Rec Sports

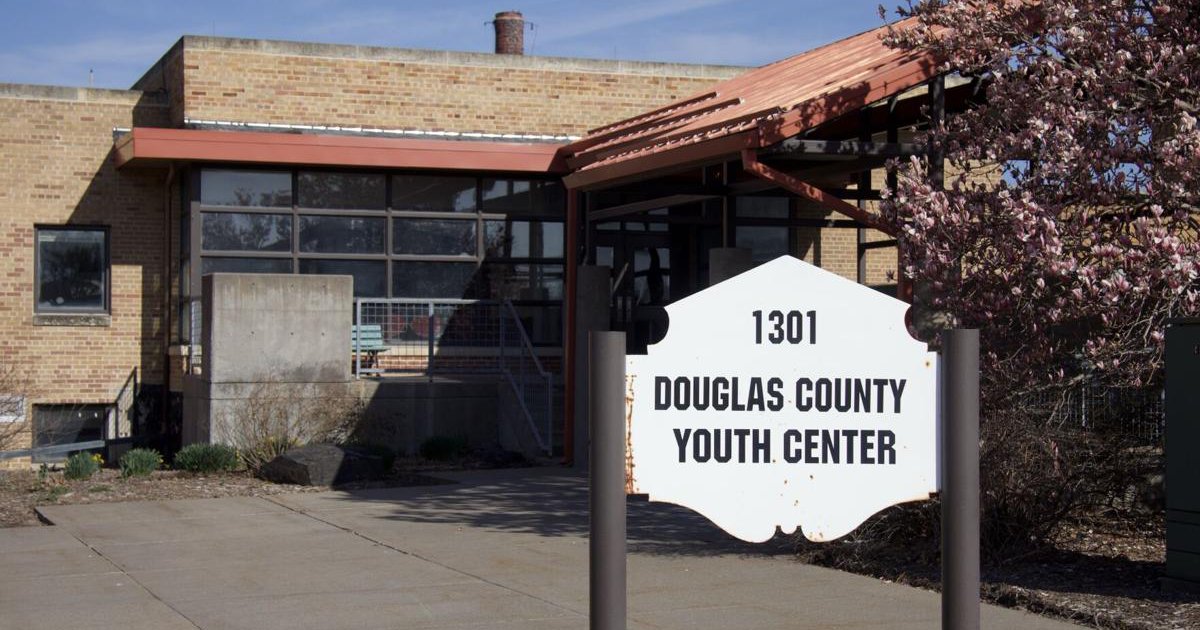

Youth say use of juvenile confinement breaks law

Douglas County leads statewide increase

Juvenile facilities began reporting quarterly room confinement data to the Nebraska Legislature after senators passed Legislative Bill 894 in 2016. Since then, the Office of Inspector General of Nebraska Child Welfare has compiled data in an annual report, which is provided to the Legislature. That four-person office investigates incidents and misconduct in the entire state’s child welfare and juvenile justice systems.

The 2023-24 facility data revealed “concerning trends” in room confinement use, according to the report. Compared to the previous year, there was a 110% increase in total confinement hours and a 48% increase in total confinement incidents.

“Based on the data alone, it appears that these increases are contrary to Nebraska law,” the report said.

Seven of the eight juvenile facilities in Nebraska reported increases in confinement hours, including the Douglas County Youth Center. It alone was responsible for 57% of the total 119,300 confinement hours, according to the report, meaning youth at the Omaha facility spent a combined total of nearly 8 years in confinement.

Douglas County is Nebraska’s largest county by population.

The center also holds youth in confinement for the longest of any Nebraska facilities, the 2023-24 report shows.

Douglas County Youth Center’s average incident time was 145 hours and 42 minutes, or roughly six days, which is the longest average in Douglas County’s history, dating back to 2016 when record keeping began.

‘Making it all worse’

The increases in confinement use raise alarm bells for youth advocates like Anahí Salazar, policy coordinator at the nonprofit Voices for Children. Salazar said the data leads her to believe that facilities aren’t following current law.

“If you’re using it as a timeout, then a young person doesn’t need to be in there for six hours,” Salazar said.

Facilities are also required to report the reason a youth is in confinement. In 2023-24, Douglas County reported that 221 room confinement incidents were used to address fighting; another 189 addressed assault or attempted assault.

