Rec Sports

Looking inward can prevent becoming the ‘crazy sports parents’

Ben Shelton on his relationship with Trinity Rodman

American tennis star Ben Shelton talks about the launch of his new relationship with USA soccer’s Trinity Rodman.

Sports Seriously

The “crazy sports parents,” Skye Eddy says, have ruined the experience for everyone.

You know them. They live vicariously through their child. They have unrealistic expectations for him or her as an athlete. Or they are simply so unreasonable that there’s little we can do to help them understand us better.

“As a coach, I’ve had an irrational parent on my team, and it has made my season miserable,” says Eddy, a former USWNT hopeful turned sports parent advocate. “They’ve been taking way too much of my time and energy from the children by asking too many questions. And so as coaches, when we’ve been in those experiences, we say, ‘OK, well, we’re just gonna avoid all parents, because that was a really difficult season.’ ”

Even Eddy, a one-time defensive MVP of the NCAA women’s soccer Final Four for George Mason who later coached on the staff at the University of Richmond, found herself labeled as one of them.

She saw a veil come over the organization’s executive director when she wanted to chat. To him, she was “a crazy parent, complaining about my daughter … I’m like, ‘Oh no, no, no, I’m just here to help,'” she says.

Then the door shut. It was the ignition that launched her passion project, soccerparenting.com, which today has about 43,000 members nationwide. It offers advice, training and encouragement for coaches and parents and youth sports leaders with a goal of helping us understand each other a little better.

From Eddy’s experience and research, the vast majority of parents are not “crazy,” but level-headed folks who just stressed.

“Parenting is stressful these days, like society’s stressful,” says Eddy, 53, a mother of two kids put through the athletic wringer. “You add on a sports experience, and there is a lot.”

Eddy spoke with us about how our soccer parenting, and sports parenting, can improve when we take a more introspective look at ourselves. From the discussion, USA TODAY Sports came with ways we can soothe our stress around our kids’ games and improve the environment in which they are playing.

Your child’s sports journey is unique from your own. Maybe you need to care less about it.

Eddy, a former goalie, reached as high as U.S. women’s soccer player could go in the 1990s, barring making the national team. She played professionally in Italy. She pushes back at the notion that she was living out her own athletic experiences when her daughter, Cali, also became an elite soccer player in high school.

“I loved my athletic career,” Eddy says. “I just didn’t know what to say to her to help her, because our mindsets are so different.

“She was like, ‘I want to play D-I, I want to play D-1,’ and she was getting D-1 interest, but she wasn’t pursuing it. She would not pick up a phone and call the coach. She was struggling with her self-esteem, her confidence around herself as an athlete, and so she really needed coaches calling her. She needed to be built up like that.”

Eddy was seeing things from her own point of view, and what she would have done. In more recent years, she came across a term (“Decoupling”) that would have helped her.

It is associated with a romantic relationship, where two people pull back from their emotional connection but remain friends. It can also apply to teenagers growing into their own identities as athletes.

“It’s sort of like not feeling things so deeply, letting our children dictate the path and us really being OK with it,” she says. “That is the learning, the making the mistakes: Not calling the coach, not eating the right food, or going to the sleepover the night before and playing really badly.

“And I think that because as parents, it’s so easy to feel like the stakes are so high, we try to interject too much.”

But how do we redirect ourselves? The process can start with our actions on the sidelines, and often when our kids are very young.

Your sideline behavior may be relieving your stress but stunting your child’s progress

You may not admit you’re stressed at your kids’ games. But perhaps unintentionally, you are projecting it onto them.

You cheer loudly. You jump up and down on the bleachers. You call to them. You interfere.

“That’s stress,” Eddy says.

Soccer Parenting’s Sideline Project, which helps condition parents on game day, identifies three types of sideline behaviors:

- We’re “supportive” when we sit in attentive silence, cheer after positive outcomes for our child and his or her teammates, and perhaps even a good play from the other team.

