Rec Sports

How Can We Optimize a Safe Return to Sport for Youth Athletes? Emergi

Introduction

Regular physical activity is one of the main contributors to optimize general health.1,2 Although regular physical activity provides many health benefits,3 such as fitness development at early ages,4 negative events sometimes happen. One of the most common negative consequences is injury. Injury is prevalent among young athletes. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention injury surveillance study,5 it was estimated 2 million injuries, 500,000 doctor visits, and 30,000 hospitalizations occur annually, which could be burdensome in both physical and psychological standpoints.6–8 Additionally, injury often leads to time loss from practices and competitions for young athletes as well as time away from their teammates.9,10 Furthermore, there is a financial burden associated with injury, which further impact organized team performance.11 Among these musculoskeletal injuries, some of the more serious musculoskeletal injuries require orthopaedic interventions, such as surgery.

One common sport injury requiring surgical intervention among young athletes is an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. The ACL tear is often observed in sports that involve cutting, pivoting, and jump-landing maneuvers such as basketball, handball, and soccer,12 and existing evidence suggests that the incidence of ACL tears is higher among young, healthy female athletes compared with their male counterparts who participate in similar sports.13 According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) data, female soccer and basketball players have 2.4 times and 4.1 times higher risk for an ACL injury than their male counterparts in the same sports at college level, respectively.14 The majority of athletes who sustain and ACL injury and hope to return to pivoting and cutting sports, go on to have an ACL reconstruction (ACLR).15 Following the ACLR surgery, post-ACLR rehabilitation is necessary to improve joint range of motion (ROM), muscular strength, and functional neuromuscular controls.16 After rehabilitation, sports medicine providers may use a battery of return-to-sports (RTS) tests to assess recovery of the surgical limb.17–19 These measures are often referenced to the contralateral limb and quantified by limb symmetry index (LSI).20–22 Recently, the importance of measures beyond physical function, specifically psychological readiness to RTS, is often assessed using tools such as ACL-Return-to-Sport-after-Injury (ACL-RSI).23,24

Many studies have reported recommendations for RTS and ACL-RSI testing following ACLR surgery.25,26 Among them, several systematic review and meta-analysis articles suggested that the outcome of the RTS tests are not associated with the future risk of ACL injury.27–29 This has been controversial since a safe RTS is a priority for all medical care professions including orthopedic physicians (orthopedic medical doctors), allied healthcare providers (physical/physiotherapists, athletic trainers), and psychological/psychiatric therapists because they are a part of this recovery process as healthcare practitioners. For athletes who complete rehabilitation and RTS tests following ACLR, re-integration into fields/court activity, with their teammates is a significant step forward and needs to be performed safely. In short, some studies27–29 report that there were no or inconsistent associations between current RTS test batteries and risk of secondary ACL injury (re-tear of graft and/or a new tear/injury to the healthy, contralateral knee). From the time of the ACL injury to the decision of RTS and return to competition, many healthcare professionals are involved. However, the literature that synthesized all of their clinical expertise and discuss the safe RTS is lacking. Therefore, the purpose of the current article was to discuss how to optimize a safe RTS from the perspective of multidisciplinary sports medicine healthcare practitioners and synthesize them with research-based evidence using a clinical scenario involving a female athlete following ACL injury.

Clinical Scenario

Who

A 19-year-old, competitive female college basketball player (position: small forward)

What Happened

During a basketball game, the patient jumped for a rebound and hyperextended her left knee on landing. She immediately felt significant pain and could not continue playing.

Diagnosis

ACL rupture, confirmed by MRI.

Special Note

The patient had a previous history of an ACL tear on the contralateral (right knee) 4 years prior when she was 15 years old. At that time, the hamstring tendon was harvested from the affected limb and used as a graft for her ACLR. Despite this being her 2nd ACL tear, her goal is to return to basketball activities.

ACLR Surgery

The patient had surgery 4 weeks following the ACL injury. At this time, ACLR with bone-patellar tendon-bone (BTB) graft procedure was performed.

Progress Following ACLR

Post-operative rehabilitation began immediately following her ACLR. Her initial post-operative course began without complications, with adequate pain control, and no concern for infection. Once the inflammation and pain had subsided, she started active and passive ROM exercises and isometric muscle contraction under the guidance of her physical therapist. Once she made further progress, she started performing isotonic exercises with near full ROM using a tubing band and weight at the ankle. She was able to jog at 3 months without noticeable pain or compensatory mechanics. From 3 months to 6 months, her rehabilitation exercises involved (basic) agility, balance, and plyometrics in conjunction with fundamental basketball movements. After 6 months, her rehabilitation incorporated more functional training including various sport-specific (basketball-based) drills.

RTS Test

At 9 months post-operatively, she performed a series of RTS tests with the following results:

a) Thigh circumference – 10 cm from top of the patellar

i. Right limb: 43.5 cm

ii. Left limb: 42.0 cm

b) Knee extension ROM

i. Right limb: −4 degrees

ii. Left limb: 0 degree

c) Knee flexion ROM

i. Right limb: 145 degrees

ii. Left limb: 142 degrees

d) Isokinetic test – Concentric contractions at 60 degrees/sec

i. Quadriceps: LSI 82%

ii. Hamstrings: LSI 86%

iii. Hamstrings/Quadriceps (H/Q) ratio: 58%

e) Hop tests for distance and time

i. Single-Leg Hop: LSI 80%

ii. Single-Leg Triple Hop: LSI 76%

iii. Single-Leg Crossover Hop: LSI 72%

iv. Single-Leg Timed Hop: LSI 84%

In addition to the three RTS tests, ACL-RSI was collected:

f) ACL-RSI (out of 100)

i. Overall scores: 51.2

ii. Confidence in performance subscale: 58.8

iii. Emotional subscale: 40.1

iv. Risk appraisal subscale: 55.4

RTS Recommendations/Perspectives

From an Orthopaedic Surgeon

This patient, unfortunately, underwent a second ACLR surgery: one for each knee, not revision ACLR. Evidence suggested that patient-reported outcome measures including Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and Lysholm scores of the revision ACL injury patients are much worse than primary ACL injury patients.30 Moreover, weaker muscle strength, lower Tegner activity levels, and more severe osteoarthritis signs were found in the revision ACL injury patients compared to the primary ACL injury patients.30 It was, indeed, unfortunate; however, could be considered as fortunate that the second ACL injury occurred in contralateral limb, not a revision (not a re-tear of the graft on the same, ipsilateral knee). From this reason, I am cautiously optimistic for her to gain good knee joint stability and neuromuscular function through a post-operative rehabilitation. Yet, I have a concern. Anecdotally, young athletes who sustained ACL injury two times, regardless revisions or contralateral tear, tend to move each of the rehabilitative milestones quicker than primary ACL injury patients. This may be because they have gone through rehabilitative exercises of each phase previously. The familiarity of the rehabilitative process may facilitate the swift pace. However, instead of aiming a speedy recovery, I highly suggest to take adequate time to perform rehabilitative exercises with good quality of movement. Another concern I have is a use of the LSI measures. Since she had an ACL tear on her right knee 4 years prior, it is difficult and some ways invalid to assess the stability, strength, and function of her left knee using LSI measures.

Overall, since she has already sustained two ACL injuries, it would be beneficial to examine morphologic factors (example, posterior tibial slop), familial history, concomitant meniscus or cartilage injury, and knee and general joint laxity. Then, depending on the identified factors and in scenario of another ACLR, additional surgical procedure such as anterolateral complex augmentation during ACLR including lateral extraarticular tenodesis (LET) or anterolateral ligament reconstruction (ALLR), or slope reduction osteotomy should be considered. Orthopaedic surgeons need to be fully aware of the risk of further ACL injury and conduct pre-operative planning for high-risk patients who wish to return to sporting activities.