Salazar said she hopes facilities are working to calm youth before putting them directly in confinement after engaging in aggressive behaviors.

Failing to speak with youth about their behavior while keeping them confined only increases the likelihood they’ll repeat the behavior, she said.

“If you’re not providing that for these young people…within, you know, an hour, two hours, three,” Salazar continued, “then I just think it’s making it all worse.”

The 17-year-old central Omahan, who said he was confined six times, said there aren’t many opportunities for youth to speak with staff about coming out of lockdown.

“We don’t really have much of a voice in it,” he said. “Whatever they say happens. There isn’t really nothing that we can say that’s going to change it.”

Woodard said that while his staff tries alternative methods to resolve issues with youth, confinement is sometimes necessary for safety – especially when violence stems from gang-related issues and conflicts that started outside of the facility.

“A lot of the violence that takes place in the Omaha community is generational,” Woodard said. “It comes from things that have happened years ago.”

If teens get into a conflict over a basketball game, staff can usually help them work it out through conversation, he said.

When a gang-affiliated teen in the facility sees someone they consider an enemy, Woodard said the teen is more determined to cause harm. In these cases, he said, talking things through or using positive rewards often isn’t enough to keep everyone safe.

“If a kid is really angry, they really don’t care about it,” Woodard said. “We can only give them so many bags of chips and positive reinforcement.”

‘Really big trigger’ for youth with mental health issues

Over 70% of youth in the U.S. juvenile justice system have mental health conditions, with 30% of those youth having severe conditions, according to The Council of State Governments Justice Center.

Monica Miles-Steffens, compliance coordinator at the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Juvenile Justice Institute, said it’s important that facilities recognize the psychological impact of confinement.

“Putting a kid in isolation can be really harmful,” Miles-Steffens said. “Especially young people who have mental health concerns.”

In 2024, the American Psychological Association formally opposed the use of “harmful individual isolation” in juvenile facilities and adopted 10 recommendations, several of which Nebraska has already incorporated into state law, such as documenting its use and using it in a time-limited manner.

Miles-Steffens said facility staff also need to recognize past experiences of youth, such as trauma during childhood.

“Some of these kids with crossover issues in child welfare, they were removed from their families because of very traumatic neglect and abuse situations where they might have been placed in isolation for extended periods of time,” Miles-Steffens said. “It can be a really big trigger for those kids in that trauma.”

System crossover is common. A 2021 study led by criminologist Denise Herz found that two-thirds of youth involved in Los Angeles County’s justice system had previously interacted with the child welfare system.

Tarika Daftary-Kapur, a researcher at Montclair State University in New Jersey, has focused her work on juvenile justice and adolescent decision making.

Research shows that confinement can have lasting mental harm on young people, she said.

“Solitary or room confinement for children, and even adults, for long, sustained periods of time can lead to depression, it can lead to anxiety,” Daftary-Kapur said. “Because they have higher levels of developmental vulnerability…they are at an even heightened risk of having these sorts of adverse reactions.”

Educational access limited

Nebraska law requires juveniles in confinement to have the same access to education as the general population.

Douglas County Youth Center’s daily schedule includes classes in the morning and afternoon, during which teachers instruct youth in person and through learning packets.

The central Omaha teen said teachers were his favorite staff.

“They’ll sit there and talk to you about anything,” he said.

During a 30-day period he spent on lockdown, he said he didn’t interact with teachers or fill out the daily packets, because he wasn’t allowed a pencil in his cell.

Christine Henningsen, associate director of Nebraska’s Center on Children, Families and the Law, previously worked as a public defender in Douglas County. She said staff at the Douglas County Youth Center have told her that youth in confinement aren’t allowed to leave their rooms for classes.

“If you’re in room confinement, what I was told is you’re not let out, but you can listen (to teachers) at the window,” Henningsen said. “And you could knock on the window and hold up a worksheet and try and get feedback from the teacher from the other side of your door.”

Douglas County Youth Center provides additional reading materials to youth through its library services, but the Bennington teen said the library is unavailable to youth while in lockdown.

“You got to just hope somebody will go get a book for you,” he said. “And then hope it can fit under the door.”

