Sports

The effects and post

Abstract

This study aimed to compare the effects of two high-intensity interval training modalities on body composition and muscular fitness in obese young adults and examined the characteristics of energy expenditure (EE) after training. Thirty-six obese young adults (eleven female, age: 22.1 ± 2.3 years, BMI: 25.1 ± 1.2 kg/m2) were to Whole-body high-intensity interval training group (WB-HIIT) (n = 12), jump rope high-intensity interval training group (JR-HIIT) (n = 12), or non-training control group (CG) (n = 12). WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups performed an 8-week HIIT protocol. WB-HIIT, according to the program of unarmed resistance training, JR-HIIT use rope-holding continuous jump training, each execution of 4 sets of 4 × 30 s training, interval 30 s, inter-set interval 1min, and the control group maintained their regular habits without additional exercise training. Body composition and muscular strength were assessed before and after 8 weeks. Repeated measures analysis of variance and clinical effect analysis using Cohen’s effect size were used, with a significance level of p < 0.05. In comparison with the CG group in both experimental groups, Body Mass and BMI significantly reduced (p < 0.05), and Muscular strength significantly improved (p < 0.05).WB-HIIT versus JR-HIIT: Fat Mass (− 1.5 ± 1.6; p = 0.02 vs − 2.3 ± 1.2; p < 0.01) and % Body Fat (− 1.3 ± 1.7; p = 0.05 vs − 1.9 ± 1.9; p < 0.01) the effect is more pronounced in the JR-HIIT group; Muscle Mass (1.5 ± 0.7; p < 0.01 vs − 0.8 ± 1.1; p = 0.07) the effect is more pronounced in the WB-HIIT group. Estimated daily energy intake (122 ± 459 vs 157 ± 313; p > 0.05). Compared to the CG, body composition was significantly improved in both intervention groups. All three groups had no significant changes in visceral adipose tissue (p > 0.05). Significant differences in Lipid and Carbohydrate oxidation and energy output were observed between the two groups, as well as substantial differences in WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT VO2, ventilation, and energy consumption minute during the 0–5 min post-exercise period (p > 0.05). WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT interventions effectively improve the body composition of young adults with obesity, while WB-HIIT additionally improves muscular fitness. After exercise, WB-HIIT produces higher excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and associated lipid and carbohydrate metabolism than JR-HIIT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

By 2022, 2.5 billion adults (43%) had excess body weight, of whom 890 million (16%) were obese. In 2019, excess body mass index was responsible for 5 million deaths from non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular and neurological diseases1. Obesity has become one of the global public health problems, and there is an association between physical activity and body weight in adults2. Physical activity is one of the most important ways of preventing and treating excessive weight and excess adiposity, and the World Health Organization recommends that adults engage in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week3. Despite the well-known benefits of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (PA), 31% of adults worldwide do not match the PA recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO)4. There are many barriers to adult participation in physical activity, such as environment, cost, equipment, and lack of time, and it is essential to provide adults with convenient, efficient, and easy-to-perform forms of exercise5.

Recently HIIT has received a lot of attention as an effective way to improve body composition, lipid metabolism6, and cardiorespiratory fitness in overweight and obese people7, and to improve exercise adherence8, a form of exercise that is safe, reliable, and well-tolerated9. However, classic HIIT modalities, including running, cycling, or rowing, still lack convenience for adults. These modalities could hurt exercise adherence, as “lack of enjoyment” is a commonly cited barrier to regular PA10. Whole-body HIIT (WB-HIIT) has recently received scholarly attention, WB-HIIT using weights as resistance can be an exciting and cost-effective alternative. It can help overcome exercise barriers such as lack of time, cost, limited facilities, and transportation difficulties11. WB-HIIT has the same effect as traditional high-intensity interval training, improving body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness, and more importantly, improving muscular endurance and strengthening skeletal muscle health12.

Schaun et al.13 demonstrated that 8 min of all-out style WB-HIIT (e.g., burpees, mountain climbers, squats, and jumping jacks) conducted 3 times per week for 16 weeks, elicited similar improvements in VO2max as MICT (30-min treadmill running, 3/week) in health men. Scoubeau et al.14 demonstrated that 8 weeks of home-based WB-HIIT elicited greater muscle endurance (~ 28%) improvement in inactive adults. Scott et al.15 demonstrated that 12 weeks of home-based WB-HIIT improve the structural and endothelial enzymatic properties of skeletal muscle in adults with obesity. Poon et al.16 demonstrated that WB-HIIT is relatively strenuous and triggers greater acute cardiometabolic stress than MICT compared to both MICT and ERG-HIIT training modalities. Jump ropes have been proposed to elevate PA and improve health in obese populations, requiring minimal, inexpensive equipment and limited space17. Additionally, several studies demonstrated that jump rope HIIT (JR-HIIT) can reduce inflammatory factors and improve body composition and cardiovascular health indicators in populations with obesity18,19.

Previous studies have shown that HIIT can effectively improve physical health, but the mechanism and effect of HIIT exercise after fat loss have not been clearly explained. Sturdy et al.20 research findings on kettlebell complexes and high-intensity functional training showed that there were no significant differences in EPOC produced after exercise, although significant associations were revealed for mean HR as well as post-exercise VE and Bla. Jiang et al.21 Demonstrate that HIIT post-exercise brings greater EPOC under isoenergetic constraints, especially in the first 10 min after exercise (HIIT:45.91 kcal and MICT: 34.39 kcal). Currently, controversial research exists on the effects of HIIT post-exercise on the production of EPOC in populations living with obesity. Different high-intensity interval training modalities have different effects on producing EPOC after exercise. Different forms of HIIT research are well worth exploring22. Both WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT are fast explosive exercises performed with their own weight, involving more muscle groups. We speculate that the reason why WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT improve body composition and achieve fat loss may be due to the mobilization of multi-joint training during exercise, which promotes the body’s energy expenditure.

WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT have been conducted more frequently in adolescents and healthy adults, but there is a lack of relevant studies on adults affected by obesity. Therefore, we will explore the effects of both WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT post-training on energy expenditure, body composition, and muscle fitness in adults with obesity.

Materials and methods

Participants and study design

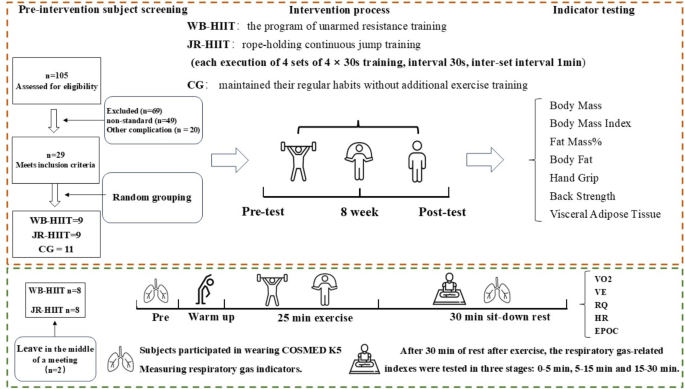

Thirty-six eligible young adults were recruited from a university, with the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged 18–30 years; (2) obesity determined by body mass index (BMI) > 24.0 kg/m223; (3) no regular PA or structured sports training within the last 6 months; (4) having a condition limiting participation to maximal physical test and training (e.g., cardiovascular or lung disease, neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorder). Following an explanation of the purpose and constraints of the study, all participants sign the written informed consent. This trial is registered on the Chinese clinical trial registry (ChiCTR2100048737; Date of registration:15 July 2021). The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the medical ethics committee of the Department of Medicine of Shenzhen University (PN-202400005; Date of registration:7 February 2024). This study was conducted between February and July of 2024. A flowchart and study design of this study is depicted in Fig. 1.

Participants Flowchart. Abbreviations: WB-HIIT, whole-body high-intensity interval training; JR-HIIT, jump rope high-intensity interval training; CG, no-training control.

Sample size

The sample size calculation using G*Power 3.1 (Version 3.1; Dusseldorf, Germany) was based on suggested previous findings of the adaptations in fat mass to HIIT (effect size of 0.45) in obese adults24. A two-tailed power calculation at an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.80 suggested that a minimum of 30 participants, 10 for each group, were required in this study. Given the ~ 20% dropout rate, the sample size was inflated to 12 participants per group.