From an Academic-Physiotherapist

Considering that she had also ACLR on her right knee 4 years ago (deficits in her right lower extremity may have persisted), the interlimb comparisons (left/right) should not be taken as the only performance index. Reference values for the isokinetic strength and jump test reference values are available for elite female basketball players after ACLR:31 as an example, peak torque/body weight values allow for better interpretation of the strength potential (when compared to LSI). Pre-injury screening data (eg pre-season team testing), when available, are also a valuable reference source.32 Following recent neuroscience research advances, it is crucial to include neurocognitive loads (and motor dual-task challenges) both in rehabilitation and testing (eg visual-cognitive hop tests), as performance deficits are not only related to the physical status of the athlete.33

As the young age and the two ACLRs put her at higher risk for further injury, her training in return to competition should/must be optimized, with the goal to possibly reach her pre-injury performance.34,35 Psychological readiness is associated with RTS and return to pre-injury level of performance.35,36 The ACL-RSI scores should be interpreted with caution, considering that the “optimal psychological profile” differs between individuals.36 Ideally, this scale should be further implemented during the RTS process, to monitor the changes in the psychological profile over time. Her overall score at 9 months post-ACLR (51.2 points) indicates that her psychological readiness for a potential RTS is not yet sufficient, and that she needs more time and work to regain her confidence mentally and emotionally.37 The strengthening and conditioning program should be intensified, as well as the basketball-specific training. Waters et al38 described a set of basketball-specific movement drills (skill drills, reactive drills, contact drills, and combinations of each of these). The training progression needs to be performed at many levels: from low-intensity to high-intensity drills, from 1:1 drills with the sport PT/ATC to group practice, from no-contact to contact drills (defensive/offensive).39 As the ideal test battery does not exist, the training drills are also used as test situations, where the staff (PT/ATC, coaches) evaluate the player’s ability to master technically, physically and mentally these basketball-specific and complex demands.40 The ultimate goal is to re-integrate the (optimally prepared) player in full-contact, unrestricted team practice, following shared-decision making among all stakeholders (athlete, medical team, coaching staff). She should also implement neuromuscular exercises (eg core/hip stabilization, reactive stabilization drills for the lower extremity, …) in her warm-up routine, in terms of secondary prevention.41 Eventually, and if the athlete asks for, she could benefit from the professional help of a sport psychologist/mental health practitioner during the RTS/return to performance process.42

From a Sports Psychiatrist

The total ACL-RSI and each of the subscales are scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing greater psychological readiness to return to sport.43 Various thresholds have been implemented, but multiple studies have suggested that total scores less than 56 to 62 points are associated with increased difficulty returning to one’s previous level of sport participation.37,44,45 One study found that the risk appraisal subscale took the longest to improve after ACLR and had a significant impact on the ability for athletes to return to sports.46 This patient scored relatively low on the overall score as well as the subscales, suggesting that early implementation of psychological interventions would likely be helpful. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in particular could be beneficial to target maladaptive thought patterns or emotional factors, both of which could significantly impact the likelihood of successful RTS.

It is important to recognize that sport-related injuries can be traumatic for young athletes and may be associated with psychological responses similar to those seen with post-traumatic stress. Given the prolonged nature of recovery after ACLR and the rigorous rehabilitation required to return to sports, sustaining an ACL tear can be devastating for an athlete. This is particularly true for athletes sustaining a second ACL tear (whether contralateral ACL or ipsilateral/graft tear), after having already overcome the myriad physical and psychological challenges associated with this type of injury. While many athletes undergoing ACLR might benefit from formal psychological treatment such as CBT, all sports medicine and allied health providers can participate in supporting the mental health of these athletes by simply asking how they are doing emotionally throughout the entire course of recovery, validating their experiences, encouraging help-seeking behaviors, and providing support when needed.

From a Clinical Physical Therapist

Given that this injury is this patient’s second lifetime ACL injury, we must take caution in her RTS progression. As discussed previously, the familiarity this patient has with the rehabilitation process could promote a swifter progression through her rehabilitation. Therefore, it is the duty of her rehabilitation team to ensure she is reaching the milestones set at each stage and moving along with appropriate pace. In looking at the RTS process as a continuum as originally proposed by Ardern and other physical therapy experts as a consensus statement47 and later discussed by Meredith et al48 . The process of “return to sport” can be broken down into three parts: “return to participation”, “return to sport”, and “return to performance”, and step-by-step return to approach is clinically feasible (Figure 1). While she currently does not achieve a 10% threshold in LSI scores of both strength and hop tests, the “return to participation” phase is ideal step for her at this time. “Return to participation” is defined as a return to training below the level at which she had been participating in sport prior to her injury. This type of training can include activities that she would not be participating in with her teammates such as non-contact cutting and pivoting drills. She could start in a highly controlled environment and gradually progress to a more challenging environment, simulating more team practice-oriented environments.

|

Figure 1 Step-by-Step Return Approach Model.

|

In deciding on when to progress her to the “return to sport” phase of training, she should perform the battery of hop testing and strength testing as she has been tested with these measures previously and progress can be objectively tracked with these measures. However, in agreement with other clinicians, these tests should not be the only measures to consider in her RTS testing as she has had previous ACLR surgery on her contralateral limb, affecting the comparison of each limb. Quality of her movement patterns during plyometric and cutting/pivoting drills should be considered as well. Once the patient has achieved strength and hop testing within 10% and she has demonstrated improvement in her movement patterns, she can progress to the “return to sport” phase in which she would gradually integrate into her team practices, but not at the desired level of performance. This phase begins progressing from non-contact drills, to contact drills, then game-like scrimmages and finally a return to competitive play. During this progression, the rehabilitation team would be checking in with the athlete to monitor for signs of diminished strength, ROM, or pain as indicators as to whether or not she can continue the progression. Finally, she would enter the “return to performance” phase. In this phase, she would continue to progress her strength, agility, and sport-specific functional skillsets, ideally with a strength and conditioning specialist/fitness coach, to progress towards pre-injury levels of play. This can be the longest phase of the RTS process as it can last one to two years past her ACLR surgical date.

A continuum-based approach to the RTS process can be highly beneficial for the athlete for a variety of reasons. It encourages the athlete and rehabilitation team to have ongoing evaluations upwards of two years past the surgical date to assess for any deficits of strength, pain, ROM and psychological readiness for sport. This athlete, in particular, does demonstrate through her psychological readiness testing that she does have apprehension for RTS; therefore, a stepwise progression of RTS approach may be feasible to improve her confidence in her sport as she advances through her phases of RTS. Further, this stepwise approach likely facilitates professional communications among the athlete/patient, rehabilitation therapists, and coaching staff members. One important aspect of this stepwise approach is to establish clear goals in each phase. Finally, in looking at the RTS as a continuum, the athlete could progress or regress depending on her responses to each goal that she achieves in her journey back to sport.

From a Performance and Sport Scientist

This young female basketball player still demonstrated inadequate LSI values in peak muscle torque of quadriceps (82%) and hamstring (86%) as well as single leg hop tests (ranges from 72% to 84%), and it is concerning. Several articles suggested ≥90% of the LSI for safe RTS.26,49 One of the studies reported 84% of quadriceps LSI values in no ACL re-injury group compared to 75% in re-injured group at the time of RTS following ACLR.50 One good news is her H/Q ratio. Her H/Q ratio was 58%, which may be clinically sufficient. One documented evidence showed H/Q ratio of 58% in concentric muscle contraction at angular speed 60°/s did not have ACL graft rupture while those who sustained a graft rupture showed H/Q ratio of 53% after ACLR.51 The hamstring muscles are considered to take a protective role as an agonist to ACL by resisting the anterior tibial displacement that results from quadriceps muscle forces at the knee.51 Thus, although she showed an acceptable H/Q ratio at this point, I encourage her to keep strengthening hamstring muscles.

To facilitate a safe RTS for her, we need to understand unique features of basketball. Female basketball players typically cover a total of 5214 ± 315 meters with 576 ± 110 movement changes in a match.52 Also, basketball players alter their movement patterns every 1–3 seconds during a match while spending approximately 34% of their time in running and jumping activities.53,54 Understanding those basketball-specific movement characteristics is beneficial to develop a sport-specific rehabilitation program and likely helps facilitate a safe RTS progression. Moreover, optimizing the load progression with respect to her basketball level (eg college, recreational, or professional), specific position (eg center, forward, or guard), and ideal timing (eg during a regular season, off-season, or perhaps, pre-season) need to be considered. During the on-court phase of the RTS, it is crucial to optimize her physical load (eg base on principle of progressive overload) with aim of avoiding rapid spikes in her training.55 Also, not only her physical load control, her mental fitness/health in relation to on-court phase of the RTS process need to be monitored. Recent studies showed lower psychological readiness in RTS in females compared to males.56,57 In short, in the on-court phase of the RTS process, a clinical practitioner such as athletic trainer, fitness coach, and strength and conditioning specialist needs to implement a sport-specific rehabilitation, control workload, and pay attention to psychological/mental status.

