Motorsports

Michael Jordan Hired The Best Sports Lawyer In The Country To Go After NASCAR

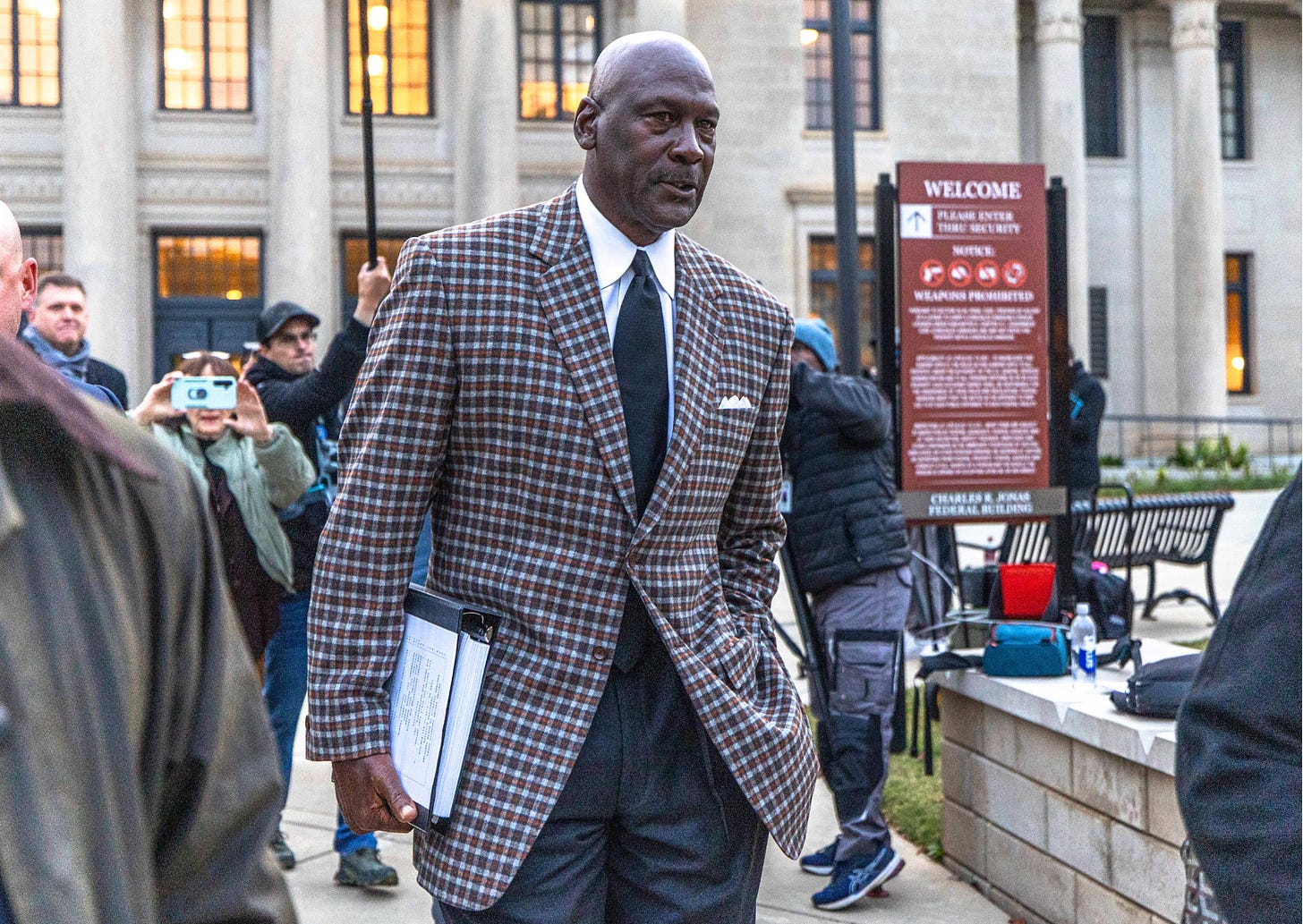

While most media outlets have been fixated on the Paramount-WBD-Netflix deal, Michael Jordan has spent the last week sitting in a Charlotte, North Carolina, courthouse, testifying in one of the most consequential antitrust trials this year.

Here’s what you need to know: Two racing teams, 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports, have sued NASCAR for monopolistic and anticompetitive practices.