- We’re “hostile” when we yell at referees, yell at our child, or even other players. (Keep reading.)

- We may not realize when we’re being “distracting.” This means we’re offering specific instructions to a child. Go to the ball! Get rid of it! Run!

“Distracting behavior serves one primary purpose: To alleviate our stress as parents and coaches,” Eddy says in her Sideline Project online course. “Players should be hearing their teammates and reasonable information from their coach, not their parents.”

In the video, she demonstrates the Stroop Effect, named after an American psychologist who measured selective attention, processing speed and how interference affects performance.

She has an interactive exercise using colors to illustrate how your children feel when they are concentrating in a game and adults interrupt them. I hitched when I did it.

“There’s a lag,” Eddy says. “This moment of interruption. That is how your child feels when they are playing, concentrating on the technical skill and what their decision is going to be, and they hear your voice telling them to shoot or pass.”

Instead, a good youth coach won’t distract, but give a subtle cue – a nod, a whistle, a finger point or a closed fist – to trigger something they worked on in practice.

“Whatever it is that we’re screaming, we’re taking away their learning opportunity,” Eddy says.

‘Do you realize I’m 13?’ If we focus on being less distracting, the truly hostile parents stand out

Cali was a tough defender. So tough, apparently, that she once came home from road club soccer tournament and reported: “Another parent from the other team was sitting on the sideline, flicking me off. She just sat there, giving me the finger, staring right at me.

“I said, ‘You do realize I’m 13 and you’re a grown adult, right?'” she told her mom.

Eddy estimates that 2% of the youth sports ecosystem, perhaps one parent per team, are these hostile ones. Many of us are merely distracting, a quality we can correct.

U.S. soccer recently updated a referee abuse prevention policy for youth and amateur soccer. Suspensions from two games to lifetime bans are now issued if you belittle, berate, insult, harass, touch or physically assault sports officials.Report the abusers and get them thrown out. They are not part of our experience.

I like to sit with the opposing team’s fans when my sons are pitching in their baseball games. While I get a different video angle, I meet new people and feel and hear their emotions. Sometimes I just listen to them. It helps remind me why we are all in this.

“We care so much about sport because of the connection,” Eddy says.

We can communicate easier with coaches if both sides respect boundaries

Cali quit soccer for short time when she was eight. She was bored.

Players were standing in lines. They did the same warmup at every practice. They weren’t even given adequate instruction, Eddy thought. It was labeled as an advanced development program.

When she asked other parents what they thought of the environment, they were fine with it.

“It struck me that until parents understand what a good learning environment looks like, to lead to player inspiration and joy and really giving kids a connection to sport, then we’re really going to be missing a big part of the solution when it comes to improving youth sports,” she says.

“The last thing we want to do is be perceived as one of these irrational parents, so we’re not curious, we don’t ask questions, we don’t listen to our instincts, we don’t follow up when we when we probably should, because we don’t want to be perceived to care too much when there’s a big difference between being irrational and caring.”

When she tried to speak up and was rebuffed, she became a youth coach. And soccerparenting.com was born.

One of its foundational principles is to encourage coach and parent interaction, with clear and appropriate boundaries.

Some suggested parameters a coach can use:

The door is open to chat … When your kid comes home from practice in a bad mood or doesn’t want to go the next day; if he or she is having trouble playing a particular position; if you don’t fully understand the scoring system or rules of the sport.

The door is closed to chat … If you have a complaint about another player that doesn’t involve a safety issue; if you’re wondering why the coach made a tactical decision; if you don’t respect a coach’s time and want to have a long conversation after practice. (You can schedule one instead.)

“We see the correlation between parents having more understanding and the children’s experience getting better, and then therefore clubs and coaches having to get better,” Eddy says.

Coach Steve: Three steps to dealing with a ‘bad’ coach

Be proactive, and intentional, about the way you handle stress

Even when we feel we have things under control during games, sometimes we don’t. Eddy laughs about once walking across the field with a plan in her head of what she would say to Cali. It didn’t involve the game. Instead, in the heat of the moment, she said: “You really need to work on your left foot.”

