Longform

Decades of uneven investment have left Philly kids playing at a disadvantage, with consequences that stretch far beyond the game.

Get a compelling long read and must-have lifestyle tips in your inbox every Sunday morning — great with coffee!

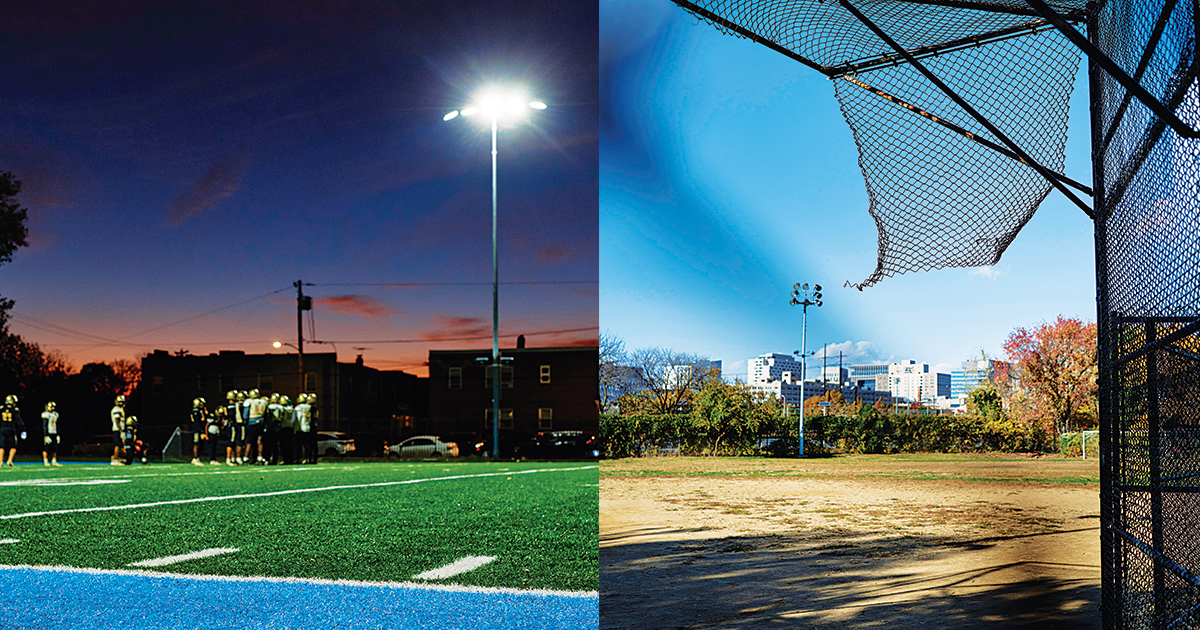

Field at Vare Recreation Center / Photography by Gene Smirnov

It is a warm September evening at the sparkling new $21 million Vare Recreation Center at 26th and Moore streets, home to the Sigma Sharks youth sports program. Neighborhood children romp around a sprawling playground as a DJ spins oldies, while three different football teams practice in different corners of the center’s multipurpose football/ soccer field. As teams of various ages run plays, younger siblings — the next generation of Sharks — dart about.

Before the new gridiron opened in late July, the six Sigma Sharks teams practiced and played as they always had, on an unkempt grass field strewn with rocks and dotted with large dirt patches and the occasional pile of dog feces. “It was dirty, and looked like it wasn’t taken care of,” says Caleb Williams, a member of the Sharks U13 (under-13) team and an eighth-grader at Christopher Columbus Charter School.

Not anymore. The new Vare field is a pristine vivid green, surrounded by a four-foot-wide bright blue border. “We call it the water,” says Tariq “Coach T” Long, who directs the U8 squad. “Once you cross the water, you’re in with the Sharks.”