One of the recent RTS frameworks respecting specific sport content is called a control-chaos continuum (CCC), which was originally designed for on-pitch rehabilitation in elite soccer58 and later adapted also on basketball.39 Briefly, the CCC principle described importance of gym-based physical preparation and on-court rehabilitation, which are progressing from high control training stimuli, through moderate control, control to chaos, moderate chaos and finally high chaos stimuli/conditions.39 During the last stage (the high chaos stimuli/conditions phase), athlete should be able to reach >90% maximal running speed, positional specific acceleration, repeated change of directions with adequate speed and without pain, and specific jump-landing actions (eg shooting, rebounding, and blocking). Those sport-specific drills need to be carefully performed and progressed with qualified clinical practitioners in relation to the athlete’s overall physical (eg pain) and mental (eg fear) states.

Discussion

The purpose of the current commentary was to discuss how to optimize a safe RTS following ACLR based on clinical perspectives from various sports medicine healthcare practitioners and also to synthesize their recommendations with research evidence. In this case, the young female basketball player had two ACLR surgeries, one in each limb. As the orthopaedic surgeon and academic-physiotherapist were concerned, it would not be reliable to use the LSI as a mean of the RTS because the reference knee for the LSI (her right knee) had a previous ACLR surgery 4 years prior. Even though the initial surgery was 4 years ago, it may alter the LSI values, possibly inflating the LSI values of her left knee since the right knee may not be 100%. So, what would be a good way to evaluate a safe RTS in this scenario? As suggested by the performance and sport scientist, H/Q ratio may be an option. It was evidenced that higher H/Q ratio (higher hamstring strength in relation to quadriceps strength) is protective to initial ACL tear59 and graft re-tear.51 This approach does not require another limb as a reference, however it may be deceiving in a case where quadriceps strength is significantly impacted resulting in a higher ratio, rather than higher hamstring strength driving the improvement in this metric. Alternatively, according to the academic-physiotherapist, peak torque/body weight values were reported in the past study31 and may be an option. In this study, isokinetic strength (60 deg/sec, 180 deg/sec, and 300 deg/sec) of the quadriceps and hamstrings were presented in elite and nonelite of female basketball players.31 If an isokinetic machine is available, one study reported age-, sex-, and graft used in ACLR-specific quadriceps and hamstrings strength values,60 and using the reported data as a reference may be another useful approach. Additionally, the academic-physiotherapist suggested including neurocognitive load evaluation in RTS. Incorporating neurocognitive load in rehabilitation is a fairly new idea. Several recent studies suggested assessing neurocognitive and neurophysiological functions for those who have a torn ACL.61–64 One of the articles discussed importance of re-acquisition of motor skills and training of neuroplastic capacities during rehabilitation, which may potentially help reducing subsequent ACL injury.61,62 In short, the concept of the neurocognitive load into rehabilitation and possibly RTS tests is emerging, and more evidence is necessary; however, this may be beneficial for the current scenario, if the theory is that neurocognitive deficits in this athlete may have contributed to the increased risk of ACL injury.

Another major concern voiced by multiple experts was low ACL-RSI scores presented at 9 months following ACLR surgery. The low ACL-RSI scores may be due to this being her second time sustaining an ACL tear. A sports psychiatrist pointed out that the ACL-RSI score ranges of 56–62 are associated with difficult to reach previous level of athletic participation. One study found that the ACL-RSI score was lower at 12 months following ACLR for those who resulted in second ACL injury among 20 years or younger.65 The reported mean ACL-RSI scores of those who sustained the second ACL injury at 12 months in this study was 60.8.65 The sports psychiatrist suggested the use of CBT to help psychological state of this young female basketball player. CBT has been commonly prescribed to treat anxiety and depression,66–68 but there has been only one study related to CBT intervention to ACL patients.69 In this study, young athletes who had ACLR surgery had a telephone-based cognitive-behavioral based physical therapy intervention for 8 weeks.69 At 6 months, all patients who completed this intervention demonstrated meaningful change measured by minimal clinically important difference (MCID) on International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), sport/recreation and quality of life subscales of Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK).69 Since only one study was documented, and the title of this study was a pilot study,69 more evidence is necessary, especially how the CBT-based intervention affects ACL-RSI scores and subsequent ACL injury risk. Additionally, a few studies found that female athletes tend to demonstrate lower ACL-RSI scores compared to their male counterparts.56,57 Therefore, psychological intervention may need to be targeted to female athletes more than male athletes.

The clinical physical therapist presented a step-by-step RTS approach, which consists of “return to participation”, “return to sport”, and “return to performance”.48 In this article, the “return to participation” consisted of two specific components: progression to unrestricted training and clearance to full participation.48 In this case, the young female basketball player did not reach to previously advocated, commonly used less than 10% of deficits in many RTS tests,26 she is still in this phase (progression to unrestricted training). A similar concept was presented in other articles, which broke down the safe RTS to the following 4 phases: 1) on-field rehabilitation, 2) return to training, 3) return to competitive match play, and 4) return to play.70,71 One of the articles emphasized to focus on restoring movement quality, physical conditioning, and sport-specific skills during the on-field rehabilitation phase.71 Furthermore, this article highlighted importance of progressive loading during this phase. Synthesizing these suggestions into progression to unrestricted training in “return to participation” phase based on this case, this young female athlete should practice various drills in a controlled environment with emphasis of movement quality, physical conditioning and sport-specific skills under appropriate, progressive loads. Sport-specific drills (in this scenario basketball) can be found in an article titled “Suggestions from the field for RTS participation following ACLR: Basketball”.39 During this phase, managing pain, swelling, and any other clinical symptoms that may be a reflection of the last phase of this rehabilitation are necessary,72 and clinician(s) need to have a good communication with the athlete. After this the initial stage (return to participation), “return to sport” and “return to performance” are the next two steps.48 In these phases, reconditioning could be another challenging aspect. The reconditioning could be defined as “re-establishing and/or improving an athlete’s overall physical fitness after an injury or surgery”.73 One study identified diminished aerobic capacity quantified by VO2max followed by ACLR in relation to a matched healthy control.74 In addition to the aerobic fitness, the final stage of the RTS needs to simulate a real game/competition-like situation. Visual-spatial, decision-making, and perturbation training are recommended.73 Using perturbation training as an example, the perturbation needs to be simulated by specific position(s) of the athlete and specific movement(s) the athlete commonly performs in conjunction with how opponent(s) tends to move, and potentially with physical perturbance/pressure. Lastly, commented by the performance and sport scientist, the rehabilitation and the RTS process should be performed in relation to the context of the sport each athlete is hoping to return including level, position, and timing. Recent studies highlighted importance of controlling workload55 and challenges associated with the work load (eg levels of chaos in the RTS continuum).39,58 A medical team member such as athletic trainer, fitness coach, and strength and conditioning specialist, if available, should play a major role for bridging the post-RTS to the “return-to-performance”.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this article. Firstly, this article was not written based on actual study or experiment performed. Therefore, the concepts written in this article need a validation. Secondly, this article was a synthesis of experts’ opinions and existing literature, not a systematic review; thus, evidence level is low. Lastly, experts’ input was presented in one clinical scenario. Each ACL injury and re-tear clinical case and scenario is unique; therefore, the generatability of this article is limited to young athletes who are willing to return to competitive sports.