Randomization and blinding

The randomly allocated sequence was a computer, SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA)-generated and sealed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. C.M. generated the random allocation sequence, Y.B.Q enrolled the participants, and Z.C.Q assigned the participants to interventions. This study is stratified by two age levels (18–24 years, 25–30 years), two genders (males and females), and two levels of BMI (24.0–25.0 kg/m2, > 25.0 kg/m2), with a total of 8 strata (2 × 2 × 2). As the participants were enrolled, we determined the stratum to which they belonged and were then separated and randomized to either WB-HIIT, JR-HIIT, or CG (after baseline testing, participants were assigned using the next envelope in the sequence). BIA and muscular fitness testers were blinded to group allocation.

Anthropometry and body composition

Participants were asked to fast 10 min before taking their anthropometry and body composition measurements, and to avoid strenuous physical training for 48 h. The standing height (in cm to the nearest 0.5 cm) was measured without shoes using a wall-mounted scale. Body mass (BM), body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage (%BF), Fat mass (FM), Muscle mass (MM), and estimated visceral adipose tissue area (VAT) were analyzed by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). BIA can be a reliable tool for measuring body composition and VAT; its reliability has been widely verified. The Inbody 770 Body Composition Monitor (Biospace Co., Seoul, Korea, 2021) was used to obtain foot-to-foot BIA measures per the manufacturer’s guidelines, with participants standing barefoot on the footplates. Before the measurement, all the participants entered their gender, age, and height (cm). Furthermore, to ensure measurement accuracy, each subject was measured three times, and the average was calculated (Table 1).

Assessment of muscular strength

Hand grip measurement procedure was adapted from the standardized procedure and script for muscular strength testing by Xu25. Grip strength was measured by an adjustable spring-loaded digital hand dynamometer (EH101, CAMRY, Guangdong, China) with a resolution of 0.1 kg. In each measurement, the Knob was adjusted to the appropriate position according to the size of the participant’s hand and squeezed the handle as hard as possible for approximately 3-s; three attempts were completed for a dominant hand with 30-s resting intervals between measurements. The researcher then recorded the highest measurement26.

The back strength test was conducted using the electronic back strength meter (BCS-400, HFD Tech Co., Beijing, China). The participant stood upright on the chassis of the back strength meter with both arms and hands straight and hanging down in front of the same side of the thigh so that the handle was in contact with the tips of the two fingers and the chain length was fixed at this height27. During the test, participants straightened both legs, tilted the upper body slightly forward, about 30 degrees, straightened both arms, held the handle tightly, palms inward, and pulled upward with maximum force. Test 2 times with 1-min rest interval, and record the maximum value, in kg.

Energy metabolism measurement

EPOC was measured using a portable gas metabolic analyzer COSMED k5 (K5, Italy). First, subjects’ quiet heart rate index tests were completed using Polar heart rate bands (Polar team pro, Polar, Kempele, Finland).

Gas exchange data were assessed for 30 min post-exercise while participants remained seated alone in a quiet room. This duration was selected as preliminary data showed that VO2 returned to baseline within 30 min post-exercise. Mean VO2, HR, and VE were determined as the average value from the entire 30 min post-exercise period; in addition, VO2, and VE were estimated at 5, 15, and 30 min by taking an average of the 5 (0–5 min), 10 (5–15 min), and 15 min (15–30) of data preceding each timepoint. Mean exercise intervention assessment results include the intervention period and 30 min after the end of the intervention, excluding the warm-up component.

We chose to collect 1 VO2 and VCO2 during each period of the intervention, and the total amount of VO2 and VCO2 over a fixed period was calculated by accumulating them and substituting them into the substrate metabolism equation28:

-

①

Carbohydrate oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) = 4.5850 VCO2 (ml/kg/min) − 3.2255 VO2 (ml/kg/min).

-

②

Lipid oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) = 1.6946 VO2 (ml/min/kg) − 1.7012 VCO2 (ml/kg/min).

-

③

Lipid energy output (cal/kg/min) = lipid oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) × 9;

-

④

Total energy output (cal/kg/min) = lipid oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) × 9 + carbohydrate oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) × 4;

-

⑤

Percentage of energy from lipid = Lipid energy output/Total energy output (%).

WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT protocol

WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT performed three sessions on non-consecutive days per week for 8 weeks. Before the training session, there is a 3-min warm-up and cool-down period. The WB-HIIT content was integrated by investigators based on a previous study14 and provided to participants through four videos created by our team. Participants performed 4 sets of exercises in one session including 4 × 30-s all-out whole-body exercises interspaced with 30-s of rest and 1-min rest between each set. Each exercise was proposed with a basic (1–2 set) and advanced variant (3–4) to promote progression, and the total duration of each session was about 25-min (Table 2). Participants in the JR-HIIT group performed 4 sets of jump rope in one session; each set included 4 × 30-s exercise interspaced with 30-s rest and 1-min rest between each set. Jump rope intensity at 100 jumps/min for 1–4 weeks progressed to 110 jumps/min for 5–6 weeks and 120 jumps/min for 7–8 weeks. The cadence of jumps was controlled by recording a rhythmic MP3. All JR-HIIT sessions were monitored by personal trainers who verified adherence to the training protocol. The selected JR-HIIT protocol refers to previous research in populations with obesity19. Heart rate (HR) during training was monitored by a heart rate belt (Polar team Oh1, Polar, Kemele, Finland) and recorded the average and maximal HR (HRmax) of each session and the time spent in different intensity zones, expressed in percentage of the estimated HRmax based on age (220—age): light (60–70%), moderate (70–80%), high (> 80% HRmax) intensity (Supplementary Table S1).

Dietary and exercise control

Daily energy intake was estimated with validated 24-h dietary recalls (3 weekdays and 1 weekend day) during the initial and the end of the training program. It was carried out by all participants with the help of their parents and/or the investigators. Energy intake based on the dietary records was calculated with commercial software (Boohee Health Software, Boohee Info Technology Co., Shanghai, China), averaged, and reported as kilocalories per day (kcal/day). Subjects were asked to maintain their current diet throughout the study.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistical Software Package (v20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Distributional assumptions were verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and non-parametric methods were utilized where appropriate. All data passed the normality and homogeneity tests. An ANOVA repeated measures test was used to compare the baseline data of the three groups and to compare changes in the different variables between groups. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures (3 groups: WB-HIIT vs. JR-HIIT vs. CG × 2 times: pre- vs. post-intervention). A post hoc test (with Bonferroni) was applied if the main factor was significant. Partial eta squared (η2) was used as effect size to measure the main and interaction effects, which was considered small when < 0.06 and large when > 0.1429. The within-group effect size was revealed by calculating Cohen’s d. Values of d = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 indicate small, medium, and large effect sizes30.

Results

Of the 105 subjects who entered the run-in phase, 36 were randomized. The other 69 participants were not randomized because of not meeting inclusion criteria (n = 24), having regular exercise (n = 17), having no time to participate (n = 8), and having other comorbidities (n = 20). During the 8-week intervention period, no adverse events were reported, but seven subjects were unable to complete the training program (Fig. 1). Specifically, three subjects reported that the training was not enjoyable (WB-HIIT = 1; JR-HIIT = 2); 2 reported they had no time to continue (WB-HIIT = 2); 1 had a personal reason to quit (JR-HIIT = 1); and 1 person not participant the post-test (CG = 1). Thus, 29 participants concluded the training program (WB-HIIT: 9; JR-HIIT: 9; CG: 11).