Among other things, which we’ll get into, 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports claim that NASCAR has illegally used its monopoly power to control the sport’s financial structure, limiting team revenue and stifling competition through its charter system and other restrictive practices, such as controlling track access and car parts.

Court proceedings can sometimes feel like you are a teenager counting down the minutes for a high school class to end, but antitrust cases are different. The best way to learn how a business or industry really works is to pay attention to an antitrust trial.

Over the last week and a half alone, this trial has provided exclusive access to team and league financials, including annual profit-and-loss statements. For example, we now know how much money Michael Jordan has invested in 23XI Racing over the last five years ($40 million), the average expenses required to run a NASCAR Cup Series car each year ($20 million), how much money NASCAR lost on its three Chicago street races ($55 million), the total amount of money Front Row Motorsports owner Bob Jenkins has lost since entering the sport in 2005 ($100 million), and even how NASCAR strategically moves around its revenue to reduce its on-paper profits.

Plus, like any discovery process, some juicy emails and texts have emerged. NASCAR’s president once called team owner Richard Childress a “stupid redneck” who should be “taken out back and flogged,” while Michael Jordan laughed off the cost of signing a driver by telling his financial advisor, “I have lost that in a casino. Let’s do it.”

For those who aren’t up to speed on NASCAR, 23XI is a racing team owned by Michael Jordan and three-time Daytona 500 winner Denny Hamlin. The team began racing in 2021 and currently runs three cars, winning nine NASCAR Cup Series races.

Front Row Motorsports is another NASCAR Cup Series team. Owned by fast-food restaurant magnate Bob Jenkins, Front Row has fielded cars in the Cup Series since 2005. In total, Front Row has won four races over two decades, with the team’s most notable win coming when driver Michael McDowell won at the 2021 Daytona 500.

While rumors of legal fights have always existed beneath the surface, NASCAR teams have generally avoided confrontation for fear of retribution. At its core, NASCAR is a family business. Bill France founded NASCAR in 1948, and the France family still owns and runs it 77 years later, with four generations occupying leadership roles.

But while others were unwilling to risk the tens (if not hundreds) of millions of dollars that they had invested in the sport through cars, factories, drivers, equipment, and employees, Michael Jordan was uniquely positioned to take on the challenge.

Jordan has more money than he’ll ever need and is a lifelong NASCAR fan. He isn’t scared of what the France family will do because NASCAR isn’t his primary business.

So while every other team signed NASCAR’s 2024 charter agreement (more on that later), 23XI and Front Row refused to sign it. Instead, the two teams joined forces to file an antitrust lawsuit against NASCAR, hiring Jeffrey Kessler to represent them.

If you don’t know Jeffrey Kessler’s name, you have at least seen his work. The 70-year-old lawyer has worked on some of the most significant legal cases in sports history.

Kessler created the NFL, NBA, and NHL player associations. He represented Tom Brady during Deflategate and secured equal pay for the U.S. women’s national soccer team. Kessler also negotiated the free agency and salary cap systems in the NFL and NBA, and just won $2.8 billion in back pay for student-athletes from the NCAA.

Many people seem to believe that this trial will determine whether NASCAR is considered a monopoly, but that’s not accurate. Judge Kenneth Bell has already ruled pretrial that NASCAR holds monopoly power. The jury in this trial is now tasked with determining if NASCAR used that power to engage in anticompetitive conduct.

23XI and Front Row are upset about many things. They don’t like that NASCAR is unwilling to open its books to show teams how much money it is making. They don’t like competing with NASCAR for sponsors, and they also don’t like NASCAR owning roughly 50% of the tracks that the Cup Series races on each year. These tracks receive a percentage of the sport’s TV money, which ultimately winds up back in NASCAR’s hands, and even non-NASCAR-owned tracks are contractually prohibited from hosting non-NASCAR events, making it nearly impossible for a competitor to emerge.

But that’s just one piece of this trial; the bigger issue is NASCAR’s charter system.

Historically, NASCAR treated its teams like independent contractors. Team owners paid for everything, from the cars and drivers to the pit crew and motorhomes. Each team brought its cars to the racetrack, but was never guaranteed a starting spot. Every car had to qualify on speed. If you weren’t fast enough that weekend, you didn’t get to race. If you didn’t get to race, you spent a lot of money just to leave empty-handed.

This was a disastrous business model for teams. Without guaranteed revenue, team financials were unpredictable. There was no incentive to invest in facilities or hire engineering talent, as teams were going out of business just as quickly as they came in.