Conclusion

In this article, several important ideas were discussed by various sports medicine healthcare practitioners and synthesized with recent research findings to facilitate the safe RTS following ALCR using a scenario. Collectively, the professional recommended incorporating neurocognitive load into rehabilitation, psychological interventions such as CBT, and a step-by-step RTS approach as emerging concepts for young athletes. Even after the RTS test, on-site clinicians need to control the appropriate workload of each athlete in this chaotic returning continuum. More empirical research studies are necessary to substantiate the voices from the experts in this article, which may help reduce unfortunate another tear following primary ACLR surgery among young athletes.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

All authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. All authors have no financial issues related to the current manuscript. The clinical scenario used in the current article is a fictional case.

References

1. Blair SN, Kohl HW, Gordon NF, Paffenbarger RS Jr. How much physical activity is good for health? Ann Rev Public Health. 1992;13:99–126. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.13.050192.000531

2. Bauman A, Owen N. Physical activity of adult Australians: epidemiological evidence and potential strategies for health gain. J Sci Med Sport. 1999;2(1):30–41. doi:10.1016/S1440-2440(99)80182-0

3. Malm C, Jakobsson J, Isaksson A. Physical activity and sports-real health benefits: a review with insight into the public health of Sweden. Sports. 2019;7(5):127. doi:10.3390/sports7050127

4. Lloyd RS, Oliver JL, Faigenbaum AD, et al. Long-term athletic development- part 1: a pathway for all youth. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2015;29(5):1439–1450. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000756

5. Comstock RD, Knox C, Yard E, Gilchrist J. Sports-related injuries among high school athletes–United States, 2005-06 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(38):1037–1040.

6. Malekpour M-R, Rezaei N, Azadnajafabad S. Global, regional, and national burden of injuries, and burden attributable to injuries risk factors, 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Public Health. 2024;237:212–231. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2024.06.011

7. Nippert AH, Smith AM. Psychologic stress related to injury and impact on sport performance. Phys Med Rehab Clin North Am. 2008;19(2):399–418, x. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2007.12.003

8. Haraldsdottir K, Watson AM. Psychosocial impacts of sports-related injuries in adolescent athletes. Current Sports Med Rep. 2021;20(2):104–108. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000809

9. Mosler AB, Carey DL, Thorborg K, et al. In professional male soccer players, time-loss groin injury is more associated with the team played for than with training/match-play duration. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2022;52(4):217–223. doi:10.2519/jospt.2022.10845

10. Mendes-Cunha S, Moita JP, Xarez L, Torres J. Dance-related musculoskeletal injury leading to forced time-loss in elite pre professional dancers – a retrospective study. Physic Sports Med. 2023;51(5):449–457. doi:10.1080/00913847.2022.2129503

11. Eliakim E, Morgulev E, Lidor R, Meckel Y. Estimation of injury costs: financial damage of English Premier League teams’ underachievement due to injuries. BMJ Open Sport Exercise Med. 2020;6(1):e000675. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000675

12. Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Paterno MV, Quatman CE. Mechanisms, prediction, and prevention of ACL injuries: cut risk with three sharpened and validated tools. J Orthopaedic Res. 2016;34(11):1843–1855. doi:10.1002/jor.23414

13. Mancino F, Kayani B, Gabr A, Fontalis A, Plastow R, Haddad FS. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: risk factors and strategies for prevention. Bone Joint Open. 2024;5(2):94–100. doi:10.1302/2633-1462.52.BJO-2023-0166

14. Arendt EA, Agel J, Dick R. Anterior cruciate ligament injury patterns among collegiate men and women. J Athletic Train. 1999;34(2):86–92.

15. Jin H, Tahir N, Jiang S, et al. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Sports Med Open. 2025;11(1):40. doi:10.1186/s40798-025-00844-7

16. Cavanaugh JT, Powers M. ACL rehabilitation progression: where are we now? Current Rev Musculoskel Med. 2017;10(3):289–296. doi:10.1007/s12178-017-9426-3

17. Golberg E, Sommerfeldt M, Pinkoski A, Dennett L, Beaupre L. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction return-to-sport decision-making: a scoping review. Sports Health. 2024;16(1):115–123. doi:10.1177/19417381221147524

18. Sugimoto D, Heyworth BE, Carpenito SC, Davis FW, Kocher MS, Micheli LJ. Low proportion of skeletally immature patients met return-to-sports criteria at 7 months following ACL reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2020;44:143–150. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.05.007

19. Sugimoto D, Milewski MD, Williams KA, et al. Effect of age and sex on anterior cruciate ligament functional tests approximately 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy Sports Med Rehab. 2024;6(3):100897. doi:10.1016/j.asmr.2024.100897

20. Gokeler A, Dingenen B, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation and return to sport testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: where are we in 2022? Arthroscopy Sports Med Rehab. 2022;4(1):e77–e82. doi:10.1016/j.asmr.2021.10.025

21. Maguire K, Sugimoto D, Micheli LJ, Kocher MS, Heyworth BE. Recovery after ACL reconstruction in male versus female adolescents: a matched, sex-based cohort analysis of 543 patients. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2021;9(11):23259671211054804. doi:10.1177/23259671211054804

22. Sugimoto D, Heyworth BE, Brodeur JJ, Kramer DE, Kocher MS, Micheli LJ. Effect of graft type on balance and hop tests in adolescent males following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Sport Rehab. 2019;28(5):468–475. doi:10.1123/jsr.2017-0244

23. Webster KE, Feller JA. Evaluation of the responsiveness of the anterior cruciate ligament return to sport after injury (ACL-RSI) scale. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2021;9(8):23259671211031240. doi:10.1177/23259671211031240

24. Webster KE, Feller JA. Psychological readiness to return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the adolescent athlete. J Athletic Train. 2022;57(9–10):955–960. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-0543.21

25. Lorange JP, Senécal L, Moisan P, Nault ML. Return to sport after pediatric anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of the criteria. Am J Sports Med. 2024;52(6):1641–1651. doi:10.1177/03635465231187039

26. Adams D, Logerstedt DS, Hunter-Giordano A, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(7):601–614. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.3871

27. Zhou W, Liu X, Hong Q, Wang J, Luo X. Association between passing return-to-sport testing and re-injury risk in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2024;12:e17279. doi:10.7717/peerj.17279

28. Losciale JM, Zdeb RM, Ledbetter L, Reiman MP, Sell TC. The association between passing return-to-sport criteria and second anterior cruciate ligament injury risk: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(2):43–54. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8190

29. Gill VS, Tummala SV, Sullivan G, et al. Functional return-to-sport testing demonstrates inconsistency in predicting short-term outcomes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2024;40(7):2135–2151.e2132. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2023.12.032

30. Gifstad T, Drogset JO, Viset A, Grøntvedt T, Hortemo GS. Inferior results after revision ACL reconstructions: a comparison with primary ACL reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol arthroscopy. 2013;21(9):2011–2018. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2336-4

31. van Melick N, van der Weegen W, van der Horst N. Quadriceps and hamstrings strength reference values for athletes with and without anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction who play popular pivoting sports, including soccer, basketball, and handball: a scoping review. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2022;52(3):142–155. doi:10.2519/jospt.2022.10693

32. Bizzini M, Silvers HJ. Return to competitive football after major knee surgery: more questions than answers? J Sports Sci. 2014;32(13):1209–1216. doi:10.1080/02640414.2014.909603

33. Grooms DR, Chaput M, Simon JE, Criss CR, Myer GD, Diekfuss JA. Combining neurocognitive and functional tests to improve return-to-sport decisions following ACL reconstruction. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(8):415–419. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.11489

34. Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders A, et al. 2016 consensus statement on return to sport from the first world congress in sports physical therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(14):853–864. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096278

35. Meredith SJ, Rauer T, Chmielewski TL, et al. Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: panther symposium ACL injury return to sport consensus group. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2020;8(6):2325967120930829. doi:10.1177/2325967120930829

36. Webster KE, McPherson AL, Hewett TE, Feller JA. Factors associated with a return to preinjury level of sport performance after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(11):2557–2562. doi:10.1177/0363546519865537

37. Sadeqi M, Klouche S, Bohu Y, Herman S, Lefevre N, Gerometta A. Progression of the psychological ACL-RSI score and return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective 2-year follow-up study from the french prospective anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction cohort study (FAST). Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2018;6(12):2325967118812819. doi:10.1177/2325967118812819