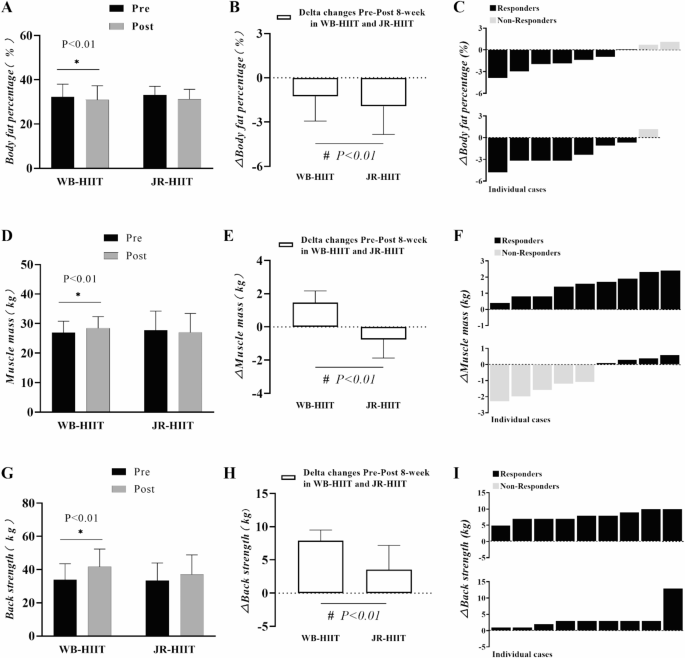

Following the training program, Body Mass (2.6%; p < 0.01), Body Mass Index (2.6%; p < 0.01), Fat Mass (6.8%; p = 0.02), and % Body Fat (3.9%; p = 0.05) decreased, while Muscle Mass (5.5%; p < 0.01), Hand Grip (8.8%; p < 0.01) and Back Strength (23.3%; p < 0.01) increased in the WB-HIIT group. Body Mass (4.0%; p < 0.01), Body Mass Index (4.2%; p < 0.01), Fat Mass (9.9%; p < 0.01), % Body Fat (5.8%; p < 0.01), Visceral Adipose Tissue (6.4%, p = 0.02) and Muscle Mass (2.7%; p = 0.07) decreased, while Hand Grip (6.3%, p < 0.01) and Back Strength (10.6%, p = 0.01) increased in the JR-HIIT group. Participants’ descriptive variables are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2.

Pre-post changes (A, D, G), delta (mean) (B, E, H), and delta (individual) (C, F, I) of body fat percentage, muscle mass, and back strength in obese young adults. * Denotes significant differences pre versus post within the group at level p < 0.01; # Denotes significant differences between WB-HIIT versus JR-HIIT at level p < 0.01.

Anthropometry and body composition

Table 3 presents data and statistical analysis of body composition at baseline and post-intervention. There were no differences in body mass (p = 0.758), BMI (p = 0.205), fat mass (p = 0.782), muscle mass (p = 0.700), hand grip (p = 0.339), and back strength (p = 0.502) at baseline in the three groups.

Following the 8-week intervention, the body mass (WB-HIIT = − 1.9 kg, 95% CI: − 2.1 to − 0.9, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 2.8 kg, 95% CI: − 3.9 to − 1.8, p < 0.05), BMI (WB-HIIT = − 0.7 kg/m2, 95% CI − 1.0 to − 0.3, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 1.0 kg/m2, 95% CI − 1.4 to − 0.7, p < 0.05), Fat mass (WB-HIIT = − 1.5 kg, 95% CI − 2.4 to − 0.7, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 2.3 kg, 95% CI − 3.2 to − 1.4, p < 0.05), and %body fat (WB-HIIT = − 1.3%, 95% CI − 2.3 to − 0.2, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 1.9%, 95% CI − 3.0 to − 0.9, p < 0.05) were reduced in all intervention groups. Muscle mass (1.5 kg, 95% CI 0.8–2.1, p < 0.05) had a significant increase in WB-HIIT, while a significant decrease (− 0.8 kg, 95% CI − 1.4 to − 0.1, p < 0.05) in JR-HIIT. In comparison to the CG, body composition had significantly improved in both intervention groups. All three groups had no significant changes in visceral adipose tissue (p > 0.05).

Muscular strength

The muscular strength of hand grip (WB-HIIT = 3.3 kg, 95% CI 2.4–4.2, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = 2.2 kg, 95% CI 1.4–3.3, p < 0.05), and back strength (WB-HIIT = 7.9 kg, 95% CI 5.0–8.4, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = 3.6 kg, 95% CI 2.2–5.6, p < 0.05) were increased in all three groups. When compared to JR-HIIT and CG, the back strength in WB-HIIT was significantly higher (p < 0.05).

EPOC after WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT

There were no significant differences in oxygen uptake between subjects at Base, during exercise, and at rest(p > 0.05), with total EPOC being significantly higher in the WB-HIIT(6.61 ± 2.12) than in the JR-HIIT (4.73 ± 0.92, p < 0.05); EPOC/BM WB-HIIT (88.69 ± 24.04, p < 0.05) was significantly higher than JR-HIIT (64.42 ± 10.01, p < 0.05) (Table 4).

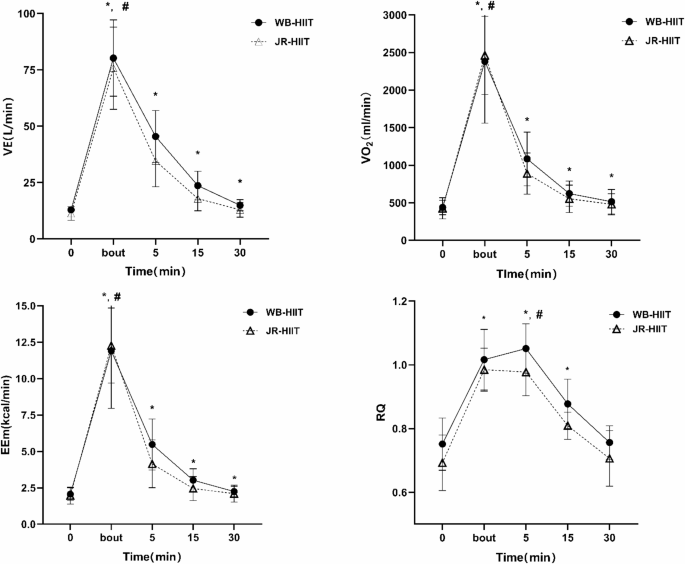

VO2 and RQ after WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT

Comparative analyses between the WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups showed significant differences in VO2 from 0 to 5 min after training (p < 0.05). Comparative studies between WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups showed substantial differences in RQ from 5 to 15 min after training (p < 0.05). Throughout the exercise intervention phases, significant differences were found in the within-group comparison analyses for the Train, 0-5min, and 5-15min phases when compared to baseline(p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

* Denotes significant differences pre versus post within the group at level p < 0.01; # Denotes significant differences between WB-HIIT versus JR-HIIT at level p < 0.01.

Ventilation and heart rate after

Comparative analyses between the WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups showed significant differences in VE from 0 to 5 min after training (p < 0.05). Throughout the exercise intervention phases, significant differences were found in the within-group comparison analyses for the Train, 0-5min, 5-15min, and 15-30min phases when compared to baseline (p < 0.05).

During training metabolic substrate

Analysis of glycolipid metabolism and energy output metrics in the two different groups during the intervention period revealed no significant differences in the rate of oxidation of glycolipids and energy output during the intervention period (Table 5).

After training metabolic substrate

Lipid oxidation rate was significantly higher in the WB-HIIT (2.04 ± 0.52) than in the JR-HIIT (0.95 ± 0.36, p < 0.05); lipid energy output was considerably higher in the WB-HIIT (18.32 ± 4.68) than in the JR-HIIT (8.53 ± 3.23. p < 0.05).

Carbohydrate oxidation rate was significantly higher in the JR-HIIT (7.17 ± 3.96) than in the WB-HIIT (12.13 ± 4.77, p < 0.05); The percentage of energy from lipid (%) was significantly higher in the WB-HIIT (0.4225 ± 0.15) than in the JR-HIIT (0.1588 ± 0.07, p < 0.05); There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of total energy expenditure (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the effects of two HIIT modalities on body composition and muscular strength in obese adults and compared the energy metabolism characteristics (e.g. VO2, EPOC, etc.) during and after training. Essentially, results showed that similar fat loss following WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT, and muscle mass increase in WB-HIIT was greater in comparison with JR-HIIT. Moreover, whole-body high-intensity interval training leads to further improvements in muscular strength after 8 weeks of exercise training.

