Sports

The effects and post

Abstract

This study aimed to compare the effects of two high-intensity interval training modalities on body composition and muscular fitness in obese young adults and examined the characteristics of energy expenditure (EE) after training. Thirty-six obese young adults (eleven female, age: 22.1 ± 2.3 years, BMI: 25.1 ± 1.2 kg/m2) were to Whole-body high-intensity interval training group (WB-HIIT) (n = 12), jump rope high-intensity interval training group (JR-HIIT) (n = 12), or non-training control group (CG) (n = 12). WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups performed an 8-week HIIT protocol. WB-HIIT, according to the program of unarmed resistance training, JR-HIIT use rope-holding continuous jump training, each execution of 4 sets of 4 × 30 s training, interval 30 s, inter-set interval 1min, and the control group maintained their regular habits without additional exercise training. Body composition and muscular strength were assessed before and after 8 weeks. Repeated measures analysis of variance and clinical effect analysis using Cohen’s effect size were used, with a significance level of p < 0.05. In comparison with the CG group in both experimental groups, Body Mass and BMI significantly reduced (p < 0.05), and Muscular strength significantly improved (p < 0.05).WB-HIIT versus JR-HIIT: Fat Mass (− 1.5 ± 1.6; p = 0.02 vs − 2.3 ± 1.2; p < 0.01) and % Body Fat (− 1.3 ± 1.7; p = 0.05 vs − 1.9 ± 1.9; p < 0.01) the effect is more pronounced in the JR-HIIT group; Muscle Mass (1.5 ± 0.7; p < 0.01 vs − 0.8 ± 1.1; p = 0.07) the effect is more pronounced in the WB-HIIT group. Estimated daily energy intake (122 ± 459 vs 157 ± 313; p > 0.05). Compared to the CG, body composition was significantly improved in both intervention groups. All three groups had no significant changes in visceral adipose tissue (p > 0.05). Significant differences in Lipid and Carbohydrate oxidation and energy output were observed between the two groups, as well as substantial differences in WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT VO2, ventilation, and energy consumption minute during the 0–5 min post-exercise period (p > 0.05). WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT interventions effectively improve the body composition of young adults with obesity, while WB-HIIT additionally improves muscular fitness. After exercise, WB-HIIT produces higher excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and associated lipid and carbohydrate metabolism than JR-HIIT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

By 2022, 2.5 billion adults (43%) had excess body weight, of whom 890 million (16%) were obese. In 2019, excess body mass index was responsible for 5 million deaths from non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular and neurological diseases1. Obesity has become one of the global public health problems, and there is an association between physical activity and body weight in adults2. Physical activity is one of the most important ways of preventing and treating excessive weight and excess adiposity, and the World Health Organization recommends that adults engage in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week3. Despite the well-known benefits of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (PA), 31% of adults worldwide do not match the PA recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO)4. There are many barriers to adult participation in physical activity, such as environment, cost, equipment, and lack of time, and it is essential to provide adults with convenient, efficient, and easy-to-perform forms of exercise5.

Recently HIIT has received a lot of attention as an effective way to improve body composition, lipid metabolism6, and cardiorespiratory fitness in overweight and obese people7, and to improve exercise adherence8, a form of exercise that is safe, reliable, and well-tolerated9. However, classic HIIT modalities, including running, cycling, or rowing, still lack convenience for adults. These modalities could hurt exercise adherence, as “lack of enjoyment” is a commonly cited barrier to regular PA10. Whole-body HIIT (WB-HIIT) has recently received scholarly attention, WB-HIIT using weights as resistance can be an exciting and cost-effective alternative. It can help overcome exercise barriers such as lack of time, cost, limited facilities, and transportation difficulties11. WB-HIIT has the same effect as traditional high-intensity interval training, improving body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness, and more importantly, improving muscular endurance and strengthening skeletal muscle health12.

Schaun et al.13 demonstrated that 8 min of all-out style WB-HIIT (e.g., burpees, mountain climbers, squats, and jumping jacks) conducted 3 times per week for 16 weeks, elicited similar improvements in VO2max as MICT (30-min treadmill running, 3/week) in health men. Scoubeau et al.14 demonstrated that 8 weeks of home-based WB-HIIT elicited greater muscle endurance (~ 28%) improvement in inactive adults. Scott et al.15 demonstrated that 12 weeks of home-based WB-HIIT improve the structural and endothelial enzymatic properties of skeletal muscle in adults with obesity. Poon et al.16 demonstrated that WB-HIIT is relatively strenuous and triggers greater acute cardiometabolic stress than MICT compared to both MICT and ERG-HIIT training modalities. Jump ropes have been proposed to elevate PA and improve health in obese populations, requiring minimal, inexpensive equipment and limited space17. Additionally, several studies demonstrated that jump rope HIIT (JR-HIIT) can reduce inflammatory factors and improve body composition and cardiovascular health indicators in populations with obesity18,19.

Previous studies have shown that HIIT can effectively improve physical health, but the mechanism and effect of HIIT exercise after fat loss have not been clearly explained. Sturdy et al.20 research findings on kettlebell complexes and high-intensity functional training showed that there were no significant differences in EPOC produced after exercise, although significant associations were revealed for mean HR as well as post-exercise VE and Bla. Jiang et al.21 Demonstrate that HIIT post-exercise brings greater EPOC under isoenergetic constraints, especially in the first 10 min after exercise (HIIT:45.91 kcal and MICT: 34.39 kcal). Currently, controversial research exists on the effects of HIIT post-exercise on the production of EPOC in populations living with obesity. Different high-intensity interval training modalities have different effects on producing EPOC after exercise. Different forms of HIIT research are well worth exploring22. Both WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT are fast explosive exercises performed with their own weight, involving more muscle groups. We speculate that the reason why WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT improve body composition and achieve fat loss may be due to the mobilization of multi-joint training during exercise, which promotes the body’s energy expenditure.

WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT have been conducted more frequently in adolescents and healthy adults, but there is a lack of relevant studies on adults affected by obesity. Therefore, we will explore the effects of both WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT post-training on energy expenditure, body composition, and muscle fitness in adults with obesity.

Materials and methods

Participants and study design

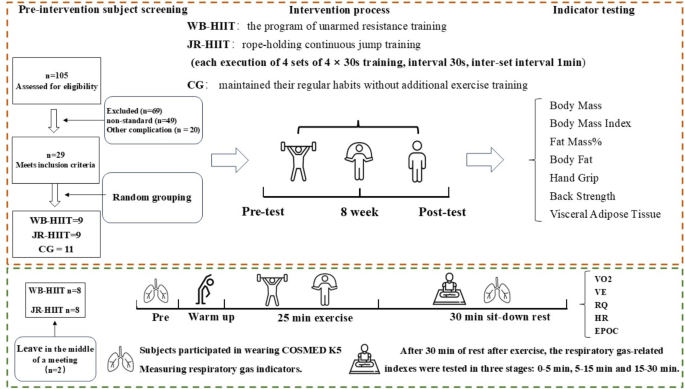

Thirty-six eligible young adults were recruited from a university, with the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged 18–30 years; (2) obesity determined by body mass index (BMI) > 24.0 kg/m223; (3) no regular PA or structured sports training within the last 6 months; (4) having a condition limiting participation to maximal physical test and training (e.g., cardiovascular or lung disease, neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorder). Following an explanation of the purpose and constraints of the study, all participants sign the written informed consent. This trial is registered on the Chinese clinical trial registry (ChiCTR2100048737; Date of registration:15 July 2021). The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the medical ethics committee of the Department of Medicine of Shenzhen University (PN-202400005; Date of registration:7 February 2024). This study was conducted between February and July of 2024. A flowchart and study design of this study is depicted in Fig. 1.

Participants Flowchart. Abbreviations: WB-HIIT, whole-body high-intensity interval training; JR-HIIT, jump rope high-intensity interval training; CG, no-training control.

Sample size

The sample size calculation using G*Power 3.1 (Version 3.1; Dusseldorf, Germany) was based on suggested previous findings of the adaptations in fat mass to HIIT (effect size of 0.45) in obese adults24. A two-tailed power calculation at an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.80 suggested that a minimum of 30 participants, 10 for each group, were required in this study. Given the ~ 20% dropout rate, the sample size was inflated to 12 participants per group.

Randomization and blinding

The randomly allocated sequence was a computer, SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA)-generated and sealed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. C.M. generated the random allocation sequence, Y.B.Q enrolled the participants, and Z.C.Q assigned the participants to interventions. This study is stratified by two age levels (18–24 years, 25–30 years), two genders (males and females), and two levels of BMI (24.0–25.0 kg/m2, > 25.0 kg/m2), with a total of 8 strata (2 × 2 × 2). As the participants were enrolled, we determined the stratum to which they belonged and were then separated and randomized to either WB-HIIT, JR-HIIT, or CG (after baseline testing, participants were assigned using the next envelope in the sequence). BIA and muscular fitness testers were blinded to group allocation.