“Where did that come from?” she says. “I had zero intention of saying that. It just poured right out of me.”

When I posed a question on social media about how we can be better soccer parents, Palmer Neill, of Dallas, told me: “Basically, when you feel like doing something at a game or practice other than cheer or clap … just don’t do it. Let the coach be the coach and let the ref, ref. You don’t have (a) role. Life gets a lot easier when you realize this.”

But we can also recognize that sometimes we slip, too, and take precautions. When Neill barks to his 10-year-old son to get onsides, or about an opponent’s hand ball, he sits back in his chair and doesn’t get up. He tries to stay seated during the game.

“It seems to give me one extra second to think before I sit up (or stand-up) and yell,” he says.

Our own education and reflection, Eddy says, can relieve stress.

Know the rules (and recent modifications to them). Know your kid’s goals in sports. Be curious, not upset, when other kids have more skills than yours.

Perhaps it’s the Relative Age Effect, where young athletes born earliest among their age grouping are faster and stronger. Or that those kids move better because they play other sports or have more free play outside with friends and have better functional movement skills.

We can put our own sports paths into better context, too.

Coach Steve: MLS NEXT youth soccer rankings emphasize development over wins

Remember they are still kids, even when they’re creeping toward adulthood. There is satisfaction in watching who they are becoming.

What did you do when you were eight? Twelve? Sixteen?

When Eddy thinks about it, she liked to socialize at the local skating rink.

She only trained twice a week with her soccer team. On off days, she rode to a local park and kicked the ball into a piece of plywood against a fence. She would dive at the rebounds.

She used to wonder if Cali, who came back to soccer on her own terms, was getting enough reps on her own.

“What would I have been doing if I was in intense practices for an hour and a half four days a week, plus traveling to a lot in the games?” Eddy says. “Would I still have been doing that? Likely not.”

In today’s world, it feels like kids sports matter a lot more. Maybe they do when we have more opportunities to play in front of college coaches. Maybe they don’t when we play rec soccer, like Eddy’s son, Davis, did, and parents screamed when he missed a shot.

Davis, now a junior in college, had a better experience playing at a small high school.

“Having that outlet for sport was really important to his development, just as a person, and getting some space and, kind of way to blow off some steam as a student,” she says.

Cali decided to work at a sleepaway camp in Maine during the summer before her junior year, a crucial one for college recruiting. She became a Division III All-American and now works for the Columbus Crew.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s so hard for you,’ but not saying that out loud,” Eddy says. “That was a really important capstone to a really important thing in our life. Yet, she really missed a lot of opportunities, and there were consequences of that. We just need to make sure that it’s our child’s voice that we’re hearing.”

We are when we let them lead the way, to choose friends over sports when they wish, and to have those sleepovers. Well, maybe not the sleepovers.

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for two high schoolers. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.

Got a question for Coach Steve you want answered in a column? Email him at sborelli@usatoday.com

Rec Sports

Miller Park funding began on this day in 1996

MILWAUKEE, Wis. (WMTV) -On Jan. 3, 1996, Wisconsin residents and visitors began funding construction of what would become Miller Park through a new sales tax.

The funding mechanism was part of state legislation passed in 1995. The bill included a $250 million preliminary budget for design, construction and development of the Milwaukee Brewers stadium.

The legislation allowed a one-tenth of a percent sales tax to help pay for the stadium in Milwaukee. The bill also required any major league baseball team using the facility to contribute to youth sports organizations annually and mandated general seating in the stadium be smoke-free.

Construction on what is now American Family Field began Nov. 6, 1996. The stadium opened five years later in 2001 as Miller Park, a name it held until 2020.

Click here to download the WMTV15 News app or our WMTV15 First Alert weather app.

Copyright 2026 WMTV. All rights reserved.