Similar to our findings from Scott et al. obesity-affected adults who received 1-min work intermixed with 1-min rest WB-HIIT 3 times a week for 12 weeks, with HRmax ≥ 80%, significantly reduced body weight, BMI, and fat mass16. Another study further supports these conclusions that 20 weeks of WB-HIIT effectively improves the body composition of women impacted by obesity31. JR-HIIT seemed to have a better effect on reducing fat mass (− 9.9% vs.–6.6%). This finding is consistent with prior studies reporting decreases in body mass after jumping rope in obese adolescent populations19. Increased skeletal muscle mass (5.6%) is another benefit of WB-HIIT’s improved body composition. Muscle mass helps to increase basal metabolic rate and increase energy expenditure32. Another advantage of WB-HIIT compared with traditional HIIT is that it can increase skeletal muscle content and improve strength performance, which is consistent with the results of Scoubeau14. However, Van Baak et al. found that traditional functional and sprint HIIT forms have no significant impact on muscle endurance33. This difference may be due to differences in experimental design, particularly in terms of the level of supervision (supervised versus unsupervised environment) and training load parameters. Menz et al. adds resistance exercise to its training program to increase VO2max and muscle strength in overweight or obese adults34.

Obesity has been shown to decrease skeletal muscle through young and old adulthood35. Hand grip and back strength were commonly used for muscular fitness assessment26. Resistance training (RT) is a traditional mode that improves muscular strength, hypertrophy, and other muscle fitness. However, our results suggested that both WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT can effectively increase the hand grip, which reflected the improvement of total body strength and total body muscle mass. Moreover, WB-HIIT had a better effect on back strength increase (23.3%) with obesity adults, and in line with the increase of muscle mass (1.5 kg). Although the training load is moderate (i.e., body weight), WB-HIIT involves fast concentric and eccentric contractions by upper and lower limbs, combined with the high blood lactate concentration attained during WB-HIIT, which could have triggered the slight increase in muscle mass36,37,38,39,40. Higher training intensity increases the activation level of the nervous system and the recruitment efficiency of the neuromuscular, thereby strengthening muscle fiber contraction and improving muscular strength. In addition, the activation of the stretch-activated ion channel (SAC) and the increase in protein synthesis after WB-HIIT results in an increase the muscle size and activation of muscle fiber contraction41,42. These may be the potential mechanisms for WB-HIIT to enhance muscular strength.

In this study, we analyzed the potential mechanism of fat reduction effect of WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT from the perspective of energy metabolism. It has been pointed out that the difference in EPOC after exercise may be the reason why HIIT has a higher effect on fat reduction43,44. In this study, VO2, EPOC and RQ were measured during and after exercise in subjects using a gas metabolism analyzer (K5). Consistent with the Sturdy RE et al. study reports the HIFT 14 participants’ post-exercise responses demonstrated higher (0.91–6.67 L) EPOC20. The Haltom RW et al. study reported that performing two sets of 20 repetitions of 8 full-body workouts, with intensity and intervals similar to the WB-HIIT we used, triggered ~ 10 L of EPOC within 1 h of exercise, differing in that it was carried out in healthy males, and in the non-obese group45. Jiang et al. study reported that in obese men, HIIT (4343.17 ± 1723.03 ml) delivered much higher EPOC than isocaloric MICT (3049.78 ± 1217.93 ml) after exercise, with EPOC occurring predominantly in the 0–10 min period, which is similar to the present study’s results21.

A comparison of two different forms of high-intensity interval training, WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT, revealed that WB-HIIT produced higher EPOC than JR-HIIT, and higher lipid oxidation rate and energy output after exercise than JR-HIIT, especially at 0–5 min post-exercise, with significant differences between the VO2 and VE groups, which also demonstrated that resistance deadweight training could lead to more energy expenditure after exercise. Zouhal H showed that EPOC is higher after HIIT training by molecular mechanisms and that HIIT rapidly mobilizes fast-twitch muscle fibers and uncouples mitochondrial respiration, which increases pulmonary ventilation and catecholamine levels and consequently enhances EPOC46.

Potential mechanism of EPOC to promote fat loss, EPOC is affected by exercise intensity and duration47, WB-HIIT overcomes self-weighted exercise with high intensity and short intervals, which accelerates the time of stretching-shortening of the skeletal muscle, and thus enhances the body’s energy expenditure48, and at the same time induces an increase in post-exercise EPOC, which promotes fat burning49. Previous studies have shown that physical activity causes a significant increase in resting metabolism for up to 24 h after exercise, and the body’s ability to maintain energy expenditure beyond the original state level is referred to as EPOC50, which allows the body to consume more energy after a short period of activity. Greer BK et al. have shown that the body can consume more energy after a short period of activity by performing RT and HIIT training on females with a long-term background of aerobic exercise. RT and HIIT training stimulate an increase in EPOC51; Jung WS et al. normal obese women perform interval exercise at 80% VO2max higher than the energy expenditure after low-intensity exercise52. The high-intensity mixed neuromuscular training program (DoIT) has been demonstrated to effectively mitigate cardiometabolic health risks and reduce cardiovascular disease incidence in overweight/obesity women, while simultaneously enhancing musculoskeletal health indicators in this population53,54. In the current study, the two non-traditional HIIT modalities share fundamental similarities with DoIT, employing bodyweight resistance and incorporating specifically designed training protocols tailored to meet the physiological requirements of overweight/obese individuals, thereby facilitating the development of fundamental exercise patterns and promoting physiological adaptation. The implementation of simplified, accessible, and diversified training modalities offers an optimized exercise experience for overweight/obesity populations, thereby enhancing exercise adherence and long-term compliance.

HIIT training can improve long-term hippocampus function55. Post training provides metabolic benefits through systemic adaptations (e.g., cardiovascular remodeling, enhanced mitochondrial function), regulation of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) levels, and reduction of atherosclerosis risk, which may persist for a long time56,57. High compliance is the key to maintaining the effect. Studies have found that supervised group training can increase the compliance rate to more than 90%, which can better motivate subjects to actively participate in training. The combined application of HIIT and reasonable diet can produce additive effects, and giving more positive feedback to subjects is also a better maintenance strategy.

This study did not strictly control the participants’ dietary intake, which may have a potential impact on the EPOC measured by the participants. The study found that the thermal effect of the subjects’ food intake before the experiment can improve the VO2 of the body during the recovery period and affect the measurement of EPOC58. Carbohydrate and protein intake before exercise promotes enhanced glycogen synthesis and is beneficial to metabolism during exercise, thereby increasing EPOC production59. However, it was also found in other studies that under strict control of food intake, eating before exercise had no significant effect on EPOC60. Currently, the potential influence of diet on EPOC measurement may be influenced by food intake and individual differences. High proportion of fast muscle fibers is more likely to increase skeletal muscle content through training, while slow muscle fibers dominate the muscle building efficiency is lower61. The lack of dietary control is also a limitation of this study. The intensity of individual responses to testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) directly affects the rate of protein synthesis and thus muscle performance62. At the same time, due to the influence of program design, WB-HIIT can fully activate muscles and induce structural adaptation, while JR-HIIT has a high metabolic efficiency, but it is limited by the single action and mechanical stimulation intensity, which is difficult to match the specific needs of resistance training for muscle hypertrophy.

The present study verified the feasibility of two different exercise formats that required less space and equipment costs and were suitable for the majority of the population, and also compared the energy metabolism characteristics of the two formats during and after exercise, providing a valuable reference for subsequent related studies. Some limitations are worth discussing. The calorie consumption was not equalized in the training protocol. The subjects’ diet was not strictly controlled, and the thermic effect of food ingested before the experiment might have affected the measurements of the subjects’ EPOC. We used the BIA which has the advantages of portability and low cost, and its reliability has been widely confirmed, but the stability is lacking, and we will use dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to improve the accuracy in subsequent studies. Additionally, the sample size was relatively small, potentially increasing the variability of the results. In the future, it is necessary to expand the sample size and prolong the intervention time to determine the long-term effects and to explore the intervention effects of different forms of HIIT on overweight and obese populations from a more in-depth mechanistic point of view and different dose–response relationship studies.

Conclusions

Despite the very low training volume, WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT protocols performed three times per week improved body composition and muscular fitness after 8-week training and thus may serve as an interesting and time-efficient exercise strategy in young adults with obesity. Hence, whole-body exercise modality seems to affect the training responses regarding muscular strength, and this improvement was due to a greater increased muscle mass. More importantly, these results reinforce the benefits of HIIT regimes that employ body weight as a training load. The Whole-body high-intensity interval training compared to other traditional forms of exercise high-intensity interval training programs increases post-exercise EPOC and EE at the same exercise intensity. These whole-body or jump rope training protocols may be performed in a variety of different settings (e.g., schools, public parks, indoors, etc.) and do not require sophisticated equipment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight#%20. Accessed 2010. 14. 21.

