoming legislation that aims to develop long-term financial security for college athletes. Their bill would require schools to provide financial literacy courses to players and offer them the opportunity to put NIL earnings in trust accounts.

“We do need to bring a little order,” said Topper, to what he called the “Wild, Wild West” of NIL.

“We see what’s going on with the courts. The more that we can as public policymakers set rules and guidelines through policy, the less uncertainty that’s out there,” he said.

When interviewed by PublicSource, neither Topper nor Abney had seen the other’s legislation. Abney said he shared his bill with the Republicans and was positive that there would be something to glean from both, as the legislature also tries to finalize a budget.

“At the end of the day, there’s got to be something in … their legislation and my legislation that we can, during this budget negotiation, find a solution to this topic.”

Maddy Franklin reports on higher ed for PublicSource, in partnership with Open Campus, and can be reached at madison@publicsource.org.

Ayla Saeed is an editorial intern at PublicSource and can be reached at ayla@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Jake Vasilias.

-

College Sports2 weeks ago

College Sports2 weeks agoIU basketball recruiting

-

Health2 weeks ago

Health2 weeks agoOregon track star wages legal battle against trans athlete policy after medal ceremony protest

-

Professional Sports2 weeks ago

Professional Sports2 weeks ago'I asked Anderson privately'… UFC legend retells secret sparring session between Jon Jones …

-

Professional Sports2 weeks ago

Professional Sports2 weeks agoUFC 316 star storms out of Media Day when asked about bitter feud with Rampage Jackson

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoScott Barker named to lead CCS basketball • SSentinel.com

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoJ.W. Craft: Investing in Community Through Sports

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoNASCAR Penalty Report: Charlotte Motor Speedway (May 2025)

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoRockingham Speedway listed for sale after NASCAR return

-

College Sports3 weeks ago

College Sports3 weeks agoOlympic gymnastics champion Mary Lou Retton facing DUI charge

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks ago2x NBA All-Star Reacts to Viral LeBron James Statement

Caitlin Clark

Caitlin Clark