Each situation is handled individually, Woodard said. Teens who write on the walls or make weapons with pencils may get items taken away, he said.

“There’s way more factors than this just being simple,” Woodard said.

Family visits

The law also states that youth in confinement must have the same access to visits with legal guardians.

However, the Douglas County Youth Center’s website specifies that youth in “restrictive housing” are only allowed to have visits in the facility’s admissions area, and these visits may be restricted from an hour to 30 minutes due to “space availability.” Youth who are not in confinement receive two one-hour visits each week, according to the facility’s website.

The main visitation area, the North Omaha teen said, has multiple tables and vending machines, and multiple youth are able to have visits at a time. He said the admissions visit area is only large enough for one youth and two visitors at a time.

“In the other room, it’s like the cell,” the 16-year-old said.

Youth in confinement are strip-searched before a family visit, which the central Omaha teen said doesn’t occur with general population visits.

“A lot of kids would miss out on their visit, because they know they’re going to get strip-searched,” he said.

The Benson teen said strip searches are typically only used when youth first arrive at the facility. During his time in confinement, he said he passed up multiple visits with family to avoid going through the experience.

“Some people might not be comfortable with it,” he said. “There may be trauma behind it.”

The North Omaha teen said certain staff members made him feel especially uncomfortable during those searches.

“I don’t know if a strip search is supposed to go like that, but they just get to looking all at you and stuff,” he said.

Woodard said youth in confinement are strip-searched after visits because these visits happen in a room that is not supervised by staff, nor is the room monitored with a camera. Strip searches are necessary to prevent contraband from entering the facility, he said.

“We already have parents who are in regular visitation who are bringing in contraband,” Woodard said.

The Nebraska Crime Commission, a state government agency, defines a strip search as “an examination of a resident’s naked body for weapons, contraband, injuries or vermin infestations,” and the commission’s juvenile standards say all searches shall be the least intrusive type necessary for a facility’s safety. A pat search, with clothes on, should be the initial way to search youth, according to the juvenile standards.

Advocates: More oversight needed

Reflecting on her previous work as a public defender, Henningsen said she wasn’t fully aware of the prevalence of room confinement before the annual reports started in 2016.

“Looking back, I wish it was something I would have been regularly asking my clients about, but it was not anything that anyone even talked about,” Henningsen said.

Mandating the annual reports was a step in the right direction in holding facilities accountable to the law, she said.

“That, in and of itself, I think dramatically reduced the amount it was used, because they’re like, ‘Oh, somebody’s looking at it,’” Henningsen said.

While the inspector general for Nebraska’s adult prisons conducts regular in-person facility visits, the child welfare inspector general relies on self-reported facility data when creating the juvenile room confinement report.

“We don’t have the authority right now to go in and say, ‘When there was this confinement, what really happened?’ and make sure it was a safety and security reason,” said Jennifer Carter, the state’s inspector general for child welfare. “We’re just looking at what the facilities are self-reporting.”

Rec Sports

Interim President: AAL Has No Plans To Change Mission

The Acreage Athletic League has been around for more than three decades and will continue its youth sports mission with or without the support of the Indian Trail Improvement District, AAL Interim President Tim Opfer told the Town-Crier.

“Whether we do it at Acreage parks, we’re going to do it anyway,” Opfer said recently. “We’ll find a place to play… [but] I hope it doesn’t come to that.”

The ITID Board of Supervisors oversees the local park system in the Acreage/Loxahatchee area, including Acreage Community Park North and South.

“I think [Opfer] has good intentions,” ITID Supervisor Richard Vassalotti said. “I hope there’s a change in direction, but there are a lot of people who are very, very unhappy.”

For a number of years, the AAL held a service provider agreement with ITID, giving it near exclusive use of the parks. However, after months of controversy, the supervisors voted in February to extend to the AAL a one-year “nonprofit athletic user agreement,” giving its teams first priority for field space while making room for other organizations, such as the Breakthru Athletic League.

“I’m glad we’re at a place where, for the most part, everyone is fairly comfortable,” ITID President Elizabeth Accomando said at the time. “Residents and parents will no longer be coming to us. This separates us from that.”

Behind the scenes, though, tension simmered between coaches, parents, players and the executive board, which often was accused of incompetence and a lack of transparency.