Rec Sports

As more youth sports professionalize, efforts around U.S. try to keep kids from burning out – The Press Democrat

ESCONDIDO — Like many mothers in Southern California, Paula Gartin put her twin son and daughter, Mikey and Maddy, into youth sports leagues as soon as they were old enough. For years, they loved playing soccer, baseball and other sports, getting exercise and making friends.

But by their early teens, the competition got stiffer, the coaches became more demanding, injuries intervened and their travel teams demanded that they focus on only one sport. Shuttling to weekend tournaments turned into a chore. Sports became less enjoyable.

Maddy dropped soccer because she didn’t like the coach and took up volleyball. Mikey played club soccer and baseball as a youngster, then chose baseball before he suffered a knee injury in his first football practice during the baseball offseason. By 15, he had stopped playing team sports.

Both are now in college and more focused on academics.

“I feel like there is so much judgment around youth sports. If you’re not participating in sports, you’re not doing what you’re supposed to be doing as a kid,” Gartin said. “There’s this expectation you should be involved, that it’s something you should be doing. You feel you have to push your kids. There’s pressure on them.”

Youth sports can have a positive effect on children’s self-esteem and confidence and teach them discipline and social skills. But a growing body of recent research has shown how coaches and parents can heap pressure on children, how heavy workloads can lead to burnout and fractured relationships with family members and friends, and how overuse injuries can stem from playing single sports.

A report published by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2024 showed how overuse injuries and overtraining can lead to burnout in young athletes. The report cited pressure by parents and coaches as additional risk factors. Another study, in the Journal of Sport Social Issues, highlighted how giving priority to a win-at-all-costs culture can stunt a young athlete’s personal development and well-being. Researchers at the University of Hawaii found that abusive and intrusive behavior by parents can add to stress on athletes.

Mental health is a vast topic, from clinical issues like depression and suicidal thoughts to anxiety and psychological abuse. There is now a broad movement to increase training for coaches so they can identify signs and symptoms of mental health conditions, said Vince Minjares, a program manager in the Aspen Institute’s Sports Society Program. Since 2020, seven states have begun requiring coaches to receive mental health training, he said.

Domineering coaches and parents have been around for generations. But their pressure has been amplified by the professionalization of youth sports. A growing number of sports leagues are being run as profit-driven businesses to meet demand from parents who urge their children to play at earlier ages to try to improve their chances of playing college or pro sports. According to a survey by the Aspen Institute, 11.4% of parents believe that their children can play professionally.

“There’s this push to specialize earlier and earlier,” said Meredith Whitley, a professor at Adelphi University who studies youth sports. “But at what cost? For those young people, you’re seeing burnout happen earlier because of injuries, overuse and mental fatigue.”

The additional stress is one reason more children are dropping out. The share of school-age children playing sports fell to 53.8% in 2022, from 58.4% in 2017, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health. While more than 60 million adolescents play sports, up to 70% of them drop out by age 13.

While groups like the Aspen Institute focus on long-standing issues of access and cost in youth sports, combating mental health problems in young athletes is an emerging area. In recent years, professional athletes like Naomi Osaka and Michael Phelps have shined a light on the issue. But parents who want to teach their children the positive parts of playing sports are finding that some of the worst aspects of being a young athlete are hard to avoid.

That was apparent to the parents who took their sons to hear Travis Snider speak at Driveline Academy in Kent, Washington, one Sunday last spring. Snider was a baseball phenom growing up near Seattle and was taken by the Toronto Blue Jays in the first round of the 2006 MLB draft.

But he finished eight unremarkable seasons as an outfielder and played his last major league game at 27. While attempting a comeback in the minor leagues, he worked with a life coach to help him make sense of why his early promise fizzled. He unearthed childhood traumas and unrealistic expectations on the field.

In a playoff game as an 11-year-old, he had had a panic attack on the mound and was removed from the game.