And that’s a pretty good place to be these days. The Sigma Sharks, who have been around since 1992, sponsor the football teams plus a cheerleading program and four basketball squads, serving more than 300 kids. Sharks president Anthony Meadows says they love the new facility, which also boasts two gleaming indoor basketball courts. “When the kids saw it for the first time, they lost their minds,” says Kevin Mathis, a coach since 1997. (He calls himself “the longest-tenured Shark.”)

Since Vare can’t accommodate all six teams at once, some still practice and play at Smith Playground at 24th and Jackson. Meadows calls it “adequate.” Tanisha Perry, who brings her eight-year-old twin sons from West Philly to play, disagrees. Smith is dirty, she says, and “attracts the wrong crowd.” Vare, on the other hand, is safe, with clean bathrooms and omnipresent staff members.

“I want to be here, always,” she says.

You can see why. In Philly, Vare is a unicorn of a facility that materialized through a combination of funding from the city’s soda tax and a relentless champion in the form of City Council President Kenyatta Johnson. Johnson worked with former Philadelphia Eagle Connor Barwin’s Make the World Better Foundation on the project, which is in his district.

Most city districts (and rec centers, and kids) aren’t quite this lucky. A 2023 study by Temple University, commissioned by Philadelphia Parks and Recreation and managed by the Philadelphia Youth Sports Collaborative (a nonprofit consortium of youth sports providers and advocates that provides resources, support, and funding), looked at more than 1,400 sports facilities managed by Parks and Rec. Sixty percent of them were rated below or far below average. Eighty percent of athletic fields the kids play on aren’t stand-alone fields, but the outfields of baseball diamonds. On top of that, the Temple study found, facilities in neighborhoods with a larger percentage of white residents were of a higher quality.

It’s very much a two-tiered system. There’s a big gap between them.” — Beth Devine, executive director of the Philadelphia Youth Sports Collaborative

Zoom out a little more, though, and you see that that depressing inequity pales in comparison to the big and growing gulf between the youth sports climate in the city and that in many suburbs, where the fields, facilities, and infrastructure are … well, an entirely different ballpark. “In the suburbs, it’s not even a second thought,” says Meadows. “Kids just go to the fields and throw the ball around. Even if it’s a grass field, it’s nice. In the city, you get overused grass and dirt. And the turf fields are often locked up.”

“It’s very much a two-tiered system,” says Beth Devine, executive director of the PYSC. “There’s a big gap between them.”

She’s right about this … and then some. By now, we all know that youth sports as a whole are only getting more professionalized and more expensive as time rolls on, and that money is a real — and quickly expanding — fault line in and barrier to the world of kids athletics. (A July New York Times story about this very topic cited an Aspen Institute finding that the average U.S. sports family spent $1,016 on its child’s primary sport in 2024 — a 46 percent hike since 2019.) And the stakes of access to athletics are even higher than you might think — and affect more people than just kids and their families. Studies indicate that kids who play sports are better at problem-solving and self-regulation, and, as the Temple report showed, violent crime rates drop in neighborhoods that have youth sports facilities. The better the condition a field or court is in, Devine says, the less crime there is around it — across all types of neighborhoods.

Currently, only 25 percent of kids from U.S. households with annual incomes below $25,000 participate in youth sports, compared to 44 percent of kids from families with annual incomes greater than $100,000 — which makes it tough for sports to be any kind of great equalizer. Add to that the billionaires and private equity firms trying to get a piece of America’s $40 billion youth sports business, founding commercialized camps and leagues and tournaments that compete with and pull talent from even the most moneyed, polished suburban rec teams. All of which means that the chasm between the typical city neighborhood rec team and everyone else is only growing.

The statistics — and what they portend — can be overwhelming. It doesn’t seem like that’s going to change anytime soon.

But then … there’s Vare. Not as fancy as some of the more elite facilities you can find in the ’burbs, with a program not as structured or rigorous or polished — but a game-changer for the kids who play there. “A facility in their neighborhood that kids can call home,” as Meadows says.