Now, at least one sport — Acreage Adult Softball — served notice to the supervisors at a Dec. 10 meeting that it intends to break away from the AAL.

Acreage Adult Softball President Elizabeth McGoldrick told the supervisors that there is a “lack of structure on the executive board” and that the AAL “provides no support” to her 18-and-older co-ed league, despite keeping control over the league’s bank account.

Her softball league has “a great board, and we have it down to a science,” McGoldrick said later. “We kept reaching out to the [AAL] board, and we kept getting crickets.”

The softball league’s decision to separate from the AAL is not a surprise, Opfer said. “They’ve been wanting to do it for a long time,” he said.

The time is now, McGoldrick said. “We’re in the process of making the change,” she said.

That includes starting a spring schedule that will begin play in late January or early February to go along with the league’s usual fall schedule.

The AAL began in 1993 with a group of parents wanting to bring organized sports into the unincorporated, semi-rural enclave. With the guidance of the Acreage Landowners’ Association, the first AAL Executive Board of Directors was formed to oversee activities for some 200 young players, and the league incorporated in 1995.

Today, the AAL web site says that there are 2,000 registered players participating in tackle football, co-ed flag football, Acreage Elite flag and girls flag, baseball, basketball soccer and softball.

However, instability and in-fighting have plagued the AAL’s executive board in recent years. When Carlos Castillo was pressured to resign as AAL president in November 2022, Wendy Tirado, a board member since 2016, was named acting president and later elected to the position by the board.

Tirado resigned over the summer, and Opfer, the league’s technology specialist, stepped in to fill the void. Three executive board positions remain open.

In November, Ruben Paulo Tirado, a former coach at Seminole Ridge High School and with the AAL, was arrested on charges of lewd and lascivious battery and soliciting sexual conduct by an authority figure. Ruben Tirado, allegedly Wendy Tirado’s son, has pleaded not guilty.

The AAL “has hit a lot of speed bumps… and they hit a pretty big speed bump in November,” said ITID Supervisor Patricia Farrell, adding that she believed the arrest has had an impact across the district. “Parents are concerned.”

So are players, McGoldrick said. “It shouldn’t affect our [softball] league, but sadly it is. People see us as connected to the AAL.”

Opfer is quick to point out that the enhanced sexual offender notification system used by the league worked as it is supposed to.

“We were notified right away,” said Opfer, adding there is no indication of an issue related to Ruben Tirado’s time with the AAL, and ITID officials said there is no evidence of improper conduct on district property.

Still, it’s another jab to an organization that has taken its share of punches over the last few years, and it has put the supervisors back in the uncomfortable position of dealing with more AAL issues.

“We’ve spent so much time and energy on all this sports stuff,” Accomando said recently. “I know it’s important to a lot of people, but it shouldn’t be the focus of so many of our meetings… Giving permits for field space is all [the district] should be doing.”

Opfer said he understands that the AAL needs to make systemic changes, such as seeking more representation on the executive board from sports such as basketball, and delivering more transparency about the inner workings of the board. Part of that is an overhaul of the league’s “infrastructure” — it’s web site and e-mail communications.

More than that, Opfer said he hopes to rebuild the strained and sometimes broken relationships created when an AAL flag football faction broke away to form Breakthru in 2022. Breakthru has since become the AAL’s biggest rival for flag football talent.

Opfer said he’d like to see cross-league play or perhaps tournaments between AAL and Breakthru teams.

“I know there are still hard feelings on both sides,” said Opfer, but he noted that his daughter plays in the Breakthru league. “Both leagues have some challenges. It’s time we put our egos aside and build those relationships back.”

Rec Sports

Williams leading Lakeview wrestling through first year | News, Sports, Jobs

Staff file photo / Preston Byers

Lakeview head wrestling coach Ryan Williams celebrates a pinfall victory during the Bulldogs’ home meet vs. Leetonia and Austintown Fitch’s B team in Cortland on Dec. 17.

When Ryan Williams stepped down as the Liberty head wrestling coach in 2024, he admitted that it was not for a lack of passion for the sport, but rather a time commitment he could no longer make while raising young children.

A year later, things had changed somewhat.