Though he reached the highest level of his sport, Snider felt as if distorted priorities turned baseball into a burden, something he wanted to help others avoid.

Last year, he started a company, 3A Athletics, to help children, parents and coaches develop healthier approaches to sports that include separating professional aspirations from the reality that most young athletes just want to get some exercise and make friends.

“We as a culture really blended the two into the same experience, which is really toxic for kids as they’re going through the early stages of identity formation,” Snider said. “You have a lot of parents who are sports fans that want to watch youth sports the same way they watch pro sports without recognizing, ‘Hey, the thing I love the most is out there running around on the field.’”

He added, “We’ve got to take a step back and detach from what has become normalized and what kind of vortex we get sucked into.”

Driveline Academy, an elite training facility filled with batting cages, speed guns, sensors and framed jerseys of pro players, might be the kind of vortex Snider would want people to avoid. But Deven Morgan, director of youth baseball at Driveline, hired 3A Athletics to help parents and young athletes put their sport in context.

“It’s part of a stack of tools we can deploy to our families and kids to help them understand that there is a structural way that you can understand this stuff and relate to your kid,” he said.

“We are going to get more out of this entire endeavor if we approach this thing from a lens of positivity.”

During his one-hour seminar, Snider and his partner, Seth Taylor, told the six sets of parents and sons how to navigate the mental roadblocks that come from competitive sports. Snider showed the group a journal he kept during the 2014 season that helped him overcome some of his fears, and encouraged the ballplayers to do the same.

“It’s not just about writing the bad stuff,” he said. “The whole goal is to start to open up about this stuff.”

Taylor took the group through a series of mental exercises, including visualization and relaxation techniques, to help players confront their fears and parents to understand their role as a support system.

His message seemed to get through to Amy Worrell-Kneller, who had brought her 14-year-old son, Wyatt, to the session.

“Generally, there’s always a few parents who are the ones who seem to be hanging on too tight, and the kids take that on,” she said. “At this age, they’re social creatures, but it starts with the parents.”

Coaches play a role, too. The Catholic Youth Organization in the Diocese of Cleveland has been trying to ratchet down the pressure on young athletes. At a training session in August, about 120 football, soccer, volleyball and cross-country coaches met for three hours to learn how to create “safe spaces” for children.

“Kids start to drop out by 12, 13 because it’s not fun and parents can make it not fun,” said Drew Vilinsky, the trainer. “Kids are tired and distracted before they get to practice, and have a limited amount of time, so don’t let it get stale.”

Coaches were told, among other things, to let children lead stretches and other tasks to promote confidence. Track coaches should use whistles, not starting guns, and withhold times from young runners during races.

“We’re trying not to overwhelm a kid with anxiety,” said Lisa Ryder, a track and cross-country coach for runners through eighth grade. “CYO is not going to get your kid to be LeBron.”

Rec Sports

Mercer County CYO basketball results – Trentonian

The Mercer County CYO basketball leagues have had some interesting games leading into to the Christmas break.

In a hotly-contested game between St. Raphael’s and St. Paul’s in the Boys’ Varsity Division as St. Raphael’s used 17 points from Dominic O’Rourke to earn the 42-36 victory.

St. Paul’s loves those close games as it edged St. Ann’s 32-29 as Demetria Bouroutis led the way with 14 points.

Evan Rogers led the way for St. Gregory’s Blue with 16 points as it doubled up St. Paul’s 50-25 and St. Ann’s took care of St. James White, 43-19 behind Chandler Brown’s 14 points.

Brown was on target when St. Ann’s stopped St. Paul’s 34-23 as he netted 21 points.

St. James White got a win over St. Gregory’s White, 34-13 as James McFarlane poured in 12 points.

Gianni Coopla led St. John’s to a pair of wins as he had 22 points in the 37-21 victory. Over Our Lady of Sorrows and Coopla stayed hot with 21 points in St. John’s 45-13 win over St. Gregory’s White.