-

Donnelly, J. E. et al. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41, 459–471 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

Jakicic, J. M. et al. Physical activity and the prevention of weight gain in adults: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 51, 1262–1269 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Bull, F. C. et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1451–1462 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Reichert, F. F., Barros, A. J., Domingues, M. R. & Hallal, P. C. The role of perceived personal barriers to engagement in leisure-time physical activity. Am. J. Public Health 97, 515–519 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Newsome, A. N. M. et al. ACSM worldwide fitness trends: Future directions of the health and fitness industry. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 28(11–25), 2024. https://doi.org/10.1249/fit.0000000000001017 (2025).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. Comparative efficacy of 5 exercise types on cardiometabolic health in overweight and obese adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of 81 randomized controlled trials. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 15, e008243. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.121.008243 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. & Fatouros, I. G. psychological adaptations to high-intensity interval training in overweight and obese adults: A topical review. Sports (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10050064 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Gremeaux, V. et al. Long-term lifestyle Intervention with optimized high-intensity interval training improves body composition, cardiometabolic risk, and exercise parameters in patients with abdominal obesity. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilit. 91, 941–950. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e3182643ce0 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Desai, M. N., Miller, W. C., Staples, B. & Bravender, T. Risk factors associated with overweight and obesity in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 57, 109–114 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Machado, A. F., Baker, J. S., Figueira Junior, A. J. & Bocalini, D. S. High-intensity interval training using whole-body exercises: Training recommendations and methodological overview. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 39, 378–383 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Broad, A. A., Howe, G. J., McKie, G. L., Vanderheyden, L. W. & Hazell, T. J. The effects of a pre-exercise meal on postexercise metabolism following a session of sprint interval training. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. = Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 45, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2019-0510 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Schaun, G. Z., Pinto, S. S., Silva, M. R., Dolinski, D. B. & Alberton, C. L. Whole-body high-intensity interval training induce similar cardiorespiratory adaptations compared with traditional high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training in healthy men. J. Strength Condition. Res. 32, 2730–2742 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Scoubeau, C., Carpentier, J., Baudry, S., Faoro, V. & Klass, M. Body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and neuromuscular adaptations induced by a home-based whole-body high intensity interval training. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 21, 226–236 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Scott, S. N. et al. Home-hit improves muscle capillarisation and eNOS/NAD(P)Hoxidase protein ratio in obese individuals with elevated cardiovascular disease risk. J. Physiol. 597, 4203–4225 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Poon, E. T., Chan, K. W., Wongpipit, W., Sun, F. & Wong, S. H. Acute physiological and perceptual responses to whole-body high-intensity interval training compared with equipment-based interval and continuous training. J. Sports Sci. Med. 22, 532–540 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Tomeleri, C. M. et al. Resistance training improves inflammatory level, lipid and glycemic profiles in obese older women: A randomized controlled trial. Exp. Gerontol. 84, 80–87 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Kim, E. S. et al. Improved insulin sensitivity and adiponectin level after exercise training in obese Korean youth. Obesity 15, 3023–3030 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Eskandari, M. et al. Effects of interval jump rope exercise combined with dark chocolate supplementation on inflammatory adipokine, cytokine concentrations, and body composition in obese adolescent boys. Nutrients 12, 3011 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Sturdy, R. E. & Astorino, T. A. Post-exercise metabolic response to kettlebell complexes versus high intensity functional training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-024-05579-z (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Jiang, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z. & Wang, Y. Acute interval running induces greater excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and lipid oxidation than isocaloric continuous running in men with obesity. Sci. Rep. 14, 9178 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Moniz, S. C., Islam, H. & Hazell, T. J. Mechanistic and methodological perspectives on the impact of intense interval training on post-exercise metabolism. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 30, 638–651 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Chen, C. & Lu, F. C. Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, P. R. C. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. Suppl. 17, 1–36 (2004).

-

Zhang, H. et al. Comparable effects of high-intensity interval training and prolonged continuous exercise training on abdominal visceral fat reduction in obese young women. J. Diab. Res. 2017, 5071740 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Xu, T. et al. Hand grip strength should be normalized by weight not height for eliminating the influence of individual differences: Findings from a cross-sectional study of 1511 healthy undergraduates. Front. Nutr. 9, 1063939 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Lockie, R. G. et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio in law enforcement agency recruits: Relationship to performance in physical fitness tests. J. Strength Condition. Res. 34, 1666–1675 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Zemkova, E., Poor, O. & Pecho, J. peak rate of force development and isometric maximum strength of back muscles are associated with power performance during load-lifting tasks. Am. J. Mens Health 13, 1557988319828622 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Sindorf, M. A. G. et al. Excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and substrate oxidation following high-intensity interval training: effects of recovery manipulation. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 14, 1151–1165 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Levine, T. R. & Hullett, C. R. Eta squared, partial eta squared, and misreporting of effect size in communication research. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 612–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00828.x (2002).

Google Scholar

-

Muller, K. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Technometrics 31, 499–500 (1989).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. High intensity, circuit-type integrated neuromuscular training alters energy balance and reduces body mass and fat in obese women: A 10-month training-detraining randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 13, e0202390 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Zurlo, F., Larson, K., Bogardus, C. & Ravussin, E. Skeletal muscle metabolism is a major determinant of resting energy expenditure. J. Clin. Invest. 86, 1423–1427 (1990).

Google Scholar

-

van Baak, M. A. et al. Effect of different types of regular exercise on physical fitness in adults with overweight or obesity: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Obes. Rev.: Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 22(Suppl 4), e13239. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13239 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Menz, V. et al. Functional versus running low-volume high-intensity interval training: Effects on VO(2)max and muscular endurance. J. Sports Sci. Med. 18, 497–504 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Maffiuletti, N. A. et al. Differences in quadriceps muscle strength and fatigue between lean and obese subjects. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 101, 51–59 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Duchateau, J., Stragier, S., Baudry, S. & Carpentier, A. Strength training. In search of optimal strategies to maximize neuromuscular performance. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 49, 2–14 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Arntz, F. et al. Effect of plyometric jump training on skeletal muscle hypertrophy in healthy individuals: A systematic review with multilevel meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 13, 888464 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Claflin, D. R. et al. Effects of high- and low-velocity resistance training on the contractile properties of skeletal muscle fibers from young and older humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(111), 1021–1030 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Carvalho, L. et al. Muscle hypertrophy and strength gains after resistance training with different volume-matched loads: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl. PhysiolNutr. Metab. 47, 357–368 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bellissimo, G. F. et al. The acute physiological and perceptual responses between bodyweight and treadmill running high-intensity interval exercises. Front. Physiol. 13, 824154 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Stary, C. M. & Hogan, M. C. Cytosolic calcium transients are a determinant of contraction-induced HSP72 transcription in single skeletal muscle fibers. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(120), 1260–1266 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Hansen, C. G., Ng, Y. L., Lam, W. L., Plouffe, S. W. & Guan, K. L. The Hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ promote cell growth by modulating amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Cell Res. 25, 1299–1313 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Børsheim, E. & Bahr, R. Effect of exercise intensity, duration and mode on post-exercise oxygen consumption. Sports Med. 33, 1037–1060 (2003).

Google Scholar

-

Hazell, T. J., Olver, T. D., Hamilton, C. D. & Lemon, P. W. R. Two minutes of sprint-interval exercise elicits 24-hr oxygen consumption similar to that of 30 min of continuous endurance exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 22, 276–283 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Haltom, R. W. et al. Circuit weight training and it s effects on excess postexercise oxygen consumption. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 31 (1999).

-

Zouhal, H., Jacob, C., Delamarche, P. & Gratas-Delamarche, A. Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender. Sports Med. 38, 401–423 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Scoubeau, C., Bonnechere, B., Cnop, M., Faoro, V. & Klass, M. Effectiveness of whole-body high-intensity interval training on health-related fitness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 9559 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Callahan, M. J., Parr, E. B., Hawley, J. A. & Camera, D. M. Can high-intensity interval training promote skeletal muscle anabolism?. Sports Med. 51, 405–421 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

LaForgia, J., Withers, R. & Gore, C. Effects of exercise intensity and duration on the excess post-exercise oxygen consumption. J. Sports Sci. 24, 1247–1264 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Gaesser, G. A. & Brooks, G. A. Metabolic bases of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption: A review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 16, 29–43 (1984).