“I want this to be normal for everybody,” he adds.

Which makes you think: In a city that loves and understands the value of its sports as well as Philly does — a city that produced Dawn Staley, Wilt Chamberlain, Mo’ne Davis; a city with rec teams that are out there winning championships and tournaments; a city with five (soon six) professional teams — why can’t it be the norm for everybody? Or maybe the more apt question right now, as we stare down a year that’s going to bring the world to our stoop to watch the World Cup, a PGA championship, the Major League Baseball All-Star Game, and the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, is this: How might we make it so, before the opportunity gaps — for the kids, for our city — yawn into infinity?

•

For eight years, Amos Huron has led the Philadelphia Youth Organization, which was founded in 1990 and encompasses the Anderson Monarchs program and its soccer, baseball, softball, and basketball teams. He believes the baseball/softball field at the Marian Anderson Rec Center — which the Monarchs also use as a multi- purpose field — is “probably the best in the city.” He’s likely right: When you walk by the field at 18th and Fitzwater, it’s hard to miss the gleaming, pristine outfield, complete with a warning track and bright yellow foul poles. The 3.4-acre facility also boasts basketball courts inside and out, and room for boxing and martial arts. There’s even an indoor baseball training facility, thanks to an assist from former Phillies star Ryan Howard a decade ago.

It’s still not close to many of its suburban counterparts.

Some 20 miles away, the 725 kids of the Newtown-Edgmont Little League play on seven grass diamonds, three of which have lights. The 15-year-old, 10,000-square-foot indoor Flanigan Center, part of the complex, was recently renovated and allows for winter workouts for NELL players and high school teams from the city and suburbs. An army of volunteers, unpaid coaches, and parents help keep the place running, as do local business sponsors: Levels range from $500 a year (Field Level Sponsor) up to $1,500 (Elite Level Sponsor, which comes with a large sign in the Flanigan Center and two baseball field signs). Even the snack bar is top-tier. “Some people eat there versus the local pizza place,” says coach and former president Daren Grande.

Not far from the NELL baseball universe, the Radnor-Wayne Little League, which will turn 75 in 2027, operates “at least” 12 fields that it leases from Radnor Township and its school district and serves between 900 and 1,000 kids in its baseball and growing softball leagues, according to president Tom McWilliams. Worth noting is that registration fees aren’t much different from a lot of what you see with leagues in the city. Those vary, but seem to hang between $100 and $250; Radnor-Wayne’s fees sit between $150 and $195, and NELL’s is $200.

On paper, Philly has far more assets than either of these townships, with 259 different city locations encompassing more than 1,500 fields and courts. But with all the kids across the city who play on one team or another (some 40 to 45 percent of Philly youth participate in “some structured activity program,” says Philly Parks and Rec director of youth sports Mike Barsotti), it’s not enough to meet the demand. In fact, access is the first problem many leagues face: Competition from adult leagues, travel outfits, high school teams — St. Joe’s Prep’s football squad has practiced on the Philly Blackhawks Athletic Club field in North Philly; Universal Audenried Charter High School practices at Vare — and other neighborhood programs creates scheduling and permitting challenges. The city’s permit process favors neighborhood organizations, but if they don’t register in time, other groups get the chance to sign up (and they’re usually more organized and quicker to fill out requests, says Barsotti). And when new fields open, they reach capacity almost immediately. At the South Philadelphia Super Site turf football field at 10th and Bigler, games are scheduled to the minute during the season, says Adam Douberly, a father to three rec-league athletes. Kids get one hour, exactly, on the fields, playing times vary, and games can end as late as 10 p.m.

Even the popular 1,200-player Philadelphia Dragons Sports Association (formerly the Taney Youth Baseball Association, home to the team that played in the 2014 Little League World Series), which recent president John Maher says has “a relatively affluent demographic, mostly in Center City,” can’t find sufficient field space, and “100 percent” has facility envy when it faces suburban teams in District 19 Little League competition. (Right now the Dragons’ biggest challenge, he says, is finding fields for its burgeoning coed flag football program.)

