Rec Sports

How Can We Optimize a Safe Return to Sport for Youth Athletes? Emergi

Introduction

Regular physical activity is one of the main contributors to optimize general health.1,2 Although regular physical activity provides many health benefits,3 such as fitness development at early ages,4 negative events sometimes happen. One of the most common negative consequences is injury. Injury is prevalent among young athletes. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention injury surveillance study,5 it was estimated 2 million injuries, 500,000 doctor visits, and 30,000 hospitalizations occur annually, which could be burdensome in both physical and psychological standpoints.6–8 Additionally, injury often leads to time loss from practices and competitions for young athletes as well as time away from their teammates.9,10 Furthermore, there is a financial burden associated with injury, which further impact organized team performance.11 Among these musculoskeletal injuries, some of the more serious musculoskeletal injuries require orthopaedic interventions, such as surgery.

One common sport injury requiring surgical intervention among young athletes is an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. The ACL tear is often observed in sports that involve cutting, pivoting, and jump-landing maneuvers such as basketball, handball, and soccer,12 and existing evidence suggests that the incidence of ACL tears is higher among young, healthy female athletes compared with their male counterparts who participate in similar sports.13 According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) data, female soccer and basketball players have 2.4 times and 4.1 times higher risk for an ACL injury than their male counterparts in the same sports at college level, respectively.14 The majority of athletes who sustain and ACL injury and hope to return to pivoting and cutting sports, go on to have an ACL reconstruction (ACLR).15 Following the ACLR surgery, post-ACLR rehabilitation is necessary to improve joint range of motion (ROM), muscular strength, and functional neuromuscular controls.16 After rehabilitation, sports medicine providers may use a battery of return-to-sports (RTS) tests to assess recovery of the surgical limb.17–19 These measures are often referenced to the contralateral limb and quantified by limb symmetry index (LSI).20–22 Recently, the importance of measures beyond physical function, specifically psychological readiness to RTS, is often assessed using tools such as ACL-Return-to-Sport-after-Injury (ACL-RSI).23,24

Many studies have reported recommendations for RTS and ACL-RSI testing following ACLR surgery.25,26 Among them, several systematic review and meta-analysis articles suggested that the outcome of the RTS tests are not associated with the future risk of ACL injury.27–29 This has been controversial since a safe RTS is a priority for all medical care professions including orthopedic physicians (orthopedic medical doctors), allied healthcare providers (physical/physiotherapists, athletic trainers), and psychological/psychiatric therapists because they are a part of this recovery process as healthcare practitioners. For athletes who complete rehabilitation and RTS tests following ACLR, re-integration into fields/court activity, with their teammates is a significant step forward and needs to be performed safely. In short, some studies27–29 report that there were no or inconsistent associations between current RTS test batteries and risk of secondary ACL injury (re-tear of graft and/or a new tear/injury to the healthy, contralateral knee). From the time of the ACL injury to the decision of RTS and return to competition, many healthcare professionals are involved. However, the literature that synthesized all of their clinical expertise and discuss the safe RTS is lacking. Therefore, the purpose of the current article was to discuss how to optimize a safe RTS from the perspective of multidisciplinary sports medicine healthcare practitioners and synthesize them with research-based evidence using a clinical scenario involving a female athlete following ACL injury.

Clinical Scenario

Who

A 19-year-old, competitive female college basketball player (position: small forward)

What Happened

During a basketball game, the patient jumped for a rebound and hyperextended her left knee on landing. She immediately felt significant pain and could not continue playing.

Diagnosis

ACL rupture, confirmed by MRI.

Special Note

The patient had a previous history of an ACL tear on the contralateral (right knee) 4 years prior when she was 15 years old. At that time, the hamstring tendon was harvested from the affected limb and used as a graft for her ACLR. Despite this being her 2nd ACL tear, her goal is to return to basketball activities.

ACLR Surgery

The patient had surgery 4 weeks following the ACL injury. At this time, ACLR with bone-patellar tendon-bone (BTB) graft procedure was performed.

Progress Following ACLR

Post-operative rehabilitation began immediately following her ACLR. Her initial post-operative course began without complications, with adequate pain control, and no concern for infection. Once the inflammation and pain had subsided, she started active and passive ROM exercises and isometric muscle contraction under the guidance of her physical therapist. Once she made further progress, she started performing isotonic exercises with near full ROM using a tubing band and weight at the ankle. She was able to jog at 3 months without noticeable pain or compensatory mechanics. From 3 months to 6 months, her rehabilitation exercises involved (basic) agility, balance, and plyometrics in conjunction with fundamental basketball movements. After 6 months, her rehabilitation incorporated more functional training including various sport-specific (basketball-based) drills.

RTS Test

At 9 months post-operatively, she performed a series of RTS tests with the following results:

a) Thigh circumference – 10 cm from top of the patellar

i. Right limb: 43.5 cm

ii. Left limb: 42.0 cm

b) Knee extension ROM

i. Right limb: −4 degrees

ii. Left limb: 0 degree

c) Knee flexion ROM

i. Right limb: 145 degrees

ii. Left limb: 142 degrees

d) Isokinetic test – Concentric contractions at 60 degrees/sec

i. Quadriceps: LSI 82%

ii. Hamstrings: LSI 86%

iii. Hamstrings/Quadriceps (H/Q) ratio: 58%

e) Hop tests for distance and time

i. Single-Leg Hop: LSI 80%

ii. Single-Leg Triple Hop: LSI 76%

iii. Single-Leg Crossover Hop: LSI 72%

iv. Single-Leg Timed Hop: LSI 84%

In addition to the three RTS tests, ACL-RSI was collected:

f) ACL-RSI (out of 100)

i. Overall scores: 51.2

ii. Confidence in performance subscale: 58.8

iii. Emotional subscale: 40.1

iv. Risk appraisal subscale: 55.4

RTS Recommendations/Perspectives

From an Orthopaedic Surgeon

This patient, unfortunately, underwent a second ACLR surgery: one for each knee, not revision ACLR. Evidence suggested that patient-reported outcome measures including Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and Lysholm scores of the revision ACL injury patients are much worse than primary ACL injury patients.30 Moreover, weaker muscle strength, lower Tegner activity levels, and more severe osteoarthritis signs were found in the revision ACL injury patients compared to the primary ACL injury patients.30 It was, indeed, unfortunate; however, could be considered as fortunate that the second ACL injury occurred in contralateral limb, not a revision (not a re-tear of the graft on the same, ipsilateral knee). From this reason, I am cautiously optimistic for her to gain good knee joint stability and neuromuscular function through a post-operative rehabilitation. Yet, I have a concern. Anecdotally, young athletes who sustained ACL injury two times, regardless revisions or contralateral tear, tend to move each of the rehabilitative milestones quicker than primary ACL injury patients. This may be because they have gone through rehabilitative exercises of each phase previously. The familiarity of the rehabilitative process may facilitate the swift pace. However, instead of aiming a speedy recovery, I highly suggest to take adequate time to perform rehabilitative exercises with good quality of movement. Another concern I have is a use of the LSI measures. Since she had an ACL tear on her right knee 4 years prior, it is difficult and some ways invalid to assess the stability, strength, and function of her left knee using LSI measures.

Overall, since she has already sustained two ACL injuries, it would be beneficial to examine morphologic factors (example, posterior tibial slop), familial history, concomitant meniscus or cartilage injury, and knee and general joint laxity. Then, depending on the identified factors and in scenario of another ACLR, additional surgical procedure such as anterolateral complex augmentation during ACLR including lateral extraarticular tenodesis (LET) or anterolateral ligament reconstruction (ALLR), or slope reduction osteotomy should be considered. Orthopaedic surgeons need to be fully aware of the risk of further ACL injury and conduct pre-operative planning for high-risk patients who wish to return to sporting activities.