Google Scholar

-

Greer, B. K., O’Brien, J., Hornbuckle, L. M. & Panton, L. B. EPOC comparison between resistance training and high-intensity interval training in aerobically fit women. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 14, 1027–1035 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Jung, W. S., Hwang, H., Kim, J., Park, H. Y. & Lim, K. Comparison of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption of different exercises in normal weight obesity women. J. Exerc. Nutrit. Biochem. 23, 22–27 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. Hybrid-type, multicomponent interval training upregulates musculoskeletal fitness of adults with overweight and obesity in a volume-dependent manner: A 1-year dose-response randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 23, 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.2025434 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. High-intensity interval neuromuscular training promotes exercise behavioral regulation, adherence and weight loss in inactive obese women. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 20, 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1663270 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Blackmore, D. G. et al. Long-term improvement in hippocampal-dependent learning ability in healthy, aged individuals following high intensity interval training. Aging Dis. https://doi.org/10.14336/ad.2024.0642 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Hawley, J. A., Hargreaves, M., Joyner, M. J. & Zierath, J. R. Integrative biology of exercise. Cell 159, 738–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.029 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Batacan, R. B. Jr., Duncan, M. J., Dalbo, V. J., Tucker, P. S. & Fenning, A. S. Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 51, 494–503. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095841 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Tsuji, K., Xu, Y., Liu, X. & Tabata, I. Effects of short-lasting supramaximal-intensity exercise on diet-induced increase in oxygen uptake. Physiol. Rep. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13506 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Ormsbee, M. J., Bach, C. W. & Baur, D. A. Pre-exercise nutrition: the role of macronutrients, modified starches and supplements on metabolism and endurance performance. Nutrients 6, 1782–1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6051782 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Broad, A. A., Howe, G. J., McKie, G. L., Vanderheyden, L. W. & Hazell, T. J. The effects of a pre-exercise meal on postexercise metabolism following a session of sprint interval training. Appl. Physiol. Nutrit. Metab. = Physiol. Appliquee Nutrit. Metab. 45, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2019-0510 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Aagaard, P. et al. A mechanism for increased contractile strength of human pennate muscle in response to strength training: Changes in muscle architecture. J. Physiol. 534, 613–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00613.x (2001).

Google Scholar

-

Van Every, D. W., D’Souza, A. C. & Phillips, S. M. Hormones, hypertrophy, and hype: An evidence-guided primer on endogenous endocrine influences on exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 52, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1249/jes.0000000000000346 (2024).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the School of Physical Education of Shenzhen University and the relevant participants for their support. This study was funded by the Science and Technology Innovation Project of the General Administration of Sport of China (ID: 22KICX035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YBQ:Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft. CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing–review and editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft. ZCQ: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. WXD: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

BaiQuan, Y., Meng, C., Congqing, Z. et al. The effects and post-exercise energy metabolism characteristics of different high-intensity interval training in obese adults.

Sci Rep 15, 13770 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98590-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Whole-body HIIT

- Jump rope HIIT

- Body composition

- Muscle fitness

- EPOC

- Obese adults

Sports

No. 3 Volleyball Opens NCAA Tournament Versus Campbell – Texas A&M Athletics

The Aggies ensured their third-straight tournament berth under the leadership of head coach Jamie Morrison, concluding the regular season and SEC Tournament with a 23-4 record. Their performance throughout the year earned them the highest AVCA ranking in program history of No. 6 and their first NCAA Tournament hosting opportunity since 2019.

Shining at home this season, the Maroon & White boast a 9-1 ledger at Reed Arena with its lone loss coming against then-No. 3 Kentucky (3-1). The 12th Man has been a force all year, as they helped break the program attendance record standing 9,801 strong versus Texas as well as accounting for another five top 10 attendances during the 2025 campaign.

Texas A&M’s depth of talent has been evident throughout the year and was rewarded during the SEC’s postseason honors, as a conference-high four Aggies were named to the All-SEC First Team including Logan Lednicky, Ifenna Cos-Okpalla, Maddie Waak and Kyndal Stowers. The honors didn’t stop there as Lednicky was named an AVCA Player of the Year Semifinalist, while the group accounted for 24 total accolades throughout the season.

The Matchups

Texas A&M enters its third NCAA Tournament with coach Morrison at the helm of the program, coming off a sweet 16 run during the 2024 season. The Maroon & White played the role of the hunter last season, downing No. 3 seed Arizona State in on their home court in the second round and came up just short in a five-set thriller against No. 2 seed Wisconsin.

The Aggies earned their highest seed since 2015 at No. 3 and welcome Campbell, TCU and SFA to Aggieland. They open their campaign versus the Camels who hold a 23-6 ledger and earned their second ever NCAA Tournament bid after winning the CAA Championship title in a five-set battle with Hofstra.

Friday’s meeting will be the first all-time between Texas A&M and Campbell. The Camels hold a strong 8-3 record when playing on the road but will come against the 12th Man and the Maroon & White’s 9-1 ledger in Reed Arena. On the stat sheet the Aggies hold the advantage in five of the seven team statical categories leading Campbell in kills per set, assists per set, hitting percentage, opponent hitting percentage and blocks per set, while the Camels have the upper hand in aces per set and digs per set.

Tracks and Trends

Logan Lednicky sits nine kills away from climbing to fourth in career kills at Texas A&M, she would pass three-time Olympian Stacy Sykora who has 1,586 kills.

Ifenna Cos-Okpalla has 159 blocks on the year and is three away from breaking her single season best of 161 and six from recording the most in a season since 1999 (165).

Streaming & Stats

Fans can watch the match on the ESPN+ and follow stats on 12thman.com.

Tickets

Fans can purchase their tickets to the opening round matches through 12thman.com/ncaatickets.

Students will be granted free admission to tomorrow’s game if they show their student ID’s at the north entry of Reed Arena.

Parking

Make plans to arrive early and exhibit patience for the expected traffic and parking congestion around Reed Arena. Multiple parking options are available for fans:

- General parking is available around the arena on gameday for $5 – cash AND card payments accepted.

- Fans with a valid TAMU parking pass can park for FREE in lots surrounding the arena. Make sure to have your pass barcode ready to show the lot attendant.

Follow the Aggies

Visit 12thMan.com for more information on Texas A&M volleyball. Fans can keep up to date with the A&M volleyball team on Facebook, Instagram and on Twitter by following @AggieVolleyball.

Sports

Volleyball Recaps – December 4

@#3 Wisconsin 3, Eastern Illinois 0

#3 WISCONSIN 3, EASTERN ILLINOIS 0

EIU dropped both sets one and two, struggling to find a rhythm early on. The Panthers trailed early in both of the first two sets right out of the gate and were unable to provide resistance. In set one, the Badgers hit 0.48% and 0.542% in set two. For the match, Wisconsin hit 0.435. EIU struggled connecting offensively, hitting 0% in set one and 0.022 overall. After the first two sets concluded, the Panthers looked for a spark, and Tori Mohesky answered the call with fireworks right from the jump. Mohesky earned a service ace to calm the Badgers crowd. EIU returned back-to-back points to hold their largest lead, fueled by Destiny Walker and a Wisconsin attack error. Shortly after, EIU trailed 15-9 heading into the media timeout. After the break in the action, both teams went back and forth trading points. Wisconsin reached set point 24-15. However, the Panthers found life and roared back into the match, scoring four straight unanswered points charged by a Katie Kopshever service ace and two blocks by Emma Schroeder and Sylvia Hasz. Unfortunately, the Badgers closed out the set 25-19.

By The Numbers: EIU records their third NCAA Tournament appearance in program history. Destiny Walker led the way offensively with 6 kills and 1 service ace. Sylvia Hasz collected 16 assists and 3 block assists. Defensively, Ariadne Pereles recorded 8 digs, while Emma Schroeder produced 5 block assists. Lilli Amettis and Katie Kopshever each collected a block assist.

The Panthers’ historic season comes to a close, finishing with a 24-8 (15-3 OVC) record. After being picked to finish 8th in the OVC preseason poll, EIU stormed through conference play, securing their second OVC title in three years. EIU also collected their fourth regular season title in the program’s history. The Panthers made their third NCAA Tournament appearance.