All of this use (and overuse) helps lead to the second big issue: maintenance. “The city budget to maintain the fields is close to zero, so the fields may start off with grass, but at the end of the season, they are dirt pits,” says Liam Connolly, executive director of Safe-Hub Philadelphia, which provides soccer opportunities for kids ages four to 18 in the Kensington area.

Douberly’s boys play in the Dragons program, which plays at FDR Park and Markward Playground in Schuylkill River Park, among other spots. Markward, he says, “is completely overgrown. It’s like bouncing a baseball on a concrete floor.” Playing on fields of that caliber, especially for those who know there is something better out there, isn’t just harder. It’s dispiriting.

City fields in disrepair at Markward Playground

“The kids would go to other places and see all of [the nice facilities] when their field was dust and rocks,” Meadows says about the Sharks, pre–Vare glow-up.

Curt De Veaux, a Monarchs coach who also runs the City Athletics soccer program with his wife, Janea, is trying to introduce soccer to kids across Philly. He agrees that it’s hard to find places to play. And at Germantown’s Mallery Rec Center, where he directs City Athletics, “I’ve personally paid to get the grass cut and lines put on our field,” he says. (Barsotti, who notes that the department’s mowing contract is upwards of $3 million a year, says cuts are scheduled weekly during the seasons: “Some groups choose to mow more frequently to keep the grass the length they want and ensure it’s cut fresh for their games.”)

It’s not just the field and facility quality teams grapple with, either: A third issue is that the lack of infrastructure and financial resources within grassroots organizations means, across all kinds of teams, that there’s often not much room for strategic planning or coach training, or the ability to travel to seminars and conferences that provide information on new leadership techniques.

De Veaux would say that his goals for City Athletics are even more modest than that: He mostly wants to grow his reach across the city, to get more kids acquainted with the basics so they can grow into players who love the sport and can compete if they want. When it comes to competition, he knows what’s out there. As a longtime coach, he’s spent time in the past meeting with members of the suburban soccer powerhouse FC Delco — a regional force and travel league that plays a national schedule and includes many of the best players from the area — to learn more about how to run a high-end program.

FC Delco, which started in the 1980s in Delaware County, now has main hubs in Downingtown and Conshohocken with about 10 fields between them, plus more than 60 paid, certified coaches and some 1,700 boys and girls on 112 teams. Many of its players are from the suburbs, but some city kids make the trek, general manager Rob Elliot says. Money is another potential barrier for kids. Travel costs for the teams can run into the thousands each year, though the club does provide some financial aid and partners with the JT Dorsey Foundation, which offers soccer opportunities for kids in impoverished areas across Pennsylvania.

De Veaux, meanwhile, says his meager resources allow for only limited growth. And overall lack of infrastructure and resources in local and grassroots organizations just “widens that gap,” as he says, between those teams and the FC Delcos of the world. And the bigger that gap gets, the worry goes, the more kids and families are likely to opt out of city programs like his. Or just opt out of sports entirely.

•

At a time in the 1980s and 1990s when youth sports were on the rise, Philadelphia’s dire city budget shortfalls left no room for investment in recreational spaces, while in townships and neighborhoods outside the city, programs grew and thrived. Still today, many of the surrounding towns have real funding advantages, even as most leagues receive no money from the townships in which they’re based. They exist (and in some cases, excel) thanks to registration fees, donations, and sponsorships. Media Little League president Andrew Tamaccio says that league “has 100 local sponsors, if not more.” Marple Township Little League, with 360 kids, has a slew of sponsors too, and significant community support that helps keep the fields mowed, the lines chalked, and the snack bar stocked.