The Boy’s JV Division saw St. Raphael’s Gold defeated St. Raphael’s Blue 23-10 as Dylan Cacciabadel had seven points.

St. Ann’s got the best of St. Raphael’s Blue with a 20-13 win as Hank Little had nine points.

In another of those in-house battles, St. Gregory’s Blue took St. Gregory’s Gary, 40-9 as Vincenzo Dimorino scored 12 points.

The struggles continued for St. Raphael’s Blue as St. Paul’s behind Matthew Vannozzi’s 16 points took a 25-17 win.

Grayson Griffis tallied 12 points in leading St. Raphael’s Gold to a 30-16 win over St. Paul’s in the Boy’s Freshman Division and in a St. Gregory’s battle it was the Blue getting 10 points from Antonio Barone to take a 30-8 decision over the White.

St. Gregory’s Blue used Quinn Nemeth’s six points to get past St. Raphael’s Gold, 22-12 and Luke Edwards had six points in St. Paul’s 9-6 win over St. Gregory’s White.

St. Ann’s defeated St. Raphael’s 7-4 as Gabriel Topley and Jackson Coe each had two points.

The Girls’ Varsity Division saw Noel Davis score 15 points to lead St. Paul’s to a 34-30 win over St. Raphael’s.

Linzy Ditta had a great game with 12 points as St. Raphael’s topped St. Paul’s 33-24.

Joselyn Grant tallied nine points as St. Raphael’s notched a 25-9 win over St. Gregory’s White in the Girls’ JV Division.

Addison Woods scored seven points as St. Gregory’s Blue got passed St. Paul’s 15-8.

Over in the Girl’s Freshman Division, it was St. Gregory’s White using six points from Hazel Stuehaen to get past St. Paul’s, 12-4.

Rec Sports

More than 170M youth sports complex proposed for Big Bend

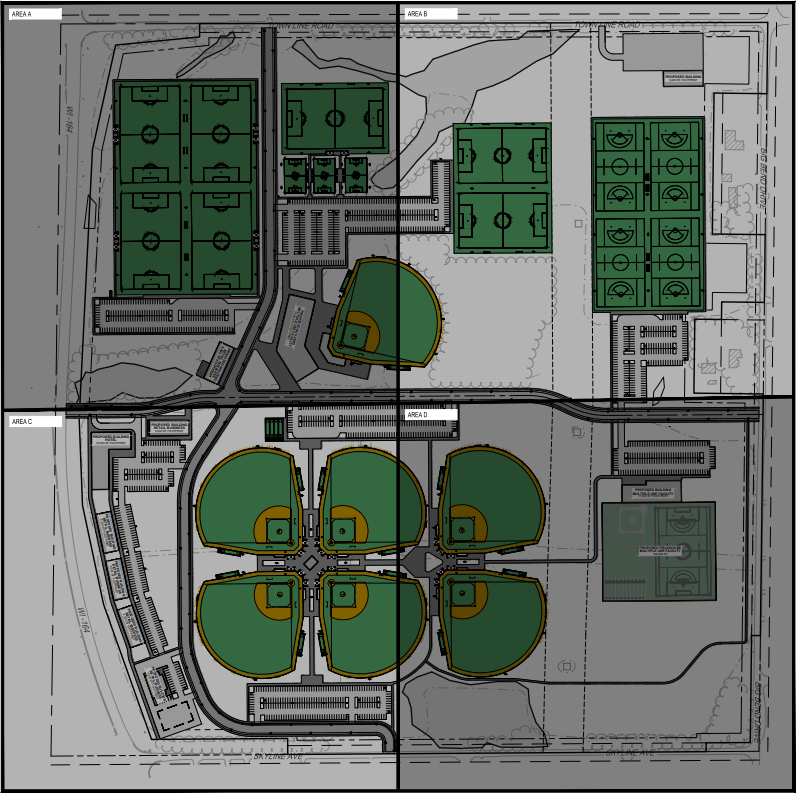

THE BLUEPRINT:

- A more than $175 million youth sports complex is proposed for Big Bend.