Anthropometry and body composition

Participants were asked to fast 10 min before taking their anthropometry and body composition measurements, and to avoid strenuous physical training for 48 h. The standing height (in cm to the nearest 0.5 cm) was measured without shoes using a wall-mounted scale. Body mass (BM), body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage (%BF), Fat mass (FM), Muscle mass (MM), and estimated visceral adipose tissue area (VAT) were analyzed by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). BIA can be a reliable tool for measuring body composition and VAT; its reliability has been widely verified. The Inbody 770 Body Composition Monitor (Biospace Co., Seoul, Korea, 2021) was used to obtain foot-to-foot BIA measures per the manufacturer’s guidelines, with participants standing barefoot on the footplates. Before the measurement, all the participants entered their gender, age, and height (cm). Furthermore, to ensure measurement accuracy, each subject was measured three times, and the average was calculated (Table 1).

Assessment of muscular strength

Hand grip measurement procedure was adapted from the standardized procedure and script for muscular strength testing by Xu25. Grip strength was measured by an adjustable spring-loaded digital hand dynamometer (EH101, CAMRY, Guangdong, China) with a resolution of 0.1 kg. In each measurement, the Knob was adjusted to the appropriate position according to the size of the participant’s hand and squeezed the handle as hard as possible for approximately 3-s; three attempts were completed for a dominant hand with 30-s resting intervals between measurements. The researcher then recorded the highest measurement26.

The back strength test was conducted using the electronic back strength meter (BCS-400, HFD Tech Co., Beijing, China). The participant stood upright on the chassis of the back strength meter with both arms and hands straight and hanging down in front of the same side of the thigh so that the handle was in contact with the tips of the two fingers and the chain length was fixed at this height27. During the test, participants straightened both legs, tilted the upper body slightly forward, about 30 degrees, straightened both arms, held the handle tightly, palms inward, and pulled upward with maximum force. Test 2 times with 1-min rest interval, and record the maximum value, in kg.

Energy metabolism measurement

EPOC was measured using a portable gas metabolic analyzer COSMED k5 (K5, Italy). First, subjects’ quiet heart rate index tests were completed using Polar heart rate bands (Polar team pro, Polar, Kempele, Finland).

Gas exchange data were assessed for 30 min post-exercise while participants remained seated alone in a quiet room. This duration was selected as preliminary data showed that VO2 returned to baseline within 30 min post-exercise. Mean VO2, HR, and VE were determined as the average value from the entire 30 min post-exercise period; in addition, VO2, and VE were estimated at 5, 15, and 30 min by taking an average of the 5 (0–5 min), 10 (5–15 min), and 15 min (15–30) of data preceding each timepoint. Mean exercise intervention assessment results include the intervention period and 30 min after the end of the intervention, excluding the warm-up component.

We chose to collect 1 VO2 and VCO2 during each period of the intervention, and the total amount of VO2 and VCO2 over a fixed period was calculated by accumulating them and substituting them into the substrate metabolism equation28:

-

①

Carbohydrate oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) = 4.5850 VCO2 (ml/kg/min) − 3.2255 VO2 (ml/kg/min).

-

②

Lipid oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) = 1.6946 VO2 (ml/min/kg) − 1.7012 VCO2 (ml/kg/min).

-

③

Lipid energy output (cal/kg/min) = lipid oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) × 9;

-

④

Total energy output (cal/kg/min) = lipid oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) × 9 + carbohydrate oxidation rate (mg/kg/min) × 4;

-

⑤

Percentage of energy from lipid = Lipid energy output/Total energy output (%).

WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT protocol

WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT performed three sessions on non-consecutive days per week for 8 weeks. Before the training session, there is a 3-min warm-up and cool-down period. The WB-HIIT content was integrated by investigators based on a previous study14 and provided to participants through four videos created by our team. Participants performed 4 sets of exercises in one session including 4 × 30-s all-out whole-body exercises interspaced with 30-s of rest and 1-min rest between each set. Each exercise was proposed with a basic (1–2 set) and advanced variant (3–4) to promote progression, and the total duration of each session was about 25-min (Table 2). Participants in the JR-HIIT group performed 4 sets of jump rope in one session; each set included 4 × 30-s exercise interspaced with 30-s rest and 1-min rest between each set. Jump rope intensity at 100 jumps/min for 1–4 weeks progressed to 110 jumps/min for 5–6 weeks and 120 jumps/min for 7–8 weeks. The cadence of jumps was controlled by recording a rhythmic MP3. All JR-HIIT sessions were monitored by personal trainers who verified adherence to the training protocol. The selected JR-HIIT protocol refers to previous research in populations with obesity19. Heart rate (HR) during training was monitored by a heart rate belt (Polar team Oh1, Polar, Kemele, Finland) and recorded the average and maximal HR (HRmax) of each session and the time spent in different intensity zones, expressed in percentage of the estimated HRmax based on age (220—age): light (60–70%), moderate (70–80%), high (> 80% HRmax) intensity (Supplementary Table S1).

Dietary and exercise control

Daily energy intake was estimated with validated 24-h dietary recalls (3 weekdays and 1 weekend day) during the initial and the end of the training program. It was carried out by all participants with the help of their parents and/or the investigators. Energy intake based on the dietary records was calculated with commercial software (Boohee Health Software, Boohee Info Technology Co., Shanghai, China), averaged, and reported as kilocalories per day (kcal/day). Subjects were asked to maintain their current diet throughout the study.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistical Software Package (v20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Distributional assumptions were verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and non-parametric methods were utilized where appropriate. All data passed the normality and homogeneity tests. An ANOVA repeated measures test was used to compare the baseline data of the three groups and to compare changes in the different variables between groups. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures (3 groups: WB-HIIT vs. JR-HIIT vs. CG × 2 times: pre- vs. post-intervention). A post hoc test (with Bonferroni) was applied if the main factor was significant. Partial eta squared (η2) was used as effect size to measure the main and interaction effects, which was considered small when < 0.06 and large when > 0.1429. The within-group effect size was revealed by calculating Cohen’s d. Values of d = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 indicate small, medium, and large effect sizes30.

Results

Of the 105 subjects who entered the run-in phase, 36 were randomized. The other 69 participants were not randomized because of not meeting inclusion criteria (n = 24), having regular exercise (n = 17), having no time to participate (n = 8), and having other comorbidities (n = 20). During the 8-week intervention period, no adverse events were reported, but seven subjects were unable to complete the training program (Fig. 1). Specifically, three subjects reported that the training was not enjoyable (WB-HIIT = 1; JR-HIIT = 2); 2 reported they had no time to continue (WB-HIIT = 2); 1 had a personal reason to quit (JR-HIIT = 1); and 1 person not participant the post-test (CG = 1). Thus, 29 participants concluded the training program (WB-HIIT: 9; JR-HIIT: 9; CG: 11).

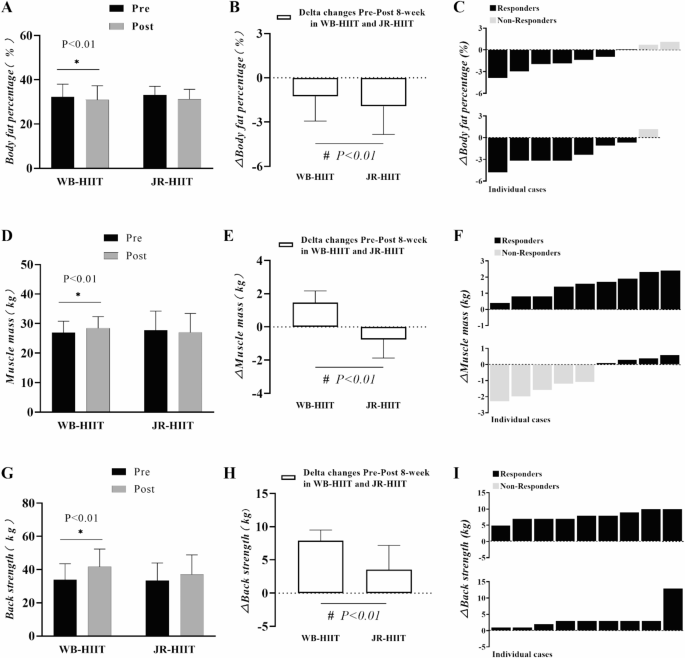

Following the training program, Body Mass (2.6%; p < 0.01), Body Mass Index (2.6%; p < 0.01), Fat Mass (6.8%; p = 0.02), and % Body Fat (3.9%; p = 0.05) decreased, while Muscle Mass (5.5%; p < 0.01), Hand Grip (8.8%; p < 0.01) and Back Strength (23.3%; p < 0.01) increased in the WB-HIIT group. Body Mass (4.0%; p < 0.01), Body Mass Index (4.2%; p < 0.01), Fat Mass (9.9%; p < 0.01), % Body Fat (5.8%; p < 0.01), Visceral Adipose Tissue (6.4%, p = 0.02) and Muscle Mass (2.7%; p = 0.07) decreased, while Hand Grip (6.3%, p < 0.01) and Back Strength (10.6%, p = 0.01) increased in the JR-HIIT group. Participants’ descriptive variables are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2.