From an Academic-Physiotherapist

Considering that she had also ACLR on her right knee 4 years ago (deficits in her right lower extremity may have persisted), the interlimb comparisons (left/right) should not be taken as the only performance index. Reference values for the isokinetic strength and jump test reference values are available for elite female basketball players after ACLR:31 as an example, peak torque/body weight values allow for better interpretation of the strength potential (when compared to LSI). Pre-injury screening data (eg pre-season team testing), when available, are also a valuable reference source.32 Following recent neuroscience research advances, it is crucial to include neurocognitive loads (and motor dual-task challenges) both in rehabilitation and testing (eg visual-cognitive hop tests), as performance deficits are not only related to the physical status of the athlete.33

As the young age and the two ACLRs put her at higher risk for further injury, her training in return to competition should/must be optimized, with the goal to possibly reach her pre-injury performance.34,35 Psychological readiness is associated with RTS and return to pre-injury level of performance.35,36 The ACL-RSI scores should be interpreted with caution, considering that the “optimal psychological profile” differs between individuals.36 Ideally, this scale should be further implemented during the RTS process, to monitor the changes in the psychological profile over time. Her overall score at 9 months post-ACLR (51.2 points) indicates that her psychological readiness for a potential RTS is not yet sufficient, and that she needs more time and work to regain her confidence mentally and emotionally.37 The strengthening and conditioning program should be intensified, as well as the basketball-specific training. Waters et al38 described a set of basketball-specific movement drills (skill drills, reactive drills, contact drills, and combinations of each of these). The training progression needs to be performed at many levels: from low-intensity to high-intensity drills, from 1:1 drills with the sport PT/ATC to group practice, from no-contact to contact drills (defensive/offensive).39 As the ideal test battery does not exist, the training drills are also used as test situations, where the staff (PT/ATC, coaches) evaluate the player’s ability to master technically, physically and mentally these basketball-specific and complex demands.40 The ultimate goal is to re-integrate the (optimally prepared) player in full-contact, unrestricted team practice, following shared-decision making among all stakeholders (athlete, medical team, coaching staff). She should also implement neuromuscular exercises (eg core/hip stabilization, reactive stabilization drills for the lower extremity, …) in her warm-up routine, in terms of secondary prevention.41 Eventually, and if the athlete asks for, she could benefit from the professional help of a sport psychologist/mental health practitioner during the RTS/return to performance process.42

From a Sports Psychiatrist

The total ACL-RSI and each of the subscales are scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing greater psychological readiness to return to sport.43 Various thresholds have been implemented, but multiple studies have suggested that total scores less than 56 to 62 points are associated with increased difficulty returning to one’s previous level of sport participation.37,44,45 One study found that the risk appraisal subscale took the longest to improve after ACLR and had a significant impact on the ability for athletes to return to sports.46 This patient scored relatively low on the overall score as well as the subscales, suggesting that early implementation of psychological interventions would likely be helpful. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in particular could be beneficial to target maladaptive thought patterns or emotional factors, both of which could significantly impact the likelihood of successful RTS.

It is important to recognize that sport-related injuries can be traumatic for young athletes and may be associated with psychological responses similar to those seen with post-traumatic stress. Given the prolonged nature of recovery after ACLR and the rigorous rehabilitation required to return to sports, sustaining an ACL tear can be devastating for an athlete. This is particularly true for athletes sustaining a second ACL tear (whether contralateral ACL or ipsilateral/graft tear), after having already overcome the myriad physical and psychological challenges associated with this type of injury. While many athletes undergoing ACLR might benefit from formal psychological treatment such as CBT, all sports medicine and allied health providers can participate in supporting the mental health of these athletes by simply asking how they are doing emotionally throughout the entire course of recovery, validating their experiences, encouraging help-seeking behaviors, and providing support when needed.

From a Clinical Physical Therapist

Given that this injury is this patient’s second lifetime ACL injury, we must take caution in her RTS progression. As discussed previously, the familiarity this patient has with the rehabilitation process could promote a swifter progression through her rehabilitation. Therefore, it is the duty of her rehabilitation team to ensure she is reaching the milestones set at each stage and moving along with appropriate pace. In looking at the RTS process as a continuum as originally proposed by Ardern and other physical therapy experts as a consensus statement47 and later discussed by Meredith et al48 . The process of “return to sport” can be broken down into three parts: “return to participation”, “return to sport”, and “return to performance”, and step-by-step return to approach is clinically feasible (Figure 1). While she currently does not achieve a 10% threshold in LSI scores of both strength and hop tests, the “return to participation” phase is ideal step for her at this time. “Return to participation” is defined as a return to training below the level at which she had been participating in sport prior to her injury. This type of training can include activities that she would not be participating in with her teammates such as non-contact cutting and pivoting drills. She could start in a highly controlled environment and gradually progress to a more challenging environment, simulating more team practice-oriented environments.

|

Figure 1 Step-by-Step Return Approach Model.

|

In deciding on when to progress her to the “return to sport” phase of training, she should perform the battery of hop testing and strength testing as she has been tested with these measures previously and progress can be objectively tracked with these measures. However, in agreement with other clinicians, these tests should not be the only measures to consider in her RTS testing as she has had previous ACLR surgery on her contralateral limb, affecting the comparison of each limb. Quality of her movement patterns during plyometric and cutting/pivoting drills should be considered as well. Once the patient has achieved strength and hop testing within 10% and she has demonstrated improvement in her movement patterns, she can progress to the “return to sport” phase in which she would gradually integrate into her team practices, but not at the desired level of performance. This phase begins progressing from non-contact drills, to contact drills, then game-like scrimmages and finally a return to competitive play. During this progression, the rehabilitation team would be checking in with the athlete to monitor for signs of diminished strength, ROM, or pain as indicators as to whether or not she can continue the progression. Finally, she would enter the “return to performance” phase. In this phase, she would continue to progress her strength, agility, and sport-specific functional skillsets, ideally with a strength and conditioning specialist/fitness coach, to progress towards pre-injury levels of play. This can be the longest phase of the RTS process as it can last one to two years past her ACLR surgical date.

A continuum-based approach to the RTS process can be highly beneficial for the athlete for a variety of reasons. It encourages the athlete and rehabilitation team to have ongoing evaluations upwards of two years past the surgical date to assess for any deficits of strength, pain, ROM and psychological readiness for sport. This athlete, in particular, does demonstrate through her psychological readiness testing that she does have apprehension for RTS; therefore, a stepwise progression of RTS approach may be feasible to improve her confidence in her sport as she advances through her phases of RTS. Further, this stepwise approach likely facilitates professional communications among the athlete/patient, rehabilitation therapists, and coaching staff members. One important aspect of this stepwise approach is to establish clear goals in each phase. Finally, in looking at the RTS as a continuum, the athlete could progress or regress depending on her responses to each goal that she achieves in her journey back to sport.

From a Performance and Sport Scientist

This young female basketball player still demonstrated inadequate LSI values in peak muscle torque of quadriceps (82%) and hamstring (86%) as well as single leg hop tests (ranges from 72% to 84%), and it is concerning. Several articles suggested ≥90% of the LSI for safe RTS.26,49 One of the studies reported 84% of quadriceps LSI values in no ACL re-injury group compared to 75% in re-injured group at the time of RTS following ACLR.50 One good news is her H/Q ratio. Her H/Q ratio was 58%, which may be clinically sufficient. One documented evidence showed H/Q ratio of 58% in concentric muscle contraction at angular speed 60°/s did not have ACL graft rupture while those who sustained a graft rupture showed H/Q ratio of 53% after ACLR.51 The hamstring muscles are considered to take a protective role as an agonist to ACL by resisting the anterior tibial displacement that results from quadriceps muscle forces at the knee.51 Thus, although she showed an acceptable H/Q ratio at this point, I encourage her to keep strengthening hamstring muscles.