“My wife finally gave me the green light,” Williams said. “She made me take that year off because of the kids, and she saw that I was miserable.”

His wife’s only condition for Williams to return to the sport, he said, was that it had to be close to their home in Cortland. So he got to work.

Lakeview, like many schools in the area, did not have a wrestling program, which Williams suggested should change. He said that he initially met with the principal and athletic director, who warned him that the district would not provide any funding to a team if he created one.

Undeterred, Williams agreed and quickly decided that he did not want to wait around as things worked their way up the chain of command.

“They said, ‘Yeah, well, then we’ll meet with the superintendent, see what kind of progress you make over the next couple months.’ I was impatient. I didn’t let it go a couple months. So I secured a mat and uniforms the same day I talked to the AD and principal,” Williams.

By mid-April, a little over a month after receiving the go-ahead from his wife, Williams got the meeting that he wanted.

“I just kept telling them to get me in front of the superintendent,” Williams said. “She was very hesitant at first, but I don’t think she fully realized at the very beginning that I wasn’t asking for money for coaches’ contracts; we’d completely fund it. She’s like, ‘Well, yeah, go ahead.’”

With the wrestling club and its donors covering bussing, uniforms and just about everything else, what Lakeview provided was its approval and a place to practice; Williams said they are currently in the high school cafeteria. They had been looking at a specific classroom to move into, he said, but that plan might already be no good.

“Since our match against Liberty, I’ve had nine new kids show up. So it just keeps growing, and now I’m starting to wonder, I don’t think the room is going to be big enough. We might have to stay in the cafeteria,” Williams said.

These are definitely good problems to have for the nascent wrestling club, which is sanctioned by the Ohio High School Athletic Association (OHSAA) but technically not one of the school’s varsity sports.

Williams said that he had initially considered starting at the youth level to build the Lakeview wrestling program from the foundation, but the buzz around the community, he said, made him decide to pull the trigger on starting youth, middle school and high school boys and girls teams all at once.

“So far, it hasn’t backfired,” Williams said.

When he started out, Williams hoped he could get about 50 kids to join the programs. But four months since the first fundraiser, 90 have come aboard, he said, with many from nearby Scrapyard Wrestling Club.

Williams credited the reach of social media, particularly Facebook, and the support of Lakeview head football coach Ron DeJulio Jr. for the rapid growth of wrestling in the area.

“That goes a long way,” Williams said. “Anytime the head football coach backs a wrestling program, it benefits both programs. … He realizes we’re a smaller school district and we have to share athletes.”

On Dec. 17, the Bulldogs hosted their first home meet vs. Leetonia and Austintown Fitch’s B team, two very different squads.

Fitch, one of the largest and best wrestling programs in the area, dominated the competition despite bringing none of their best talent. Leetonia, on the other hand, had fewer than a half-dozen wrestlers to compete with the expansive Lakeview and Fitch rosters.

Still, Williams said then that the experience was a good one, and that his wrestlers could see up close what they could potentially become with time. The meet also served as a valuable experience for those not on the mat, such as the scoreboard operators and fans in attendance, many of whom are new to the sport entirely.

“I guess the biggest difference is nobody here knows anything about it as far as what to expect on match day or tournament day,” Williams said. “So it’s kind of like my phone rings off the hook answering questions leading up to events. But there’s a ton of parent involvement.”

Williams’ ambition has not only been supported by those in the community, but Fitch head wrestling coach John Burd also made it clear that he hopes to see the Bulldogs and his friend succeed.

“They’re doing an excellent job building it from the ground up,” Burd said. “… Hats off to Ryan, he’s getting a lot of good people around him, getting support from their administration. I know their athletic department, principal, staff, all of them have been behind him, helping him and supporting him along the way.”

While many of the Bulldogs are effectively pups when it comes to wrestling, Williams said two of his wrestlers have been standouts so far this season.

“Aurora Hall, I have full confidence that she’s going to make a run to the podium at state,” Williams said. “Dustin Corbett, he’s got some prior experience from where he lived prior – he came from Greenville – but he hasn’t wrestled in four years. But he’s wrestling lights out.”

Either Hall or Corbett having success this season, especially in February and March, could prove to be massive for the Lakeview program as Williams tries to keep interest in his club high through the inevitable growing pains.

