7 Commonwealth campuses are slated to close by spring 2027 following a 25-8 vote from Penn State’s Board of Trustees. The closures, while controversial, reflect a broader set of data trends signaling deep structural challenges within the university’s regional system.

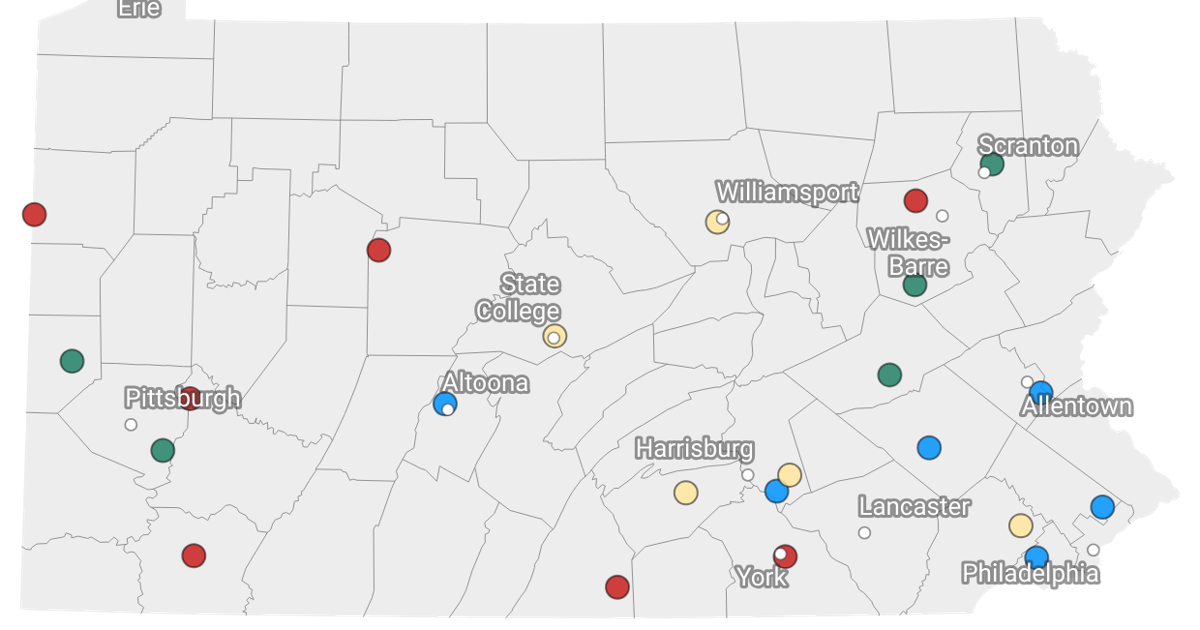

The decision targets DuBois, Fayette, Mont Alto, New Kensington, Shenango, Wilkes-Barre and York — locations that face significant enrollment declines, mounting financial deficits and costly infrastructure demands , according to the 143-page internal recommendation report.

Meanwhile, five other campuses initially proposed to close — Beaver, Greater Allegheny, Hazleton, Schuylkill and Scranton — will remain open with increased support.

The decision between staying open and closing came down to a combination of factors.

Enrollment decline and student outcomes

Across the 12 campuses under review, enrollment dropped 35% over the past decade. 7 of the 12 currently enroll fewer than 500 students.

Enrollment for the eight Commonwealth campuses that were initially marked safe — Abington, Altoona, Behrend, Berks, Brandywine, Harrisburg and Lehigh Valley and Great Valley — has dropped 22%.

At 10 of the campuses, more than 20% of classes have fewer than seven students enrolled, a figure that suggests unsustainable class sizes and poor economies of scale.

Graduation outcomes offer another lens through which Penn State assessed the viability of its regional campuses. Penn State Shenango, for example, has the lowest graduation rates among the campuses that were under review, with only 25.7% of students completing their degree within four years and 47.7% within six. Other campuses recommended for closure also show low rates. Wilkes-Barre stands out with a 69.9% six-year rate, but still has 42% of students graduating in four.