To facilitate a safe RTS for her, we need to understand unique features of basketball. Female basketball players typically cover a total of 5214 ± 315 meters with 576 ± 110 movement changes in a match.52 Also, basketball players alter their movement patterns every 1–3 seconds during a match while spending approximately 34% of their time in running and jumping activities.53,54 Understanding those basketball-specific movement characteristics is beneficial to develop a sport-specific rehabilitation program and likely helps facilitate a safe RTS progression. Moreover, optimizing the load progression with respect to her basketball level (eg college, recreational, or professional), specific position (eg center, forward, or guard), and ideal timing (eg during a regular season, off-season, or perhaps, pre-season) need to be considered. During the on-court phase of the RTS, it is crucial to optimize her physical load (eg base on principle of progressive overload) with aim of avoiding rapid spikes in her training.55 Also, not only her physical load control, her mental fitness/health in relation to on-court phase of the RTS process need to be monitored. Recent studies showed lower psychological readiness in RTS in females compared to males.56,57 In short, in the on-court phase of the RTS process, a clinical practitioner such as athletic trainer, fitness coach, and strength and conditioning specialist needs to implement a sport-specific rehabilitation, control workload, and pay attention to psychological/mental status.

One of the recent RTS frameworks respecting specific sport content is called a control-chaos continuum (CCC), which was originally designed for on-pitch rehabilitation in elite soccer58 and later adapted also on basketball.39 Briefly, the CCC principle described importance of gym-based physical preparation and on-court rehabilitation, which are progressing from high control training stimuli, through moderate control, control to chaos, moderate chaos and finally high chaos stimuli/conditions.39 During the last stage (the high chaos stimuli/conditions phase), athlete should be able to reach >90% maximal running speed, positional specific acceleration, repeated change of directions with adequate speed and without pain, and specific jump-landing actions (eg shooting, rebounding, and blocking). Those sport-specific drills need to be carefully performed and progressed with qualified clinical practitioners in relation to the athlete’s overall physical (eg pain) and mental (eg fear) states.

Discussion

The purpose of the current commentary was to discuss how to optimize a safe RTS following ACLR based on clinical perspectives from various sports medicine healthcare practitioners and also to synthesize their recommendations with research evidence. In this case, the young female basketball player had two ACLR surgeries, one in each limb. As the orthopaedic surgeon and academic-physiotherapist were concerned, it would not be reliable to use the LSI as a mean of the RTS because the reference knee for the LSI (her right knee) had a previous ACLR surgery 4 years prior. Even though the initial surgery was 4 years ago, it may alter the LSI values, possibly inflating the LSI values of her left knee since the right knee may not be 100%. So, what would be a good way to evaluate a safe RTS in this scenario? As suggested by the performance and sport scientist, H/Q ratio may be an option. It was evidenced that higher H/Q ratio (higher hamstring strength in relation to quadriceps strength) is protective to initial ACL tear59 and graft re-tear.51 This approach does not require another limb as a reference, however it may be deceiving in a case where quadriceps strength is significantly impacted resulting in a higher ratio, rather than higher hamstring strength driving the improvement in this metric. Alternatively, according to the academic-physiotherapist, peak torque/body weight values were reported in the past study31 and may be an option. In this study, isokinetic strength (60 deg/sec, 180 deg/sec, and 300 deg/sec) of the quadriceps and hamstrings were presented in elite and nonelite of female basketball players.31 If an isokinetic machine is available, one study reported age-, sex-, and graft used in ACLR-specific quadriceps and hamstrings strength values,60 and using the reported data as a reference may be another useful approach. Additionally, the academic-physiotherapist suggested including neurocognitive load evaluation in RTS. Incorporating neurocognitive load in rehabilitation is a fairly new idea. Several recent studies suggested assessing neurocognitive and neurophysiological functions for those who have a torn ACL.61–64 One of the articles discussed importance of re-acquisition of motor skills and training of neuroplastic capacities during rehabilitation, which may potentially help reducing subsequent ACL injury.61,62 In short, the concept of the neurocognitive load into rehabilitation and possibly RTS tests is emerging, and more evidence is necessary; however, this may be beneficial for the current scenario, if the theory is that neurocognitive deficits in this athlete may have contributed to the increased risk of ACL injury.

Another major concern voiced by multiple experts was low ACL-RSI scores presented at 9 months following ACLR surgery. The low ACL-RSI scores may be due to this being her second time sustaining an ACL tear. A sports psychiatrist pointed out that the ACL-RSI score ranges of 56–62 are associated with difficult to reach previous level of athletic participation. One study found that the ACL-RSI score was lower at 12 months following ACLR for those who resulted in second ACL injury among 20 years or younger.65 The reported mean ACL-RSI scores of those who sustained the second ACL injury at 12 months in this study was 60.8.65 The sports psychiatrist suggested the use of CBT to help psychological state of this young female basketball player. CBT has been commonly prescribed to treat anxiety and depression,66–68 but there has been only one study related to CBT intervention to ACL patients.69 In this study, young athletes who had ACLR surgery had a telephone-based cognitive-behavioral based physical therapy intervention for 8 weeks.69 At 6 months, all patients who completed this intervention demonstrated meaningful change measured by minimal clinically important difference (MCID) on International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), sport/recreation and quality of life subscales of Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK).69 Since only one study was documented, and the title of this study was a pilot study,69 more evidence is necessary, especially how the CBT-based intervention affects ACL-RSI scores and subsequent ACL injury risk. Additionally, a few studies found that female athletes tend to demonstrate lower ACL-RSI scores compared to their male counterparts.56,57 Therefore, psychological intervention may need to be targeted to female athletes more than male athletes.

The clinical physical therapist presented a step-by-step RTS approach, which consists of “return to participation”, “return to sport”, and “return to performance”.48 In this article, the “return to participation” consisted of two specific components: progression to unrestricted training and clearance to full participation.48 In this case, the young female basketball player did not reach to previously advocated, commonly used less than 10% of deficits in many RTS tests,26 she is still in this phase (progression to unrestricted training). A similar concept was presented in other articles, which broke down the safe RTS to the following 4 phases: 1) on-field rehabilitation, 2) return to training, 3) return to competitive match play, and 4) return to play.70,71 One of the articles emphasized to focus on restoring movement quality, physical conditioning, and sport-specific skills during the on-field rehabilitation phase.71 Furthermore, this article highlighted importance of progressive loading during this phase. Synthesizing these suggestions into progression to unrestricted training in “return to participation” phase based on this case, this young female athlete should practice various drills in a controlled environment with emphasis of movement quality, physical conditioning and sport-specific skills under appropriate, progressive loads. Sport-specific drills (in this scenario basketball) can be found in an article titled “Suggestions from the field for RTS participation following ACLR: Basketball”.39 During this phase, managing pain, swelling, and any other clinical symptoms that may be a reflection of the last phase of this rehabilitation are necessary,72 and clinician(s) need to have a good communication with the athlete. After this the initial stage (return to participation), “return to sport” and “return to performance” are the next two steps.48 In these phases, reconditioning could be another challenging aspect. The reconditioning could be defined as “re-establishing and/or improving an athlete’s overall physical fitness after an injury or surgery”.73 One study identified diminished aerobic capacity quantified by VO2max followed by ACLR in relation to a matched healthy control.74 In addition to the aerobic fitness, the final stage of the RTS needs to simulate a real game/competition-like situation. Visual-spatial, decision-making, and perturbation training are recommended.73 Using perturbation training as an example, the perturbation needs to be simulated by specific position(s) of the athlete and specific movement(s) the athlete commonly performs in conjunction with how opponent(s) tends to move, and potentially with physical perturbance/pressure. Lastly, commented by the performance and sport scientist, the rehabilitation and the RTS process should be performed in relation to the context of the sport each athlete is hoping to return including level, position, and timing. Recent studies highlighted importance of controlling workload55 and challenges associated with the work load (eg levels of chaos in the RTS continuum).39,58 A medical team member such as athletic trainer, fitness coach, and strength and conditioning specialist, if available, should play a major role for bridging the post-RTS to the “return-to-performance”.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this article. Firstly, this article was not written based on actual study or experiment performed. Therefore, the concepts written in this article need a validation. Secondly, this article was a synthesis of experts’ opinions and existing literature, not a systematic review; thus, evidence level is low. Lastly, experts’ input was presented in one clinical scenario. Each ACL injury and re-tear clinical case and scenario is unique; therefore, the generatability of this article is limited to young athletes who are willing to return to competitive sports.