- The Breck Athletic Complex will include baseball, soccer, lacrosse fields and a 155,000-square-foot indoor facility.

- The developer requested rezoning 42 acres to facilitate construction.

- A public hearing is set for Jan. 29.

A youth sports complex worth more than $170 million is in play for Big Bend.

The village of Big Bend Plan Commission considered a proposal to turn farmland into a multiphase, mixed-use recreation and hospitality development in Waukesha County. The Breck Athletic Complex will include six turf baseball fields, seven full-size soccer fields, futsal and lacrosse fields, and an indoor turf facility spanning 155,000 square feet for baseball, soccer and lacrosse training, plans showed.

Eric Weishaar, founder and president of Breckenridge Landscape, presented the development to village officials in November 2025. I & S Group, Inc. provided design services.

Kraus-Anderson, the project construction manager, estimated the total construction cost will range between $175 and $225 million, according to a letter from I & S Group. Two major factors that will influence the final cost are a proposed retail area and anticipated upgrades to State Highway 164, plans showed.

The architecture will have a “Colorado Mountain Town” influence throughout eight stages of development, plans showed. Amenities include concessions, restrooms, playgrounds, fitness trails and landscaped plazas. Additional uses include a craft bar and restaurant, banquet hall, hotel, gas station and future retail spaces for visitors and residents.

The development team has requested rezoning 42 acres at the northeast corner of Skyline Avenue and State Highway 164, an agenda showed. The parcel is around 150 acres, but at least 40% of it will be used for green and open space, plans showed.

Located in the far north side of Big Bend, the development is south of homes and open land in the village of Waukesha and west and north of homes in the village of Vernon, plans showed.

Some residents in Big Bend and Vernon spoke up with concerns about the aesthetic of the 70-foot proposed building, potential light pollution and traffic, local outlets reported. The village has a population of nearly 1,500, according to the U.S. Census Bureau; the planned Breck Athletic Complex will provide around 1,500 parking spaces.

There were no residential units included in the development plans.

The village of Big Bend Board of Trustees and Plan Commission will hold a joint public hearing on Jan. 29 to discuss the rezoning.

Rec Sports

Brown Deer youth sports facility project proceeds with site purchase

Jan. 2, 2026, 11:26 a.m. CT

A youth sports facility planned for Brown Deer has taken a step forward with the developer buying the project site for $3.2 million.

Brown Deer Development Partners LLC, an affiliate of Cobalt Partners LLC, bought the site on North Arbon Drive, south of West Brown Deer Road, on Dec. 30.

That’s according to a deed posted online by the Wisconsin Department of Revenue. The mostly vacant site was sold by Brown Deer Master P1 LLC, an affiliate of Royal Capital Group Ltd.

Rec Sports

Hockey vs Trine (St. Cloud Youth Hockey Night) on 1/2/2026 – Box Score

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoRoss Brawn to receive Autosport Gold Medal Award at 2026 Autosport Awards, Honouring a Lifetime Shaping Modern F1

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoStempien to seek opening for Branch County Circuit Court Judge | WTVB | 1590 AM · 95.5 FM

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoPrinceton Area Community Foundation awards more than $1.3 million to 40 local nonprofits ⋆ Princeton, NJ local news %

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoDowntown Athletic Club of Hawaiʻi gives $300K to Boost the ’Bows NIL fund

-

NIL3 weeks ago

NIL3 weeks agoKentucky AD explains NIL, JMI partnership and cap rules

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoTeesside youth discovers more than a sport

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoPRI Show revs through Indy, sets tone for 2026 racing season

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoYoung People Are Driving a Surge in Triathlon Sign-Ups

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoThree Clarkson Volleyball Players Named to CSC Academic All-District List

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoBeach Volleyball Unveils 2026 Spring Schedule – University of South Carolina Athletics