Pre-post changes (A, D, G), delta (mean) (B, E, H), and delta (individual) (C, F, I) of body fat percentage, muscle mass, and back strength in obese young adults. * Denotes significant differences pre versus post within the group at level p < 0.01; # Denotes significant differences between WB-HIIT versus JR-HIIT at level p < 0.01.

Anthropometry and body composition

Table 3 presents data and statistical analysis of body composition at baseline and post-intervention. There were no differences in body mass (p = 0.758), BMI (p = 0.205), fat mass (p = 0.782), muscle mass (p = 0.700), hand grip (p = 0.339), and back strength (p = 0.502) at baseline in the three groups.

Following the 8-week intervention, the body mass (WB-HIIT = − 1.9 kg, 95% CI: − 2.1 to − 0.9, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 2.8 kg, 95% CI: − 3.9 to − 1.8, p < 0.05), BMI (WB-HIIT = − 0.7 kg/m2, 95% CI − 1.0 to − 0.3, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 1.0 kg/m2, 95% CI − 1.4 to − 0.7, p < 0.05), Fat mass (WB-HIIT = − 1.5 kg, 95% CI − 2.4 to − 0.7, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 2.3 kg, 95% CI − 3.2 to − 1.4, p < 0.05), and %body fat (WB-HIIT = − 1.3%, 95% CI − 2.3 to − 0.2, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = − 1.9%, 95% CI − 3.0 to − 0.9, p < 0.05) were reduced in all intervention groups. Muscle mass (1.5 kg, 95% CI 0.8–2.1, p < 0.05) had a significant increase in WB-HIIT, while a significant decrease (− 0.8 kg, 95% CI − 1.4 to − 0.1, p < 0.05) in JR-HIIT. In comparison to the CG, body composition had significantly improved in both intervention groups. All three groups had no significant changes in visceral adipose tissue (p > 0.05).

Muscular strength

The muscular strength of hand grip (WB-HIIT = 3.3 kg, 95% CI 2.4–4.2, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = 2.2 kg, 95% CI 1.4–3.3, p < 0.05), and back strength (WB-HIIT = 7.9 kg, 95% CI 5.0–8.4, p < 0.05; JR-HIIT = 3.6 kg, 95% CI 2.2–5.6, p < 0.05) were increased in all three groups. When compared to JR-HIIT and CG, the back strength in WB-HIIT was significantly higher (p < 0.05).

EPOC after WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT

There were no significant differences in oxygen uptake between subjects at Base, during exercise, and at rest(p > 0.05), with total EPOC being significantly higher in the WB-HIIT(6.61 ± 2.12) than in the JR-HIIT (4.73 ± 0.92, p < 0.05); EPOC/BM WB-HIIT (88.69 ± 24.04, p < 0.05) was significantly higher than JR-HIIT (64.42 ± 10.01, p < 0.05) (Table 4).

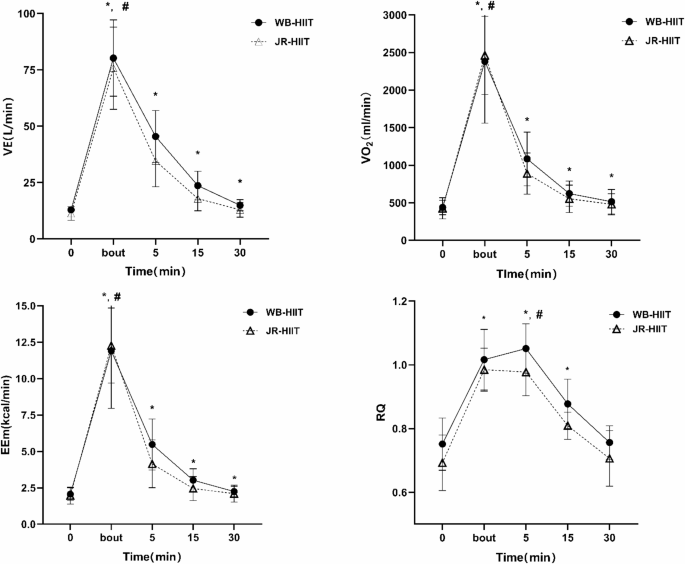

VO2 and RQ after WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT

Comparative analyses between the WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups showed significant differences in VO2 from 0 to 5 min after training (p < 0.05). Comparative studies between WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups showed substantial differences in RQ from 5 to 15 min after training (p < 0.05). Throughout the exercise intervention phases, significant differences were found in the within-group comparison analyses for the Train, 0-5min, and 5-15min phases when compared to baseline(p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

* Denotes significant differences pre versus post within the group at level p < 0.01; # Denotes significant differences between WB-HIIT versus JR-HIIT at level p < 0.01.

Ventilation and heart rate after

Comparative analyses between the WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT groups showed significant differences in VE from 0 to 5 min after training (p < 0.05). Throughout the exercise intervention phases, significant differences were found in the within-group comparison analyses for the Train, 0-5min, 5-15min, and 15-30min phases when compared to baseline (p < 0.05).

During training metabolic substrate

Analysis of glycolipid metabolism and energy output metrics in the two different groups during the intervention period revealed no significant differences in the rate of oxidation of glycolipids and energy output during the intervention period (Table 5).

After training metabolic substrate

Lipid oxidation rate was significantly higher in the WB-HIIT (2.04 ± 0.52) than in the JR-HIIT (0.95 ± 0.36, p < 0.05); lipid energy output was considerably higher in the WB-HIIT (18.32 ± 4.68) than in the JR-HIIT (8.53 ± 3.23. p < 0.05).

Carbohydrate oxidation rate was significantly higher in the JR-HIIT (7.17 ± 3.96) than in the WB-HIIT (12.13 ± 4.77, p < 0.05); The percentage of energy from lipid (%) was significantly higher in the WB-HIIT (0.4225 ± 0.15) than in the JR-HIIT (0.1588 ± 0.07, p < 0.05); There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of total energy expenditure (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the effects of two HIIT modalities on body composition and muscular strength in obese adults and compared the energy metabolism characteristics (e.g. VO2, EPOC, etc.) during and after training. Essentially, results showed that similar fat loss following WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT, and muscle mass increase in WB-HIIT was greater in comparison with JR-HIIT. Moreover, whole-body high-intensity interval training leads to further improvements in muscular strength after 8 weeks of exercise training.

Similar to our findings from Scott et al. obesity-affected adults who received 1-min work intermixed with 1-min rest WB-HIIT 3 times a week for 12 weeks, with HRmax ≥ 80%, significantly reduced body weight, BMI, and fat mass16. Another study further supports these conclusions that 20 weeks of WB-HIIT effectively improves the body composition of women impacted by obesity31. JR-HIIT seemed to have a better effect on reducing fat mass (− 9.9% vs.–6.6%). This finding is consistent with prior studies reporting decreases in body mass after jumping rope in obese adolescent populations19. Increased skeletal muscle mass (5.6%) is another benefit of WB-HIIT’s improved body composition. Muscle mass helps to increase basal metabolic rate and increase energy expenditure32. Another advantage of WB-HIIT compared with traditional HIIT is that it can increase skeletal muscle content and improve strength performance, which is consistent with the results of Scoubeau14. However, Van Baak et al. found that traditional functional and sprint HIIT forms have no significant impact on muscle endurance33. This difference may be due to differences in experimental design, particularly in terms of the level of supervision (supervised versus unsupervised environment) and training load parameters. Menz et al. adds resistance exercise to its training program to increase VO2max and muscle strength in overweight or obese adults34.