So, with audiences declining, sponsorships unsteady, and teams folding, NASCAR distributed 36 charters in 2016. As a charter holder, you are guaranteed a starting spot and a share of the prize money from every Cup Series race. Each team can own up to four charters, which can be sold, bought, or leased. If a new team wants to join NASCAR, it must purchase a charter from an existing team. If an existing NASCAR team wants to expand by adding another car, it must buy or lease another charter.

NASCAR distributed these charters to teams for free in 2016. Since then, the price to purchase a charter on the secondary market has increased from $6 million in 2018 to $40 million in 2023. But while NASCAR says its charter program is clear evidence of value creation for its teams, owners disagree. Charters were distributed based on a team’s success from the prior three seasons. So if you are losing millions of dollars every year, didn’t you technically pay for that charter by continuing to show up?

To be clear, team owners were initially happy with the charter program. It was a change they requested and felt provided a step in the right direction. The problem today is that these same owners believe the charter system hasn’t evolved enough.

During the last round of negotiations to extend charters, teams requested several changes. With NASCAR signing a new $7.7 billion media rights deal, teams wanted to receive more than $12.5 million in guaranteed revenue per car. Teams also requested that charters become permanent, providing them with equity value that extends beyond the current rolling 6-year term (and something that NASCAR can’t just take away because it feels like it). Outside of financials, teams also wanted periodic access to NASCAR’s books and a governance vote on business and competitive decisions.

These negotiations lasted more than two years. Based on the evidence presented in court so far, there were heated phone calls, meetings, and emails throughout the process. But when team owners were presented with the final document on a Friday night, NASCAR gave them just six hours to sign it or potentially lose their charter.

The final charter agreement included only a few tweaks from what NASCAR had previously presented. But still, a six-hour deadline on a Friday night meant that many teams couldn’t even have their lawyers review the final 112-page document before signing it, a particularly concerning outcome given the charter extension agreement included language prohibiting teams from filing antitrust lawsuits against NASCAR.

“There was a lot of passion, a lot of emotion, especially from Joe Gibbs; he felt like he had to sign it,” Front Row’s Bob Jenkins testified. “Joe Gibbs felt like he let me down by signing. Not a single owner said, ‘I was happy to sign it. Not a single one.’”

Several teams have since reiterated those comments. Even if they disagreed with the details, some owners had invested hundreds of millions of dollars in the sport and weren’t willing to risk their charter by fighting it. In the end, 13 of NASCAR’s 15 teams signed the agreement, while 23XI and Front Row chose to file a lawsuit instead.

NASCAR is a private business. That means it is not required to report attendance numbers or concession sales, much less its annual revenue or operating profit.

Outside of a few press releases each year or a leaked report, we typically get no insight into how the sport and its teams are performing financially year in and year out.

But that’s what’s so unique about this trial. The discovery process has given us an inside look at the financials — and let’s just say, it doesn’t look great for NASCAR.

According to 23XI’s annual profit and loss statement, the Michael Jordan and Denny Hamlin-owned team has consistently teetered on the edge of profitability. For instance, 23XI Racing reported a $300,000 loss in 2020, a $500,000 profit in 2021, a $2.5 million profit in 2022, a $3.5 million profit in 2023, and a $2.1 million loss in 2024.

Denny Hamlin told the jury this week that it costs $20 million to bring a single car to the track for all 38 races, excluding driver salaries and other expenses. Each chartered car now receives $12.5 million in annual revenue from NASCAR, up from $9 million during the last charter agreement. But that means teams have to make up the difference — $7.5 million per car, excluding driver salaries — through sponsorships.

The inability of 23XI Racing to consistently turn a profit is even more concerning when you consider that they have something no other team has: Michael Jordan.

Since joining NASCAR in 2021, 23XI Racing has leveraged Michael Jordan’s name, brand, and popularity to build one of the sport’s most impressive sponsorship portfolios. The team now generates $40 million annually from brands like Toyota, McDonald’s, Monster Energy, Xfinity, Columbia, Coca-Cola, and the Jordan Brand.

The ability to land sponsors is really the only thing keeping 23XI from losing money.

For example, if you compare 23XI Racing’s annual profit and loss statement to that of Front Row Motorsports, you’ll notice that Michael Jordan and Denny Hamlin’s team generates $30 million more in annual sponsorship revenue, with Front Row typically losing between $5 million and $10 million in a given year (excluding COVID). Add that up over 20 years, and Front Row says it has lost $100 million or more since 2005.