“[I want to] get them hooked, maintain the numbers, keep them excited,” Williams said. “It’s been challenging, you know, because you go into most matches expecting to lose, right? Everybody has way more experience than us, but they go out there and battle, and they’re trying to win and not just cowering down.

“They show up the next day. They’re excited. They want to learn where they can improve. This group of kids, especially, has been awesome.”

Rec Sports

Young entrepreneur marks milestone with donation to Angels for Animals | News, Sports, Jobs

Ellie Kaley, 7, shares some of the supplies she donated to Angels For Animals from her Ellie’s Glitter Lab proceeds. Kaley also donated a $100 check that will be doubled as part of a current campaign by one of Angels’ volunteers towards facility upgrades. (Photo by Stephanie Ujhelyi)

The Mahoning County-based non-profit is in midst of a campaign to upgrade celebrated marking her first six months in business with plenty of kittens.

While Ellie didn’t walk away Monday afternoon with a kitten, she and her mother Renee came to Angels’ headquarters with a $100 check, which will be matched as part of a current campaign, as well as a variety of supplies, ranging from paper towels and window cleaner as well as Temptations’ cat treats and peanut butter to be inserted in the dogs’ Kong toys.

While most kids that are Ellie’s age are playing video games and with fashion dolls, she started her business Ellie’s Glitter Lab in July and has spent the last six months selling glitter hair and face gel through the area at cheerleading competitions and craft shows.

With her mom acting as her business adviser, Ellie shared some of the things that she has used so far in 2025 about business, including selling its not as much about making money as it is making people happy.

Clockwise from left, Ellie Kaley visits with kitties in the Cat Tree Room of Angels For Animals on Monday after making a donation on behalf of her business, Ellie’s Glitter Lab, as mom Renee Kaley and Sherry Bankey, Angels’ feline manager, accompany her. (Photo by Stephanie Ujhelyi)

Early on Ellie had struck a deal with her parents that after six months that she could spend some of her money on a cause that she was passionate about.

Ellie explained that is where Angels For Animals had came into the picture. Years ago, the Kaley family had come to Canfield in search of a new furry friend after one of their dogs had passed.

They pondered adopting a cat named Winston, who shared the same name as their dearly departed. However, they quickly discovered a cat allergy made that an impossibility.

In addition to her regular favorites in her product line, Ellie’s introduction of specially themed lines like for Halloween and Christmas have proved popular, resulting in a lot of return customers as well as copycats.

She also does custom combinations based on school colors.

In addition to her Angels’ donation, Ellie has been able to spend some money on herself. While kittens and puppies are some of her favorite things, her bedroom also got a facelift that would be Elle Woods approved.

After her parents bought her a new loft bed and vanity, they upcycled it.

The decor, which is all pink and Ellie — not Elle — approved is all courtesy of her money. She even included a reading corner and makeup spot in her room.

Her commitment to her business seems to holding strong, as mom says that Ellie’s Glitter Lab looks to reinvest in the company and possibly expand to include a new line of hair bows.

For information on Ellie’s Glitter Lab, visit her Facebook page or call 330-550-4741.

Rec Sports

‘Christmas tradition’ welcomes more than 170 area children | News, Sports, Jobs

PHOTO BY RUBY F. MCALLISTER —

Rev. Mark Keefer of Traer United Methodist Church, right, visits with a youngster during Kids Shopping Day on Saturday, Dec. 13, at Peace Church in Gladbrook.

GLADBROOK — For the second year running, Gladbrook’s beloved Kids Shopping Day took place amid a significant winter storm. But not even intense snowfall and cold temperatures could stop more than 170 children from attending (with their caregivers) the 13th annual event held on Saturday, Dec. 13, 2025, at Peace United Church of Christ in order to pick out gifts for their loved ones this Christmas season.

While attendance (171) this year was down slightly from years past, organizer Jeanne Paustian, who chairs Kids Shopping Day as a member of the Gladbrook American Legion Auxiliary Children & Youth Committee, said everything went well.

“I was happy so many (still) came. But I know if we have it, parents or grandparents are going to get them here.”