Obesity has been shown to decrease skeletal muscle through young and old adulthood35. Hand grip and back strength were commonly used for muscular fitness assessment26. Resistance training (RT) is a traditional mode that improves muscular strength, hypertrophy, and other muscle fitness. However, our results suggested that both WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT can effectively increase the hand grip, which reflected the improvement of total body strength and total body muscle mass. Moreover, WB-HIIT had a better effect on back strength increase (23.3%) with obesity adults, and in line with the increase of muscle mass (1.5 kg). Although the training load is moderate (i.e., body weight), WB-HIIT involves fast concentric and eccentric contractions by upper and lower limbs, combined with the high blood lactate concentration attained during WB-HIIT, which could have triggered the slight increase in muscle mass36,37,38,39,40. Higher training intensity increases the activation level of the nervous system and the recruitment efficiency of the neuromuscular, thereby strengthening muscle fiber contraction and improving muscular strength. In addition, the activation of the stretch-activated ion channel (SAC) and the increase in protein synthesis after WB-HIIT results in an increase the muscle size and activation of muscle fiber contraction41,42. These may be the potential mechanisms for WB-HIIT to enhance muscular strength.

In this study, we analyzed the potential mechanism of fat reduction effect of WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT from the perspective of energy metabolism. It has been pointed out that the difference in EPOC after exercise may be the reason why HIIT has a higher effect on fat reduction43,44. In this study, VO2, EPOC and RQ were measured during and after exercise in subjects using a gas metabolism analyzer (K5). Consistent with the Sturdy RE et al. study reports the HIFT 14 participants’ post-exercise responses demonstrated higher (0.91–6.67 L) EPOC20. The Haltom RW et al. study reported that performing two sets of 20 repetitions of 8 full-body workouts, with intensity and intervals similar to the WB-HIIT we used, triggered ~ 10 L of EPOC within 1 h of exercise, differing in that it was carried out in healthy males, and in the non-obese group45. Jiang et al. study reported that in obese men, HIIT (4343.17 ± 1723.03 ml) delivered much higher EPOC than isocaloric MICT (3049.78 ± 1217.93 ml) after exercise, with EPOC occurring predominantly in the 0–10 min period, which is similar to the present study’s results21.

A comparison of two different forms of high-intensity interval training, WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT, revealed that WB-HIIT produced higher EPOC than JR-HIIT, and higher lipid oxidation rate and energy output after exercise than JR-HIIT, especially at 0–5 min post-exercise, with significant differences between the VO2 and VE groups, which also demonstrated that resistance deadweight training could lead to more energy expenditure after exercise. Zouhal H showed that EPOC is higher after HIIT training by molecular mechanisms and that HIIT rapidly mobilizes fast-twitch muscle fibers and uncouples mitochondrial respiration, which increases pulmonary ventilation and catecholamine levels and consequently enhances EPOC46.

Potential mechanism of EPOC to promote fat loss, EPOC is affected by exercise intensity and duration47, WB-HIIT overcomes self-weighted exercise with high intensity and short intervals, which accelerates the time of stretching-shortening of the skeletal muscle, and thus enhances the body’s energy expenditure48, and at the same time induces an increase in post-exercise EPOC, which promotes fat burning49. Previous studies have shown that physical activity causes a significant increase in resting metabolism for up to 24 h after exercise, and the body’s ability to maintain energy expenditure beyond the original state level is referred to as EPOC50, which allows the body to consume more energy after a short period of activity. Greer BK et al. have shown that the body can consume more energy after a short period of activity by performing RT and HIIT training on females with a long-term background of aerobic exercise. RT and HIIT training stimulate an increase in EPOC51; Jung WS et al. normal obese women perform interval exercise at 80% VO2max higher than the energy expenditure after low-intensity exercise52. The high-intensity mixed neuromuscular training program (DoIT) has been demonstrated to effectively mitigate cardiometabolic health risks and reduce cardiovascular disease incidence in overweight/obesity women, while simultaneously enhancing musculoskeletal health indicators in this population53,54. In the current study, the two non-traditional HIIT modalities share fundamental similarities with DoIT, employing bodyweight resistance and incorporating specifically designed training protocols tailored to meet the physiological requirements of overweight/obese individuals, thereby facilitating the development of fundamental exercise patterns and promoting physiological adaptation. The implementation of simplified, accessible, and diversified training modalities offers an optimized exercise experience for overweight/obesity populations, thereby enhancing exercise adherence and long-term compliance.

HIIT training can improve long-term hippocampus function55. Post training provides metabolic benefits through systemic adaptations (e.g., cardiovascular remodeling, enhanced mitochondrial function), regulation of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) levels, and reduction of atherosclerosis risk, which may persist for a long time56,57. High compliance is the key to maintaining the effect. Studies have found that supervised group training can increase the compliance rate to more than 90%, which can better motivate subjects to actively participate in training. The combined application of HIIT and reasonable diet can produce additive effects, and giving more positive feedback to subjects is also a better maintenance strategy.

This study did not strictly control the participants’ dietary intake, which may have a potential impact on the EPOC measured by the participants. The study found that the thermal effect of the subjects’ food intake before the experiment can improve the VO2 of the body during the recovery period and affect the measurement of EPOC58. Carbohydrate and protein intake before exercise promotes enhanced glycogen synthesis and is beneficial to metabolism during exercise, thereby increasing EPOC production59. However, it was also found in other studies that under strict control of food intake, eating before exercise had no significant effect on EPOC60. Currently, the potential influence of diet on EPOC measurement may be influenced by food intake and individual differences. High proportion of fast muscle fibers is more likely to increase skeletal muscle content through training, while slow muscle fibers dominate the muscle building efficiency is lower61. The lack of dietary control is also a limitation of this study. The intensity of individual responses to testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) directly affects the rate of protein synthesis and thus muscle performance62. At the same time, due to the influence of program design, WB-HIIT can fully activate muscles and induce structural adaptation, while JR-HIIT has a high metabolic efficiency, but it is limited by the single action and mechanical stimulation intensity, which is difficult to match the specific needs of resistance training for muscle hypertrophy.

The present study verified the feasibility of two different exercise formats that required less space and equipment costs and were suitable for the majority of the population, and also compared the energy metabolism characteristics of the two formats during and after exercise, providing a valuable reference for subsequent related studies. Some limitations are worth discussing. The calorie consumption was not equalized in the training protocol. The subjects’ diet was not strictly controlled, and the thermic effect of food ingested before the experiment might have affected the measurements of the subjects’ EPOC. We used the BIA which has the advantages of portability and low cost, and its reliability has been widely confirmed, but the stability is lacking, and we will use dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to improve the accuracy in subsequent studies. Additionally, the sample size was relatively small, potentially increasing the variability of the results. In the future, it is necessary to expand the sample size and prolong the intervention time to determine the long-term effects and to explore the intervention effects of different forms of HIIT on overweight and obese populations from a more in-depth mechanistic point of view and different dose–response relationship studies.

Conclusions

Despite the very low training volume, WB-HIIT and JR-HIIT protocols performed three times per week improved body composition and muscular fitness after 8-week training and thus may serve as an interesting and time-efficient exercise strategy in young adults with obesity. Hence, whole-body exercise modality seems to affect the training responses regarding muscular strength, and this improvement was due to a greater increased muscle mass. More importantly, these results reinforce the benefits of HIIT regimes that employ body weight as a training load. The Whole-body high-intensity interval training compared to other traditional forms of exercise high-intensity interval training programs increases post-exercise EPOC and EE at the same exercise intensity. These whole-body or jump rope training protocols may be performed in a variety of different settings (e.g., schools, public parks, indoors, etc.) and do not require sophisticated equipment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight#%20. Accessed 2010. 14. 21.