While it’s true that leagues in less moneyed townships face many of the same issues as their city counterparts, by and large, the differences between the suburbs and the city — between leagues with cash and those without — are real, and the gap is wide, the Sharks’ Meadows says. Though that doesn’t mean there isn’t real talent in the city rec leagues, and real successes. The Blackhawks in North Philly have won five national gridiron titles, the Sharks have won “several championships,” Meadows says, and the Frankford Chargers U8 football team captured a 2024 national title.

But competition is getting stiffer on and off the field.

As the July Times story detailed, the expense and expectations of youth sports are on a steady rise: expense in the form of ever more elite travel teams, gear, camps, and tournaments; expectations in the sense that parents increasingly are looking for returns on their (significant) investments in the form of college scholarships. Not exactly a sure bet, when you consider that the odds of a high school player even making a Division I hoops roster are 110:1, according to data from the NCAA. It’s 108:1 for soccer, 43:1 for baseball, and 33:1 for football.

Meanwhile, PYSC’s Devine frets, the abundance of travel teams and the overall shift we’re seeing toward ever more elite athletic experiences “has sucked the life out of youth and rec-league programs.”

It was in this sports climate and moment that board members of three different city soccer organizations — Fairmount, Philadelphia City FC (formerly Palumbo), and United Philly — decided to rally. In February of 2025, they voted to combine and form the Philadelphia International FC (known as Inter Philly) in hopes of replicating something like the FC Delco model.

“We want to provide people who live in the city with a competitive environment similar to what is available in the suburbs,” says Connor Robick, the group’s co- executive director. They currently work with nearly 4,000 kids (about 850 players on 53 travel squads, the rest in recreational play), ages two to 19, all over the city, from introductory training (which starts at $140 for an eight-week program) to highly competitive travel squads (which can run between $1,650 and $2,100). It has home fields at the Edgely Fields in Fairmount Park, Cristo Rey Philadelphia High School and the Salvation Army Kroc Center in North Philly, and the South Philly Super Site and Palumbo.

As with many of the suburban and travel teams, Inter Philly fundraises with and seeks sponsorships from local businesses to offer up to $300,000 annually in financial aid to its team members. Of course, Robick says, the organization is always looking to raise more cash and do more.

Other city programs and rec leagues have similar funding aims and challenges. “I beat the bushes to find money,” Meadows says of his efforts in South Philadelphia.

South Philly Sigma Sharks president Anthony Meadows

There’s also been a continuous push by Barsotti and other city parks officials, as well as community members, to increase rec center staff so that there are enough people to help with programs “from sports to arts to after-school,” Barsotti says. But it’s hard finding — and paying — enough qualified people. When suburban soccer clubs are paying U9 coaches $65 an hour, he says, it’s tough — nay, impossible — for the city to match it. It’s often up to the community to provide volunteers to make things run smoothly, another hard task.

You might be thinking now: What about the Philadelphia Beverage Tax, aka the soda tax? Wasn’t that supposed to help chip away at this very thing? Mayor Jim Kenney’s nine-year-old tax has actually brought in nearly $600 million in revenues. Nearly 40 percent of that money has gone — as planned — to fund operating expenses and the city’s also crucial preschool expansion, while money earmarked to revamp and renovate parks, libraries, and rec centers (the Rebuild initiative) doesn’t extend to the operations of those places.

Still, there has been progress in improving facilities and fields. Vare, for one example. As of press time, 39 sites have seen a revamp at some level — new turf fields at Murphy Recreation Center in South Philly, a freshly sodded football field at Chew Playground in Point Breeze, upgraded basketball courts at 8th and Diamond Playground in North Philly. Another 14 are under or preparing for construction right now.