38. Waters E. Suggestions from the field for return to sports participation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: basketball. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):326–336. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.4030

39. Taberner M, Spencer N, Murphy B, Antflick J, Cohen DD. Progressing on-court rehabilitation after injury: the control-chaos continuum adapted to basketball. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(9):498–509. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.11981

40. Welling W. Return to sports after an ACL reconstruction in 2024 – A glass half full? A narrative review. Phys Ther Sport. 2024;67:141–148. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2024.05.001

41. Di Stasi S, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training to target deficits associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(11):777–792, a771–711. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.4693

42. Forsdyke D, Gledhill A, Ardern C. Psychological readiness to return to sport: three key elements to help the practitioner decide whether the athlete is REALLY ready? Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(7):555–556. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096770

43. Webster KE, Feller JA. Development and validation of a short version of the anterior cruciate ligament return to sport after injury (ACL-RSI) scale. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2018;6(4):2325967118763763. doi:10.1177/2325967118763763

44. Faleide AGH, Inderhaug E. It is time to target psychological readiness (or lack of readiness) in return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament tears. J Exp Orthopaedics. 2023;10(1):94. doi:10.1186/s40634-023-00657-1

45. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Whitehead TS, Webster KE. Psychological responses matter in returning to preinjury level of sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1549–1558. doi:10.1177/0363546513489284

46. Kim Y, Kubota M, Sato T, Inui T, Ohno R, Ishijima M. Psychological patient-reported outcome measure after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: evaluation of subcategory in ACL-return to sport after injury (ACL-RSI) scale. Orthopaedics Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108(3):103141. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2021.103141

47. Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders AG, et al. Infographic: 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the first world congress in sports physical therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(13):995. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097468

48. Meredith SJ, Rauer T, Chmielewski TL, et al. Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: panther symposium ACL injury return to sport consensus group. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(8):2403–2414. doi:10.1007/s00167-020-06009-1

49. Dingenen B, Gokeler A. Optimization of the return-to-sport paradigm after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a critical step back to move forward. Sports Med. 2017;47(8):1487–1500. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0674-6

50. Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(13):804–808. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031

51. Kyritsis P, Bahr R, Landreau P, Miladi R, Witvrouw E. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(15):946–951. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095908

52. Scanlan AT, Dascombe BJ, Reaburn P, Dalbo VJ. The physiological and activity demands experienced by Australian female basketball players during competition. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15(4):341–347. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2011.12.008

53. Narazaki K, Berg K, Stergiou N, Chen B. Physiological demands of competitive basketball. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(3):425–432. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00789.x

54. Ostojic SM, Mazic S, Dikic N. Profiling in basketball: physical and physiological characteristics of elite players. J Strength Conditioning Res. 2006;20(4):740–744. doi:10.1519/R-15944.1

55. Blanch P, Gabbett TJ. Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute: chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(8):471–475. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095445

56. Milewski MD, Traver JL, Coene RP, et al. Effect of age and sex on psychological readiness and patient-reported outcomes 6 months after primary ACL reconstruction. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2023;11(6):23259671231166012. doi:10.1177/23259671231166012

57. Obradovic A, Manojlovic M, Rajcic A, et al. Males have higher psychological readiness to return to sports than females after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exercise Med. 2024;10(4):e001996. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2024-001996

58. Taberner M, Allen T, Cohen DD. Progressing rehabilitation after injury: consider the ‘control-chaos continuum’. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(18):1132–1136. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100157

59. Myer GD, Ford KR, Barber Foss KD, Liu C, Nick TG, Hewett TE. The relationship of hamstrings and quadriceps strength to anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19(1):3–8. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e318190bddb

60. Kuenze C, Weaver A, Grindstaff TL, et al. Age-, sex-, and graft-specific reference values from 783 adolescent patients at 5 to 7 months after ACL reconstruction: IKDC, Pedi-IKDC, KOOS, ACL-RSI, single-leg hop, and thigh strength. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(4):194–201. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.11389

61. Gokeler A, Neuhaus D, Benjaminse A, Grooms DR, Baumeister J. Correction to: principles of motor learning to support neuroplasticity after ACL injury: implications for optimizing performance and reducing risk of second ACL injury. Sports Med. 2019;49(6):979. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01078-w

62. Gokeler A, Neuhaus D, Benjaminse A, Grooms DR, Baumeister J. Principles of motor learning to support neuroplasticity after ACL injury: implications for optimizing performance and reducing risk of second ACL injury. Sports Med. 2019;49(6):853–865. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01058-0

63. Chaput M, Criss CR, Onate JA, Simon JE, Grooms DR. Neural activity for uninvolved knee motor control after ACL reconstruction differs from healthy controls. Brain Sci. 2025;15(2):109. doi:10.3390/brainsci15020109

64. An YW, Lobacz AD, Baumeister J, et al. Negative emotion and joint-stiffness regulation strategies after anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Athletic Train. 2019;54(12):1269–1279. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-246-18

65. McPherson AL, Feller JA, Hewett TE, Webster KE. Psychological readiness to return to sport is associated with second anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(4):857–862. doi:10.1177/0363546518825258

66. Apolinário-Hagen J, Drüge M, Fritsche L. Cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance commitment therapy for anxiety disorders: integrating traditional with digital treatment approaches. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:291–329.

67. Lee SH, Cho SJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depressive disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1305:295–310.

68. Oar EL, Johnco C, Ollendick TH. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):661–674. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.002

69. Coronado RA, Sterling EK, Fenster DE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral-based physical therapy to enhance return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an open pilot study. Phys Ther Sport. 2020;42:82–90. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.01.004

70. Buckthorpe M, Frizziero A, Roi GS. Update on functional recovery process for the injured athlete: return to sport continuum redefined. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(5):265–267. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099341

71. Buckthorpe M, Della Villa F, Della Villa S, Roi GS. On-field rehabilitation part 1: 4 pillars of high-quality on-field rehabilitation are restoring movement quality, physical conditioning, restoring sport-specific skills, and progressively developing chronic training load. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):565–569. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8954

72. Buckthorpe M, Della Villa F, Della Villa S, Roi GS. On-field rehabilitation part 2: a 5-stage program for the soccer player focused on linear movements, multidirectional movements, soccer-specific skills, soccer-specific movements, and modified practice. J Orthopaedic Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):570–575. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8952

73. Gokeler A, Grassi A, Hoogeslag R, et al. Return to sports after ACL injury 5 years from now: 10 things we must do. J Exp Orthopaedics. 2022;9(1):73. doi:10.1186/s40634-022-00514-7

74. Slater LV, Hart JM. Quantifying the relationship between quadriceps strength and aerobic fitness following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2022;55:106–110. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2022.03.005

Rec Sports

Tahoe-Truckee Unified School District caught up in a dispute over transgender athlete policies

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — A Lake Tahoe school district is caught between California and Nevada’s competing policies on transgender student athletes, a dispute that’s poised to reorder where the district’s students compete.

High schools in California’s Tahoe-Truckee Unified School District, set in a mountainous, snow-prone area near the border with Nevada, have for decades competed in the Nevada Interscholastic Activities Association, or NIAA. That has allowed sports teams to avoid making frequent and potentially hazardous trips in poor winter weather to competitions farther to the west, district officials say.

But the Nevada association voted in April to require students in sex-segregated sports programs to play on teams that align with their sex assigned at birth — a departure from a previous approach allowing individual schools to set their own standards. The move raised questions for how the Tahoe-Truckee district would remain in the Nevada association while following California law, which says students can play on teams consistent with their gender identity.

Now, California’s Department of Education is requiring the district to join the California Interscholastic Federation, or CIF, by the start of next school year.

District Superintendent Kerstin Kramer said at a school board meeting this week the demand puts the district in a difficult position.

“No matter which authority we’re complying with we are leaving students behind,” she said. “So we have been stuck.”

There are currently no known transgender student athletes competing in high school sports in Tahoe-Truckee Unified, district officials told the education department in a letter. But a former student filed a complaint with the state in June after the board decided to stick with Nevada athletics, Kramer said.