Kids Shopping Day has grown tremendously since it first began back in 2011 but still manages to remain true to the original intent – allowing children to more fully experience the joy that caring for others brings. The idea behind that very first Kids Shopping Day originated with now-retired Gladbrook kindergarten teacher Becky Fish, Paustian said.

“She came and asked me one day if I thought Gladbrook would support a Christmas store where kids could shop for their loved ones – no parent help and at no cost. And I said, well, I think we could do that. It was all Becky’s idea.”

In the early years, the event was held at the Gladbrook Memorial Building before quickly outgrowing the space. Today, Kids Shopping Day takes place over practically the entire two floors of Peace Church, including in the sanctuary where caregivers wait for their children as they “shop” downstairs. Without parental help, it requires an army of volunteers to orchestrate the event each year.

“We have a lot of different volunteers to help the children, including high school students – the little ones love going with them to shop. It takes about 82 people to make it all work,” Paustian said.

In addition to members of the Gladbrook Legion Auxiliary, Paustian receives volunteers and/or donations from almost all the area churches and organizations, including the Gladbrook Corn Carnival Corp., the Gladbrook Commercial Club, the Gladbrook Women’s Club, the Gladbrook Lions Club, the Legion, and many more.

“We wouldn’t stay afloat if we didn’t have all the organizations that supply volunteers and financial donations.”

It also takes roughly $3,500 a year to finance the massive endeavor despite about 75% of the items being donated outright. Cash donations are used to shore up tables.

“We always have to beef up toys and the men’s gifts. We [receive donations] all year long. As soon as Christmas is over, we’ll see stuff start coming in the door again.”

Following the shopping day, many of the leftover items are taken to Westbrook Acres for residents to shop for their own loved ones and for themselves, Paustian said.

“We’ll also take a few things that we know they like – such as puzzles – to Independent Living. We also make a donation to Trinkets & Togs [Thrift Store in Grundy Center].”

Trinket & Togs is part of the non-profit agency The Larrabee Center. All proceeds from Trinkets & Togs sales support services for persons with disabilities and the elderly.

Kids Shopping Day: 2025

Last Saturday, Dec. 13, as snow piled up on the sidewalk outside Peace Church’s south entrance, children were lined up down the street well ahead of Kids Shopping Day’s 9 a.m. start which kicked off with Paustian unlocking the church’s double doors. Once inside, attendees were greeted at the check-in table by volunteers Sherri Denbow and Becky Fevold who handed out gift lists and pencils.

After checking in, children proceeded upstairs to the sanctuary to deposit their coats (and their caregivers) before filling out their gift list with the names of family members for whom they would like to “shop.” Once their list was completed, they moved to the gift tag tables which were strewn with 100s of beautiful tags handmade by volunteers using discarded and/or past holiday cards.

From there, children ventured downstairs for the main event – shopping in the Christmas Store. At the entrance to the store’s large room, children were given a clipboard for their list plus a red or blue shopping basket. Preschoolers and kindergarteners received assistance from a volunteer as they perused the many tables. Once finished, children moved on to the wrapping stations – situated on the room’s periphery – where their selections were expertly prepared for gifting. They were then zoomed back upstairs (with their gifts) by elevator to a room located behind the chancel for a quick chat with the “People of Bethlehem.” This year’s cast featured Rev. Gideon Gallo of Gladbrook United Methodist Church, Rev. Mark Keefer of Traer United Methodist Church, Kay Lowry, Sue Storjohann, and Sierra Wiebensohn.

“Children can’t shop for themselves [at Kids Shopping Day], so they receive a nativity Christmas card and a nativity ornament (from the People of Bethlehem). They also tell them about the reason for the season,” Paustian explained.

Then it was time to find their caregivers in the sanctuary – or have a committee volunteer make a phone call – and head home with their bounty of carefully-curated gifts. This is the part Paustian said she loves the most as she hears about it later from parents and grandparents following the event.

“It’s really sweet – how they put them under their trees. They might rearrange them under the tree 100 times. They’re just so proud of their gifts. … It (really does) make you cry. I helped one little girl (on Saturday), she didn’t say one word to me. But she was so proud.”

And while the event takes place in the heart of Gladbrook, Paustian said children from far beyond the local community attend. On Saturday, there were children present from throughout Tama County as well as Reinbeck – including Gladbrook-Reinbeck Superintendent Caleb Bonjour’s children – and even Marshalltown.