Sports

Women’s Volleyball Opens NCAA Tournament Against USF on Friday – Penn State

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa.- No. 25 Penn State opens its 45th-straight appearance in the NCAA Tournament with a first-round match against USF on Friday at Texas’s Gregory Gymnasium. The match is scheduled for 5:30 p.m. ET and will stream on ESPN+.

The winner of Friday’s match advances to play the winner between Texas and Florida A&M in the second round on Saturday.

HOW TO FOLLOW

Friday, Dec. 5 | 5:30 p.m. ET

No. 25 Penn State (18-12, 12-8 B1G) vs. USF (17-12, 12-4 AAC) | Live Stats | ESPN+

OPENING NOTES

• Penn State is set to open its 45th appearance in the NCAA Tournament. It is the only program in the country to play in all 45 NCAA Division I Women’s Volleyball Tournaments since the inaugural event in 1981.

• The Nittany Lions received an eight seed in the Austin Region and will play the first and second rounds away from Rec Hall for just the first time since the tournament was expenaded to 64 teams in 1998.

• Friday marks Penn State’s fourth NCAA Tournament appearance and 13th postseason match under Katie Schumacher-Cawley, who is in her fourth season as Penn State head coach. They are 10-2 in the NCAA Tournament under Schumacher-Cawley after going 6-0 and winning the program’s eighth national title last season.

• The Nittany Lions made it to at least the NCAA Regional Semifinal in each of Schumacher-Cawley’s first three seasons as head coach.

NCAA TOURNAMENT HISTORY

• Penn State, which has won eight national titles, including the most recent in 2024, is 116-35 all-time in the NCAA Tournament.

• Penn State has made the National Semifinals 14 times and the National Championship match 11 times.

• USF and Penn State will meet for the first time in the NCAA Tournament, making the Bulls the 76th different postseason opponent for the Nittany Lions. Just eight of those teams have a winning record against Penn State in the NCAA Tournament.

PENN STATE IN ROUND OF 64

• Penn State is 26-0 in the NCAA Tournament round of 64 since the event expanded to 64 teams in 1998.

• The Lions are 78-3 in sets played during that stretch, dropping one set to Howard in 2017, one to Towson in 2021, and one to Yale last season.

• Rec Hall was the venue for 24 of the 26 matches.

• Penn State is 3-0 in the Round of 64 under Schumacher-Cawley, beating UMBC in 2022, Yale in 2023, and Delaware State in 2024.

HOW THEY GOT HERE – PENN STATE

• Penn State earned an at-large bid to the NCAA Tournament after going 18-12 overall and 12-8 in the Big Ten.

• The Nittany Lions are one of 14 teams in the nation with four wins over teams ranked in the top 25 of RPI, beating No. 6 Creighton, No. 11 Wisconsin, No. 13 USC, and No. 15 Kansas.

• The Nittany Lions helped secure their spot in the NCAA Tournament with four wins in their final five matches, beating Ohio State (3-2), Michigan State (3-0), Maryland (3-0), and Iowa (3-1).

HOW THEY GOT HERE – USF

• USF received an at-large bid to the NCAA Tournament after going 17-12 overall and 12-4 in the American Conference on its way to a second-place finish in the conference standings. The Bulls lost to Tulsa in the semifinal round of the American Conference Tournament.

• The Bulls will play in the NCAA Tournament for the first time since 2002. They beat Florida State in the first round that year before falling to Florida in the second round.

• USF’s highest RPI win came in conference play with a sweep over No. 36 Tulsa. The highest non-conference RPI win came in five sets over No. 47 Dayton. They also pushed Purdue to five sets before losing in their season opener.

• Senior outside hitter Maria Clara Andrade was named the American Conference Player of the Year for the second-straight season. She was joined on the all-conference team by sophomore setter Raegan Richardson (first team) and junior outside hitter Laila Ivey (second team).

SERIES HISTORY – USF

• Penn State is 3-0 in the all-time series with USF. The teams first played in 1986.

• The Nittany Lions swept all three matches, winning 3-0 in 1986, 1988, and 2015. All three matches were played in Tampa.

• Penn State and USF have never met in the NCAA Tournament.

• Kennedy Martin is the only player on the Penn State roster that has played against USF. She hit .449 with 27 kills, six blocks, and two aces in Florida’s 3-2 win over the Bulls in 2023.

PENN STATE VS. AMERICAN CONFERENCE

• Penn State is 32-4 all-time against current members of American Conference.

• The Nittany Lions have played eight of the 13 teams in the conference and have a winning record against all eight. They are unbeaten against UAB (1-0), Charlotte (1-0), East Caroline (3-0), Memphis (2-0), Rice (3-0), South Florida (3-0), and Wichita State (1-0).

TOURNAMENT EXPERIENCE

• Eight Penn State players have combined for 50 matches of NCAA Tournament experience.

• Penn State head coach Katie Schumacher-Cawley (1999) and assistant coach Megan Hodge Easy (2007, 2008, 2009) combined for four national titles as players at Penn State.

Catherine Burke – 1 match

Ava Falduto – 6 matches

Gillian Grimes – 12 matches

Jordan Hopp – 6 matches (2 Iowa State, 4 Penn State)

Caroline Jurevicius – 6 matches

Kennedy Martin – 5 matches (5 Florida)

Maggie Mendelson – 8 matches (2 Nebraska, 6 Penn State)

Jocelyn Nathan – 6 matches

The 2025 Penn State women’s volleyball season is presented by Musselman’s.

Sports

Toledo Falls in First Round of NCAA Tournament to Indiana, 3-0

The Rockets finish the season with a 23-11 record, posting the second-most wins in program history .(1983 – 27 matches)

Sophomore Olivia Heitkamp led the Toledo offense with 11 kills, including five in the first set, for her 19th match this season in double-figures. Redshirt junior Sophie Catalano poured in seven terminations while redshirt sophomore Sierra Pertzborn chipped in six kills of her own.

Senior setter Kelsey Smith tallied 26 assists and a team-high nine digs. Sophomore Grace Freiberger and senior Macy Medors each totaled six digs.

Quoting Head Coach Brian Wright

“We’ve had a pretty special season in the past 11-and-a-half months that I’ve been at Toledo. I am so proud of this team and how they played tonight’s match. This team accomplished many great things this season, from leading the MAC in attendance, to winning their first MAC Tournament championship and playing in their first NCAA Tournament match. I want the team to understand that they are enough and capable to compete with the best teams and programs in this country.”

Senior Anna Alford

(on the 2025 season)

“This group has made Toledo history and it’s been such a great season. We’ve been working so hard for the past 11-and-a-half months and we just wanted a chance to showcase our abilities on the court and the love that this team has for one another.”

Senior Macy Medors

(on the future of the Toledo volleyball program)

“Our program is built on being a family and there is a great atmosphere amongst everyone involved. The younger players will continue that tradition and help Toledo volleyball continue to grow to new heights.”

Key Moments

- Olivia Heitkamp started the match with a kill as the Rockets and Hoosiers traded points early in the first set. Heitkamp’s fifth kill of the set kept it even, 11-11, before two quick points from Indiana gave the Hoosiers a 15-12 lead at the media timeout. A block from Anna Alford and Heitkamp kept UT within four, 22-18, but a quick 3-0 run for the Hoosiers gave them the set win.

- Both sides went back-and-forth to begin the second set before Indiana jumped out to a 7-4 lead. A solo block from Jessica Costlow sent the Rockets on a 3-0 run to even the frame, 9-9. The Hoosiers responded with an 8-2 run of their own to take a seven-point advantage, 19-12. Kills from Heitkamp and Sophie Catalano put UT within five, 19-14, but Indiana took the set win with four-straight points.

- Catalano fired off a kill to give Toledo a lead in the third set, 4-3. A quick 3-0 surge by the Rockets, highlighted by a kill from Sierra Pertzborn and Catalano, kept Toledo ahead, 7-5. Two service aces and two kills from the Hoosiers put IU in front, 12-9, before Heitkamp and Catalano each buried terminations to even the frame, 13-13. Indiana went on a 3-0 run to retake the lead, 17-14. Catalano and Pertzborn combined for a second block to stay within three, 19-16, but the Hoosiers ended the match on a 6-1 run to take the win.