A national debate

The dispute comes amid a nationwide battle over the rights of transgender youth in which states have restricted transgender girls from participating on girls sports teams, barred gender-affirming surgeries for minors and required parents to be notified if a child changes their pronouns at school. At least 24 states have laws barring transgender women and girls from participating in certain sports competitions. Some of the policies have been blocked in court.

Meanwhile, California is fighting the Trump administration in court over transgender athlete policies. President Donald Trump issued an executive order in February aimed at banning transgender women and girls from participating in female athletics. The U.S. Justice Department also sued the California Department of Education in July, alleging its policy allowing transgender girls to compete on girls sports teams violates federal law.

And Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has signed laws aimed at protecting trans youth, shocked party allies in March when he raised questions on his podcast about the fairness of trans women and girls competing against other female athletes. His office did not comment on the Tahoe-Truckee Unified case, but said Newsom “rejects the right wing’s cynical attempt to weaponize this debate as an excuse to vilify individual kids.”

The state education department said in a statement that all California districts must follow the law regardless of which state’s athletic association they join.

At the Tahoe-Truckee school board meeting this week, some parents and one student said they opposed allowing trans girls to participate on girls teams.

“I don’t see how it would be fair for female athletes to compete against a biological male because they’re stronger, they’re taller, they’re faster,” said Ava Cockrum, a Truckee High School student on the track and field team. “It’s just not fair.”

But Beth Curtis, a civil rights attorney whose children attended schools in Tahoe-Truckee Unified, said the district should fight NIAA from implementing its trans student athlete policy as violating the Nevada Constitution.

Asking for more time

The district has drafted a plan to transition to the California federation by the 2028-2029 school year after state officials ordered it to take action. It’s awaiting the education department’s response.

Curtis doesn’t think the state will allow the district to delay joining CIF, the California federation, another two years, noting the education department is vigorously defending its law against the Trump administration: “They’re not going to fight to uphold the law and say to you at the same time, ‘Okay, you can ignore it for two years.’”

Tahoe-Truckee Unified’s two high schools with athletic programs, which are located about 6,000 feet (1,800 meters) in elevation, compete against both California and Nevada teams in nearby mountain towns — and others more distant and closer to sea level. If the district moves to the California federation, Tahoe-Truckee Unified teams may have to travel more often in bad weather across a risky mountain pass — about 7,000 feet (2,100 meters) in elevation above a lake — to reach schools farther from state lines.

Coleville High School, a small California school in the Eastern Sierra near the Nevada border, has also long been a member of the Nevada association, said Heidi Torix, superintendent of the Eastern Sierra Unified School District. The school abides by California law regarding transgender athletes, Torix said.

The school has not been similarly ordered by California to switch where it competes. The California Department of Education did not respond to requests for comment on whether it’s warned any other districts not in the California federation about possible noncompliance with state policy.

State Assemblymember Heather Hadwick, a Republican representing a large region of northern California bordering Nevada, said Tahoe-Truckee Unified shouldn’t be forced to join the CIF.

“I urge California Department of Education and state officials to fully consider the real-world consequences of this decision—not in theory, but on the ground—where weather, geography, and safety matter,” Hadwick said.

Rec Sports

Hospital demolition begins at site of Detroit’s new soccer stadium

Dec. 19, 2025, 4:09 p.m. ET

Detroit — Wrecking crews on Friday started work to transform a long-vacant eyesore on the city’s west side into a 15,000-seat professional soccer stadium that officials hope will spur economic growth and further solidify Detroit’s reputation as a sports mecca.

City officials and leaders with the Detroit City Football Club gathered on a chilly Friday afternoon at the corner of Michigan Avenue and 20th Street, the site of the former Southwest Detroit Hospital, to celebrate a milestone step for the nearly $200 million project.

Rec Sports

‘Scott Hancock Court’ Celebrates JV Coach’s 50 Years Building Up Cheboygan Hoops

Editor’s Note: An extended version of this article appeared originally in the Cadillac News in March. Since then, Allen has been inducted into the Basketball Coaches Association of Michigan’s Hall of Honor in October and is wearing the striped shirt again this basketball season, officially his 50th year.

CADILLAC – Bill Allen’s story is similar to that of many area sports officials, particularly those officials who have been active for many years.

A background in sports, typically playing team sports while growing up, combined with a desire to continue to be involved after high school or college, coupled with an inner urge to be part of the solution – these characteristics find a natural outlet for those brave souls who choose to be officials. and these traits are nearly always part of the make-up of the officials who receive high grades for their efforts and serve capably for many years.

Allen, of Cadillac, would not say this about himself. But he is one of those officials whom coaches are glad to see on the floor because they know they’re getting someone who will be fair and consistent. The same could also be said of Allen when he was umpiring, though he doesn’t work the diamonds anymore.

As Allen can tell you as he enters his 50th year wearing the striped shirt on the hardwood, officiating is a demanding vocation – and it is rewarding at the same time. It requires the right temperament as well as an above-average level of mental and physical fitness, especially as age makes its inevitable demands. It requires the ability to make decisions quickly, sometimes under very stressful conditions. It requires the ability to face criticism, sometimes expressed loudly or very loudly. It requires the ability to be a peacemaker at times and also the willingness not to hold grudges or become petty.

For those like Allen who have what it takes, those who are up to the challenges and the rigors that officiating requires from an individual, there is a deep satisfaction in knowing they are making a positive difference.

“I think that’s a common thread among all the officials, whether it’s basketball or baseball or softball,” Allen said. “You obviously want to do your best, but you want to manage the game in a way that helps it to flow the way it should flow and enables everyone, the players and the coaches and the fans, to get the most out of it.

“It’s an old cliché but it’s true: The best officials are the ones you hardly notice. If you can officiate a game and walk through the crowd afterward and no one recognizes you, then you’ve probably done your job pretty well that game. That’s what every official strives for.

“You’re never going to get every call right, and you have to be willing to accept that going into it,” he added. “But you know the rules and apply the rules the best you can, you put yourself in the best position to make the calls, especially in basketball, and you call it the way you see it.

“You’re never going to get every call right, and you have to be willing to accept that going into it,” he added. “But you know the rules and apply the rules the best you can, you put yourself in the best position to make the calls, especially in basketball, and you call it the way you see it.

“Are you always right? No. But if you put yourself in the right position and make the call you believe is correct, you can live with that and normally the coaches can too, even if they’re angry about a particular call in the moment.”

Allen, like most officials, was an athlete himself growing up in Traverse City and playing multiple sports for what was then known as Traverse City High School, the largest high school in Michigan in the early 1970s. By his own admission, he wasn’t one of the top stars in basketball and baseball but he was a good, reliable player for his coaches and a dependable teammate who loved the atmosphere of the arena during each season as well as the sense of achievement that the act of competing brought out in him like nothing else.

“I was pretty athletic growing up, but not a great athlete at Traverse City High School,” he said. “I was good enough to make the teams, but I wasn’t what you would call an impact player. A lot of officials have the same kind of background as mine. Maybe we weren’t the greatest players, but we still enjoy sports and we like being part of the action.”

It was during his final two years at Michigan State during the mid-1970s that Allen received his start in officiating.

“In my junior year at Michigan State, one of the fellows I roomed with did assignments for the intramural programs at the college,” he said. “Everything from touch football to basketball to slow-pitch softball. He told me to take the officiating class and he would assign me to games, and that’s how it all started 50 years ago.”

Allen jumped into the world of officiating eagerly with both feet, working a sporting event “nearly every night” at MSU.

“I would go to school during the day, ref at night, and do it again the next day,” he recalled.

“There were so many contests, maybe thousands, that I got to work with a number of other officials. Tim McClelland, who later became a Major League umpire and made the illegal pine tar bat call against George Brett, was a colleague back then. It was a lot of good experience and good mentoring and laid a great foundation for what turned out to be ahead.”

Allen initially earned a degree in criminal justice, graduating from Michigan State University in 1977, and worked in the field of corrections for a period of time before his love of baseball and a sense of personal confidence in his potential to officiate at a higher level prompted him to attend a school for prospective umpires in Daytona Beach, Fla.