-

Donnelly, J. E. et al. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41, 459–471 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

Jakicic, J. M. et al. Physical activity and the prevention of weight gain in adults: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 51, 1262–1269 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Bull, F. C. et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1451–1462 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Reichert, F. F., Barros, A. J., Domingues, M. R. & Hallal, P. C. The role of perceived personal barriers to engagement in leisure-time physical activity. Am. J. Public Health 97, 515–519 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Newsome, A. N. M. et al. ACSM worldwide fitness trends: Future directions of the health and fitness industry. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 28(11–25), 2024. https://doi.org/10.1249/fit.0000000000001017 (2025).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. Comparative efficacy of 5 exercise types on cardiometabolic health in overweight and obese adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of 81 randomized controlled trials. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 15, e008243. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.121.008243 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. & Fatouros, I. G. psychological adaptations to high-intensity interval training in overweight and obese adults: A topical review. Sports (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10050064 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Gremeaux, V. et al. Long-term lifestyle Intervention with optimized high-intensity interval training improves body composition, cardiometabolic risk, and exercise parameters in patients with abdominal obesity. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilit. 91, 941–950. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e3182643ce0 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Desai, M. N., Miller, W. C., Staples, B. & Bravender, T. Risk factors associated with overweight and obesity in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 57, 109–114 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Machado, A. F., Baker, J. S., Figueira Junior, A. J. & Bocalini, D. S. High-intensity interval training using whole-body exercises: Training recommendations and methodological overview. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 39, 378–383 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Broad, A. A., Howe, G. J., McKie, G. L., Vanderheyden, L. W. & Hazell, T. J. The effects of a pre-exercise meal on postexercise metabolism following a session of sprint interval training. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. = Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 45, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2019-0510 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Schaun, G. Z., Pinto, S. S., Silva, M. R., Dolinski, D. B. & Alberton, C. L. Whole-body high-intensity interval training induce similar cardiorespiratory adaptations compared with traditional high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training in healthy men. J. Strength Condition. Res. 32, 2730–2742 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Scoubeau, C., Carpentier, J., Baudry, S., Faoro, V. & Klass, M. Body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and neuromuscular adaptations induced by a home-based whole-body high intensity interval training. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 21, 226–236 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Scott, S. N. et al. Home-hit improves muscle capillarisation and eNOS/NAD(P)Hoxidase protein ratio in obese individuals with elevated cardiovascular disease risk. J. Physiol. 597, 4203–4225 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Poon, E. T., Chan, K. W., Wongpipit, W., Sun, F. & Wong, S. H. Acute physiological and perceptual responses to whole-body high-intensity interval training compared with equipment-based interval and continuous training. J. Sports Sci. Med. 22, 532–540 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Tomeleri, C. M. et al. Resistance training improves inflammatory level, lipid and glycemic profiles in obese older women: A randomized controlled trial. Exp. Gerontol. 84, 80–87 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Kim, E. S. et al. Improved insulin sensitivity and adiponectin level after exercise training in obese Korean youth. Obesity 15, 3023–3030 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Eskandari, M. et al. Effects of interval jump rope exercise combined with dark chocolate supplementation on inflammatory adipokine, cytokine concentrations, and body composition in obese adolescent boys. Nutrients 12, 3011 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Sturdy, R. E. & Astorino, T. A. Post-exercise metabolic response to kettlebell complexes versus high intensity functional training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-024-05579-z (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Jiang, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z. & Wang, Y. Acute interval running induces greater excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and lipid oxidation than isocaloric continuous running in men with obesity. Sci. Rep. 14, 9178 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Moniz, S. C., Islam, H. & Hazell, T. J. Mechanistic and methodological perspectives on the impact of intense interval training on post-exercise metabolism. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 30, 638–651 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Chen, C. & Lu, F. C. Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, P. R. C. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. Suppl. 17, 1–36 (2004).

-

Zhang, H. et al. Comparable effects of high-intensity interval training and prolonged continuous exercise training on abdominal visceral fat reduction in obese young women. J. Diab. Res. 2017, 5071740 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Xu, T. et al. Hand grip strength should be normalized by weight not height for eliminating the influence of individual differences: Findings from a cross-sectional study of 1511 healthy undergraduates. Front. Nutr. 9, 1063939 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Lockie, R. G. et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio in law enforcement agency recruits: Relationship to performance in physical fitness tests. J. Strength Condition. Res. 34, 1666–1675 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Zemkova, E., Poor, O. & Pecho, J. peak rate of force development and isometric maximum strength of back muscles are associated with power performance during load-lifting tasks. Am. J. Mens Health 13, 1557988319828622 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Sindorf, M. A. G. et al. Excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and substrate oxidation following high-intensity interval training: effects of recovery manipulation. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 14, 1151–1165 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Levine, T. R. & Hullett, C. R. Eta squared, partial eta squared, and misreporting of effect size in communication research. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 612–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00828.x (2002).

Google Scholar

-

Muller, K. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Technometrics 31, 499–500 (1989).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. High intensity, circuit-type integrated neuromuscular training alters energy balance and reduces body mass and fat in obese women: A 10-month training-detraining randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 13, e0202390 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Zurlo, F., Larson, K., Bogardus, C. & Ravussin, E. Skeletal muscle metabolism is a major determinant of resting energy expenditure. J. Clin. Invest. 86, 1423–1427 (1990).

Google Scholar

-

van Baak, M. A. et al. Effect of different types of regular exercise on physical fitness in adults with overweight or obesity: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Obes. Rev.: Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 22(Suppl 4), e13239. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13239 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Menz, V. et al. Functional versus running low-volume high-intensity interval training: Effects on VO(2)max and muscular endurance. J. Sports Sci. Med. 18, 497–504 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Maffiuletti, N. A. et al. Differences in quadriceps muscle strength and fatigue between lean and obese subjects. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 101, 51–59 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Duchateau, J., Stragier, S., Baudry, S. & Carpentier, A. Strength training. In search of optimal strategies to maximize neuromuscular performance. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 49, 2–14 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Arntz, F. et al. Effect of plyometric jump training on skeletal muscle hypertrophy in healthy individuals: A systematic review with multilevel meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 13, 888464 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Claflin, D. R. et al. Effects of high- and low-velocity resistance training on the contractile properties of skeletal muscle fibers from young and older humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(111), 1021–1030 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Carvalho, L. et al. Muscle hypertrophy and strength gains after resistance training with different volume-matched loads: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl. PhysiolNutr. Metab. 47, 357–368 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bellissimo, G. F. et al. The acute physiological and perceptual responses between bodyweight and treadmill running high-intensity interval exercises. Front. Physiol. 13, 824154 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Stary, C. M. & Hogan, M. C. Cytosolic calcium transients are a determinant of contraction-induced HSP72 transcription in single skeletal muscle fibers. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(120), 1260–1266 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Hansen, C. G., Ng, Y. L., Lam, W. L., Plouffe, S. W. & Guan, K. L. The Hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ promote cell growth by modulating amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Cell Res. 25, 1299–1313 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Børsheim, E. & Bahr, R. Effect of exercise intensity, duration and mode on post-exercise oxygen consumption. Sports Med. 33, 1037–1060 (2003).

Google Scholar

-

Hazell, T. J., Olver, T. D., Hamilton, C. D. & Lemon, P. W. R. Two minutes of sprint-interval exercise elicits 24-hr oxygen consumption similar to that of 30 min of continuous endurance exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 22, 276–283 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Haltom, R. W. et al. Circuit weight training and it s effects on excess postexercise oxygen consumption. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 31 (1999).

-

Zouhal, H., Jacob, C., Delamarche, P. & Gratas-Delamarche, A. Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender. Sports Med. 38, 401–423 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Scoubeau, C., Bonnechere, B., Cnop, M., Faoro, V. & Klass, M. Effectiveness of whole-body high-intensity interval training on health-related fitness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 9559 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Callahan, M. J., Parr, E. B., Hawley, J. A. & Camera, D. M. Can high-intensity interval training promote skeletal muscle anabolism?. Sports Med. 51, 405–421 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

LaForgia, J., Withers, R. & Gore, C. Effects of exercise intensity and duration on the excess post-exercise oxygen consumption. J. Sports Sci. 24, 1247–1264 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Gaesser, G. A. & Brooks, G. A. Metabolic bases of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption: A review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 16, 29–43 (1984).

Google Scholar

-

Greer, B. K., O’Brien, J., Hornbuckle, L. M. & Panton, L. B. EPOC comparison between resistance training and high-intensity interval training in aerobically fit women. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 14, 1027–1035 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Jung, W. S., Hwang, H., Kim, J., Park, H. Y. & Lim, K. Comparison of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption of different exercises in normal weight obesity women. J. Exerc. Nutrit. Biochem. 23, 22–27 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. Hybrid-type, multicomponent interval training upregulates musculoskeletal fitness of adults with overweight and obesity in a volume-dependent manner: A 1-year dose-response randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 23, 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.2025434 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Batrakoulis, A. et al. High-intensity interval neuromuscular training promotes exercise behavioral regulation, adherence and weight loss in inactive obese women. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 20, 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1663270 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Blackmore, D. G. et al. Long-term improvement in hippocampal-dependent learning ability in healthy, aged individuals following high intensity interval training. Aging Dis. https://doi.org/10.14336/ad.2024.0642 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Hawley, J. A., Hargreaves, M., Joyner, M. J. & Zierath, J. R. Integrative biology of exercise. Cell 159, 738–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.029 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Batacan, R. B. Jr., Duncan, M. J., Dalbo, V. J., Tucker, P. S. & Fenning, A. S. Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 51, 494–503. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095841 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Tsuji, K., Xu, Y., Liu, X. & Tabata, I. Effects of short-lasting supramaximal-intensity exercise on diet-induced increase in oxygen uptake. Physiol. Rep. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13506 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Ormsbee, M. J., Bach, C. W. & Baur, D. A. Pre-exercise nutrition: the role of macronutrients, modified starches and supplements on metabolism and endurance performance. Nutrients 6, 1782–1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6051782 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Broad, A. A., Howe, G. J., McKie, G. L., Vanderheyden, L. W. & Hazell, T. J. The effects of a pre-exercise meal on postexercise metabolism following a session of sprint interval training. Appl. Physiol. Nutrit. Metab. = Physiol. Appliquee Nutrit. Metab. 45, 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2019-0510 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Aagaard, P. et al. A mechanism for increased contractile strength of human pennate muscle in response to strength training: Changes in muscle architecture. J. Physiol. 534, 613–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00613.x (2001).