Conclusion

In this article, several important ideas were discussed by various sports medicine healthcare practitioners and synthesized with recent research findings to facilitate the safe RTS following ALCR using a scenario. Collectively, the professional recommended incorporating neurocognitive load into rehabilitation, psychological interventions such as CBT, and a step-by-step RTS approach as emerging concepts for young athletes. Even after the RTS test, on-site clinicians need to control the appropriate workload of each athlete in this chaotic returning continuum. More empirical research studies are necessary to substantiate the voices from the experts in this article, which may help reduce unfortunate another tear following primary ACLR surgery among young athletes.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

All authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. All authors have no financial issues related to the current manuscript. The clinical scenario used in the current article is a fictional case.

References

1. Blair SN, Kohl HW, Gordon NF, Paffenbarger RS Jr. How much physical activity is good for health? Ann Rev Public Health. 1992;13:99–126. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.13.050192.000531

2. Bauman A, Owen N. Physical activity of adult Australians: epidemiological evidence and potential strategies for health gain. J Sci Med Sport. 1999;2(1):30–41. doi:10.1016/S1440-2440(99)80182-0

3. Malm C, Jakobsson J, Isaksson A. Physical activity and sports-real health benefits: a review with insight into the public health of Sweden. Sports. 2019;7(5):127. doi:10.3390/sports7050127

4. Lloyd RS, Oliver JL, Faigenbaum AD, et al. Long-term athletic development- part 1: a pathway for all youth. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2015;29(5):1439–1450. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000756

5. Comstock RD, Knox C, Yard E, Gilchrist J. Sports-related injuries among high school athletes–United States, 2005-06 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(38):1037–1040.

6. Malekpour M-R, Rezaei N, Azadnajafabad S. Global, regional, and national burden of injuries, and burden attributable to injuries risk factors, 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Public Health. 2024;237:212–231. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2024.06.011

7. Nippert AH, Smith AM. Psychologic stress related to injury and impact on sport performance. Phys Med Rehab Clin North Am. 2008;19(2):399–418, x. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2007.12.003

8. Haraldsdottir K, Watson AM. Psychosocial impacts of sports-related injuries in adolescent athletes. Current Sports Med Rep. 2021;20(2):104–108. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000809

9. Mosler AB, Carey DL, Thorborg K, et al. In professional male soccer players, time-loss groin injury is more associated with the team played for than with training/match-play duration. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2022;52(4):217–223. doi:10.2519/jospt.2022.10845

10. Mendes-Cunha S, Moita JP, Xarez L, Torres J. Dance-related musculoskeletal injury leading to forced time-loss in elite pre professional dancers – a retrospective study. Physic Sports Med. 2023;51(5):449–457. doi:10.1080/00913847.2022.2129503

11. Eliakim E, Morgulev E, Lidor R, Meckel Y. Estimation of injury costs: financial damage of English Premier League teams’ underachievement due to injuries. BMJ Open Sport Exercise Med. 2020;6(1):e000675. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000675

12. Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Paterno MV, Quatman CE. Mechanisms, prediction, and prevention of ACL injuries: cut risk with three sharpened and validated tools. J Orthopaedic Res. 2016;34(11):1843–1855. doi:10.1002/jor.23414

13. Mancino F, Kayani B, Gabr A, Fontalis A, Plastow R, Haddad FS. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: risk factors and strategies for prevention. Bone Joint Open. 2024;5(2):94–100. doi:10.1302/2633-1462.52.BJO-2023-0166

14. Arendt EA, Agel J, Dick R. Anterior cruciate ligament injury patterns among collegiate men and women. J Athletic Train. 1999;34(2):86–92.

15. Jin H, Tahir N, Jiang S, et al. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Sports Med Open. 2025;11(1):40. doi:10.1186/s40798-025-00844-7

16. Cavanaugh JT, Powers M. ACL rehabilitation progression: where are we now? Current Rev Musculoskel Med. 2017;10(3):289–296. doi:10.1007/s12178-017-9426-3

17. Golberg E, Sommerfeldt M, Pinkoski A, Dennett L, Beaupre L. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction return-to-sport decision-making: a scoping review. Sports Health. 2024;16(1):115–123. doi:10.1177/19417381221147524

18. Sugimoto D, Heyworth BE, Carpenito SC, Davis FW, Kocher MS, Micheli LJ. Low proportion of skeletally immature patients met return-to-sports criteria at 7 months following ACL reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2020;44:143–150. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.05.007

19. Sugimoto D, Milewski MD, Williams KA, et al. Effect of age and sex on anterior cruciate ligament functional tests approximately 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy Sports Med Rehab. 2024;6(3):100897. doi:10.1016/j.asmr.2024.100897

20. Gokeler A, Dingenen B, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation and return to sport testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: where are we in 2022? Arthroscopy Sports Med Rehab. 2022;4(1):e77–e82. doi:10.1016/j.asmr.2021.10.025

21. Maguire K, Sugimoto D, Micheli LJ, Kocher MS, Heyworth BE. Recovery after ACL reconstruction in male versus female adolescents: a matched, sex-based cohort analysis of 543 patients. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2021;9(11):23259671211054804. doi:10.1177/23259671211054804

22. Sugimoto D, Heyworth BE, Brodeur JJ, Kramer DE, Kocher MS, Micheli LJ. Effect of graft type on balance and hop tests in adolescent males following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Sport Rehab. 2019;28(5):468–475. doi:10.1123/jsr.2017-0244

23. Webster KE, Feller JA. Evaluation of the responsiveness of the anterior cruciate ligament return to sport after injury (ACL-RSI) scale. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2021;9(8):23259671211031240. doi:10.1177/23259671211031240

24. Webster KE, Feller JA. Psychological readiness to return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the adolescent athlete. J Athletic Train. 2022;57(9–10):955–960. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-0543.21

25. Lorange JP, Senécal L, Moisan P, Nault ML. Return to sport after pediatric anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of the criteria. Am J Sports Med. 2024;52(6):1641–1651. doi:10.1177/03635465231187039

26. Adams D, Logerstedt DS, Hunter-Giordano A, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(7):601–614. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.3871

27. Zhou W, Liu X, Hong Q, Wang J, Luo X. Association between passing return-to-sport testing and re-injury risk in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2024;12:e17279. doi:10.7717/peerj.17279

28. Losciale JM, Zdeb RM, Ledbetter L, Reiman MP, Sell TC. The association between passing return-to-sport criteria and second anterior cruciate ligament injury risk: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(2):43–54. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8190

29. Gill VS, Tummala SV, Sullivan G, et al. Functional return-to-sport testing demonstrates inconsistency in predicting short-term outcomes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2024;40(7):2135–2151.e2132. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2023.12.032