It’s also worth noting that revenues from the tax have fallen short of the $92 million-per-year projection (the 2023 total was $72.7 million). Even so, this year, Barsotti says, youth sports did manage to get a bit of an unexpected windfall in the form of an extra $3 million in the budget for fiscal year 2025. The cash went into equipment (basketballs, soccer balls, portable scoreboards, volleyball poles), coach training through a program with PYSC, and grants for community sports organizations. It might be a small sign of better times to come; in the run-up to her election, Mayor Cherelle Parker said she’d like to at least double the Parks and Rec budget by the end of her first term (to help catch up from those budget shortfalls of the ’80s and ’90s). This would surely help get more playing spaces up to snuff, though the actual numbers still don’t inspire a huge amount of optimism when you compare them to those in other cities. Chicago’s 2025 budget included $598 million for parks and rec; New York’s was $582.9 million. Dallas’s 2026 budget has $118.4 million slated for the parks department, and in Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser’s most recent budget included $89 million just for an indoor training facility for boxers, runners, gymnasts, and even e-sports players. In Philly, the entire Parks and Rec budget is $83.4 million.

It seems clear, in other words, that if we want to level up on our youth sports, it’s going to take more than just what the city coffers have to offer. It’s time we all look elsewhere — lots of elsewheres — for creative solutions.

•

It was the night of the “Battle of the Beach” game — La Salle College High School versus Malvern Prep in Ocean City. Enon Eagles athletic director Greg K. Burris couldn’t make it to the Shore — he was running his own football practice in North Philly. But he streamed the game live, beaming the whole time. La Salle’s dramatic 42–35 victory was due in part to three Enon Eagles alumni who all scored touchdowns, as well as “a couple of guys on defense wreaking havoc.”

“I was sitting there with my chest puffed out,” Burris says.

The Eagles are a refreshing end run in the world of Philly youth sports, part of the 149-year-old Germantown-based Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church, which has more than 5,000 members at its two locations. The church’s athletic program is a little more than 20 years old — a model that ought to be studied, scaled, and replicated. The program includes baseball, basketball, football, soccer, track and field, cheerleading, martial arts, and tennis opportunities — all part of the “athletic ministry” at the church. Participating families (including non-Christians; the teams take all comers) aren’t obligated to attend services or be members, but there is Bible study offered after practices and games. “We are a church,” Burris says. “We don’t hide that.”

The 700-plus kids in the Eagles program play against other neighborhood programs, and Enon offers reasonable registration fees (they vary depending on the sport; in some cases there’s no fee), handles upkeep on the facilities they use — including a turf field — and mitigates equipment and travel costs through offerings and tithing from church members. Their programs run year-round and attract families from all over the city. Volunteer coaches direct the teams, and parents help out with day-to-day operations.

As the Eagles soar, there’s more hope — and more ideas — to be found, as the city does what it can, little by little. There’s Vare, of course, and other crucial rec center improvements in progress at Johnny Sample Recreation Center in Cobbs Creek Park, which will feature new indoor basketball courts and a pool. There’s also FDR Park, which will soon welcome a facilities bonanza, thanks to money from the city and state, grants from entities like the William Penn Foundation, and contributions from outside organizations like the Reinvestment Fund.

When, a few years back, the Fairmount Park Conservancy surveyed 3,000 South Philadelphians, they learned that more basketball courts ranked first on the collective wish list for FDR Park. Another priority was athletic fields. And so that’s what’s in the works (albeit the very slow works): 12 new multipurpose fields, a baseball/softball cloverleaf, and eight new courts. (Five multipurpose fields will debut in 2026, according to Conservancy chief operations and project officer Allison Schapker; they’ll be available via permits to teams and programs from all over the city.)

Inter Philly’s Robick is optimistic about what the FDR development means for kids sports. “It will be a crown jewel of the city,” he says. “It’s easy to get there. There will be cork pellets on the turf fields that are non-cancer-causing. And people can use it from 5 a.m. to 1 a.m. if they want to.”