Google Scholar

-

Van Every, D. W., D’Souza, A. C. & Phillips, S. M. Hormones, hypertrophy, and hype: An evidence-guided primer on endogenous endocrine influences on exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 52, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1249/jes.0000000000000346 (2024).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the School of Physical Education of Shenzhen University and the relevant participants for their support. This study was funded by the Science and Technology Innovation Project of the General Administration of Sport of China (ID: 22KICX035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YBQ:Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft. CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing–review and editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft. ZCQ: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. WXD: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

BaiQuan, Y., Meng, C., Congqing, Z. et al. The effects and post-exercise energy metabolism characteristics of different high-intensity interval training in obese adults.

Sci Rep 15, 13770 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98590-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Whole-body HIIT

- Jump rope HIIT

- Body composition

- Muscle fitness

- EPOC

- Obese adults

Sports

USC Women’s Volleyball Falls to Cal Poly in NCAA Second Round Bout

KEY PLAYERS

- Fr. OPP Abigail Mullen led all scorers with 21.5 points earned on a match-high 17 kills (7e, 39att, .256) to go with 10 digs for her eighth double-double. She also had five blocks and two service aces.

- Fr. S Reese Messer put up her 11th double-double with 46 assists and 11 digs. She also added six blocks (one solo) and had three kills on eight swings (.375).

- RS So. OH London Wijay had 10 kills (3e, 38att, .184) and 12 digs for her eighth double-double (17th career).

- RS So. MB Leah Ford had nine kills (1e) on 17 swings to hit .471 and led the team with seven blocks.

- So. MB Mia Tvrdy played just the last three sets but finished with eight kills on 10 swings (.800) and had two blocks, two digs and a two-handed jump-set assist on a kill by Mullen.

- Sr. MB Rylie McGinest had six kills (1e, 13att, .385) to go with one block.

- Fr. LIB Taylor Deckert led the team with 13 digs and added six assists. Sr. LIB Gala Trubint had four digs and a service ace.

- For the Mustangs, Emma Fredrick led with 17 kills and had 17 digs to lead all players. Kendall Beshear and Annabelle Thalken each had 12 kills. Beshear had 14 digs for the double-double and served a pair of aces. Emme Bullis put up 44 assists with 12 digs for a double-double.

HOW IT HAPPENED

- The Mustangs never trailed in the opening frame to grab a 25-19 win. Both teams registered 15.0 points, but the Mustangs committed fewer unforced errors to come out on top. The Trojans had 13 kills with five from McGinest but hit just .146 with seven errors on 41 swings. Cal Poly had just 11 kills but hit .258 and had a 3-1 edge in blocks. Both teams each served an ace, but the Trojans served six errors to the Mustangs’ two in the loss.

- The teams were tied 13 times and the lead changed hands five times before Cal Poly took a 2-0 lead with a 25-20 win in set two. Mullen had five kills to lead the Trojans, but USC totaled just 10 kills and hit .147 in the set. Both teams had three blocks apiece, but the Mustangs still hit .270 with 15 kills (5e) on 37 swings with five more kills from Beshear.

- USC secured a 25-20 set-three win on the second of two service aces from Dani Thomas-Nathan. Tvrdy came in and sparked the Trojans with the first kill of the frame and finished with five on just six swings. Mullen tallied six kills on 12 swings without an error and helped USC hit .326 (18k, 4e, 43att). The Trojans had four blocks to help hold the Mustangs to a .194 attack rate with 10 kills (4e) on 31 swings. USC never trailed and led by five twice before winning by five.

- Back-to-back Mustang errors broke the eighth and final tie of the fourth and put the Trojans in front, 11-9, en route to a 25-14 win. USC continued to push and moved in front by six, 17-11, on a block by Mullen and Ford. Back-to-back kills from Mullen put USC on top by seven, 19-12, and her tool kill made it a 10-point USC lead at 23-13. Mullen and Wijay each scored four kills in the fourth as the Trojans hit .448 (14k, 1e, 29att) and had three blocks to hold Cal Poly to a .081 hitting percentage with 12 kills (9e) on 37 attacks.

- Cal Poly broke a three-all tie in the fifth with a 6-0 run and was never threatened on the way to a 15-7 win to seal the 3-2 win. Beshear had a six-serve run that included a service ace to put the Mustangs on top by six, 10-4. The Trojans could get no closer than within five despite every effort. The Mustangs hit .316 with eight kills (2e) on 19 swings over USC’s .091 rate in the fifth with five kills (3e) on 22 attempts.

MATCH NOTES

- USC fell to 13-6 all-time against Cal Poly. The teams met for the first time since 2012.

- The Women of Troy fell to 15-4 at home this season and to 231-64 (.783) all-time at Galen Center, which includes a 21-5 mark in NCAA tournament matches.

- USC goes to 131-45 (.744) all-time in the postseason with an 85-38 (.691) mark in the NCAA tournament.

- The Trojans fell to 14-11 in the second round of the NCAA tournament.

For more information on the USC women’s volleyball team and a complete schedule and results, please visit USCTrojans.com/WVB. Fans of the Women of Troy can follow @USCWomensVolley on Facebook, X, TikTok, and Instagram.

Sports

Indiana volleyball vs Colorado NCAA tournament final score, game updates, next

7:57 pm ET December 5, 2025

When does Indiana volleyball play next? Indiana volleyball next game, opponent in NCAA tournament

Aaron Ferguson

Details are still to come on the next weekend of the NCAA tournament. The certainties: IU is headed to Austin, Texas as UT hosts that quadrant as the No. 1 seed. The first and second rounds in Austin will finish Saturday night. No. 8-seed Penn State awaits the winner of Texas and Florida A&M in Saturday’s second round match.

7:55 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball celebrates Sweet 16 berth

Aaron Ferguson

Here’s how it looked as IU won its second-round match against Colorado:

7:50 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball highlights in win vs Colorado

Aaron Ferguson

Here’s a look inside Wilkinson Hall for IU’s win:

7:42 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball stats in win vs Colorado

Aaron Ferguson

The Hoosiers hit .378 for the match and had an 11-2 blocking advantage against the Buffs. The serving pressure wasn’t there like it was against Toledo, but IU played solid defensively and were able to clinch its second Sweet 16 appearance — its other was 15 years ago in 2010.

Candela Alonso-Corcelles led the way with 16 kills with just one error on 27 swings, an efficient .556. Freshman Jaidyn Jager added 15 kills (.375). The middles did plenty of work with Madi Sell having seven blocks and Victoria Gray adding four. Avry Tatum also had five blocks with eight kills. Setter Teodora Krickovic had 29 assists, eight digs and three blocks.

Colorado hit .208 for the match, led by Ana Burilovi’s 19 kills (.239) and an efficient seven on 11 swings for Cayla Payne (.545). But nine service errors did not help the Buffs, particularly with five in the first set.

7:34 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball score, result today vs Colorado in NCAA tournament

Aaron Ferguson

The Hoosiers are onto the regional semifinal with a 25-20, 25-17, 25-23 victory over Colorado. Quite a season by Steve Aird’s Hoosiers who now have a program-best 25 wins, and set it at Wilkinson Hall as the Hoosiers put their name on the bracket that their student section is holding.

7:30 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball scoring run takes lead on Colorado

Aaron Ferguson

Six straight points gives IU a 23-22 lead, two points away from a sweep of Colorado and advancing to the Sweet 16. A timeout by Colorado to try and stop the run.

7:27 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball score tonight vs Colorado

Aaron Ferguson

The crowd at Wilkinson Hall erupts with each point during this 3-0 IU run to cut the Colorado lead to 22-20 in the third set, trying to keep a sweep alive.

7:20 pm ET December 5, 2025

Colorado taking charge against Indiana volleyball

Aaron Ferguson

This third set was tied at 11 but Colorado has slowly clawed to an 18-15 lead, in need of a reverse sweep to keep its season alive. Steve Aird takes a timeout to try and slow the Buffs’ momentum.