30. Gifstad T, Drogset JO, Viset A, Grøntvedt T, Hortemo GS. Inferior results after revision ACL reconstructions: a comparison with primary ACL reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol arthroscopy. 2013;21(9):2011–2018. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2336-4

31. van Melick N, van der Weegen W, van der Horst N. Quadriceps and hamstrings strength reference values for athletes with and without anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction who play popular pivoting sports, including soccer, basketball, and handball: a scoping review. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2022;52(3):142–155. doi:10.2519/jospt.2022.10693

32. Bizzini M, Silvers HJ. Return to competitive football after major knee surgery: more questions than answers? J Sports Sci. 2014;32(13):1209–1216. doi:10.1080/02640414.2014.909603

33. Grooms DR, Chaput M, Simon JE, Criss CR, Myer GD, Diekfuss JA. Combining neurocognitive and functional tests to improve return-to-sport decisions following ACL reconstruction. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(8):415–419. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.11489

34. Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders A, et al. 2016 consensus statement on return to sport from the first world congress in sports physical therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(14):853–864. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096278

35. Meredith SJ, Rauer T, Chmielewski TL, et al. Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: panther symposium ACL injury return to sport consensus group. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2020;8(6):2325967120930829. doi:10.1177/2325967120930829

36. Webster KE, McPherson AL, Hewett TE, Feller JA. Factors associated with a return to preinjury level of sport performance after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(11):2557–2562. doi:10.1177/0363546519865537

37. Sadeqi M, Klouche S, Bohu Y, Herman S, Lefevre N, Gerometta A. Progression of the psychological ACL-RSI score and return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective 2-year follow-up study from the french prospective anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction cohort study (FAST). Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2018;6(12):2325967118812819. doi:10.1177/2325967118812819

38. Waters E. Suggestions from the field for return to sports participation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: basketball. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):326–336. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.4030

39. Taberner M, Spencer N, Murphy B, Antflick J, Cohen DD. Progressing on-court rehabilitation after injury: the control-chaos continuum adapted to basketball. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(9):498–509. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.11981

40. Welling W. Return to sports after an ACL reconstruction in 2024 – A glass half full? A narrative review. Phys Ther Sport. 2024;67:141–148. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2024.05.001

41. Di Stasi S, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training to target deficits associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(11):777–792, a771–711. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.4693

42. Forsdyke D, Gledhill A, Ardern C. Psychological readiness to return to sport: three key elements to help the practitioner decide whether the athlete is REALLY ready? Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(7):555–556. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096770

43. Webster KE, Feller JA. Development and validation of a short version of the anterior cruciate ligament return to sport after injury (ACL-RSI) scale. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2018;6(4):2325967118763763. doi:10.1177/2325967118763763

44. Faleide AGH, Inderhaug E. It is time to target psychological readiness (or lack of readiness) in return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament tears. J Exp Orthopaedics. 2023;10(1):94. doi:10.1186/s40634-023-00657-1

45. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Whitehead TS, Webster KE. Psychological responses matter in returning to preinjury level of sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1549–1558. doi:10.1177/0363546513489284

46. Kim Y, Kubota M, Sato T, Inui T, Ohno R, Ishijima M. Psychological patient-reported outcome measure after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: evaluation of subcategory in ACL-return to sport after injury (ACL-RSI) scale. Orthopaedics Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108(3):103141. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2021.103141

47. Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders AG, et al. Infographic: 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the first world congress in sports physical therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(13):995. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097468

48. Meredith SJ, Rauer T, Chmielewski TL, et al. Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: panther symposium ACL injury return to sport consensus group. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(8):2403–2414. doi:10.1007/s00167-020-06009-1

49. Dingenen B, Gokeler A. Optimization of the return-to-sport paradigm after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a critical step back to move forward. Sports Med. 2017;47(8):1487–1500. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0674-6

50. Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(13):804–808. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031

51. Kyritsis P, Bahr R, Landreau P, Miladi R, Witvrouw E. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(15):946–951. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095908

52. Scanlan AT, Dascombe BJ, Reaburn P, Dalbo VJ. The physiological and activity demands experienced by Australian female basketball players during competition. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15(4):341–347. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2011.12.008

53. Narazaki K, Berg K, Stergiou N, Chen B. Physiological demands of competitive basketball. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(3):425–432. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00789.x

54. Ostojic SM, Mazic S, Dikic N. Profiling in basketball: physical and physiological characteristics of elite players. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2006;20(4):740–744. doi:10.1519/R-15944.1

55. Blanch P, Gabbett TJ. Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute: chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(8):471–475. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095445

56. Milewski MD, Traver JL, Coene RP, et al. Effect of age and sex on psychological readiness and patient-reported outcomes 6 months after primary ACL reconstruction. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2023;11(6):23259671231166012. doi:10.1177/23259671231166012

57. Obradovic A, Manojlovic M, Rajcic A, et al. Males have higher psychological readiness to return to sports than females after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exercise Med. 2024;10(4):e001996. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2024-001996

58. Taberner M, Allen T, Cohen DD. Progressing rehabilitation after injury: consider the ‘control-chaos continuum’. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(18):1132–1136. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100157

59. Myer GD, Ford KR, Barber Foss KD, Liu C, Nick TG, Hewett TE. The relationship of hamstrings and quadriceps strength to anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19(1):3–8. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e318190bddb

60. Kuenze C, Weaver A, Grindstaff TL, et al. Age-, sex-, and graft-specific reference values from 783 adolescent patients at 5 to 7 months after ACL reconstruction: IKDC, Pedi-IKDC, KOOS, ACL-RSI, single-leg hop, and thigh strength. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(4):194–201. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.11389

61. Gokeler A, Neuhaus D, Benjaminse A, Grooms DR, Baumeister J. Correction to: principles of motor learning to support neuroplasticity after ACL injury: implications for optimizing performance and reducing risk of second ACL injury. Sports Med. 2019;49(6):979. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01078-w

62. Gokeler A, Neuhaus D, Benjaminse A, Grooms DR, Baumeister J. Principles of motor learning to support neuroplasticity after ACL injury: implications for optimizing performance and reducing risk of second ACL injury. Sports Med. 2019;49(6):853–865. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01058-0

63. Chaput M, Criss CR, Onate JA, Simon JE, Grooms DR. Neural activity for uninvolved knee motor control after ACL reconstruction differs from healthy controls. Brain Sci. 2025;15(2):109. doi:10.3390/brainsci15020109

64. An YW, Lobacz AD, Baumeister J, et al. Negative emotion and joint-stiffness regulation strategies after anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Athletic Train. 2019;54(12):1269–1279. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-246-18

65. McPherson AL, Feller JA, Hewett TE, Webster KE. Psychological readiness to return to sport is associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(4):857–862. doi:10.1177/0363546518825258

66. Apolinário-Hagen J, Drüge M, Fritsche L. Cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance commitment therapy for anxiety disorders: integrating traditional with digital treatment approaches. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:291–329.

67. Lee SH, Cho SJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depressive disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1305:295–310.