While these numbers aren’t the sole basis for closure, the report emphasizes the risk posed by high stop-out rates. At campuses like Fayette and DuBois, more than 30% of students leave without ever earning a degree. The disparity in student outcomes, particularly when paired with small enrollments and limited resources, raised serious concerns about whether these campuses could sustainably support students through graduation.

Demand vs. distribution

Though the closures affect only a small share of Penn State’s total enrollment, the contrast with university-wide demand, for some trustees, is striking and deeply frustrating.

In summer and fall 2023, Penn State received 128,201 first-year applications across all campuses. Of those, 16,239 enrolled, including 9,040 at University Park. That same year, 15,735 international students applied, but just 1,180 enrolled — with 651 at University Park alone.

At the Board of Trustees meeting on May 12, members repeatedly pointed to this gap between interest and access. Trustee Ted Brown argued that while students are eager to attend Penn State, the university isn’t successfully routing and matching them to where there is space.

Meanwhile, the seven campuses now slated for closure collectively enroll just 3.6% of Penn State’s student body, making them difficult to sustain in light of low demand and high overhead. According to the report, the campuses also employ 3.4% of Penn state faculty and 2.2% of its staff.

Demographic and regional decline

Most of the shuttered locations are situated in rural countries — regions already grappling with decades-long economic decline and now facing steep population losses. According to the report, 41 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties are projected to shrink by 2025, with rural counties expected to lose 5.8% of their total population.

Equally critical to campus viability is the sharp decline in the college-aged population. The number of residents aged 19 and under is projected to fall by 6.8% statewide by 2050, with sharper drops in already-depopulated regions.

Since Penn State’s Commonwealth campuses primarily serve local populations, demographic shifts translate almost immediately into enrollment losses. For example, at some campuses, up to 70% of students come from the home county, meaning even small declines in local high school graduates can significantly erode the applicant pool.

Some counties are facing extreme declines. Clearfield County, home to Penn State DuBois, is projected to lose nearly 10% of its youth population by 2050. Elk County, another key feeder region, is expected to see a 14.3% drop.

The data suggests not just a temporary dip, but a long-term structural challenge. For campuses without on-campus housing or broader regional draw, like Shenango and DuBois, the impact of these demographic shifts is even more acute.

Some of the campuses slated for closure serve noteworthy proportions of Pell Grant recipients, underrepresented minorities and first-generation students.

Penn State Wilkes-Barre, for example, 39% of students receive Pell Grants, 18% identify as underrepresented minorities and 44% are first-generation college students.

Similar trends appear at other campuses recommended for closure — such as Fayette, Shenango and York — where 38% of the student body are first-generation and over 30% receive Pell support, raising concerns about equity and access.

Big costs, bigger changes

Ultimately, the closures reflect a broader shift in Pennsylvania’s population map — one that increasingly favors urban and suburban regions over the rural communities that once sustained these local campuses.

The 12 campuses marked for closure account for $29 million in annual losses, a figure that balloons to $70 million when factoring in shared university overhead. The report also notes a combined $333 million in deferred maintenance, like updating facilities, across those campuses — costs Penn State would eventually need to cover if the campuses remained open.

The closures, according to Bendapudi, are part of a broader strategy to reallocate limited resources toward strong, more sustainable regional hubs — campuses with the capacity, location and enrollment momentum to serve students more effectively over the long term.

It’s a move she said was grounded in data, guided by institutional values and shaped by months of public feedback and deliberation.

Still, the emotional weight of the decision was palpable. Ahead of the vote, the Board of Trustees received 154 public comments, many of which argued that closing campuses in rural or underserved areas would undermine Penn State’s land-grant mission to provide accessible education statewide.

MORE NEWS CONTENT

Penn State is home to many students and staff who have a passion for raising climate awarene…