7:15 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball score vs Colorado in NCAA tournament today

Aaron Ferguson

Colorado is playing its best set yet, tougher defensively and efficient offensively. It wins the race to the media timeout, taking a 15-13 lead on IU. The Buffs are hitting .471 to IU’s respectable .316.

7:10 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball score today vs Colorado in NCAA tournament

Aaron Ferguson

The Buffaloes have come out more energized and playing at a slower pace than what IU would like to play, and it’s worked out to an 8-6 lead, needing a reverse sweep to keep their season alive.

6:58 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball score tonight vs Colorado

Aaron Ferguson

The Hoosiers have taken the first two sets, going 25-17 in Set 2. IU had six blocks in the set to take a commanding 7-1 lead in that category, and it is siding out 73.7% of the time. Indiana has not yet lost a set in the NCAA tournament.

IU hit .458 in that set and Candela Alonso-Corcelles has a match-high 12 kills (.524). Their fast-paced offense has kept Colorado out of system. The Buffs are hitting .177 after an .062 in the second set. Ana Burilovi has 10 kills (.172).

6:47 pm ET December 5, 2025

Score of Indiana volleyball game against Colorado

Aaron Ferguson

IU wins the race to the media timeout with a 15-12 lead. Hoosiers are hitting .294 and Candela Alonso-Corcelles already has nine kills.

6:42 pm ET December 5, 2025

Munster native Sarah Morton strong defensively for Colorado at IU

Aaron Ferguson

Sarah Morton is wearing the gray libero shirt for Colorado and has had a solid showing so far with six digs and three assists so far. Indiana is up 11-10 in the second set.

6:30 pm ET December 5, 2025

Score of Indiana volleyball game today vs Colorado in NCAA tournament

Aaron Ferguson

The Hoosiers take the first set 25-20 after trailing 5-2 at one point. Quite the turnaround for the Hoosiers who settled in with their defense, which fueled their offense.

Steve Aird took a timeout and that set up Candela Alonso-Corcelles, who had a team-high seven kills (.538). IU benefitted from five service errors by Colorado, too. IU hit .353 to Colorado’s .300.

6:21 pm ET December 5, 2025

Colorado takes timeout as Candela Alonso-Corcelles heats up for Indiana volleyball

Aaron Ferguson

“I want Candy,” the fans inside Wilkinson Hall chant as Candela Alonso-Corcelles has a pair of kills into a Colorado timeout. IU leads the first set 18-13.

6:18 pm ET December 5, 2025

Colorado forced to take timeout to slow down IU volleyball run

Aaron Ferguson

The Hoosiers have now scored five straight points to take a 13-11 lead. They were trailing early and game flow was tough. Colorado has four service errors and IU has three. Hoosiers hitting .214 to Buffs’ .176.

6:15 pm ET December 5, 2025

Score of Indiana volleyball NCAA tournament game vs Colorado

The Buffaloes continued to build their lead, but it is four straight points for the Hoosiers to take a 12-11 lead in the first set.

6:07 pm ET December 5, 2025

Colorado uses early challenge after hot start against Indiana volleyball

Aaron Ferguson

The Buffaloes had a 4-1 start to this opening set but IU answered with a pair, though Colorado is looking for a block touch on a ball that sailed out.

6:01 pm ET December 5, 2025

First serve on deck for Indiana volleyball vs Colorado in NCAA tournament

Aaron Ferguson

Starting lineups are wrapping up and the match will be underway in minutes.

5:45 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana volleyball versatility makes IU difficult to defend against

Aaron Ferguson

From senior Candela Alonso-Corcelles to freshman Jaidyn Jager and her high school teammate Avry Tatum, the Hoosiers showed how versatile and multiple they can be, which gives coach Steve Aird a reason to be at ease.

5:30 pm ET December 5, 2025

How IU volleyball advanced played in first round of NCAA tournament vs Toledo

Here’s a look back at IU’s victory over Toledo on Thursday night, setting the program’s single season wins record in the process.

5:15 pm ET December 5, 2025

Charlotte Vinson’s miraculous journey from life support

Aaron Ferguson

Yorktown’s Charlotte Vinson has found a role as a serving specialist, pressuring teams with her top-spin serve. But she’s undergone a miraculous journey to even find the floor again after being placed on life support last year.

IndyStar’s Brian Haenchen followed Vinson’s journey to returning and wrapping up her high school career as the No. 21 recruit nationally.

5:00 pm ET December 5, 2025

IU volleyball has Kona Bear the dog that helps with mental health

Aaron Ferguson

Woman’s best friend, Kona Bear, has been an instrumental part to the makeup of the Hoosiers. A service dog trained to help with anxiety brings joy to IU volleyball.

4:45 pm ET December 5, 2025

Indiana setter Teodora Krickovic among talented freshmen

Aaron Ferguson

Teodora Krickovic, a freshman from Serbia, has been an integral part of IU’s growth and is one of the members of a talented freshman class. She, along with Victoria Gray, were an impressive of that standout recruiting class.

Here’s more on Krickovic and Gray, who were standouts in the Monon Spike match:

4:30 pm ET December 5, 2025

Candela Alonso-Corcelles is IU volleyball’s winningest player

Aaron Ferguson

The starting senior on the outside is Candela Alonso-Corcelles, who committed to IU because of the family feel. She’s also fostered that same culture into the Hoosiers as part of a historic run. She’s a native of Madrid, Spain, and is a rare fourth-year senior all at one school.

Here’s more on Alonso-Corcelles:

4:15 pm ET December 5, 2025

How did IU volleyball make NCAA tournament

Aaron Ferguson

A blend of freshmen — IU’s highest-rated class — and veterans make up a roster seeing unprecedented success on individual and team levels. They Hoosiers have reached a number of program bests in Big Ten play, and can set a single-season wins record by beating Toledo.

Here’s more insights from IU on how this happened:

4:05 pm ET December 5, 2025

What time Indiana volleyball play in the NCAA tournament? Start time for IU volleyball vs Colorado

First serve is scheduled for 6 p.m. at Holloway Gymnasium.

4:01 pm ET December 5, 2025

Where to watch Indiana volleyball in the NCAA Tournament; what channel is IU volleyball on tonight, Dec. 5?

Aaron Ferguson

ESPN+

Watch IU volleyball on ESPN+

Our team of savvy editors independently handpicks all recommendations. If you purchase through our links, the USA Today Network may earn a commission. Prices were accurate at the time of publication but may change.

Sports

Kansas women’s volleyball vs Miami (Fl.): NCAA tournament final result

Updated Dec. 5, 2025, 8:26 p.m. CT

LAWRENCE — Kansas women’s volleyball went up against Miami (Fl.) on Friday at home during the second round of the NCAA tournament, and came away with a four-set victory to advance to the Sweet 16.

The Jayhawks entered as the No. 4 seed, after a three-set win at home in the opening round against High Point. The Hurricanes were the No. 5 seed, and arrived after a four-set win against Tulsa. KU was the host team for this contest.

Here is what happened inside the Horejsi Family Volleyball Arena:

UPDATE: 8:13 p.m. (CT): Kansas wins in 4 sets

4th Set

UPDATE: 8:11 p.m. (CT): Kansas wins 4th set 27-25

UPDATE: 8:05 p.m. (CT): Kansas leads 22-20 in 4th set

3rd Set

UPDATE: 7:34 p.m. (CT): Miami (Fl.) wins 3rd set 25-22

2nd Set

UPDATE: 7 p.m. (CT): Kansas wins 2nd set 25-22

UPDATE: 6:54 p.m. (CT): Kansas and Miami (Fl.) are tied 17-17

1st Set

UPDATE: 6:27 p.m. (CT): Kansas wins 1st set 25-17

UPDATE: 6:14 p.m. (CT): Kansas leads 7-5 in 1st set

Pregame

Here are the starters

Kansas prepares for matchup

Kansas women’s volleyball vs Miami (Fl.) matchup time

- Date: Friday, Dec. 5

- Time: 6 p.m. (CT)

- Location: Horejsi Family Volleyball Arena in Lawrence

What channel is Kansas women’s volleyball vs Miami (Fl.) matchup on today?

Kansas women’s volleyball’s NCAA tournament matchup against Miami (Fl.) will be broadcast on ESPN+ in 2025. The Jayhawks have a chance to advance in the NCAA tournament. Streaming options include ESPN+.

Kansas women’s volleyball vs Miami (Fl.) score

Jordan Guskey covers University of Kansas Athletics at The Topeka Capital-Journal. He was the 2022 National Sports Media Association’s sportswriter of the year for the state of Kansas. Contact him at jmguskey@gannett.com or on Twitter at @JordanGuskey.