Football at Vare

Another initiative worth getting excited about? The $36 million Alan Horwitz “Sixth Man” Center in Nicetown, home to the 10-year-old Philadelphia Youth Basketball enterprise. The place opened in the summer of 2024, the result of a $5 million gift from namesake Horwitz (founder of Campus Apartments and Sixers superfan) and then a multi-year campaign from the PYB that gathered a number of investors and contributors who bought commemorative bricks in the building for $250 each. A combination of that funding plus donations from private citizens and foundations, grants, city and state money, and revenue from renting the building to AAU basketball teams and other groups has brought the 100,000-square-foot facility to life.

Today, PYB offers athletic competition and training there, along with a variety of off-court enrichment programs for some 1,600 kids and teens. Previously, PYB held practices, games, and after-school activities at middle schools in North and Northwest Philadelphia. Now, the Horwitz Center is the hub, and the organization has expanded its reach to 24 middle schools, says PYB chief mission officer Ameen Akbar.

“Basketball is the carrot,” he says. “It’s how I grew up and a lot of us grew up in Philadelphia. That is the avenue we use to connect kids with quality coach-mentors and solid adults in the area. Then, we introduce them to the developmental programs.”

Like the Enon Eagles, PYB offers a good program and a great model. Like Vare and eventually like FDR, it offers a place to play that reflects the worth of our youth sports. Of our youth themselves. We could use many more.

In a city with a Chamber of Commerce that knows good and well the benefits of having families rooted and happy here; with the immense reach and vision of Comcast and Comcast Spectacor; with the talent and cash of the Sixers and the Flyers and the forthcoming WNBA team; with the heart and heft of two world-champion pro teams, each with its own stadium (and a new one maybe in the offing); and with our universities, rife with sports and with young talent itching for work experience, what other viable models of support might exist? How many rec centers could be adopted? How many more teams could get coaching help? Or lighting for their fields? Or new fencing? How many 10-year corporate commitments to paying for field upkeep or uniform donation or training programs for community members might make a difference to countless children and neighborhoods?

The World Cup is coming to town in a handful of months, with some $770 million in economic impact, reports suggest. How about taking a hefty sliver of the tax money coming in and using it to bolster Inter Philly and other soccer initiatives? Major League Baseball will likely throw a few million toward youth sports this summer when Philadelphia hosts the All-Star Game, as it did in 2025 in Atlanta. Now is the time to figure out how to find matching donors, how to use that money to roll into bigger public-private partnerships, how to invest in something more lasting than patching up our fields for a season. Now is the time to understand what is at stake in this moment, to proceed with intention. Ahead of the massive sports year that will be 2026 in Philadelphia, why not appoint a youth sports czar, Mayor Parker?

The overwhelming benefits of citywide youth sports programs and more facilities to host them — like Vare, like Marian Anderson — will help the next generations build a sturdier, safer, stronger urban fabric. It will also create that now, in real time. It will boost our neighborhoods. “We’ve seen the community embrace us,” the Sharks’ Mathis says. And obviously, as he notes, it also makes a difference to our young people, who have an outlet and a place they can claim — and come into — as their own. Something every kid deserves.

Published as “Leveling the Field” in the December 2025/January 2026 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

“You’re never going to get every call right, and you have to be willing to accept that going into it,” he added. “But you know the rules and apply the rules the best you can, you put yourself in the best position to make the calls, especially in basketball, and you call it the way you see it.

“You’re never going to get every call right, and you have to be willing to accept that going into it,” he added. “But you know the rules and apply the rules the best you can, you put yourself in the best position to make the calls, especially in basketball, and you call it the way you see it. In conjunction with teaching, Allen continued to officiate basketball in the winter and baseball in the spring and summer. He umpired a lot of men’s summer league softball games through the years and grew to love in particular working the games under the lights at Cadillac’s Lincoln Field.

In conjunction with teaching, Allen continued to officiate basketball in the winter and baseball in the spring and summer. He umpired a lot of men’s summer league softball games through the years and grew to love in particular working the games under the lights at Cadillac’s Lincoln Field.