That didn’t quite work out, but Allen was not deterred. He changed his career plans from criminal justice to education, and the switch would also lead to abundant opportunities for officiating down the road not just on the baseball and softball diamonds but the basketball court as well.

“When I didn’t get picked (for umpiring), I went back to school to earn my teaching certificate and a graduate degree in history with the goal of becoming a teacher at Cadillac,” he explained. Allen’s wife Sue already was employed as a teacher with the school district.

Bill’s goal at that point was to join Sue as a member of the faculty, as a social studies teacher, and that’s just what happened. Bill served for 26 years in the classroom before retiring along with Sue 12 years ago.

“I viewed Cadillac schools as a great organization to work for as a teacher before I got hired there, and I was right,” he said. “I wouldn’t trade my years at Cadillac for anything. Susie and I both thoroughly enjoyed our years there.”

In conjunction with teaching, Allen continued to officiate basketball in the winter and baseball in the spring and summer. He umpired a lot of men’s summer league softball games through the years and grew to love in particular working the games under the lights at Cadillac’s Lincoln Field.

In conjunction with teaching, Allen continued to officiate basketball in the winter and baseball in the spring and summer. He umpired a lot of men’s summer league softball games through the years and grew to love in particular working the games under the lights at Cadillac’s Lincoln Field.

He also became a registered official with the MHSAA and has continued in that role, though he decided to hang up his umpire cleats a few years ago.

“I registered with the MHSAA while I was still in Lansing,” he said. “The first place I ever did a sanctioned event was in Perry, Michigan. I had barely enough (umpiring) equipment and I’m sure I looked like a real yahoo out there, but I got through it.”

After coming to Cadillac, Allen met Dave Martin, who was an active official and a fellow teacher at Marion, and Martin became his first “crew chief.”

“They needed some JV officials and I got signed up and was off and running,” Allen recalled. “That’s how you got into it back then. You found a crew and the crew chief assigned you some games, and you were evaluated. As long as they liked you and liked what you were doing, they kept you around.”

Allen expressed admiration and appreciation for Martin and also the late June Helmboldt from Lake City, another crew leader “who had a great perspective on the game.”

Allen served as a crew chief himself for a long time and has built rewarding relationships with fellow officials through the years. He has worked many games with Penny McDonald of Cadillac, another longtime official who has earned much respect for her consistency and quality of work in multiple sports over the decades. Allen, in a reversal of roles, is the one receiving assignments from McDonald these days.

Bill Bartholomew is another longtime officiating partner with whom Allen has worked many games over the years and for whom Allen has great respect. This school year, in fact, marks Bartholomew’s 51st year as an official. There are a few others from northern Michigan who have stood the test of time and have passed the 50-year service milestone, such as Paul Williams of Mesick, Tom Post and Mike Muldowney of Traverse City, Tom Johnson of Gaylord, and Dan Aldrich of Charlevoix. All of these, Allen said, are a credit to the craft of officiating and have earned the respect they receive.

Allen also has fond memories of working frequently through the years with Don Blue of Falmouth and Jill Baker-Cooley of Big Rapids, who was chosen for the MHSAA’s prestigious Vern L. Norris Award in 2018.

“I was there when Don and Julie and Penny all got their start in officiating, and they all found their skill set and became excellent officials,” Allen said.

Bill is included in the 50-year milestone group of basketball officials now that the 2025-26 season is underway. He is pleased that he has been able to maintain his longevity; as to the future, he is ready and willing to keep going.

“As long as I’m healthy and can do it properly, I hope to continue,” said Allen, who remains physically fit, jogging regularly along with activities including downhill skiing in the winters and golf during the warmer months.

“I’ll know when it’s time to step aside. When I can’t see well enough to judge the baseline and need to rely on my partners more than I should, then it’s time to hang up the whistle and let the younger ones take over. I hope that’s not for a while though.”

Mike Dunn is a sportswriter for the Cadillac News and the sports editor of the Missaukee Sentinel weekly. He has won numerous awards through the Michigan Press Association as well as the Michigan Associated Press.

PHOTOS (Top) Cadillac’s Bill Allen, shown here following a varsity girls basketball game in February in Evart, is in his 50th year as an MHSAA registered official. (Middle) Allen waits at the baseline for action to resume. (Below) Allen talks casually with McBain Northern Michigan Christian boys assistant coach Terry Pluger prior to the start of the varsity game with Buckley on Dec. 8. (Photos by Mike Dunn.)

Rec Sports

Youth Sports in Philly Are Uneven — and the Gaps Are Growing

Longform

Decades of uneven investment have left Philly kids playing at a disadvantage, with consequences that stretch far beyond the game.

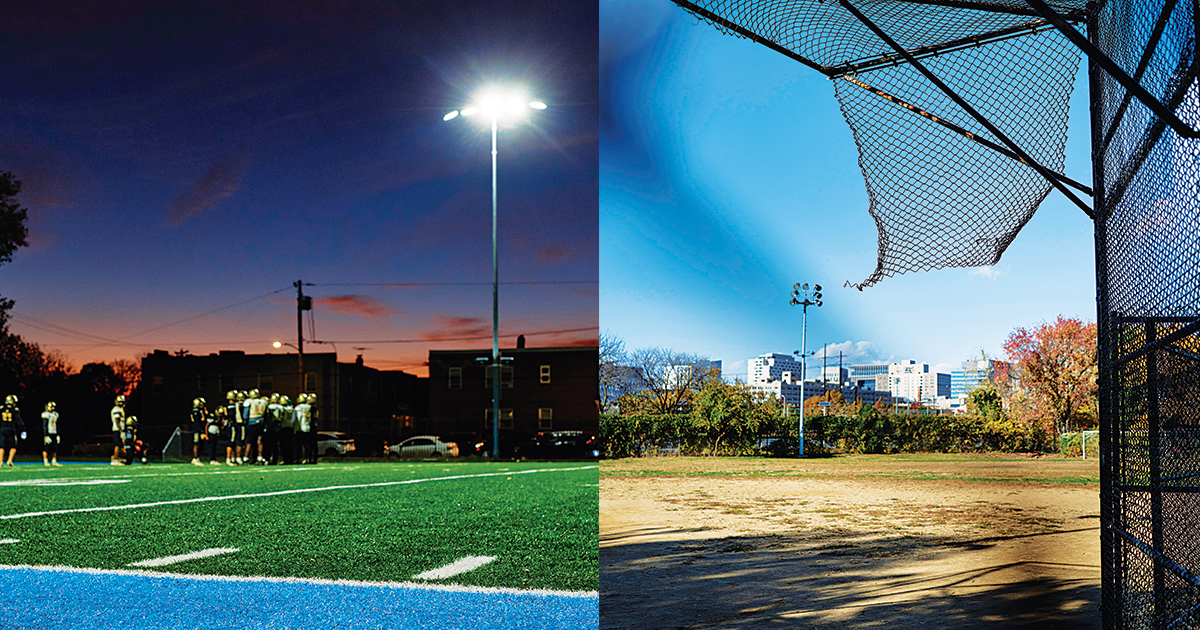

Field at Vare Recreation Center / Photography by Gene Smirnov

It is a warm September evening at the sparkling new $21 million Vare Recreation Center at 26th and Moore streets, home to the Sigma Sharks youth sports program. Neighborhood children romp around a sprawling playground as a DJ spins oldies, while three different football teams practice in different corners of the center’s multipurpose football/ soccer field. As teams of various ages run plays, younger siblings — the next generation of Sharks — dart about.

Before the new gridiron opened in late July, the six Sigma Sharks teams practiced and played as they always had, on an unkempt grass field strewn with rocks and dotted with large dirt patches and the occasional pile of dog feces. “It was dirty, and looked like it wasn’t taken care of,” says Caleb Williams, a member of the Sharks U13 (under-13) team and an eighth-grader at Christopher Columbus Charter School.

Not anymore. The new Vare field is a pristine vivid green, surrounded by a four-foot-wide bright blue border. “We call it the water,” says Tariq “Coach T” Long, who directs the U8 squad. “Once you cross the water, you’re in with the Sharks.”