Follow the Rockets

Instagram: Toledo_VB

Twitter/X: Toledo_VB

Facebook: Toledo Volleyball

Sports

Volleyball sweeps Fairmont State in first round of Atlantic Regionals

ERIE, Pa. – Indiana (PA) swept Fairmont St. 25-22, 25-19, 25-20 on Thursday at Highmark Events Center in Erie, Pa., in a neutral non-conference matchup.

Indiana (PA) was led by Charlotte Potvin, who posted 13 kills on a team-high .455 hitting percentage, adding four aces and 17.5 points in the three-set win. Delaney Concannon contributed 16 kills with 22 digs, while setter Ellie Rauch dished 45 assists and recorded two service aces.

Jessica Neiman added 14 kills on .464 hitting, while libero Lexi McLanahan finished with 15 digs. Rylee Brown anchored the front row with one solo block and two block assists, totaling three blocks and 2.0 points.

Indiana (PA) hit .268 for the match with 49 kills and 59 digs.

Fairmont St. saw 33 kills from a balanced attack and 49 digs defensively. Outside hitter Joey Borelle recorded 13 kills and seven digs, while Josie Nobbe totaled 11 digs and four kills. Chloe McDaniel added eight kills and four block assists.

The match featured 14 ties and nine lead changes in the opening set before Indiana pulled away late, scoring two straight points from the service line to close it out.

Indiana (PA) improved to 21-8 on the season, while Fairmont St. fell to 23-11.

Sports

Kentucky volleyball tops Wofford in Lexington NCAA tournament bracket

Updated Dec. 4, 2025, 11:27 p.m. ET

- Top-seeded Kentucky volleyball defeated Wofford in three sets to advance in the NCAA Tournament.

- Brooklyn DeLeye led Kentucky with 14 kills during the first-round victory.

- Kentucky will now face No. 8 seed UCLA for a spot in the Sweet 16.

LEXINGTON — Top-seeded Kentucky volleyball defeated Wofford in three sets Thursday night at Historic Memorial Coliseum to advance to the second round of the NCAA Tournament.

Brooklyn DeLeye led the Wildcats with 14 kills.

“This team especially, our depth, is so strong, and I think that just helps in practice,” DeLeye said after the match. “We’re pushing one another. No spot is guaranteed, and I think that’s truly helped us get to this No. 1 seed.”

UK will battle No. 8 seed UCLA Friday at 7 p.m. for a spot in the Sweet 16. UCLA defeated Georgia Tech in five sets Thursday night. A familiar face in former Louisville and current UCLA middle blocker Phekran Kong will sit across the net.

The ability to play in their home gym is huge for the Wildcats, coach Craig Skinner said.

“There’s a lot of really good teams, and every night out you got to be ready. You got to be ready for an enormous amount of challenges. And for us to be able to do that on our home floor is significant, and definitely we aren’t going to take that for granted.”

Kentucky takes a 23-match win streak into the second round after going undefeated in SEC play en route to the No. 2 overall seed. UK won the 2020 national championship, the first in program history.

Coverage during the match:

The Wildcats recorded 66 digs in three sets against the Terriers, led by junior libero Molly Tuozzo (19).

“I think it just all comes down to scouting and preparation,” Tuozzo said after the match. “I think we watched their hitters a lot beforehand, so we knew kind of their hard shots and what they like to do.”

UK completes its 15th sweep of 2025, besting Wofford in three sets (25-11, 25-19, 25-12). The Wildcats will face the No. 8 seed UCLA Bruins tomorrow night at Historic Memorial Coliseum. First serve is scheduled for 7 p.m.

UK is moments away from advancing to the second round of the NCAA Tournament. Brooklyn DeLeye leads all players with 13.5 points and 12 kills.

The Wildcats are one set away from their 15th sweep of the season and advancing to the second round of the NCAA Tournament. UK ended that frame on a 5-0 scoring run. Brooklyn DeLeye leads all players with nine kills.

The Wildcats regain the lead, marking the fourth time advantage has changed hands in this set. There have been 13 ties.

The Terriers lead with 11 kills.

UK takes the first set in a true team effort. Eva Hudson led the Wildcats with five kills, but five different Kentucky players notched at least one in the opening frame: Brooklyn DeLeye and Lizzie Carr have three each; Brooke Bultema has two; and Asia Thigpen has one. Kentucky ended the first set on a 4-0 scoring run.

The Wildcats lead early. Four UK players have kills already: Brooklyn DeLeye (2), Eva Hudson (2), Brooke Bultema (1) and Lizzie Carr (1).

Tonight’s match between No. 1 seed Kentucky and Wofford will begin 30 minutes after the conclusion of a 4:30 p.m. first-round match between Georgia Tech and No. 8 seed UCLA at Historic Memorial Coliseum.

Buy Kentucky volleyball tickets here

The match between the Wildcats and the Terriers will not air on a traditional TV channel.

It’ll be on ESPN+, which is available exclusively via livestream. Click here to subscribe.

UK will play No. 8 seed UCLA at 7 p.m. Friday. Here’s a look at the tournament schedule:

- First and second rounds: Dec. 4-6

- Regionals: Dec. 11-14

- Semifinals: Dec. 18 at T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Missouri

- Championship: Dec. 21 at T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Missouri

Click here to view the complete bracket.

- Aug. 23: Kentucky 4, Ohio State 0 (exhibition)

- Aug. 30: Kentucky 3, Lipscomb 0

- Aug. 31: Nebraska 3, Kentucky 2

- Sept. 5: Kentucky 3, Penn State 0

- Sept. 6: Kentucky 3, New Hampshire 0

- Sept. 10: Pitt 3, Kentucky 0

- Sept. 13: Kentucky 3, SMU 1

- Sept. 14: Kentucky 3, Houston 0

- Sept. 18: Kentucky 3, Louisville 2

- Sept. 20: Kentucky 3, Washington 0

- Sept. 24: Kentucky 3, South Carolina 0

- Sept. 26: Kentucky 3, Georgia 0

- Oct. 3: Kentucky 3, Ole Miss 0

- Oct. 8: Kentucky 3, Texas A&M 1

- Oct. 12: Kentucky 3, LSU 0

- Oct, 15: Kentucky 3, Auburn 0

- Oct. 19: Kentucky 3, Florida 2

- Oct. 24: Kentucky 3, Mississippi State 1

- Oct. 26: Kentucky 3, Alabama 0

- Oct. 31: Kentucky 3, Vanderbilt 0

- Nov. 2: Kentucky 3, Texas 0

- Nov. 6: Kentucky 3, Missouri 1

- Nov. 9: Kentucky 3, Tennessee 1

- Nov. 14: Kentucky 3, Oklahoma 2

- Nov. 16: Kentucky 3, Arkansas 0

- Nov. 23: Kentucky 3, Auburn 0 (SEC Tournament Quarterfinals)

- Nov. 24: Kentucky 3, Tennessee 1 (SEC Tournament Semifinals)

- Nov. 25: Kentucky 3, Texas 2 (SEC Tournament Final)

- Dec. 4: Kentucky 3, Wofford 0 (NCAA Tournament First Round)

- Dec. 5: Kentucky vs. UCLA (NCAA Tournament Second Round)

Reach college sports enterprise reporter Payton Titus at ptitus@gannett.com and follow her on X @petitus25. Subscribe to her “Full-court Press” newsletterhere for a behind-the-scenes look at how college sports’ biggest stories are impacting Louisville and Kentucky athletics.

-

Rec Sports2 weeks ago

Rec Sports2 weeks agoFirst Tee Winter Registration is open

-

Rec Sports1 week ago

Rec Sports1 week agoFargo girl, 13, dies after collapsing during school basketball game – Grand Forks Herald

-

Motorsports1 week ago

Motorsports1 week agoCPG Brands Like Allegra Are Betting on F1 for the First Time

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks agoVolleyball Recaps – November 18

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoF1 Las Vegas: Verstappen win, Norris and Piastri DQ tighten 2025 title fight

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoTwo Pro Volleyball Leagues Serve Up Plans for Minnesota Teams

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoUtah State Announces 2025-26 Indoor Track & Field Schedule

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoSycamores unveil 2026 track and field schedule

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoTexas volleyball vs Kentucky game score: Live SEC tournament updates

-

NIL5 days ago

NIL5 days agoBowl Projections: ESPN predicts 12-team College Football Playoff bracket, full bowl slate after Week 14