NASCAR’s response to these financials has always been that teams are spending too much and that if they want to consistently turn a profit, they need to cut expenses.

NASCAR’s lead attorney, Chris Yates from Latham & Watkins, has even explicitly called out Michael Jordan and Denny Hamlin during the trial for 1) building a brand new $35 million facility in Charlotte and then charging their own team $1 million in rent, and 2) spending $83,000 on a Christmas party for 23XI Racing employees in 2022.

I’ll let you decide whether those two expenses are egregious. However, the reality is that 23XI and Front Row aren’t the only teams struggling. According to a NASCAR-commissioned study that doesn’t include 23XI or Front Row due to litigation, as well as one other team, only 3 of NASCAR’s remaining 12 teams made a profit last year.

One NASCAR team finished the year with $3.08 million in profit, while the other two profitable teams brought in $130,951 and $143,890, respectively. As for the other nine teams that participated in the study, they collectively lost $33.4 million last year. If you add 23XI and Front Row’s losses to those numbers, at least 11 of NASCAR’s 15 teams lost money last year, with the average unprofitable team losing $4.1 million in 2024.

These financial losses have been a key argument for 23XI Racing and Front Row at trial. Jeffrey Kessler even read an email to the jury that Hendrick Motorsports owner Rick Hendrick sent to NASCAR CEO Jim France in 2024, stating that he had reached a “breaking point” and that, despite Hendrick Motorsports winning two NASCAR Cup Series championships over the past five seasons, the team still lost $20 million.

Of course, after proving that teams are struggling financially, 23XI and Front Row’s legal team was quick to point out that NASCAR generated more than $100 million in net income last year (not counting the profit they may have earned from their tracks).

NASCAR has been on its back foot for several months. Not only did Judge Kenneth Bell rule pretrial that NASCAR was a monopoly, but he also ruled that the relevant market was premier stock-car racing. That limited NASCAR’s ability to claim that teams could always race in other motorsports series, such as INDYCAR or Formula 1.

Antitrust cases are notoriously hard to predict. You just never know how a jury will respond. However, even the most neutral observer will tell you that the testimony and evidence presented over the last week and a half haven’t been good for NASCAR.

NASCAR executives have often said they don’t remember or can’t recall specific details. Michael Jordan has shown up to court every day as 23XI’s representative, a strategic move given his popularity. In fact, two jury members were dismissed for being Jordan fans, while another had to leave for saying, “NASCAR killed NASCAR.”

Judge Kenneth Bell warned both parties a year ago that they would be better off reaching a resolution before trial. While that might have sounded dramatic at the time, they should have listened to him. Now everyone’s dirty laundry is being aired out in public.

If NASCAR wins, 23XI Racing and Front Row Motorsports will likely shut down and leave the sport entirely. Having to go through this trial is bad enough. If the outcome leads to the country’s most popular athlete exiting NASCAR altogether, that’s worse.

However, if the jury finds that NASCAR has been using its monopoly power to limit race team finances and restrict competition, several other outcomes are possible.

Monetary damages could exceed $1 billion, as an economist testified during the trial that 23XI and Front Row are owed $364.7 million. The jury would decide if that is the correct number, but then a judge can triple the damages under U.S. antitrust law. If that happens, 23XI and Front Row would get paid but still likely leave NASCAR.

The judge would then determine how to break up NASCAR’s monopoly and limit anticompetitive practices. That could include forcing NASCAR to make charters permanent, share more revenue with teams, sell tracks, or dump exclusivity clauses.

But behind the scenes, many people seem to be rooting for a third option. Regardless of the trial’s outcome, NASCAR, 23XI Racing, and Front Row Motorsports can always negotiate a settlement before, during, or even after a verdict. Both parties will appeal if the trial doesn’t go their way, so there is still plenty of time to work out the details.

If you’re NASCAR, giving team owners some of what they want (permanent charters, voting rights, etc.) could end up saving you billions of dollars in the long run.

At this point though, it’s hard to see a clean ending for anyone. The evidence has exposed a business model that no longer works for most teams, and the longer this drags on, the more pressure NASCAR faces to rethink how the sport is structured.

Whether the jury rules for the teams or NASCAR eventually forces a negotiated peace, one thing is certain: this trial has already changed the sport by pulling back the curtain in a way that can’t be undone. And whatever comes next — a breakup, a settlement, or a complete redesign — will reshape stock-car racing for decades.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please share it with your friends.