And that’s a pretty good place to be these days. The Sigma Sharks, who have been around since 1992, sponsor the football teams plus a cheerleading program and four basketball squads, serving more than 300 kids. Sharks president Anthony Meadows says they love the new facility, which also boasts two gleaming indoor basketball courts. “When the kids saw it for the first time, they lost their minds,” says Kevin Mathis, a coach since 1997. (He calls himself “the longest-tenured Shark.”)

Since Vare can’t accommodate all six teams at once, some still practice and play at Smith Playground at 24th and Jackson. Meadows calls it “adequate.” Tanisha Perry, who brings her eight-year-old twin sons from West Philly to play, disagrees. Smith is dirty, she says, and “attracts the wrong crowd.” Vare, on the other hand, is safe, with clean bathrooms and omnipresent staff members.

“I want to be here, always,” she says.

You can see why. In Philly, Vare is a unicorn of a facility that materialized through a combination of funding from the city’s soda tax and a relentless champion in the form of City Council President Kenyatta Johnson. Johnson worked with former Philadelphia Eagle Connor Barwin’s Make the World Better Foundation on the project, which is in his district.

Most city districts (and rec centers, and kids) aren’t quite this lucky. A 2023 study by Temple University, commissioned by Philadelphia Parks and Recreation and managed by the Philadelphia Youth Sports Collaborative (a nonprofit consortium of youth sports providers and advocates that provides resources, support, and funding), looked at more than 1,400 sports facilities managed by Parks and Rec. Sixty percent of them were rated below or far below average. Eighty percent of athletic fields the kids play on aren’t stand-alone fields, but the outfields of baseball diamonds. On top of that, the Temple study found, facilities in neighborhoods with a larger percentage of white residents were of a higher quality.

It’s very much a two-tiered system. There’s a big gap between them.” — Beth Devine, executive director of the Philadelphia Youth Sports Collaborative

Zoom out a little more, though, and you see that that depressing inequity pales in comparison to the big and growing gulf between the youth sports climate in the city and that in many suburbs, where the fields, facilities, and infrastructure are … well, an entirely different ballpark. “In the suburbs, it’s not even a second thought,” says Meadows. “Kids just go to the fields and throw the ball around. Even if it’s a grass field, it’s nice. In the city, you get overused grass and dirt. And the turf fields are often locked up.”

“It’s very much a two-tiered system,” says Beth Devine, executive director of the PYSC. “There’s a big gap between them.”

She’s right about this … and then some. By now, we all know that youth sports as a whole are only getting more professionalized and more expensive as time rolls on, and that money is a real — and quickly expanding — fault line in and barrier to the world of kids athletics. (A July New York Times story about this very topic cited an Aspen Institute finding that the average U.S. sports family spent $1,016 on its child’s primary sport in 2024 — a 46 percent hike since 2019.) And the stakes of access to athletics are even higher than you might think — and affect more people than just kids and their families. Studies indicate that kids who play sports are better at problem-solving and self-regulation, and, as the Temple report showed, violent crime rates drop in neighborhoods that have youth sports facilities. The better the condition a field or court is in, Devine says, the less crime there is around it — across all types of neighborhoods.

Currently, only 25 percent of kids from U.S. households with annual incomes below $25,000 participate in youth sports, compared to 44 percent of kids from families with annual incomes greater than $100,000 — which makes it tough for sports to be any kind of great equalizer. Add to that the billionaires and private equity firms trying to get a piece of America’s $40 billion youth sports business, founding commercialized camps and leagues and tournaments that compete with and pull talent from even the most moneyed, polished suburban rec teams. All of which means that the chasm between the typical city neighborhood rec team and everyone else is only growing.

The statistics — and what they portend — can be overwhelming. It doesn’t seem like that’s going to change anytime soon.

But then … there’s Vare. Not as fancy as some of the more elite facilities you can find in the ’burbs, with a program not as structured or rigorous or polished — but a game-changer for the kids who play there. “A facility in their neighborhood that kids can call home,” as Meadows says.

“I want this to be normal for everybody,” he adds.

Which makes you think: In a city that loves and understands the value of its sports as well as Philly does — a city that produced Dawn Staley, Wilt Chamberlain, Mo’ne Davis; a city with rec teams that are out there winning championships and tournaments; a city with five (soon six) professional teams — why can’t it be the norm for everybody? Or maybe the more apt question right now, as we stare down a year that’s going to bring the world to our stoop to watch the World Cup, a PGA championship, the Major League Baseball All-Star Game, and the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, is this: How might we make it so, before the opportunity gaps — for the kids, for our city — yawn into infinity?

•

For eight years, Amos Huron has led the Philadelphia Youth Organization, which was founded in 1990 and encompasses the Anderson Monarchs program and its soccer, baseball, softball, and basketball teams. He believes the baseball/softball field at the Marian Anderson Rec Center — which the Monarchs also use as a multi- purpose field — is “probably the best in the city.” He’s likely right: When you walk by the field at 18th and Fitzwater, it’s hard to miss the gleaming, pristine outfield, complete with a warning track and bright yellow foul poles. The 3.4-acre facility also boasts basketball courts inside and out, and room for boxing and martial arts. There’s even an indoor baseball training facility, thanks to an assist from former Phillies star Ryan Howard a decade ago.

It’s still not close to many of its suburban counterparts.

Some 20 miles away, the 725 kids of the Newtown-Edgmont Little League play on seven grass diamonds, three of which have lights. The 15-year-old, 10,000-square-foot indoor Flanigan Center, part of the complex, was recently renovated and allows for winter workouts for NELL players and high school teams from the city and suburbs. An army of volunteers, unpaid coaches, and parents help keep the place running, as do local business sponsors: Levels range from $500 a year (Field Level Sponsor) up to $1,500 (Elite Level Sponsor, which comes with a large sign in the Flanigan Center and two baseball field signs). Even the snack bar is top-tier. “Some people eat there versus the local pizza place,” says coach and former president Daren Grande.

Not far from the NELL baseball universe, the Radnor-Wayne Little League, which will turn 75 in 2027, operates “at least” 12 fields that it leases from Radnor Township and its school district and serves between 900 and 1,000 kids in its baseball and growing softball leagues, according to president Tom McWilliams. Worth noting is that registration fees aren’t much different from a lot of what you see with leagues in the city. Those vary, but seem to hang between $100 and $250; Radnor-Wayne’s fees sit between $150 and $195, and NELL’s is $200.

On paper, Philly has far more assets than either of these townships, with 259 different city locations encompassing more than 1,500 fields and courts. But with all the kids across the city who play on one team or another (some 40 to 45 percent of Philly youth participate in “some structured activity program,” says Philly Parks and Rec director of youth sports Mike Barsotti), it’s not enough to meet the demand. In fact, access is the first problem many leagues face: Competition from adult leagues, travel outfits, high school teams — St. Joe’s Prep’s football squad has practiced on the Philly Blackhawks Athletic Club field in North Philly; Universal Audenried Charter High School practices at Vare — and other neighborhood programs creates scheduling and permitting challenges. The city’s permit process favors neighborhood organizations, but if they don’t register in time, other groups get the chance to sign up (and they’re usually more organized and quicker to fill out requests, says Barsotti). And when new fields open, they reach capacity almost immediately. At the South Philadelphia Super Site turf football field at 10th and Bigler, games are scheduled to the minute during the season, says Adam Douberly, a father to three rec-league athletes. Kids get one hour, exactly, on the fields, playing times vary, and games can end as late as 10 p.m.

Even the popular 1,200-player Philadelphia Dragons Sports Association (formerly the Taney Youth Baseball Association, home to the team that played in the 2014 Little League World Series), which recent president John Maher says has “a relatively affluent demographic, mostly in Center City,” can’t find sufficient field space, and “100 percent” has facility envy when it faces suburban teams in District 19 Little League competition. (Right now the Dragons’ biggest challenge, he says, is finding fields for its burgeoning coed flag football program.)

All of this use (and overuse) helps lead to the second big issue: maintenance. “The city budget to maintain the fields is close to zero, so the fields may start off with grass, but at the end of the season, they are dirt pits,” says Liam Connolly, executive director of Safe-Hub Philadelphia, which provides soccer opportunities for kids ages four to 18 in the Kensington area.