68. Oar EL, Johnco C, Ollendick TH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):661–674. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.002

69. Coronado RA, Sterling EK, Fenster DE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral-based physical therapy to enhance return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an open pilot study. Phys Ther Sport. 2020;42:82–90. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.01.004

70. Buckthorpe M, Frizziero A, Roi GS. Update on functional recovery process for the injured athlete: return to sport continuum redefined. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(5):265–267. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099341

71. Buckthorpe M, Della Villa F, Della Villa S, Roi GS. On-field rehabilitation part 1: 4 pillars of high-quality on-field rehabilitation are restoring movement quality, physical conditioning, restoring sport-specific skills, and progressively developing chronic training load. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):565–569. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8954

72. Buckthorpe M, Della Villa F, Della Villa S, Roi GS. On-field rehabilitation part 2: a 5-stage program for the soccer player focused on linear movements, multidirectional movements, soccer-specific skills, soccer-specific movements, and modified practice. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):570–575. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8952

73. Gokeler A, Grassi A, Hoogeslag R, et al. Return to sports after ACL injury 5 years from now: 10 things we must do. J Exp Orthopaedics. 2022;9(1):73. doi:10.1186/s40634-022-00514-7

74. Slater LV, Hart JM. Quantifying the relationship between quadriceps strength and aerobic fitness following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2022;55:106–110. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2022.03.005

Rec Sports

Youth Sports Was 2025’s Breakout M&A Theme. Here’s What’s Next

Today’s guest columnist is Chris Russo, CEO of Fifth Generation Sports.

In the world of sports mergers and acquisitions, 2025 was the year of youth sports. What had long been a fragmented, passion-driven corner of the sports economy became one of the most active segments for investors and strategic acquirers.

Numerous acquisitions closed across software, events, media and facility operations. Many private equity firms, some of which had never made sports-related investments, “discovered” youth sports as a scalable, high growth opportunity.

The result was a surge of deal volume, valuations and heightened competition for quality assets. But the youth sports boom was not a one-year anomaly. It’s become one of the hottest M&A categories, driven by structural factors that continue to reshape the industry:

1. Scale of the market

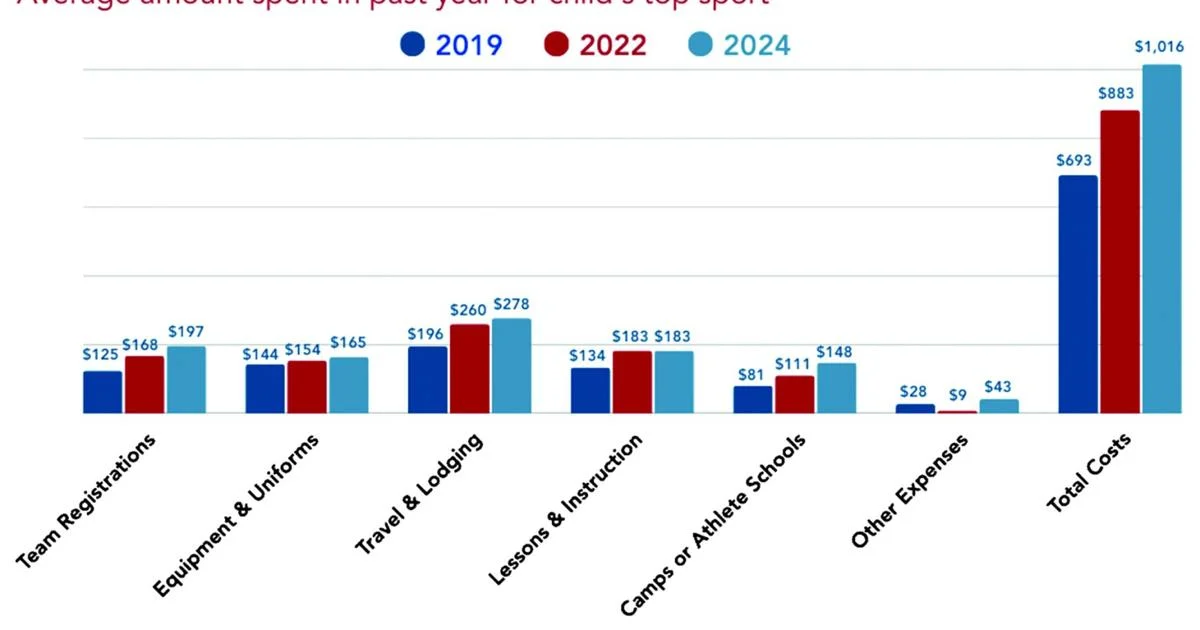

Youth sports is now a $40+ billion economic engine, including registration fees, equipment and uniforms, travel and lodging, and lessons and instruction, among other expenditures charted by the Aspen Institute. These products and services are targeted to approximately 27 million kids aged 6-17 who play organized sports in the U.S. The sheer size of this total addressable market (TAM) makes it an attractive sector for acquirers.

2. Extreme fragmentation across verticals

Youth sports remains extraordinarily fragmented with thousands of independent clubs, hundreds of regional tournament operators, dozens of niche software or video-analysis providers, and event companies with highly localized or sports specific reach. But beyond simple fragmentation, many of these operators are historically “mom and pop” run without standardized operations or scalable infrastructure. For private equity, this represents a double opportunity, for roll-up synergies (shared services, procurement, marketing, cross-selling, branding) and professionalization upside (opportunity to enhance margins and performance once modern systems and management discipline are introduced). Buyers recognize that even modest consolidation may create meaningful value when replicated across dozens or hundreds of locations or events.

3. Parent spending and the emergence of NIL

Youth sports spending has long been resilient as families prioritize team fees, tournament travel, private coaching and club participation over many other expenses. But in recent years, the rise of NIL has raised the stakes and accelerated this trend, helping to drive a 46% increase in average family spending on each child’s primary sport since 2019, according to the Aspen Institute. The ability for college athletes to earn name, image and likeness (NIL) income has fundamentally changed the psychology of many parents. While only a small percentage of athletes will ever play in college, a much larger percentage of families believe they might, or at minimum, believe their child has a shot at scholarship or NIL-related opportunities. This belief system—whether realistic or aspirational—has driven even greater investment in club teams and travel tournaments, showcases, personal training, recruiting platforms and video analysis.

4. Development of new products and services

The past five years have seen an explosion in new monetizable products and services that have expanded the youth-sports wallet. COVID accelerated video streaming, enabling live event subscription, remote instruction and enhanced digital recruiting. Technology and AI are now transforming performance and training, including AI-driven highlights, player tracking, advanced analytics and data aggregation, and biometric tools. These tech and software innovations have also created new recurring-revenue business models that may scale more efficiently than clubs or facilities. Some investors see this as a structural tailwind that will last for years.

5. Entrance of respected investors and buyers

Perhaps the most important accelerant in 2025 was the entry of highly credible investors—PE firms, family offices, pro-team owners and sports-focused funds—who validated the category. This process had actually begun a few years earlier in 2022 when KKR invested in PlayOn. Then in 2024 and 2025, Josh Harris and David Blitzer—owners of the Philadelphia 76ers, New Jersey Devils and other pro sports properties—publicly and aggressively entered youth sports through the creation of Unrivaled Sports.

The Harris Blitzer initiative was featured in a widely circulated New York Times article published in July, a watershed moment for the industry. The piece validated youth sports as a legitimate, investable asset class, signaled that major sports owners were now committed to the sector, and inspired a wave of new entrants (family offices, PE and institutional capital).

As the youth sports investment wave matures, investors and operators will be focused on three defining questions:

1. Are there enough scaled assets?

The biggest constraint in youth sports has always been a lack of scaled properties to sustain deal momentum. Many clubs, events and platforms are sub-$5M EBITDA businesses, and a question remains as to whether there are enough $5M+ EBITDA assets to keep institutional buyers active.

2. Will robust valuations continue?

2025 saw elevated multiples for top-tier assets, driven in part by competition from first-time PE entrants. The sustainability of valuations in 2026 may hinge on supply/demand imbalances for quality companies, platform performance and integration success of recently completed deals, and overall economic factors (e.g. interest rate trends and the cost of debt).