We occasionally recommend interesting products and services. If you make a purchase by clicking one of the links, we may earn an affiliate fee. USA TODAY Network newsrooms operate independently, and this doesn’t influence our coverage.

Sports

Former UH volleyball player, youth coach accused of producing child porn

HONOLULU (HawaiiNewsNow) – A former youth volleyball coach who played on the University of Hawaii men’s volleyball team was arrested and charged with production of child pornography, allegedly with a former player.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office, District of Hawaii, announced Friday that Elias David, 37, of Waimanalo, was charged by criminal complaint on Dec. 3.

He was employed as a firefighter for the Department of Defense and worked at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Federal Fire Station 9.

According to the criminal complaint filed by the FBI, a 17-year-old told her aunt she was having sexual intercourse with David, who was a family friend and her volleyball coach since she was 13 years old.

Court documents said the teen’s relationship began with David in 2023 after a volleyball trip to Las Vegas. She was 16 at the time.

The teen told investigators that David was providing extra training to prepare her for college. She also admitted to engaging in different types of sexual contact with David that including oral and vaginal sex, documents said.

She also said that their sexual activities occurred at the fire station where he worked, at a nearby warehouse, as well as at David’s home and vehicle, documents said.

David was arrested in July of 2024 for sexual assault in the second degree. He waived his Miranda rights and was interviewed.

During his interview with investigators, David said they “began to develop feelings for each other and ‘fell in love,’” and admitted that he and the teen engaged in a sexual relationship, documents said.

David said that the romantic phase of the relationship began around March 2023, and admitted to ordering ride share services for the teen so she could leave her house to meet him at or near his workplace, documents said.

Investigators said they found 97 graphic videos of the two of them on her phone and 78 emails referring to ride share trips and GPS location data.

David played for the University of Hawaii men’s volleyball team in 2009.

If convicted, he could face up to 30 years in prison.

Copyright 2025 Hawaii News Now. All rights reserved.

Sports

Iowa State Tops St. Thomas, Advances to Second Round

MINNEAPOLIS, Minn. – No. 23 Iowa State (23-7, 12-6 Big 12) won in five against St. Thomas (21-10, 11-5 Summit) in the NCAA Championship First Round Friday night. No. 5-seed ISU advances to the second round to meet the winner of No. 4-seed Minnesota vs. Fairfield tomorrow at 7 p.m.

After St. Thomas took the first 25-21, ISU answered outhitting UST .552-.143 in the second to tie up the match with a set score of 25-13. The Cyclones took the match lead after another dominant set score of 25-16, but St. Thomas would win the fourth 25-21 to extend the match to a fifth. ISU used a 7-0 run in the fifth to flip the momentum and seal the victory.

Big 12 Libero of the Year Rachel Van Gorp was her usual self and had her third-straight match with 20 or more digs, ending the night with a career-high 33. The total is the second-most in an NCAA Tournament match by a Cyclone, and most since 2012. It was also match No. 35 in a row with double-figure digs and her 50th-career match in double figures.

Iowa State had a dominant night at the service line, serving to the fourth 10-plus ace match this season, and 28th of Christy Johnson-Lynch‘s career with 12 through the night. ISU was led by Nayeli Ti’a with five aces to tie the NCAA Tournament school record, while Van Gorp had four, now the second-most in a tournament match.

Alea Goolsby had her 15th match this season with 10-plus kills, leading ISU with 15. Ti’a delivered 14 kills for her 13th match this season with 10-plus, and Lilly Wachholz (12) and Amiree Hendricks-Walker (10) made for four in double figures.

SET ONE

At 6-6, Morgan Brandt tricked St. Thomas with a setter kill while Tierney Jackson served up an ace but UST followed to again knot the score. The Tommies flipped the lead at 11-10 and took the next two as Iowa State called the first timeout. Ti’a slammed down her second kill out of the timeout, but St. Thomas kept with the lead reaching 20 first (20-17). ISU cut its deficit to one at 22-21, but the Tommies ended the first on a run of three for the set win.

SET TWO

Ti’a had a no-doubt kill to make it 1-1, while the Tommies denied ISU the lead while going up 4-2. Goolsby’s third kill tied it, and the Cyclones took their first lead at 6-5 on a block. UST flipped the advantage in its favor briefly, but ISU set out on an 11-0 run to take it right back and run ahead 18-8. A Brandt ace put the Cyclones at set point and an attack error by the Tommies sealed the set at 25-13. ISU did not have a single attack error in the frame.

SET THREE

Back-to-back aces by Ti’a brought Iowa State ahead 6-2, while Ti’a delivered another bringing the scoreboard to 9-2. Goolsby’s seventh kill at .400 capped a Cyclone run of seven on the next play, but a UST scoring run of four came soon after as the Tommies came within three (13-10). Iowa State had a run of four of their own to keep command of the lead, while the Cyclones took the match lead on Goolsby’s 10th kill at 25-16.

SET FOUR

A 4-0 scoring run took the Tommies ahead 7-3 as ISU then called an early timeout. Iowa State would go on to knot the score at 13s on yet another ace by Ti’a, while a UST attack error gave ISU its first lead of the set. That lead was not safe as the Tommies went ahead 19-15 to cause Iowa State’s final timeout of the set. The Cyclones had a late run of three, but St. Thomas pushed on to force a fifth at 25-21.

SET FIVE

Iowa State took the first point on a kill by Ti’a, but St. Thomas followed going ahead 5-2. ISU did not let up, hitting a run of four to take a 6-5 lead and cause a UST timeout. The run stretched to seven as Iowa State switched sides with the lead of 8-5, and Goolsby capped the run next with a kill. ISU would go on to win it 15-8 after a St. Thomas service error.

Sports

Updates, highlights as Wisconsin advances with sweep vs North Carolina

9:43 pm CT December 5, 2025

See some highlights from Wisconsin’s NCAA tournament win vs North Carolina

John Steppe

9:39 pm CT December 5, 2025

Mimi Colyer’s stats vs. North Carolina in second round of NCAA tournament

John Steppe

- 22 kills

- 5 attack errors

- 42 total attacks

- .405 hitting percentage

- 13 digs

- 3 blocks

9:37 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin vs. North Carolina NCAA tournament final stats comparison

John Steppe

- Kills: Wisconsin 60, North Carolina 37

- Hitting percentage: Wisconsin .365, North Carolina .233

- Service aces: Wisconsin 2, North Carolina 0

- Service errors: North Carolina 5, Wisconsin 8

- Digs: Wisconsin 56, North Carolina 40

- Total team blocks: North Carolina 6, Wisconsin 5

9:33 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin coach Kelly Sheffield comments on Badgers’ NCAA tournament win vs. North Carolina

John Steppe

8:42 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin finishes off sweep, advances to regional semifinals

John Steppe

After 19 ties and 10 lead changes, Wisconsin completes the sweep with a 27-25 win in the third set against North Carolina. It was another special performance by Mimi Colyer, who finished with 22 kills.

Wisconsin is headed to the regional semifinals for the 13th consecutive season. We’ll see what happens elsewhere in the Texas regional, but second-seeded Stanford will be the most likely Sweet 16 foe in Austin.

8:34 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin and North Carolina tied at 22-22 in third set

John Steppe

Wisconsin and North Carolina are tied at 22-22 in the third set. There have been 17 ties and seven lead changes in this set after having only two ties and one lead change in the first two sets combined.

8:22 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin, North Carolina have back-and-forth start to third set

John Steppe

After a relatively uneventful first two sets, there have already been nine ties and four lead changes in the third set. Wisconsin has a narrow 15-14 lead at the media timeout. North Carolina already has more kills in the third set (11) than the Tar Heels did in either of the previous two sets (10).

8:01 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin takes second set vs. North Carolina, 25-21

John Steppe

The second set was not quite as pretty as the first set, but Wisconsin did enough to win it 25-21 and take a 2-0 set lead. Grace Egan finished it off with her seventh kill of the night.

After committing only two attack errors in the first set, Wisconsin committed six attack errors in the second set.

Mimi Colyer continues to be competing at an elite level, as she is now up to 16 kills while hitting .429. For perspective, the entire North Carolina team has 20 kills while hitting .187.

7:46 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin has 15-10 lead in second set, Mimi Colyer now has 14 kills

John Steppe

Mimi has already six kills in the second set, boosting her total so far tonight to 14 kills. Wisconsin has a 15-10 lead in the second set.

7:29 pm CT December 5, 2025

Wisconsin takes first set vs. North Carolina, 25-14

John Steppe

Wisconsin, facing one of the better defensive teams in the country, hit .400 en route to a 25-14 set win to open its second-round match. The Badgers clinched the set with a great setter dump by Charlie Fuerbringer to cap off a 4-0 scoring run.