But no matter how big it gets, Paustian said the committee has no plans to stop.

“It is a Gladbrook Christmas tradition that we plan to continue for years to come.”

Mark your calendars now – and hope for better weather! – Gladbrook’s 14th annual Kids Shopping Day is set for Saturday, Dec. 12, 2026.

M E R R Y C H R I S T M A S !

Rec Sports

Arrest made in Petaluma vandalism of former Harlem Globetrotter’s vehicle

A 20-year-old Petaluma man has been arrested in connection with the racist vandalism left on the vehicle belonging to a well-known local youth basketball coach and former Harlem Globetrotter, police said.

The suspect, Corey Newman, was linked to the vandalism through surveillance video, police said. He was arrested Wednesday during a traffic stop and taken into custody without incident.

He was booked into Sonoma County jail on suspicion of vandalism for defacing property and commission of a hate crime, police said.

The arrest marks a breakthrough in an incident that drew widespread condemnation after the coach, William Bullard, who is Black, posted on social media about the vandalism of his vehicle, which included racist slurs and swastikas scrawled in the dust on his SUV.

He also shared his account with The Press Democrat.

The vehicle was parked in a downtown Petaluma garage near Bullard’s apartment from Dec. 1 through Dec. 9, and was defaced at some point during that time.

Bullard, who noted the garage surveillance cameras in his social media posts about the incident, contacted police.

After reviewing more than a week of surveillance footage, officers identified Newman as the person believed responsible for the vandalism.

Bullard, who has lived in Petaluma for about five years, said the vandalism left him concerned about his safety.

“It is tough to deal with being a minority here in Sonoma County, where it is 1-2% Black,” Bullard previously told The Press Democrat. “With my impact within the community, to walk outside to your car and see that is really tough.”

Police, in their press release on the arrest, noted the media coverage and attention the attack had drawn through social media.

The department said it takes all hate-related incidents seriously and remains committed to thorough and impartial investigations, noting that crimes motivated by bias affect not only those directly targeted but the broader community.

You can reach Staff Writer Isabel Beer at isabel.beer@pressdemocrat.com. On Twitter @IsabelSongbeer

Rec Sports

Area basketball teams clash at Lewiston Auto Holiday Classic

WINONA, Minn. (KTTC) – In the wake of Christmas day, area basketball teams took their talents to Winona State University for the Lewiston Auto Holiday Basketball. The annual tournament features 27 games over four days of basketball. Day one was Friday.

Results from Day One:

- Chatfield beats Arcadia (WI), 59-57 (Girls Basketball)

- Chatfield beats Richland Center (WI), 58-41 (Boys Basketball) *

- Lake City beats Waseca, 60-24 (Girls Basketball) *

- Cotter beats Lake City, 81-74 (Boys Basketball) *

- Goodhue beats Winona, 88-72 (Boys Basketball)

All games are in McCown Gymnasium. The tournament continues tomorrow.

* = Watch highlights above

Find stories like this and more, in our apps.

Copyright 2025 KTTC. All rights reserved.

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoSoundGear Named Entitlement Sponsor of Spears CARS Tour Southwest Opener

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoDonny Schatz finds new home for 2026, inks full-time deal with CJB Motorsports – InForum

-

Rec Sports3 weeks ago

Rec Sports3 weeks agoDavid Blitzer, Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoRick Ware Racing switching to Chevrolet for 2026

-

NIL2 weeks ago

NIL2 weeks agoDeSantis Talks College Football, Calls for Reforms to NIL and Transfer Portal · The Floridian

-

Sports2 weeks ago

Sports2 weeks ago#11 Volleyball Practices, Then Meets Media Prior to #2 Kentucky Match

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoWearable Gaming Accessories Market Growth Outlook

-

Sports3 weeks ago

Sports3 weeks agoWomen’s track and field athletes win three events at Utica Holiday Classic

-

Motorsports2 weeks ago

Motorsports2 weeks agoSunoco to sponsor No. 8 Ganassi Honda IndyCar in multi-year deal

-

Motorsports3 weeks ago

Motorsports3 weeks agoNASCAR owes $364.7M to teams in antitrust case