3. Which sectors will attract the most investment and buyer interest?

Several youth sports verticals appear best positioned for 2026 activity, including facilities, events, video streaming and software products, especially for performance and training. However, there is also the possibility that other categories (e.g., e-commerce or traditional categories such as equipment and apparel) could emerge as high growth opportunities over the next 12 months.

This much is clear. The youth sports boom of 2025 was not a temporary spike—it was the formal institutionalization of an asset class long overlooked. Structural drivers remain intact, respected investors are now committed, and an emerging ecosystem of scaled operators is taking shape. The next year will test whether the sector can keep pace, but many indicators suggest youth sports could remain one of the most dynamic and investable categories within the sports economy for years to come.

Chris Russo is CEO of Fifth Generation Sports, a boutique advisory firm focused on middle market sports transactions. He advised SportsRecruits and Big Teams on the deals listed above. Previously, Russo served as a managing director at Houlihan Lokey, and before his tenure in investment banking, he managed the NFL’s digital media group. Russo holds a B.A. from Northwestern University and an MBA from the Harvard Business School.

Rec Sports

Santa Barbara Volleyball Club to Build New Indoor Facility

Santa Barbara Volleyball Club announced plans for a dedicated youth sports facility and indoor gym, which is slated to be built on property leased from the County of Santa Barbara on Hollister Avenue.

The new gym is in the planning stages, following the approval of the lease by the County Board of Supervisors earlier this week. The project is intended to tackle a shortage of indoor space for youth sports and allow the Santa Barbara Volleyball and similar organizations to keep expanding access for youth sports activities.

“This is a wonderful example of how the county can partner with local organizations to expand opportunities for young people,” Supervisor Laura Capps said. “By investing in youth sports and creating spaces where kids can learn teamwork, confidence, and resilience, we’re strengthening the fabric of our community for years to come.”

Santa Barbara Volleyball Club Executive Director Matt Riley said the project represents “a major investment in the future of youth sports in Santa Barbara.” With the dedicated space, the club can increase programming, stop relying on outside facilities, and welcome other sports leagues to use the gym.

“Our goal is to create a safe, high-quality environment where young athletes can develop not only as volleyball players, but as teammates, leaders, and community members,” Riley said.

Riley said Santa Barbara Volleyball Club appreciated the county’s willingness to work in collaboration to make the project a reality. The county and the club will continue to work together to guide the project through planning review and permitting.

The property on Hollister Avenue is next door to another development, a 34-unit housing development made in another collaboration between the county and the Housing Authority. The housing project, dedicated to service formerly homeless tenants, broke ground just last week.

The new Santa Barbara Volleyball Club facility will be primarily funded through grants and private donations. More information will be provided on the club’s website (santabarbaravolleyballclub.com).

Rec Sports

Arizona youth sports’ cost rises steadily for parents | Sports

As the cost of youth sports continues to rise, families across Arizona are being priced out of participation.

From local clubs to travel teams, the expenses add up with equipment, uniforms, tournament fees and more totaling thousands of dollars annually, putting pressure on families and widening the gap between those who can afford to play and those who can’t.

The financial strain is reshaping who gets to participate, raising concerns among researchers, nonprofits and parents about long-term access and equity.

According to a 2023 study by the Aspen Institute’s Project Play, Arizona ranked second to last in the country for youth ages 6-17 who played on a team or took lessons.

Less than half of high school students reported playing on one or more sports teams during the past 12 months according to research done by the Arizona Department of Health Services Bureau of Nutrition and Physical Activity.

“Costs are rising and as a result of that we are seeing lower rates of participation, particularly in under-resourced, traditionally underrepresented communities,” said Eric Legg, assistant professor in Arizona State University’s School of Community Resources & Development.

“It’s a wrecked relationship,” he said. “Costs go up, participation goes down, and it most impacts underrepresented communities.”

Youth sports play a crucial role in children’s development, allowing for positive social, emotional and physical growth.

The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) found that physical activity enhances self-perceptions of body, competence and self-worth and that playing a sport can even protect against suicide risk in youth.

At the Boys & Girls Club of the Valley (BGCAZ), the importance of youth development is embedded in their subsidized sports, fitness and recreation programs.

“Unfortunately, as kids have started to specialize in sports, they’re dropping out of sport at a younger and younger age,” said Josh Stine, BGCAZ vice president of external affairs.

“Our goal is to keep [them] playing sports longer. We want you to play for the health benefits, for the social recreation, for the communication skills you build.”

In the past year, the average amount AZ families spent on all their children’s sports programs was just short of $1500.

Rising costs for both families and organizations like BGCAZ affect equipment, staffing and facility rentals.

Project Play found that the average U.S. sports family spent $1,016 on a child’s primary sport in 2024. This is a 46% increase from 2019, twice the rate of price inflation in the U.S. economy during the same period.

Some companies and organizations are trying to fill the financial gaps for these families.

“Our corporate partners and our community partners are able to provide access to equipment and uniforms at a lower cost or donated so kids have access,” Stine said. “We don’t want a kid not playing or not signing up because they don’t have the proper shoes or the glove.

“It’s really trying to lean into our partners where we can to help cover the costs that were traditionally passed on to our students or players.”

Local government has been an option, but Legg said a major issue is the massive reduction in how much local governments invest in youth sports.

Legg said that youth sports programs were at one point primarily subsidized by tax dollars and community support. This practice has shifted as the more commonly used funding model is the “pay to play” model, where the program is supported by participant fees.

“Youth sports create healthy youth, healthy youth create healthy communities,” Legg said. “It’s actually a cost saver in the long term and investing more in those communities through tax dollar support.”

The “pay to play” model is just one of the effects of the rapid commercialization of youth sports. This commercialization is prominent in the increase in club sports, programs that are run by private associations and often have much higher fees than traditional school or nonprofit youth sports programs.

For many families, cost is often the most important factor when considering youth sports programs.

Nick Girard, father of two and current president of Recreation Association of Madison Meadows & Simis (RAMMS), said cost is something he and many other parents weigh thoroughly.

“From the parents’ standpoint, I see that [rising cost] when I pay the registration fees, in RAMMS recreational sports and club sports,” Girard said. “I have kids who do club sports so I see all aspects of this.”

Not surprisingly, the money parents pay for a child to participate in a primary sport and other sports along the way in one year varies with the child’s age.

RAMMS is a parent-run, volunteer-led nonprofit that provides recreational youth sports for children in North Central Phoenix. Like BGCAZ and similar nonprofits, it relies on registration fees and sponsorships to fund venues, uniforms, equipment and improvements to local schools.

RAMMS was created to provide recreational sport options for families who may be priced out of club or travel teams.

Another factor that often deters parents from club sports involves the number of costs involved. Unlike recreational sport programs that charge one upfront fee, club and travel teams come with add-ons parents may not have accounted for.

“In club sports, you’re typically paying a monthly fee for the club, you’re paying per event fees, you’re paying admission fees to get into those sports, you’re paying for the cost of uniforms separately oftentimes,” Girard said. :There’s a lot of different add-on pieces that add up.”

Even with the higher costs, parents often feel pressure to turn to club programs for many reasons, most notably when their child specializes in one sport.

Project Play found that the most common justifications for parents to enroll their children in club sports and specialize in one sport are that their child wants to play in high school, college or professionally.

The study also found that one in four parents felt societal pressure to have their child stick to one sport while parents of older children feel the most pressure from their child and school coaches to specialize.

Girard, who’s been involved in youth sports for over eight years, said he’s noticed more younger children being pushed into club sports out of fear of being left behind.

But the great fear these days may be one of being left out by costs.

“What worries me the most about where youth sports are headed is kids leaving,” Girard said. “If it’s too expensive to play and families can’t sign up then kids stop participating.”

Rec Sports

Trump Announces ‘Patriot Games’ Showdown Involving 1 Man and Woman from Every State

NEED TO KNOW

- President Donald Trump announced plans for what a youth athletic competition he’s calling “Patriot Games”

- Trump said the games would take place in the U.S. capital and be part of a year-long celebration marking America’s 250th birthday

- The fall competition will feature one young man and one young woman from every state and territory in the country, he said

President Donald Trump announced plans for an athletic competition to help celebrate the nation’s 250th anniversary next year.

Trump, 79, announced his idea for the “Patriot Games” as part of “the most spectacular birthday party the world has ever seen” in a video shared by Freedom 250 on Thursday, Dec. 18.

“Already, we’ve had big celebrations to commemorate the 250th birthdays of the Army, the Navy and the United States Marines, but there is much, much more to come,” he said. “We’re going to have a good time.”

Trump said the Patriot Games would take place in the fall, describing the competition as “an unprecedented four-day athletic event featuring the greatest high school athletes, one young man and one young woman from each state and territory.”

He added, “But I promise there will be no men playing in women’s sports,” in a reference to his administration’s efforts to keep trans athletes from competing in sports corresponding to their gender. The president signed an executive order in February titled “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports” attempting to ban trans women from competing on women’s sports teams.

He added on Thursday, “You’re not gonna see that. You’ll see everything but that.”

The official Freedom 250 website did not share much additional information about the Patriot Games beyond what Trump said in the video. The site shared, “From opening heats to the live final day in front of a live audience, these competitors will light the torch for a new generation of Americans.”

The Patriot Games were not the only event Trump previewed on Thursday. He also announced plans for a state fair on the National Mall and “the largest fireworks display in the world,” as well as a “National Garden of American Heroes” that will feature “statues of all-time greatest Americans,” plus a “triumphal arc.”

Trump has previously teased his plans to host a UFC event at the White House as part of the country’s birthday celebrations, and gave a bit more detail about the fight on Thursday.

“It’ll be the greatest champion fighters in the world, all fighting that same night. The great Dana White is hosting, and it’s going to be something special,” he said.

ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS / AFP via Getty

Trump spoke about his plans for the nation’s milestone birthday while addressing a crowd at the Iowa State Fairgrounds on July 3. During his remarks, he announced that nationwide celebrations would take place “every one of our national parks, battlefields and historic sites.”

The celebration, he said, would include “special events,” including the UFC fight. Trump has a friendly relationship with UFC owner and CEO Dana White, who supported him at the 2024 Republican National Convention.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

“We’re going to build a little [octagon]. We’re not, Dana is going to do it. Dana is great, one of a kind,” Trump said at the time. “[There’s] going to be a UFC fight, championship fight, full fight, like 20,000 to 25,000 people, and we’re going to do that as part of ‘250’ also.”

Trump shared earlier this month that the event would take place on June 14, 2026, and would feature between eight and nine championship fights, according to USA Today.

Rec Sports

Youth Leads the Way for Men’s Basketball Against Delaware State

PHILADELPHIA – Austin Williford and Khaafiq Myers had breakout games, leading a shorthanded Saint Joseph’s men’s basketball team to a 67-51 win against the Delaware State Hornets on Thursday night.

BY THE NUMBERS

- Williford set career-highs with 14 points, four three-pointers and five steals.

- Myers tallied 11 with three assists and three rebounds.

- Overall, freshmen or redshirt freshmen combined for 30 points, 12 rebounds and five assists.

- Dasear Haskins came close to his first career double-double with nine points and eight rebounds.

- Anthony Finkley scored eight and matched Haskins for team-high honors with eight boards.

- Justice Ajogbor had four blocks. As a team, SJU blocked nine shots, the second-highest total this season for St. Joe’s.

HOW IT HAPPENED

- The Hawks started off on fire, connecting from beyond the arc on each of their first three possessions, two of them coming from Williford as SJU opened a 9-4 lead in just 86 seconds.

- Delaware State found its rhythm after a 2-for-11 start from the floor, pulling to 15-12 heading into the second media timeout. St. Joe’s responded by scoring five in a row, opening a 20-12 lead midway through the frame.

- Williford continued his impressive first half on both ends of the floor, scoring 14 points with three steals as Saint Joseph’s took a 33-18 lead into the locker room.

- In the second half, Myers picked up his offensive game, scoring nine of his points in the frame.

- SJU pushed the lead out to as many as 26 points before the Hornets made a late run to create the final score.

UP NEXT

Saint Joseph’s continues its three-game homestand, hosting Coastal Carolina on Monday, December 22. Tipoff from Hagan Arena is scheduled for 7:00 p.m. with the game to air on ESPN+.

Rec Sports

Trump announces ‘Patriot Games,’ a youth athletic competition celebrating United States’ 250th birthday | National Politics

(CNN) — President Donald Trump announced Thursday the White House will host the “Patriot Games,” a competition with young athletes from across the county, as part of the celebration of the United States’ 250th anniversary next year.

“In the fall, we will host the first ever Patriot Games, an unprecedented four-day athletic event featuring the greatest high school athletes — one young man and one young woman from each state and territory,” Trump said.

Democrats have mocked the athletic competition online, comparing it to “The Hunger Games,” a dystopian young adult novel and popular movie franchise in which children are forced to fight to the death in televised arenas.

The president revealed the plans for the Patriot Games in a video announcement from Freedom 250, which was launched Thursday. It is a “a national, non-partisan organization leading the Administration’s celebration of America’s 250th birthday,” according to a news release.

Trump previously previewed the competition in July, saying at the time it would be televised and led by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy.

During the video, Trump also highlighted his plans to begin construction soon on a new arch monument in the nation’s capital.

“We are the only major place without a triumphal arc. A beautiful triumphal arc, one like in Paris, where they have the great, a beautiful arc. They call it the Arc de Triomphe, and we’re going to have one in Washington, DC, very soon,” Trump said.

A UFC fight on the South Lawn is another of Trump’s ideas for the 250th celebration and will take place on his birthday, June 14.

“On Flag Day, we will have a one-of-a-kind UFC event here at the White House. It’ll be the greatest champion fighters in the world, all fighting that same night. The great Dana White is hosting, and it’s going to be something special,” Trump said.

Trump has long touted his desire to shape the nation’s 250th celebrations. In the past year, the Trump administration has moved quickly to align federal funding with the president’s anniversary priorities, and agencies have followed suit.

The Department of Agriculture, for instance, has embraced the president’s Great American State Fair initiative. The idea was first floated by Trump on the campaign trail in 2023, and it asks states to compete to have their fair chosen by Trump as the “most patriotic.”

Meanwhile, the White House is conducting a sweeping review of the Smithsonian Institution and has demanded the 250th content at the nation’s largest museum complex renews national pride.

This story has been updated with additional details.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2025 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

CNN’s Piper Hudspeth Blackburn contributed to this report.

-

Motorsports1 week ago

Motorsports1 week agoSoundGear Named Entitlement Sponsor of Spears CARS Tour Southwest Opener

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoBowl Projections: ESPN predicts 12-team College Football Playoff bracket, full bowl slate after Week 14

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoRobert “Bobby” Lewis Hardin, 56

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Wisconsin volleyball sweeps Minnesota with ease in ranked rivalry win

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoDonny Schatz finds new home for 2026, inks full-time deal with CJB Motorsports – InForum

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoHow Donald Trump became FIFA’s ‘soccer president’ long before World Cup draw

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoMichael Jordan’s fight against NASCAR heads to court, could shake up motorsports

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoBlack Bear Revises Recording Policies After Rulebook Language Surfaces via Lever

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoMen’s and Women’s Track and Field Release 2026 Indoor Schedule with Opener Slated for December 6 at Home

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoDavid Blitzer, Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment